This review first appeared as part of a longer review article in the Times Literary Supplement of 25 February 2021, entitled, "Virtually Victorian: A return to formal engagement with the novel." It has been slightly adapted, reformatted, linked and illustrated for the Victorian Web by the author. Click on the images to enlarge them, and to find out more about them.

Recent critics have been looking closely at the actual experience of reading, of becoming absorbed in and emotionally participating in a fictional world. They have written revealingly about their literary encounters, and about how these encounters have touched on or even transformed their lives. With its strong confessional element, this kind of critical work appeals to a wide audience, giving insights into the creative process enjoyed by authors and readers alike. Concurrent with this "experiential turn" (Gao 2), perhaps prompted by it, has been a new way of looking at early reading experience too — not for its potential to inculcate good behaviour or promote mental acuity, but for the ways in which it encourages empathy. Right from the start, it seems, to lose oneself in a fictional world is to find oneself, and, inseparably from that, to appreciate more fully one's connection with others.

But can the critics carry this "experiential" approach any further without seeming self-indulgent? In her influential Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network of 2015, Caroline Levine argued that too much attention was being paid to "antiformal experiences" (9) and here is a recent book about Victorian fiction that cites her, and, to some extent, tilts the emphasis back towards textual production — to how that appealing fictional world is created.

Close to "experiential" criticism, and avowedly so, Timothy Gao's Virtual Play and the Victorian Novel balances the emphasis on the reader's therapeutic gains with close attention to the author's own process of make-believe. Reminding us that Coleridge himself deplored "vacant absorption" in a book (109), he explores each fictional world not simply with a "willing suspension of disbelief," but in an active bid to uncover its own form of "worldplay" (24) and the uses to which it is put. Looking in turn, though not exclusively, at Charlotte Brontë's The Professor, Trollope's The Small House at Allington, Thackeray's The Newcomes and Dickens's Little Dorrit, Gao is particularly interested in the gap between the virtual realities that they present, and common experience — a gap that can seem uncomfortable, and attract criticism, but has its own positive uses.

Gao turns first to the Brontë siblings' juvenilia, with its all-powerful author figures, collectively known as the "Chief Genii." He is hardly the first to do so, but, in examining the practice and development of the siblings' story-telling skills, he finds something rather different from previous critics — a willingness to accept and capitalise on the neglected area between the wished-for and the likely. Here, says Gao, lies a "plausible yet explicitly conjured reality," as sophisticated in its own way as any more complete "correspondence between life and fiction" (57). This encourages him to challenge the widely-held view that The Professor is more grounded than Jane Eyre. Focussing on the partial wish-fulfilment and half-acknowledged fantasy in which its main characters, Francis Henri and William Crimsworth, indulge, he recognises a conscious return to "Genii authorship" (11). Others may look askance at this authorial strategy, this kind of "playing at verisimilitude" (26). But Gao enjoys the inventiveness involved, and the satisfactions that accrue for both the protagonists and the reader.

The emphasis on pleasure in this thoughtful and uplifting study is heartening. Gao's theory of paracosmic immersion certainly helps to explain the reluctance of the author to leave the fictional world. This reluctance shows up in Trollope's long unplanned sequence, the Chronicles of Barsetshire, and also in Thackeray's reintroduction of earlier characters and places (especially Grey Friars school) in later work. Magazine serialisations and triple-decker novels encouraged Victorian readers to stay with these authors in their "virtual worlds," but, even now, we enjoy finding familiar fictional personages and locales in an author's later work. Our attachment is also demonstrated by the popularity of prequels, sequels and even midquels, as well as the novel series or, indeed, the film, television or video-game series. In a letter to The Daily Telegraph, quoted by Gao in his chapter on Thackeray, John Ruskin memorably complained about invented worlds that end once and for all, thereby "shifting the scenes of fate as if they were lantern slides" and "tearing down the trellises of our affections that we may train the branches elsewhere" (605). How much better to linger longer with the novelists in their imaginary worlds!

But does this encourage sentimental, or at least uncritical, writing and reading? Trollope, for instance, had an enviable fluency, but confessed to more or less making up the Chronicles of Barsetshire as he went along. In tackling this, Gao finds a parallel with the incomplete and "undecided" childhood world of the young De Quincey brothers (82), and examines signs of Trollope's improvisation, like theirs, for its positive uses. One of his examples is Mrs Dale's sudden decision to stay in the eponymous "small house at Allington," which she had previously felt strongly obliged to leave. Gao argues that this says more about possibilities than improbability: "what such examples recommend is more creative morals, not less; better revisions, rather than stronger resolutions" (97). In this way he consistently sees his chosen authors using events in the narrative to reflect on rather than coincide with expectations.

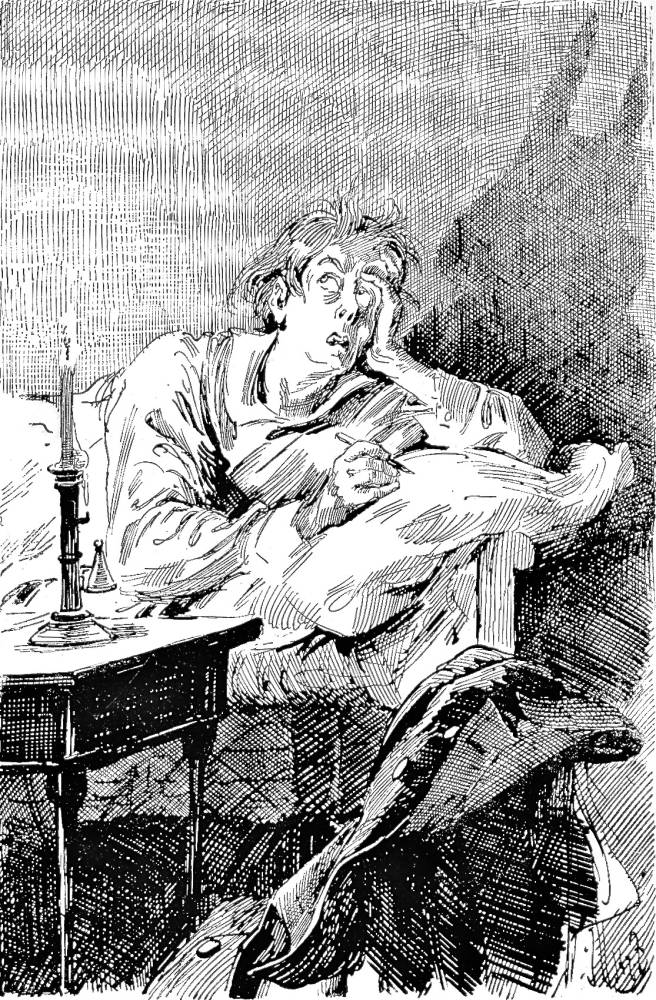

John Chivery pens his own epitaph, by Harry Furniss.

He has more to say about such oscillations, as well as attachments and, finally, detachment, in his chapter on Thackeray; but his strongest, most generous appreciation is of Dickens. Here, he feels, is an author whose imagination is so dynamic that even a minor character like John Chivery, Amy Dorrit's disappointed suitor, has a fully realised inner world. He has put aside his personal feelings to help Amy find happiness with Arthur Clennam. At the end, Chivery reinterprets his life, not in order to claim outward success like William Crimsworth in The Professor, but to take due pride in his own magnanimity. In this case, the creative imagination negotiates with experience to console, another of the "manifold resources for living" that it offers (173), not just to individual characters, but, through them, to the reader. Chivery's imagined new inscription for his headstone ("Stranger! Respect the tomb of John Chivery, Junior"), is hardly a high point on which to end the chapter; there is too much pathos attached to it. But it is in such cases that consolation is most needed.

English departments do seem to be at a crossroads, either stretching formalism to include other approaches, or incorporating it into those approaches. If Gao's book is an example of this current position, then it is a very good place to be, making us delve deeply into narrative practice and at the same time showing us how immersion in created worlds can give us other, more encouraging ways of looking at our own endeavours.

Bibliography

[Book under review] Gao, Timothy. Virtual Play and the Victorian Novel: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Fictional Experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021. 222 + vi. pp. 978 1 108 83716 3 £75.00

Levine, Caroline. Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network. 2015. Pbk ed. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2017.

Ruskin.John. "Novels and Their Endings." The Works of John Ruskin. Edited by E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. Vol. 34. London: George Allen, 1908.

Created 2 July 2023