This review is adapted from one that first appeared in the Times Literary Supplement of 19 July 2024 as part of a review article entitled "Burning Decks" (p.20). The author has reorganised and formatted it for the Victorian Web, adding extra details, page numbers, illustrations, and links to related material.

rigid Allen's joint biography explores the lives and achievements of a brother and sister at the very heart of Whig and colonial politics in the mid- to late-Victorian period. George Eden, the second Lord Auckland (1784–1849), and his sister Emily (1797–1869), embarked for India in 1835. George, who had inherited his peerage in 1814, served as Governor-General of the country until 1842, with Emily as his devoted companion. His term was marred by his share of the responsibility for the First Afghan War, and its bloody aftermath. Emily, whose Portraits of the Princes & People of India was published in 1844, and who later published her informal descriptions of life in the Governor-General's camp, and during stops at Simla and in the Punjab, in Up the Country: Letters to her sister from the Upper Provinces of India (1866), has been no less immune to the barbs of postcolonial critics. But both emerge from Allen's thoughtful and unprejudiced scrutiny as being far from stereotypical representatives of their era, their interwoven stories giving new insights in some of its most controversial aspects.

Sibling affection, for instance, which is apt to raise eyebrows now, was by no means unusual for the time. Yet Emily and George's arrangement was still quite unconventional. For men of George's class, advantageous matches provided funds and influence, as well as the prospect of continuing the family: "Few members of the House of Lords were bachelors; even the homosexuals among them usually married" (49). For women, societal pressure was, if anything, greater. Indeed, like her brother, Emily had her opportunities, and was disappointed when her promising relationship with Lord Melbourne failed. On the positive side, by keeping his sister at his side, the basically rather shy George gained the support of someone perfectly attuned to his needs, while Emily, for her part, avoided the potentially bumpy ride of marriage — when, as she puts in her novel, The Semi-Attached Couple, "two people as about as unlike to each other in habits, dispositions, and sentiments, as they could well be" had to forge a life together (283). Retaining a degree of freedom that might otherwise have been curtailed, she also gained much from her role: at home, she moved in political circles during the period when the Whigs were powerful, and, while acting as her brother’s First Lady in Calcutta and Simla, as Kolkata and Shimla were then known, she was embedded in the high-ranking colonial world of the period, and had a much more stimulating life than most women could hope to experience. This privileged and adventurous period gave her the material for her two non-fiction books.

However, there were challenges. Notable among the events during George's tenure as Governor-General was the First Afghan War of 1839. An able administrator, he had expected to exert his powers in India benevolently. And indeed he won acclaim on the domestic front with, for example, his “tactful” education policy (123), which avoided quashing the study of vernacular languages. But in 1838, Emily wrote to Lord Minto, former Governor-General of Bengal and the siblings’ cousin, asking if he knew that “poor dear peaceful George had gone to war — rather an inconsistency in his character” (165). Her brother had acceded to the idea, which had been gradually gathering momentum, that reinstalling the deposed but reportedly “useful” Shah Shuja in Kabul would protect British interests (162). At first, the plan seemed to have worked, and he was created Earl of Auckland after a major British victory at Ghazni (195). But with hindsight, it is deeply ironic to read Palmerston's remark that "[t]his glorious success of Auckland's in Afghanistan will cow all Asia and make everything more easy for us" (qtd. p. 195). For, early in 1842, when the British forces retreated from Kabul, they were slaughtered wholesale. Lady Butler’s well-known and unbearably poignant painting, The Remnants of an Army (1879), shows how the episode was seared into the national consciousness: it depicts a solitary, exhausted survivor, an army surgeon, entering the border town of Jalalabad on his equally battered mount.

Lady Butler’s The Remnants of an Army (1879), evoking the disastrous repercussions of the First Afghan War.

Both siblings were devastated. George in particular was hugely distressed at the time. Yet he showed great strength of character later, when, to quote the political diarist Charles Greville, he maintained a “very temperate, dignified and becoming” stance during the debates about the débacle in parliament (228). An official enquiry was averted. Looking back, he continued to be even-handed and temperate, praising the sepoys in another debate for their later service in China, when he was involved in raising troops for the First Opium War — not his own war, as Allen carefully points out at the beginning of Chapter 12, but Palmerston's. On this occasion, Queen Victoria was "very much affected" by his sympathy for the men (226). He comes out of Allen's account well: his subsequent rehabilitation was clearly less partial than his critics have claimed. In particular, he worked hard in his remaining years after being reappointed First Lord of the Admiralty – not at all a sinecure, as Allen also makes a point of explaining.

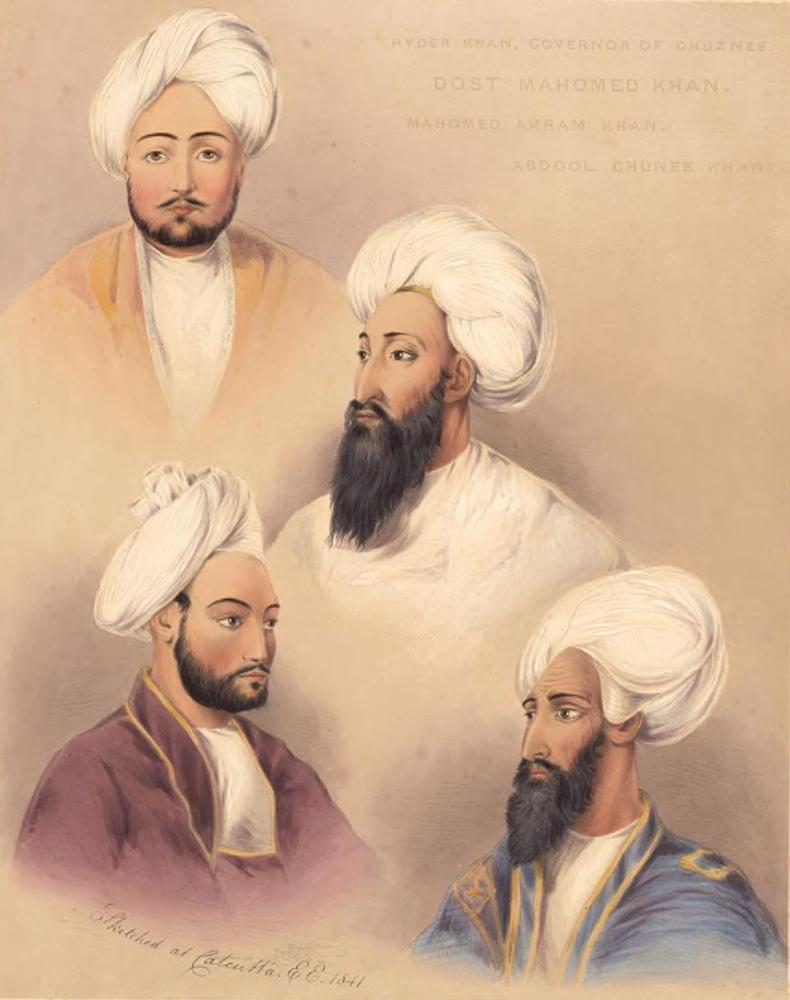

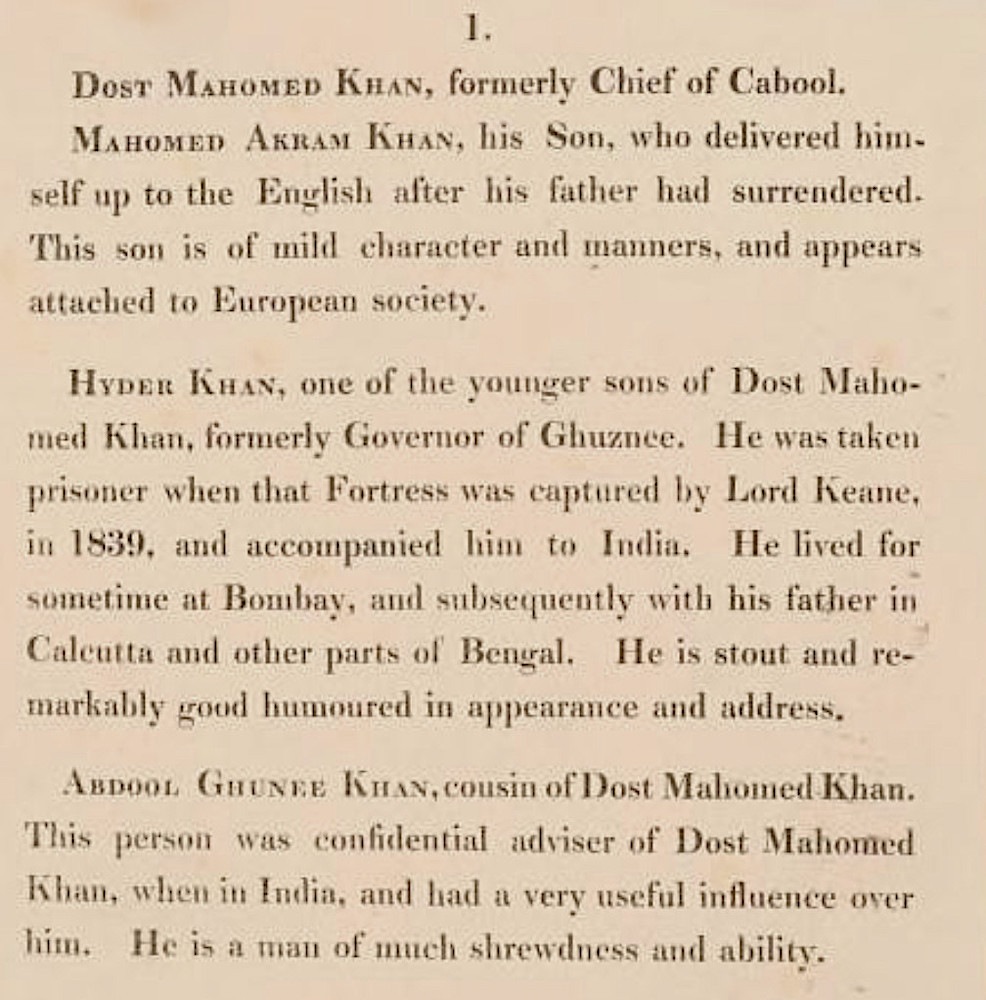

An earlier postscript to the events in Ghazni, bizarre rather than ironic, was the visit of Dost Muhammad Khan, the Afghan leader who had been ousted, to Government House in Calcutta. He attended a ball in celebration of Queen Victoria’s birthday, and played chess with Emily. The deposed leader and his sons duly featured in Emily’s Portraits of the Princes & People of India. The Amir's own wish to engage with the British, as well as his personable appearance and, as Emily noted herself, his "kingly" manner, help to explain this "entirely civilised arrangement" (213) whereby a leader forcibly removed from power by the British, and still technically their prisoner, enjoyed their hospitality. There seems little sense of condescension here, although the suggestion that a Jewish appearance ran in his family has been taken to imply an anti-Semitism which appears more obviously in the portrayal of Baron and Baroness Sampson in Emily's published novel of 1859, The Semi-Detached House.

Dost Muhammad Khan and his sons, and accompanying text, from Eden's Portraits of the Princes and People of India, p. 13.

If the description of the Governor-General's hospitality on this occasion betrays some racial and religious prejudice, that would hardly be surprising, in view of widely shared contemporary attitudes. But in one important respect, Emily came in for criticism from her contemporaries themselves. The political diarist Charles Greville called her intelligent but “wrong-headed" (226) implying that she had influenced her brother’s decision-making in the matter of the Afghan War, rather than simply stood by him — which is not entirely unlikely. More recently, she has also been taken to task for her colonialist attitudes. Yet it is worth noting that she was far from enamoured with her own fellow countrywomen in Calcutta, and, on the other hand, was “touched by the spirit of lost Mughal splendour” in Delhi (156). Allen finds that "Emily lost much of her insularity during the two years and four months of the tour" of the North Western Provinces and Punjab (155), and that goes in her favour as well, and suggests that she too deserves a new and fairer appraisal.

Emily's novels, issued together by Virago,

available to borrow on the Internet Archive.

Emily's keen eye as a social commentator is confirmed in the witty, entertaining and very English novels that she published after her return to England. Appearing in 1859, The Semi-Detached House popularized a “sparklingly new” name for the pairs of homes then appearing on the market. Florence Nightingale read it with pleasure, and Florence's close friend, the politician Sidney Herbert, who had been instrumental in her dispatch to Scutari during the Crimean War, claimed it had “become a sort of byword in London, and that if anybody talked of taking a house, the answer was, Semi-detached, of course” (qtd. p. 246). Emily’s next novel, The Semi-Attached Couple (1860), was actually an earlier manuscript dusted off and marketed under a title that capitalized on her recent success. Although less skilfully plotted, it has also kept its appeal, and both books are still in print – as indeed is Up the Country. On one level, the novels are simply society romances, leading from courtship to marriage and some way beyond. But there is a good deal of insight, too, into women's frustrations. Notable among these are the dilemmas of Baron Sampson's niece and ward Rachel, in The Semi-Detached House. Rachel is a complex character, far from stereotypically Jewish, and portrayed with sympathy and understanding. The dialogue itself can be positively (pre-)Wildean: "one never hears anything new until it is old," says Lady Portmore in The Semi-Attached Couple (93). It is also far less dated than one might expect. In the same novel, for instance, with its lively scenes of raucous electioneering, Ernest Beaufort declares that there is a "screw loose" with the opposing Douglas family (212), and the phrase is bandied about several times in the novel.

The spark had not faded, then, nor had Emily's world narrowed precipitously, even after her brother’s death in 1849. At the beginning of the 1850s, fleeing from the vicinity of the Great Exhibition in Kensington to the quieter and more salubrious air of Broadstairs, she had witnessed Dickens on his walks from the Fort House, making "theatrical gesticulations" (236), and become friendly with the Gladstones. But even before George's death, ten years before she published The Semi-Detached House, she had been a chronic invalid, subject to painful spasms from which only the newly discovered chloroform could relieve her. Once bereft of George and her sister Fanny she was attended by an unmarried niece, the Hon. Eleanor (Lena) Eden, daughter of her brother Robert, the third Baron Auckland, whose novel-writing may well have inspired her own renewed efforts in that direction. Her health deteriorated further, and the end came in her early seventies, in the summer of 1869.

Allen bewails the unavailability of the papers from which Violet Dickinson selected Miss Eden’s Letters in 1919, but she has had access to other rich archival resources, allowing her to write revealingly on both the siblings’ involvement in complex public issues. That Emily's published work can all be consulted on the Internet Archive is good news for readers whose curiosity is piqued by this thoughtful, scrupulously researched and rewardingly immersive biography.

Links to Related Material

- Prospects of India: Emily Eden and her brother Lord Auckland, 1830-35

- "British interference" in Afghanistan and the disasters of 1842

- “An indelible stigma of disgrace”: The Guns of Kabul

- The Afghan Church in Mumbai and the Guild of the Holy Standard

Bibliography

Allen, Brigid. George and Emily Eden: Pride, Privilege, the Empire and the Whigs. Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 2024. xiii + 305 pp. Hbk: £50.00; pbk: £25.00; also available as an ebook. ISBN 978-0718897451.

Eden, Emily. Portraits of the Princes & People of India, drawn on the stone by L. Dickinson. J. Dickinson & Son, 1844. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Caroline Simpson Library, Caroline Simpson Collection, Museums of History NSW. Web. 7 January 2025.

_____. The Semi-Attached Couple & The Semi-Detached House, with an introduction by Valerie Grosvenor Myer. New York: Dial Press, 1982.

Created 8 January 2025