r Pooter, although little known to the world at large, has entered the language in England. There the word conjures up a conventional, priggish, strait-laced, lower middle class white collar worker living in a semi-detached house in the suburbs with lace curtains and gnomes in the garden. The name itself is inspired, summoning up an image of a pooterish man by its sound alone.

r Pooter, although little known to the world at large, has entered the language in England. There the word conjures up a conventional, priggish, strait-laced, lower middle class white collar worker living in a semi-detached house in the suburbs with lace curtains and gnomes in the garden. The name itself is inspired, summoning up an image of a pooterish man by its sound alone.

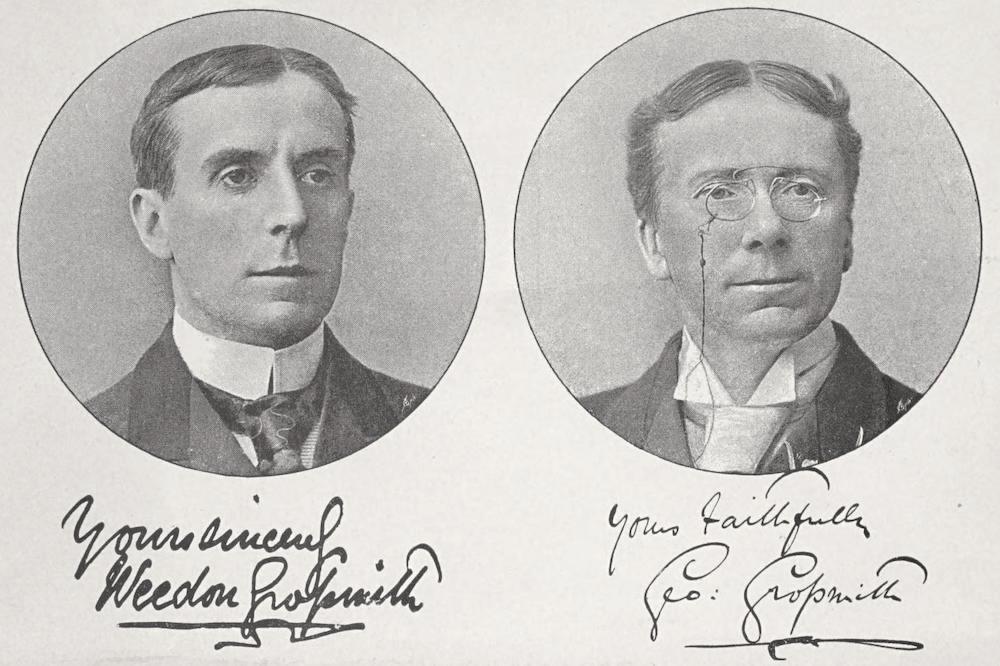

The Diary of a Nobody, in which Mr Pooter is the hero, was never meant to be a book; it was a weekly serial in Punch written over the course of a year from May to May, 1888-9. The book, which was published in 1892, is essentially the same as the magazine but with seven extra chapters. It's accredited to two authors, George and Weedon Grossmith. Weedon may have had no hand in the writing, but the illustrations are his.

Portraits of the Grossmiths as the frontispiece to The Diary of a Nobody. [Click on all the images to enlarge them.]

George was born in 1847 and began his working life reporting the goings-on in the Magistrates' Court in Bow Street (now closed but in its heyday famous for the Bow Street Runners, thief-takers before the advent of Sir Robert Peel's police force.) For eleven years he was one of Gilbert and Sullivan's principal singers. He left D'Oyly Carte in 1889 to take his own solo show on tour: he was like a one-man cabaret—songs, sketches, jokes, impersonations. He wrote most of his own material and on his first solo tour in England earned ten thousand pounds. This was followed by five tours of the United States which paid even more. He was also a fine pianist who composed music for several light operas. He died in 1913.

Weedon, seven years younger, trained as a painter both in the Slade and Royal Academy. For a time he painted portraits in a studio in Fitzrovia, the bohemian quarter bounded by Euston Road, Tottenham Court Road and (just about) Oxford Street. But, since he was none too good a painter, he also turned to the stage, as actor, producer, set designer and playwright. He was manager of Terry's Theatre until 1917, two years before he died. His illustrations capture the essential natures of some of the characters even better than his brother's words.

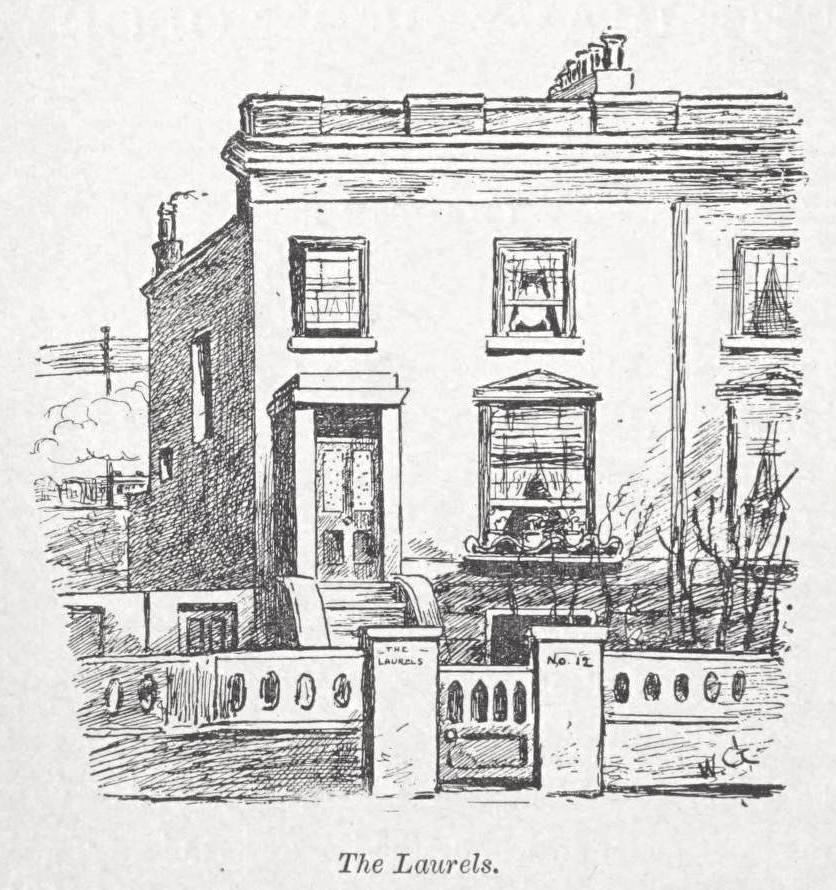

The book is governed entirely by its origin as a weekly serial in a satirical magazine. It is episodic, to be begin with — characters are introduced and never developed, while most of them are one dimensional ciphers. Only Charles Pooter is at all rounded. He is a middle-aged Head Clerk in a City office who, as the book opens, has just moved into in a rented house in the newly developed but unfashionable suburb of Holloway. (The Laurels, Brickfield Terrace, backs on to the railway where the vibration of the trains has cracked the garden wall.) The book relates his mishaps, his jokes, the rudeness of his friends, his daily domesticity, but also takes pot shots at some of the fads of the day — bicycling, spiritualism, the Aesthetic movement, child rearing, and even the fashion for publishing diaries.

"The Laurels" (6).

But there is a plot of sorts. Pooter and his wife, Carrie, have a son called Lupin. He is twenty. This is important because the age of majority was then twenty-one; Lupin, therefore, is a minor and still the legal responsibility of his father. But he is also wilful, wayward, reckless, money-grubbing, unscrupulous, and out of control but, it turns out, with head for business. We first meet him four months into the Diary; he has been fired ('given the chuck,' in his words) from a Bank in Lancashire. He gets involved with a troupe of amateur actors and becomes engaged to, and is jilted by, one of them — a brassy singer of twenty-eight who can't sing in tune and has a loafer for a brother (and a father who bars Lupin from his house because of his insolence). Pooter finds Lupin a job with a semi-crooked stock broker and then, when he absconds, in his own firm. This is where the Punch serial ended: Pooter has achieved his life's ambition — to have his son work alongside him in the same office and travel each morning in the same bus.

In the extra chapters, Lupin is fired again for treacherously helping the company's most important client when he withdraws his business. Lupin gets a better job. Meanwhile, Pooter's company is in financial trouble until a rich American, like a deus ex machina, saves the day. The news is broken to Pooter by Hardfur Huttle, an intellectual American journalist, on the 4th of July. Pooter has been instrumental in this change of fortune and his boss, Mr Perkupp, in gratitude buys the freehold of the house in Holloway and presents it to him. The book ends with a letter from Lupin: he is engaged to the rich brash thirty-something daughter of a hatter. Lupin is maturing.

Orwell said the ending — the last seven chapters — doesn't ring true, and it doesn't. The reason, he thought, was because of a Victorian desire for a happy ending. More cynically we can ask if George Grossmith already had an eye on those tours of the US. (Not that it would have done much good: the book was a 'sleeper' which didn't take off until 1910.) There might, however, be an even better explanation which we'll come back to later.

Much of the humour is about mishaps. Things always go wrong for Pooter. On their way to the Lord Mayor's Ball, the greengrocer's boy hands him blocks of coal and cabbages. The coal ruins his shirt; he slips on the cabbage and tears his trousers. At the Ball he slips and crashes to the dance floor taking Carrie with him. An overweight ironmonger cadges a lift home, doesn't offer to pay, and incenses Carrie by his insensitivity (he rips her skirt and treads on a borrowed fan made from the feathers of an extinct bird). Pooter upsets her as well by smoking without asking her permission.

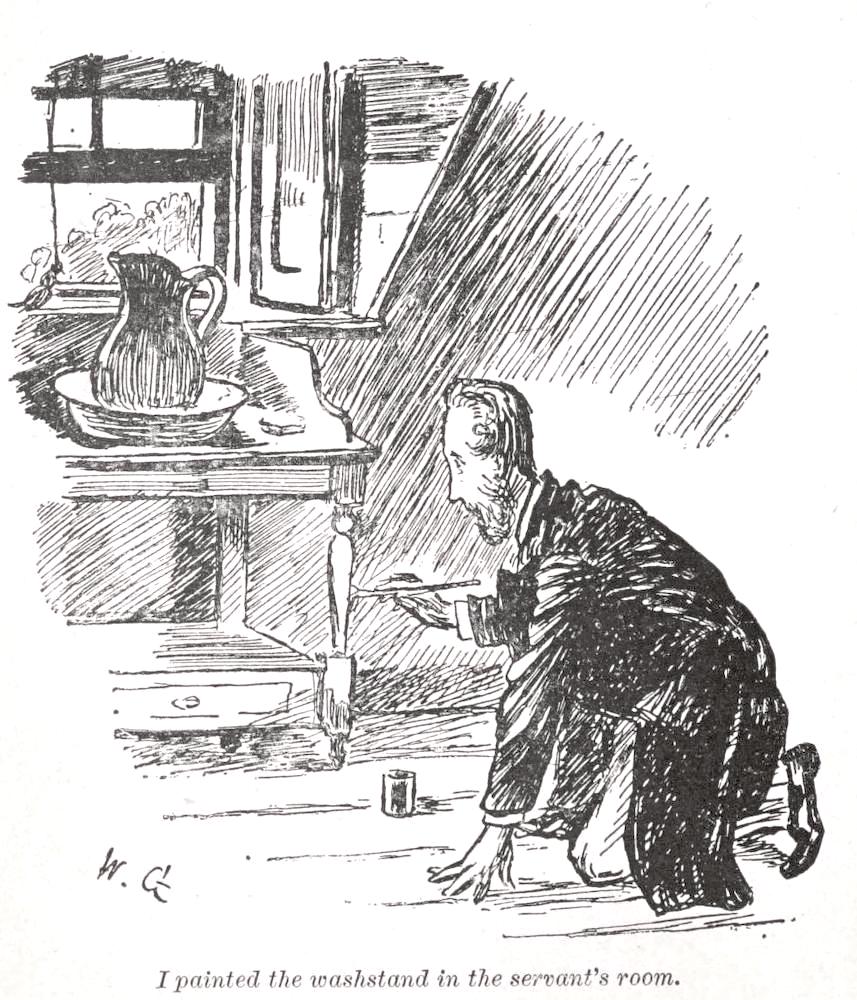

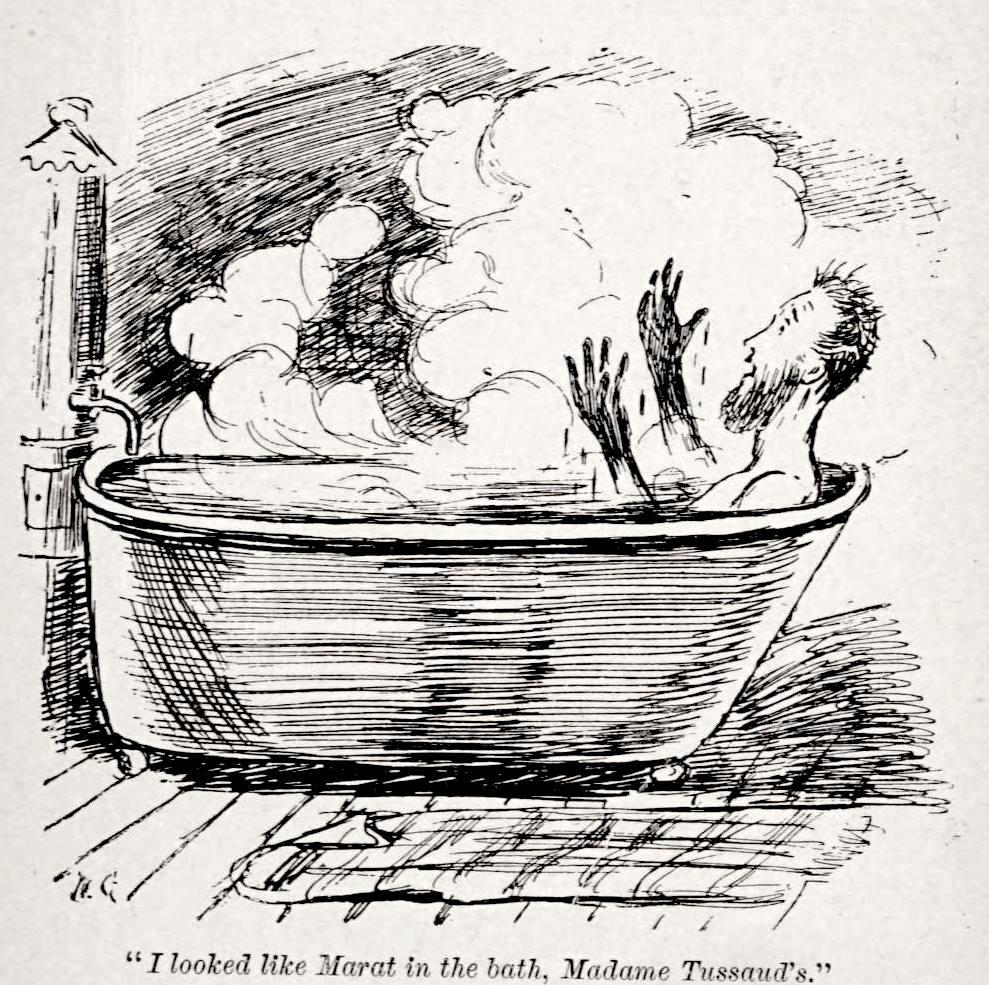

Another incident is illustrated by Weedon. In one drawing we see Pooter on his knees in a frock coat painting the washstand in Sarah, the maid's, bedroom with red enamel. In the next picture we see him in the bath tub holding up his stained hands in terror. He's also painted the tub: the red paint runs: he thinks he's severed an artery. He likens himself to Marat in Madame Tussaud's. (Victorian humour, we have to admit, can be a bit grisly.)

Left: Pooter painting the washstand in the servant's room (32). Right: Pooter in the blood-red bath (36).

Other episodes can come and go quickly. Modern child rearing comes in for mockery in a single issue. Carrie's old school friend has a son called Percy, perhaps the most appalling child in all of English literature. Percy kicks Pooter's shins, slaps Carrie's face, bounces a gentleman's watch like a ball, and accuses another of not washing. When Pooter remonstrates with his mother he is sharply reminded that Lupin is no great success either. Weedon, it is said, scoured every photographer's shop on Euston Road for a child ugly enough to copy. Percy, by the way, must be only four or five as he is still in frocks, as was the Victorian fashion.

Percy in his frock, looking sullen (211).

We hear about the bicycling craze in January, ten months after the start of the book. Pooter's friend Cummings has been laid up for three weeks: his doctor despaired of his life but nobody visited even though his illness was reported in Bicycle News. In April he is absent again, having fallen down stairs. Again, nobody visited even though the story broke, once again, in Bicycle News. Finally in July, after another absence, he brings Bicycle News with him. Mr. 'Long' Cummings —that favourite old roadster (we read) — was tipped off his tricycle by a boy in Rye Lane who threw a stick between the spokes of a back wheel. Then come the puns — 'fortunately there was more wheel than woe.'

Pooter has a real sense of humour, and so does Carrie, although their taste is entirely for puns or farce. Pooter's sallies — which surprise and delight him — can have the pair of them rolling around with uncontrollable laughter for hours. Pooter's two friends, for example, are called Cummings and Gowing (which seems to be pronounced go-ing).

'A very extraordinary thing has struck me . . . Doesn't it seem odd that Gowing's always coming and Cummings always going?' Carrie . . . went into fits of laughter, and as for myself, I fairly doubled up in my chair till it cracked beneath. I think this was one of the best jokes I have ever made.'

(It was: not one of the best — the best. The others (and there are several) are even worse.)

'Carrie brought down some of my shirts and advised me to take them to Trillip's round the corner. She said: "The fronts and cuffs are much frayed." I said without a moment's hesitation: "I'm frayed they are." Lor! how we roared. I thought we should never stop laughing.'

Lupin comes downstairs on the morning after a party.

'Hulloh! Guv,' he says, 'what priced head have you this morning?' I told him he might as well speak to me in Dutch. He added: 'When I woke this morning, my head was as big as Baldwin's balloon.' On the spur of the moment I said the cleverest think I have ever said; viz.: 'Perhaps that accounts for the para-shooting pains.' We all three roared.

Carrie is not always amused. On one occasion in their first Spring, Pooter is planting border flowers in their little garden. He calls Carrie away from her chores to listen to his latest outburst of wit. 'I have just discovered we have got a lodging house. . . . Look at the boarders.' But Carrie is testy at being interrupted and refuses to laugh and goes back into house.

Daisy Mutlar, Lupin's first fiancé (94).

They laugh easily and often and not just at puns. Lupin's first (unsuitable) fiancée is Daisy Mutlar. Her brother Frank, a loafer in Pooter's opinion, is the main low comic with the Holloway Comedians, the amateur dramatic society of which Pooter disapproves. Frank plays tunes by tapping a knife blade against his cheek, presumably using his mouth as a sounding board. He then imitates a toothless old man smoking and dropping a cigar. Carrie is in stitches (Victorian humour, we have to admit, has an edge of cruelty to it.)

Some of their jokes though are private and between themselves. One evening, alone together, they are getting ready to go on their annual week's holiday in Broadstairs on the Kent coast.

Carrie has ordered of Miss Jibbons a pink Garibaldi and blue-serge skirt, which I always think looks so pretty at the seaside. In the evening she trimmed herself a little sailor-hat, while I read to her the Exchange and Mart. We had a good laugh over my trying on the hat when she had finished it; Carrie saying it looked so funny with my beard, and how the people would have roared if I went on the stage like it. [The stage looms very large in the entire book: Grossmith can't get away from it.]

The book, too, carries details of the everyday and the overlooked that should interest us all, social historians and lay folk alike. Have you ever wondered how families rubbed along with live-in servants in what were, after all, very small houses? And where master and servant were socially and in terms of class not all that far apart? Pooter arrives home one evening to find the house in uproar. Carrie is outside her (not their?) bedroom too frightened to intervene. Sarah, the maid, has accused the charwoman of stealing kitchen fat and wrapping it in the missing pages of the Diary. The char is incensed: 'there's never no leavings to take. She was a respectable woman. She would smack any one who put lies in her mouth.' She has, in fact, smacked Sarah. Sarah is crying. Lupin is making matters worse and using language he shouldn't in front of his mother. Pooter sorts it out. On another occasion, Pooter tells Sarah off: she can't boil an egg and shakes crumbs from the table cloth on to carpet where they are trodden in. Sarah first argues, then bursts into tears. Pooter hurries away to catch a bus.

How people view Pooter today seems to depend on their politics. In 1996 The Daily Telegraph (a newspaper which Pooter also read) said he was "a decent fellow . . . who is not only a comic archetype but also a moral one. . . . . the kind of worthy and unglamorous figure on whom Britain's prosperity was founded. His values are timeless. He is thrifty, loyal, hard working and distrustful of those on the make."

The Telegraph is Tory-leaning (it's sometimes called the Torygraph) and is a natural supporter of self-reliance, the traditional, and the wisdom of institutions. The Guardian, on the other hand, is left-wing to its core. Like 'Pooter', the phrase 'Guardian reader' has entered the language: it's shorthand for a complete mindset — anti-English, anti-American, pro-public sector, pro-State control. In 1996 The Guardian said of Pooter: 'he is also petty, snobbish and a crashing bore. We don't want more Pooters, we have been governed by one [John Major] for six years."

Critics on the left call Pooter mean, vain, pompous, conceited, naïve and snobbish. Yet Mr and Mrs Pooter were the immediate forerunners and representatives of a new kind of lower middle class, created both by the 1870 Education Act (of which Lupin is a product) and the need for white collar workers in an expanding City, in Banks, and the new department stores. Railways and new bus routes carried them to streets of new houses in villages-turned-suburbs on the hills either side of the river. Their lives must have been precarious; if a working man failed, he could step down a rung of the class ladder. If members of the new Pooter class lost their jobs, they had nowhere to go — except genteel poverty and a life of pretence and hunger. Snobbery was rife, of course; in this they were merely aping their betters — but was there perhaps also a need to boost self-esteem in lives that were far from heroic?

Their culture, by the way, was literary and Pooter does have a set of Shakespeare; he paints the backs red when he is enamelling Sarah's washstand and the bath tub. The backs are well worn, he tells us. He is snobbish but he never gets away with it. He tries to look down on tradesmen but they don't look up to him, and put him down regularly and with ease. Even delivery boys get the better of him. Youths in the office where he's Head Clerk throw paper balls at him and call out names behind his back. Pooter is not an imposing figure. Weedon portrays him as tall, lean, lugubrious with a turned down mouth and a beard without a moustache. He looks serious but is never taken seriously.

A clerk whistles "The Hornpipe" as Pooter passes by, to make fun of his wide-bottomed trousers (63).

He is also much put upon. He's getting accustomed, he tells us, to being snubbed by his son, his wife has a right to do so, but it is a bit much when son, wife, and two guests all snub him in the one evening. He has related a dream of blocks of ice burning in a glare of flame. 'What utter rot,' says Lupin, contemptuously. Gowing says dreams are boring. Cummings agrees. Carrie says he tells her his stupid dreams every morning. Cummings reads them a more interesting story about the superiority of bicycles to horses.

On another occasion, Gowing walks into the drawing room without knocking. He's called to collect his cane which he'd left behind. Pooter, in one of his fits of creativity, has painted it with black enamel. Gowing is furious: 'All I can say is, it's a confounded liberty, and I would add you're a bigger fool than you look, only that's absolutely impossible.' The enormity of the insult sinks in only when you remember the Victorian attachment to hearth and home: his house really was an Englishman's castle, his hearth was sacrosanct (almost literally), and his home was the one place where his dignity had to be respected. (In spite of this, Pooter buys Gowing a silver-topped cane for 7/6d, nearly a week's salary.)

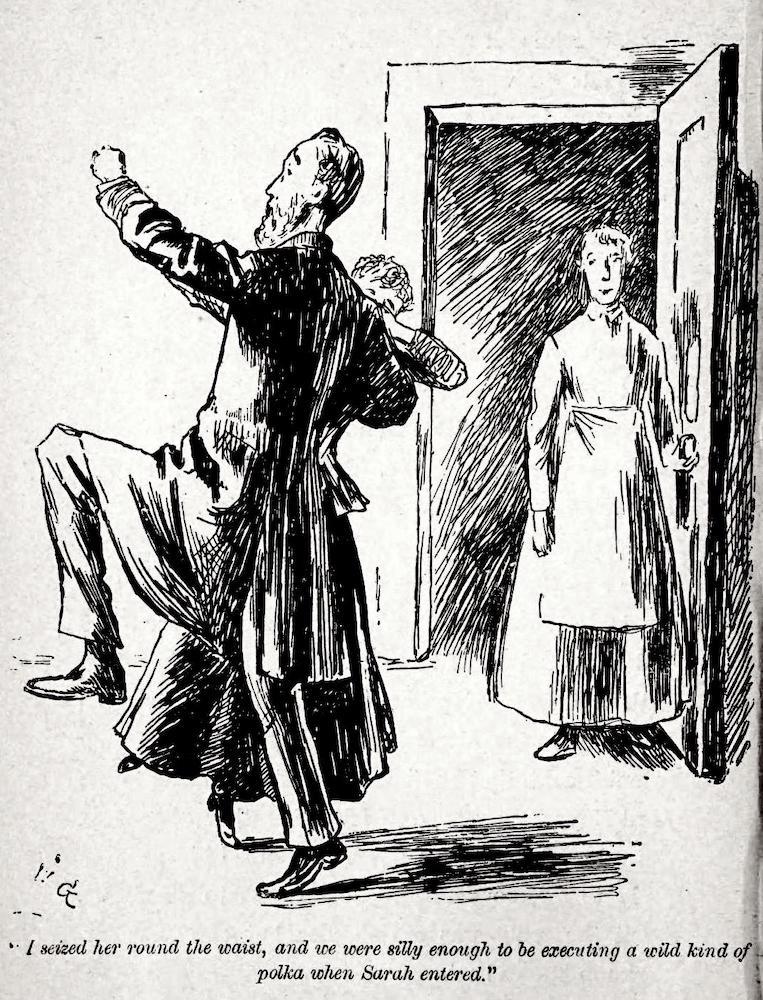

What impressions are left when details of the slapstick and the farce are forgotten? First, there is genuine love and respect between him and his wife: each is proud of the other, each recognises goodness in the other. They seem perfectly matched. When they get the invitation to the Lord Mayor's Ball they spontaneously break into a wild polka in the drawing room. Later that year he writes: 'I spent the evening quietly with Carrie, of whose company I never tire. We had a most pleasant chat about the letters on "Is Marriage a Failure?" It has been no failure in our case. In talking over our own happy experiences, we never noticed that it was past midnight.' They have found human love, which may be rarer than we care to admit.

The Pooters dancing with glee after receiving the invitation to the Lord Mayor's Ball (40).

There are also some nice domestic touches which Grossmith could never have intended to be moving. Pooter is worried that an old school friend of Carrie's is leading her astray, particularly on the subject of clothes. He asks Gowing to supper, presumably to act as a distraction from frock-talk. Carries prepares a light meal: jam puffs (and a decanter of port), blanc mange, custard, cold meat and a little salmon. (She tells Pooter she will offer him some but he must refuse because there isn't enough to go around.) The ruse doesn't work and two days later her friend has dressed Carrie in a smock-frock ('she said "smocking" was all the rage. I replied it put me in a rage') and a hat the size and shape of a coal scuttle.

But Pooter is no lower middle class Prufrock; in his own way he is dynamic, he embraces life and never makes the great refusal. He is not intelligent, not educated, has no privileges of birth. He is not by temperament an empire builder, adventurer, industrialist, politician or pioneer. But he has made the most of what he is and, in spite of his snobbery, doesn't pretend to be what he isn't; he has a place in a hierarchy and that hierarchy makes for an order and stability which protects people like him.

He is also given traits which Grossmith may have meant to be laughable but can strike some people as laudable. Victorian pubs were not allowed to sell alcohol before six o'clock on Sundays except to bona fide travellers, defined as somebody who had journeyed more than three miles. One Sunday, Pooter and three friends walk on Hampstead Heath and on their way home stop at the Cow and Hedge. The gatekeeper asks Pooter how far he has come. Pooter tells the truth and is barred. His friends lie and are let in. Pooter waits outside in a fury. Is he a ninny or a man with a code of honour? Things happen to him; he does very little he need feel ashamed of.

class="tc">The excursion to Hampstead Heath. Left: "Stillbrook lags behind, Going up hill" (19). Right: "Nearly there" (21).

He is also forgiving. On the second day of the Diary we meet Borset, the butterman, touting for trade. Carrie buys a shilling's worth of eggs which are addled. Pooter sends them back with a note telling Borset to expect no more business. That evening Borset is on the doorstep shouting drunken abuse and declaring he'll never serve a clerk again and doubting if a clerk could ever be a gentleman, a deadly insult to Pooter. Nevertheless, next evening Borset is back to apologise. 'He seems after all a decent sort of fellow; so I gave him an order for some fresh eggs.'

Some see Carrie as a cipher, a foil for Pooter. But she is more than that; we see her in a range of moods from loving affection to irritation to blazing anger. Lupin is the second most developed character. He was christened William and known as Willie until he comes back to London from Lancashire when he insists on being called Lupin, his mother's maiden name. More accurately, perhaps, he should be William Lupin-Pooter. (The name, most likely, is another theatrical one — the Lupino family had been actors since the seventeenth century.)

Weedon's drawing of him may offer a deeper insight than his brother's words. He looks not unlike a callow Stan Laurel but with a heartless arrogance he probably won't grow out of. He is attracted to older women who lack his mother's inherent decency. The two he is most taken up with seem peculiarly empty and brassy. To many people Lupin is the more attractive character. Keith Waterhouse — who wrote Mrs Pooter's Diary in the 1980s — called him 'capricious, spendthrift, confident, cheerful and a free spirit.' He's certainly discontented with his lot. The 1870 Education Act was designed to turn out a work force literate and numerate enough to be useful, not well educated. His father lacked the imagination to have been ambitious for him when he was a child. But of the escape routes open to him (hard work in the Colonies was never an option) he chose to marry money. Everybody agrees though he has a head for business. What message, if any, the brothers intended we'll never know (they took no interest in the book afterwards or even spoke about it in their autobiographies): Lupin is the future? Pooter is the past? (The future of course was to be far more appalling than they could ever have imagined.)

Daisy Mutlar, Lupin's first fiancée, is a wrong turning; she has neither looks, money, nor talent. Carrie is unhappy about Daisy but welcomes her as her son's choice. Pooter has his doubts. She can't sing in tune, a bit of a drawback in a singer, you'd have thought. Self knowledge, however, is not hers. His doubts are confirmed when she starts throwing bread at the other guests at his table, a breach of good manners he can barely comprehend. In the end she jilts Lupin and marries Murray Posh, a rich man who makes 3/- hats for the masses.

Left: Lillie Murray, Lupin's second fiancé, and the Pooters' future daughter-in-law (230). Right: Lupin, the Pooters's son (66).

Lupin is soon engaged to Murray's sister. He calls her Lillie Girl though she's in her thirties, also plain (possibly with dyed hair, Pooter suspects) and in a frock which is cut too low. She smokes cigarettes and giggles. 'Her laugh,' Pooter tells us, 'was a sort of scream that went through my ears, all the more irritating because there was nothing to laugh at.' What will become of the pair? In 1915 we can well imagine him as a forty-seven year old war profiteer selling defective footwear to the Quarter-Master General for men at the Western Front. Lillie Girl will be a raddled sixty year old with a smoker's cough.

The brothers, from theatrical Hampstead, are unlikely to have met people like the Pooters, yet they bring them brilliantly to life. On the other hand, characters they must have known are just tiresome. Mr. Burwin-Fosselton, for example, is an amateur actor desperate for the limelight who comes uninvited to The Laurels three nights running to impersonate Henry Irving. An hour of his company would have been too much; a paragraph is too long.

Mr Huttle doesn't quite come off, either, but only because he's unconvincing as an American (then, again, American writers never get English speech exactly right) The Huttle philosophy, however, might have been George Grossmith's own, and it is certainly Lupin's. Go to extremes. Marry a Duchess or her kitchen maid. Don't take the middle way. Mediocrity never built the Brooklyn Bridge. Grossmith had to re-build the Brooklyn Bridge every evening of his life on stage. Would he fail? Forget his lines? Be ruined? Cocaine or morphine very probably kept him going (the coroner at least thought so).

How good is the book? To begin with, it has stood the test of time; never out of print for nearly a hundred and twenty years, and has sold well for a century. It is also written in pared down prose, another legacy of its origin in a popular periodical. This too may be one of several reasons why it appeals to modern readers; Victorians were often so long winded. Like Alice in Wonderland this is swift and brief; very cutting, as well. As story telling, it is expertly crafted.

Evelyn Waugh called it the funniest book in the world. Waugh came from a similar background to the Grossmiths — Hampstead Arty. He, too, was a terrible snob who, as soon as he made money, bought a small stately home and set up as one of the landed gentry. He wrote better and more amusingly than Grossmith — in that sense his books are funnier — but there is a coldness and emptiness in him where there is warmth in Pooter. Others say Pooter is at the same comic level as the Wife of Bath, Falstaff, Mr Pickwick or Bertie Wooster. Yet Wodehouse delights with his uniquely inventive use of language: Pooter is readable, rather than brilliantly well-written, reflecting once again his origins in journalism. Pooter is closer to reality than Wooster's almost wholly imaginary world of pig keeping Earls and batty young things. As for Falstaff — well, Queen Victoria was never going to ask for a Pooterian Merry Widows of Windsor. One was enough.

In the end there is something elusive about why Pooter is such a fine book. Somehow it's better than it should be, given its theme and characters, and is clearly much greater than the sum of its parts. Perhaps the ending gives us the clue. The bulk of the book was written carelessly and quickly in brief weekly bursts. What got on the page, in other words, came uncensored straight from the unconscious. The ending they had to think about consciously, and made a hash of it. Elsewhere on the Victorianweb (Hopkins and the Spiritual) I've argued that great things can happen when the thinking mind is shut down; perhaps Pooter is a lesser example of this? If this is in any way true, Pooter speaks to something deep and perhaps unanalysable in all of us.

Links to Related Material

- Victorian Diaries and Journals (sitemap)

- "Samuel's Sentiments" (a long-running series of columns in the Cardiff Times chronicling with similar humour the (mis)adventures and opinions of the "ordinary man"

- Exploring Suburbia: Dickens on the Mwrgins (includes a paragraph on the Pooters)

Bibliography

Grossmith, George and Weedon. The Diary of a Nobody. London: Penguin, 1999.

[Illustration source]_____. Diary of a Nobody. New York: Tait, 1892. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Library of Congress. Web. 28 February 2024.

Waterhouse, Keith. The Collected Letters of a Nobody. London: Michael Joseph, 1986.

Waterhouse, Keith. Mrs Pooter's Diary. London: Michael Joseph, 1983.

Created 23 August 2006

Last modified 28 February 2024 (illustrations added by Jacqueline Banerjee)