uskin began the Seven Lamps of Architecture arguing that lavishing money and other resources on church architecture followed the Bible’s demand for literal and extended Levitical sacrifices. “The Lamp of Sacrifice” (text), which drew upon sermons that Ruskin had paraphrased as a child, shows him trying to convince evangelicals within and without the Church of England to abandon their plain, often ugly houses of worship and construct those that resemble those of Roman Catholics and establishment Anglicans. Given the passion with which Ruskin both makes this argument and devotes much of later The Stones of Venice praising gothic architecture, it is therefore very surprising to read that church architecture does not necessarily have to be gothic. “We attach,” says Ruskin, “a kind of sacredness to the pointed arch and the groined roof, because, while we look habitually out of square windows and live under flat ceilings, we meet with the more beautiful forms in the ruins of our abbeys.” But we are wrong, as he argues a few year later in “Traffic” (text), to separate our religion from our everyday lives, our church architecture from that used for homes, civic structures, and commercial ones, because “when those abbeys were built, the pointed arch was used for every shop door, as well as for that of the cloister, and the feudal baron and freebooter feasted, as the monk sang, under vaulted roofs; not because the vaulting was thought especially appropriate to either the revel or psalm, but because it was then the form in which a strong roof was easiest built.” After surprisingly offering an essentially functionalist defense of gothic, he next claims that in abandoning this architectural style, “we have destroyed the goodly architecture of our cities; we have substituted one wholly devoid of beauty or meaning; and then we reason respecting the strange effect upon our minds of the fragments which, fortunately, we have left in our churches, as if those churches had always been designed to stand out in strong relief from all the buildings around them, and Gothic architecture had always been, what it is now, a religious language, like Monkish Latin” (10.119).

uskin began the Seven Lamps of Architecture arguing that lavishing money and other resources on church architecture followed the Bible’s demand for literal and extended Levitical sacrifices. “The Lamp of Sacrifice” (text), which drew upon sermons that Ruskin had paraphrased as a child, shows him trying to convince evangelicals within and without the Church of England to abandon their plain, often ugly houses of worship and construct those that resemble those of Roman Catholics and establishment Anglicans. Given the passion with which Ruskin both makes this argument and devotes much of later The Stones of Venice praising gothic architecture, it is therefore very surprising to read that church architecture does not necessarily have to be gothic. “We attach,” says Ruskin, “a kind of sacredness to the pointed arch and the groined roof, because, while we look habitually out of square windows and live under flat ceilings, we meet with the more beautiful forms in the ruins of our abbeys.” But we are wrong, as he argues a few year later in “Traffic” (text), to separate our religion from our everyday lives, our church architecture from that used for homes, civic structures, and commercial ones, because “when those abbeys were built, the pointed arch was used for every shop door, as well as for that of the cloister, and the feudal baron and freebooter feasted, as the monk sang, under vaulted roofs; not because the vaulting was thought especially appropriate to either the revel or psalm, but because it was then the form in which a strong roof was easiest built.” After surprisingly offering an essentially functionalist defense of gothic, he next claims that in abandoning this architectural style, “we have destroyed the goodly architecture of our cities; we have substituted one wholly devoid of beauty or meaning; and then we reason respecting the strange effect upon our minds of the fragments which, fortunately, we have left in our churches, as if those churches had always been designed to stand out in strong relief from all the buildings around them, and Gothic architecture had always been, what it is now, a religious language, like Monkish Latin” (10.119).

Examples of the kind of architecture to which Ruskin refers: Left: A.W.N. Pugin’s Cathedral of St Barnabas (1841-44). Middle: Salisbury Cathedral (1120-58). Right: The Neoclassical Architecture of Sir Robert Smirke’s British Museum (1823-47). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Ruskin, who knew that many in his intended audience associated gothic with Roman Catholics — the Church of Rome — and High Anglicans in the Church of England, and he therefore argues that that these believers, who supposedly have little else going for them, cleverly draw upon the popular, unthinking association of gothic architectural style and religion: “the High Church and Romanist parties have not been slow in availing themselves of the natural instincts which were deprived of all food except from this source; and have willingly promulgated the theory, that because all the good architecture that is now left is expressive of High Church or Romanist doctrines, all good architecture ever has been and must be so,—a piece of absurdity from which, though here and there a country clergyman may innocently believe it, I hope the common sense of the nation will soon manfully quit itself.” Ruskin here employs all the tool of rhetoric, arguing that only an ignorant “country clergyman” or someone unmanly would credit such a connection. According to Ruskin, “it needs but little inquiry into the spirit of the past, to ascertain what, once for all, I would desire here clearly and forcibly to assert, that wherever Christian church architecture has been good and lovely, it has been merely the perfect development of the common dwelling-house architecture of the period;1 that when the pointed arch was used in the street, it was used in the church; when the round arch was used in the street, it was used in the church: when the pinnacle was set over the garret window, it was set over the belfry tower; when the flat roof was used for the drawing-room, it was used for the nave. There is no sacredness in round arches, nor in pointed; none in pinnacles, nor in buttresses; none in pillars, nor in traceries.”

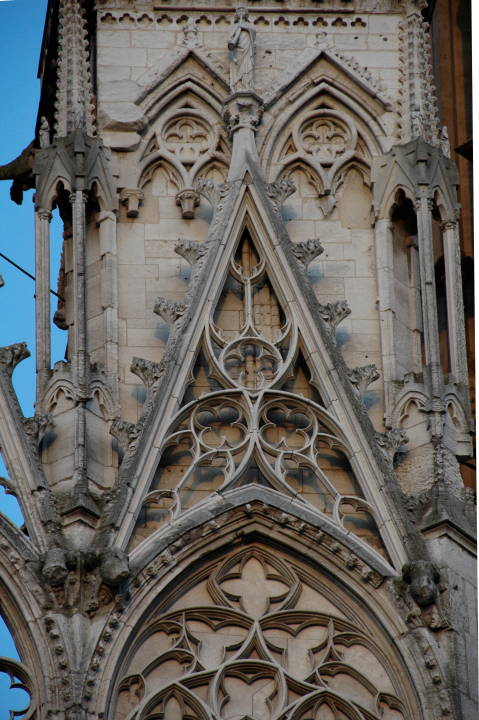

Examples of Gothic traceries Ruskin discusses in The Seven Lamps of Architecture. Left: Details of the West Front of Rouen Cathedral Early Evening Light. Middle: Tracey near the Cathedral’s North Door. Right: . [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Attempting to explain the obvious differences between churches and non-ecclesiastical structures, he returns to his functionalist argument and tells his readers that “Churches were larger than most other buildings, because they had to hold more people; they were more adorned than most other buildings, because they were safer from violence, and were the fitting subjects of devotional offering: but they were never built in any separate, mystical, and religious style; they were built in the manner that was common and familiar to everybody at the time. The flamboyant traceries that adorn the facade of Rouen Cathedral had once their fellows in every window of every house in the market-place; the sculptures that adorn the porches of St. Mark’s had once their match on the walls of every palace on the Grand Canal.”

Left two: Examples of Sculpture and Stone Carving on St. Mark’s, Venice. Right: The Palazzi Cavalli on the Grand Canal, Venice. Ruskin’s claim only rings true if by sculpture we include window tracery as well as statues.

Bibliography

Ruskin, John. The Works. Ed. E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. “The Library Edition.” 39 vols. London: George Allen, 1903-1912.

Last modified 13 April 2020