Transcribed, formatted and illustrated by Jacqueline Banerjee. Click on the images to enlarge them, and sometimes for more information about them. —

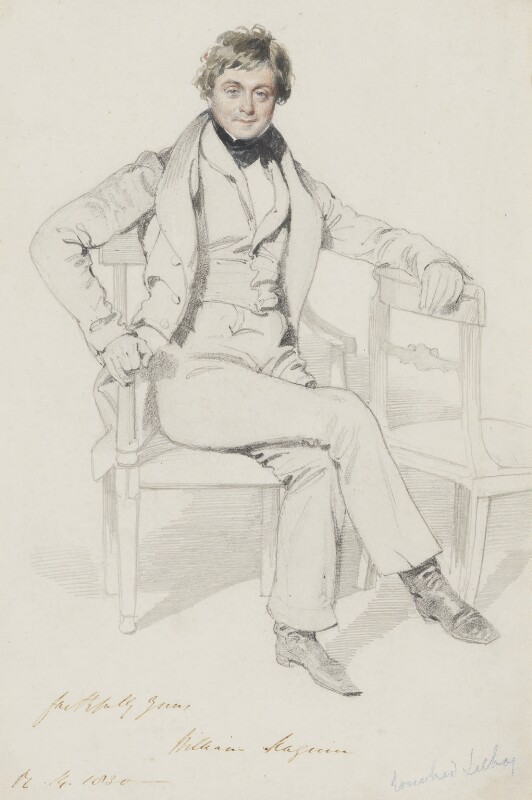

William Maginn, by Daniel Maclise.

On Saturday, the twentieth of August, just as the Morning Star began to glitter in the firmament, and the early sunbeams to come forth, died William Maginn, LL.D., in the forty-ninth year of his age; and on that day week following, his earthly remains were deposited in the quiet little churchyard of Walton-upon-Thames, the hamlet in which he breathed his last. His funeral was quite private, and was attended only by a very few friends who loved him fondly while he lived, and venerate his memory [166/67] now that he is gone; and the tears that fell upon his grave were the last sad tribute to as true, and warm, and beautiful a soul as ever animated a human breast. The place in which he is buried is one that his own choice might have selected, for the Spirit of Repose itself seems to dwell around it, and lends a new charm to its rustic beauty. No noise is ever heard there but the rustling of the trees, or the gay chirp of the summer blackbirds, or the echo of the solemn hymns as they ascend to heaven in music on the Sabbath. Strangely contrasted indeed is its peacefulness with the troublous scenes of his many-coloured life, and provocative of pensive reflection the gentle silence that invests it like a spell. The rude villager, as he passes over his grave, little dreams of the splendid intellect that slumbers heneath, or the host of sweet and noble traits that lived within the heart already mouldering under his feet into a clod of the valley. But his genius has already sanctified the ground, lending to it the magic which entwines itself with the homes or tombs of celebrated men — rendering it henceforward a classic and muse-haunted solitude, to which history will point — and it will be during all time a spot to which the scholar will piously resort, and where the young enthusiast of books will linger long and idolatrously in the soft sunlight or beneath the radiant stars.

William Maginn's grave, marked by a Celtic Cross, close to the church path at St Mary's, the parish church of Walton-on-Thames, Surrey. [Recent photographs by JB]

The character of Maginn, while he lived, was but little understood; and now that he is dead, we hope it will not be misrepresented. Yet rarely has a man of such exalted genius passed from among us without winning that universal celebrity which he so eminently deserved. This disadvantage was chiefly owing to his having confived the labonrs of his mind to periodical literature alone; but in that department who so brightly shone as he?, Who so universal in his knowledge — so profound in his wisdom — so eloquent in advocating the Constitution and the Protestantism of these realms — so terse and brilliant in epigram — so appropriate in anecdote — so simple and luminous in style — so playful and original in wit? Pronounced by a high and amiable authority,* “abler than Coleridge,” he lived without attaining the fame of that extraordinary man; declared by another deep and intellectual observer of his character to be “quite equal to Swift,” he never achieved the authority in literature or the renown that mantled round the head of St. Patrick’s Dean. But great indeed and illustrious must have been the genius which could thus secure the eulogy of two men whose opinions must carry with them respect and consideration, and whose abilities [166-67] and virtues vonch for the sincerity of their sentiments. A brief summary of the leading points of his intellect will enable us to judge whether these praises were inconsiderately conferred, or were the gift of close and accurate observation; and whether to him also may not be applied the saying of Plato on Aristophanes, “that the Graces had built themselves a temple in his bosom,” or the still loftier encomium pronounced by Selden on the learned Heinsius, “Tam severorum quam ameniorum literarum Sol” — a master of all literature — of the beautiful and sublime, of the graceful and the profound.

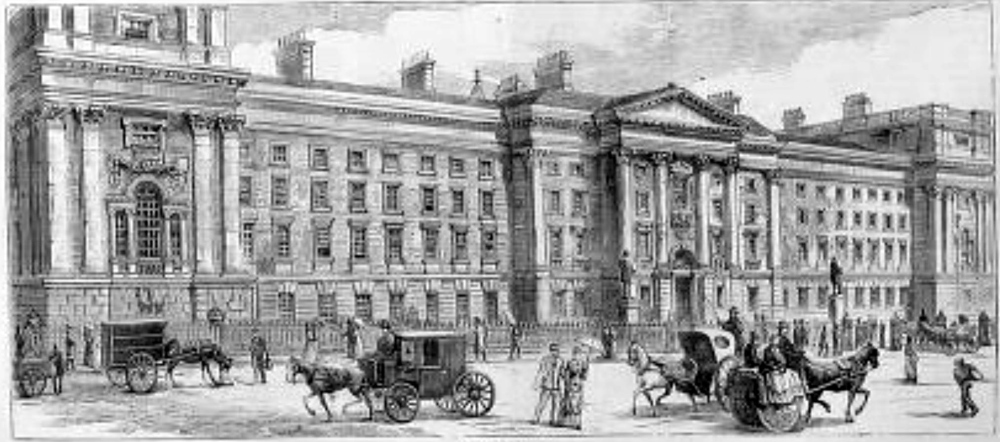

The first and chief attribute of his mind was its originality. The works of no distinguished man, within our reading at least, display the same vein of thought and style. There is scarcely a subject on which he has written that he has not treated in a new manner, illuminating the grave by the liveliness of his fancy, colouring the witty by the solidity of his judgment; for he possessed both in an extraordinary degree, and his mind resembled a mine of gold, curiously prankt on the surface with flowers, but truly valuable within. Nor was his genius acquired by long and patient study; on the contrary, it beamed very beautifully in his earliest years, and was the fair Aurora of his future brilliancy. He entered Trinity College, Dublin, in his tenth year, and was a doctor of laws in his twenty-third — a precocity rivalled but by that of Wolsey, who was a bachelor when only fourteen. And though his reading was immense, no man was less of a copyist of other men’s thoughts, a stealer of other men’s fire, than William Maginn.

Trinity College Dublin in the nineteenth century.

His memory was the strongest in the world, and was a rich storehouse of all learning, so that he might with propriety have been called, like the sublime Longinus, “the living library.” Often, when in want of some scholastic illustrations for our own writings, have we applied to him, and never did we ask in vain. Quotations the most apposite; episodes the most befitting; obscure points of literary history, an elucidation of which we had ineffectually hunted for; sketches of minor literary men of other lands, the difficulty of finding which those conversant with such studies alone can appreciate; stray lines and sentences from authors read only once in a century, and quoted but as curiosities; parallel passages in the Greek and Latin and Italian and German authors: all these he could refer to without a moment’s deliberation, as easily as if they had formed the business of his whole life. And yet, like Scott, no eye ever saw him reading. He seemed a perfectly idle man, and knowledge to come to him by intuition.

Issue of Fraser's containing Maginn's "Homeric Ballads" XII,

and a learned note on a particular Greek word.

His erudition was without pedantry — his mind had no dogmatism. The Avrog sega of the Greek sage did not enter into any of [167/68] his opinions, which were never put forth in conversation but with the most singular modesty. He would talk to you like a little child on the most learned subjects; and whenever he advanced a sentiment, he would turn to his hearer with an appealing look, as if he distrusted his own judgment, and would not willingly mislead another’s. We have seen him listen attentively to the speculations of a boy; gently correcting him when he was wrong, and when he was right entering with alacrity into the spirit of his views, but always more anxious to hear another speak than himself. We do not think he ever uttered a sophism in his life, but was an eager inquirer after truth; and his investigations were like those of another illustrious student — ᾱ̓εί φιλεοντα θέμιστας — who ever loved.‡ His sense of honour was heroic; and he adhered, like Sheridan, inflexibly to his principles, though he might have well calculated. The devotion with which he loved his family is well known, and the memory of it is painted on their hearts. He would instruct his daughters for hours in the beautiful Italian, of which he was a complete master, and the sight of them always brought brightness to his eyes. On his death-bed, the desolate condition in which he knew that he was leaving them was the great sorrow of his soul; but he committed them to the noble generosity of this mighty country, whose charities are more sublime trophies of its greatness than its grandest conquests by sea or on the land.

His poetry was of the highest order of humour — far superior to Swift, and entirely exempt from his grossness and obscenity. Not a single line did he ever write which, dying, he might have wished to blot; not a single impure thought can be discerned in the whole range of his compositions, poetical or in prose. The wildness of his wit was well known; but his muse was always decent, and never arrayed herself in the immodest peplos in which some of our modern authors have shewn her.

His theological knowledge was extensive. He had deeply studied the ecclesiastical writers, and spoke of Hooker and Barrow with rapture. Never lived a man impressed with a more humble sense of his own failings, or with a finer veneration of our Great Creator. He entertained for mankind an enlarged and bewitching love, and conscious of human frailty, never spoke severely of their errors, but always in charity. He did not hold himself aloof from his kind with the sullen dignity of other writers, but mingled with them with the careless, familiar ease of Fielding, or Fox, or Goldsmith; and would share in the noisy sports of younger spirits as if he were a boy him[] self, and not the rival of Swift in all true greatness, and infinitely beyond him in every private trait deserving of our love. His works, when they are collected, will form an imperishable monument of his mind; but his genius, though splendid, was the least of his qualifications: and the writer of this notice can declare that he valued more the kind and gentle heart of his deceased friend than all the glories of his intellect, or the dazzling brightness of his fancy. — Ainsworth’s Magazine.

* Dr. Moir, the far-famed “Delta" of Blackwood.

†Dr. Macuish, the Modern Pythagorean.

‡ Parthenius de Amat. Affect., cap. ii.

Bibliography

Kenealy, Edward. "The Late William Maggin, LLD." The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Vol. 2, Issue 11 (10 September 1842): 166-168. Internet Archive. Web. 29 September 2024.

Created 29 September 2024