rederick Marryat, who published under the name Captain Marryat, only began writing children's books towards the end of his literary career, affectionately calling these five works, "my little income." Marryat based his nearly all of his writings on his own experiences at sea. In fact, he tried to run away from school to pursue a life at sea three times before his father finally found a place for the fourteen-year-old on board the Imperieuse in September 1806. Marryat actually began writing at sea, producing his first manuscript, that of The Naval Officer; or, Scenes and Adventures in the Life of Frank Midway on board the Ariadne in the Atlantic during 1828. By the end of 1830, Marryat resigned from the navy to embark upon his writing career and in 1831, was one of the co-founders of the Metropolitan magazine.

rederick Marryat, who published under the name Captain Marryat, only began writing children's books towards the end of his literary career, affectionately calling these five works, "my little income." Marryat based his nearly all of his writings on his own experiences at sea. In fact, he tried to run away from school to pursue a life at sea three times before his father finally found a place for the fourteen-year-old on board the Imperieuse in September 1806. Marryat actually began writing at sea, producing his first manuscript, that of The Naval Officer; or, Scenes and Adventures in the Life of Frank Midway on board the Ariadne in the Atlantic during 1828. By the end of 1830, Marryat resigned from the navy to embark upon his writing career and in 1831, was one of the co-founders of the Metropolitan magazine.

Although Marryat wrote his early adventure stories for an adult audience, older children found these tales just as engaging. His biographer, Oliver Warner noted that Marryat's second book, Peter Simple "has always been read by older children, and it used to be said to have been responsible for many entries into the navy" (quoted in Spence, 197). However, while Marryat's children's books recount tales of adventure and survival, Marryat continues to combine these with a measure of didactic moral instruction. Thus A.A. Milne remembers Masterman Ready as "combin[ing] desert island adventure with a high moral tone; jam and powder in the usual proportions" (quoted in Spence, 199).

Marryat's works, often subtitled "For Young People", occupy a significant position in Victorian children's adventure literature. They span the gap between traditional eighteenth-century adventure stories originally written for adult consumption and only later adopted by children to the advent of real adventure stories intended for children. By the mid-nineteenth century, the primarily didactic and moral writings of evangelical writers formerly regarded as the only proper reading material for children was increasingly challenged by less overtly instructional and more truly entertaining works. Thus both in material and tone, Marryat's work, while still displaying didactic tendencies but nonetheless based in exotic adventure, aptly reflect the shifting mid-Victorian attitudes towards what was considered proper children's reading material.

A page from a chapbook adaptation of Robinson Crusoe and a detail from this page. [Click on the thumbnails for larger images.]

Up until and throughout the nineteenth century, English children eagerly perused Daniel Defoe's The Life and Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe... Written by Himself. First published in 1719, Robinson Crusoe and its contemporary, equally popular Gulliver's Travels, was intended for adults although both were largely enjoyed by younger readers. Both were extensively abridged and re-published in simpler forms. For instance, in a study of boy's adventure stories, Dennis Butts estimates that between 1719 and 1819, Robinson Crusoe underwent approximately 150 abridgements published as chapbooks for children (446). Amidst the flurry of Robinsonnades, stories modeled on Robinson Crusoe, J.D. Wyss's The Swiss Family Robinson written in 1812 and translated into English in 1814 stands out. However these early adventure stories remained largely condemned by outspoken evangelical supporters and furthermore, the emphasis on real facts and scientific knowledge embodied by the popular Peter Parley publications of the 1830s resulted in the criticism of the old Robinsonnades as too fantastical.

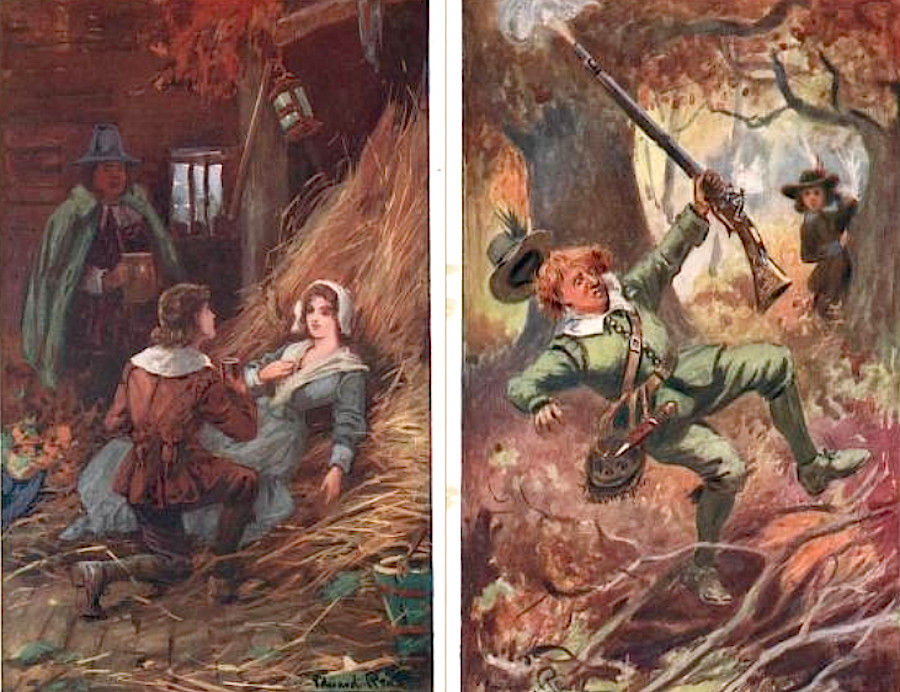

Two of Edward Read's full-page colour plates for Marryat's Children of the New Forest, 1847.

Butts points out that Marryat almost singlehandedly reintroduces the adventure story for children and inspired the works of later nineteenth-century writers, most famously R.M. Ballantyne, R.L. Stevenson and H. Rider Haggard who all tell of adventures in exotic locales and a strong dose of British superiority (449). Indeed, while Marryat's early work, notably Masterman Ready remains didactic, at points overtly moral in tone and moreover encompasses a Peter Parley-esque emphasis on scientific observation and focus on nature, Marryat also produced exciting tales of hardship and survival. In fact, Butts notes that Marryat's later children's books, for instance The Children of the New Forest lacks the underlying piousness of Masterman Ready and sets the stage for later children's writers to eschew moral instruction altogether in favor of good English schoolboy fun (453).

References

Butts, Dennis. "The Birth of the Boys' Story and the Transition from the Robinsonnades to the Adventure Story" Revue de litterature comparée. No. 304 (2002.4).

Marryat, Frederick. The Children of the New Forest. London: George Routledge, 1847 / Athelstane e-Books. Internet Archive. Uploaded by Nick Hodson. Web. 9 August 2016.

Spence, Nigel. "Frederick Marryat" British Children's Writers, 1800-1880. Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 163. Meena Khorana, ed. Detroit, MI: Gale Research, 1996.

Last modified 9 August 2016