Adapted by the author from Chapter 8 of her book, Literary Surrey (Headley Down: John Owen Smith, 2005), and illustrated with images from: the National Portrait Gallery, London; the Project Gutenberg version of Wells's autobiography (see "Sources"); and her own photographs. You may use all but the first without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer or source and (2) link your document to this URL or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on all the pictures to enlarge them.]

Early Life

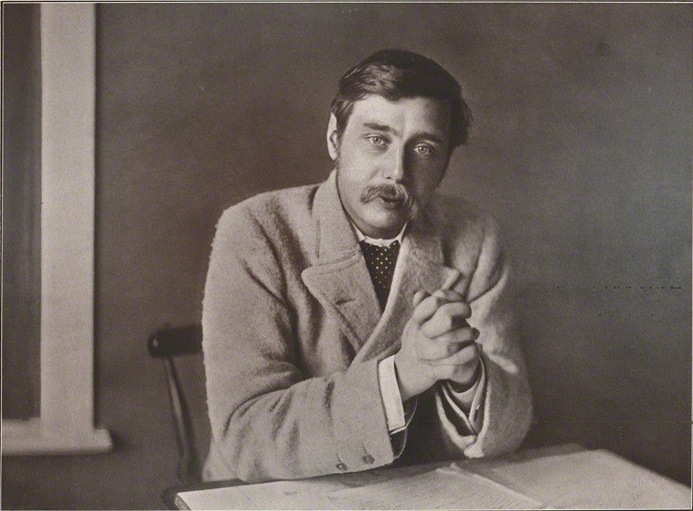

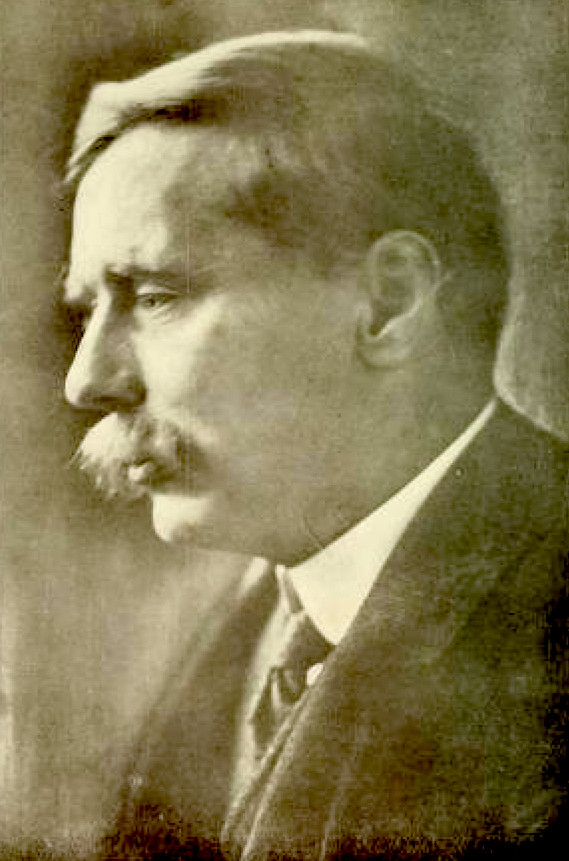

H. G. Wells, 1901 © National Portrait Gallery, London (reproduction of a phtograph by Ellioot & Fry, NPG x45778).

Herbert George Wells was born in 1866 in Bromley, Kent (now a borough of Greater London), as the third son of a shopkeeper. His father Joseph had a more interesting background that that suggests, having earlier been a professional gardener at the grand house of Uppark in Sussex. In the early 60s Joseph Wells had also been a celebrated Kent county cricketer, and now sold cricketing equipment, as well as china goods and so on, in his Bromley High Street premises. But business was bad and went downhill fast after he broke his leg in 1877. He went bankrupt, and his wife left him in 1880. She had met him at Uppark, where she had been in service as a lady's maid, and now she was taken back there as housekeeper.

Barely into his teens, Wells was taken out of school when the family broke up, though the library at Uppark provided him with rich new resources for a broader education (see Hammond, Preface, 209). After a brief spell as a student-teacher, he was set to follow his elder brothers into retailing. In fact, his experiences as a young assistant in a pharmacy and an apprentice in the drapery trade in the early 80s provided him with useful material, later, for novels like The Wheels of Chance (1896), Mr Kipps (1905) and Tono-Bungay (1909). But he managed to get his mother to pay him out of his indentures at a Southsea drapers, and became a teaching assistant again. Then, having applied himself strictly to studies in science, he won a scholarship in 1884 to the Normal School of Science (later subsumed into Imperial College) in London, where he was lucky enough to study for a while under T. H. Huxley. In this way, by his own drive and intelligence, he managed to escape his allotted fate and put himself on track to overcoming the disadvantages of his background.

There was another problem to overcome, too. That was the ill-health which had dogged him, first as a whey-faced child on the outskirts of London, then as a hard-driven apprentice. In the summer of 1887 he also sustained a serious injury on the football pitch during a short stint as a teacher in North Wales. Even after recovering and completing his degree, his efforts to get a foothold in the literary world, while still teaching, put more strain on him. The last straw was trudging round London in all weathers to write theatre reviews. Never robust, he was displaying symptoms of tuberculosis. At this point, he decided to move out to Surrey.

A Fresh Start

Left to right: (a) The house on Maybury Road, Woking, Surrey. (b) Close-up of the plaque on the façade. (c) The Basingstoke Canal not far behind, and parallel to, the Maybury area, still preserving stretches of nature for wildlife (and leisure boating, in season).

Wells was not alone now. His "withdrawal," as he put it in his autobiography (457), was also partly due to the complications of his love life. His first youthful marriage to his cousin Isabel, in 1891, had failed, and he was now living scandalously with a student from one of his science classes, the diminutive and rather fragile Amy Catherine Robbins (whom he called Jane or, more evocatively and affectionately, "Miss Bits" or even just "Bits"). Along with its fresh air, and the convenience of its fast and frequent train service to and from London, the commuter town of Woking offered him a life out of the public eye. It was just the place in which to lie low until his divorce came through and he was free to remarry.

In 1895, therefore, the couple took a house there called Lynton, one of the typical Woking semis ribboning out along the railway tracks. Wells himself described it as a "small resolute semi-detached villa with a minute greenhouse in the Maybury Road facing the railway line," where, he noted in his autobiography, "all night long the goods trains shunted and bumped and clattered" past their front windows. But close at hand was

a pretty and rarely used canal amidst pine woods, a weedy canal beset with loose-strife, spiræa, forget-me-nots and yellow water lilies, on which one could be happy for hours in a hired canoe, and in all directions stretched open and undeveloped heath land, so that we could walk and presently learn to ride bicycles and restore our broken contact with the open air. [Experiment, 457-58]

Just as he had hoped, their stay there was liberating for both of them.

Wells had already published some fiction, examples of which appeared in the collection of short stories that made up The Stolen Bacillus and Other Incidents (1895). But now that he was able to devote himself full-time to writing, he wrote at a phenomenal rate. The Time Machine had already been serialised; it was due to appear in book form that very spring (1895). There followed, in rapid succession, and to list only the novels: The Wonderful Visit (1895), The Wheels of Chance and The Island of Doctor Moreau (both 1896), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898), When the Sleeper Wakes (1899), Love and Mr Lewisham (1900) and The First Men in the Moon (1901).

Wells's Second Marriage

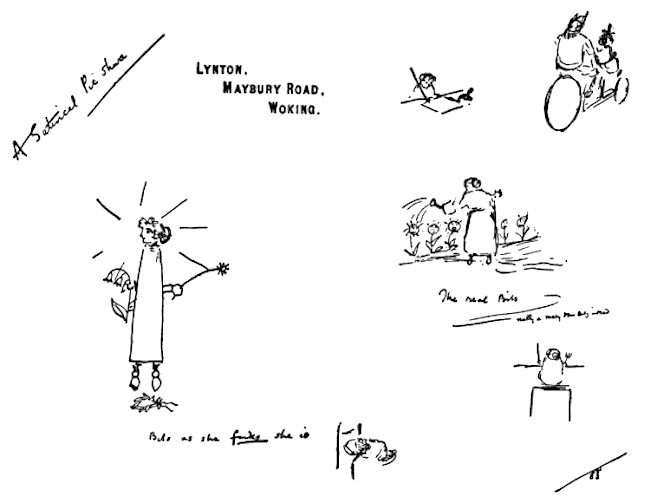

Captioned: "a Satirical Picshua, on one side of the paper is 'Bits as she finks she is' and on the other, 'the real Bits, really a very dear Bits indeed.' She writes, sleeps, eats and rides a bicycle with me" (Experiment: 368).

Indeed, this was an altogether satisfactory time for Wells. He and Jane finally got married at the end of a busy cycling autumn, on 27 October 1895. Not that the marriage itself was important to him. It was undertaken largely because of social pressures. "Directly the unsoundness of our position appeared, servants became impertinent and neighbours rude and strange" (364), he complained. Still, as he himself said, "We lived very happily and industriously in the Woking home" (Experiment, 458). He explains that they were quite isolated there, and that helped. There was no one else for either of them to turn to when they had some difference of opinion. One of his funny little "picshuas" from this period shows "Bits as she finks she is" (floating radiantly like an angel), and the common facts of the case on the other side, as she carries out her daily activities, including watering the flowers. Nevertheless, he writes in the middle of the realistic sketches that she is "really a very dear Bits indeed" (Experiment, 368).

Jane, or Miss Bits, would later bear him two sons, and she would always be essential to his life, even though he had other affairs, notably with Rebecca West, whose son Anthony has written one of his best biographies. With remarkable objectivity and understanding, West writes that his young and beautiful mother was a kind of tonic for Wells, but that all the same, "he had to have Jane as the balance wheel of his existence" (21). And, despite his womanising, before, during and after the marriage, Wells never remarried. As for Jane herself, she was always loyal to him, and never let him down despite his various affairs. He wrote later, at the end of the first volume of his autobiography, that she was "the moral background of half my life" (313). When she fell ill with cancer in 1927, she was living alone in London, but wrote to tell him. He hurried to her, stayed with her till the end, and was so grief-stricken at the funeral that the ceremony became an ordeal for his fellow-mourners. As Norman and Jeanne MacKenzie, who have also written a biography of Wells, conclude, "Their marriage had failed long ago, in the conventional sense. And yet, in a different sense, it had succeeded, and survived to the end" (354). In this way, the married life that started in Woking was profoundly important to Wells's happiness and success in life.

Fame at Last

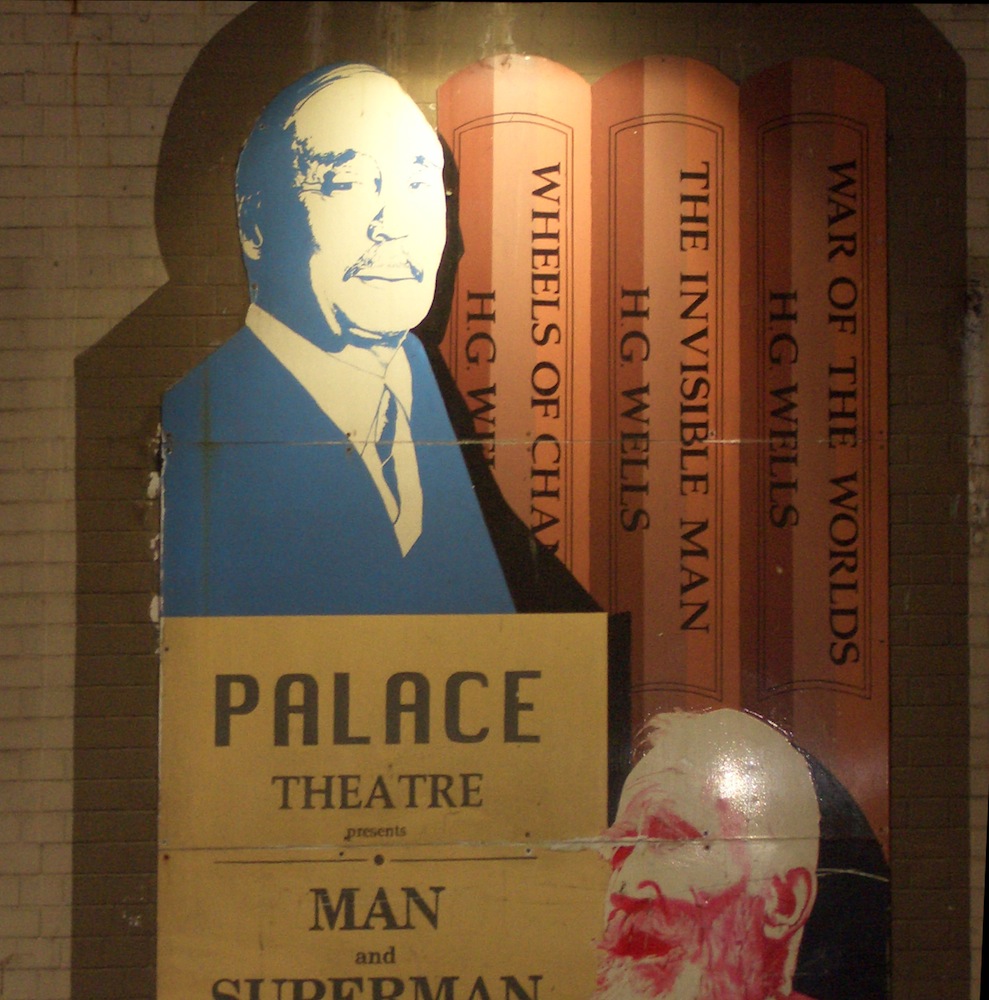

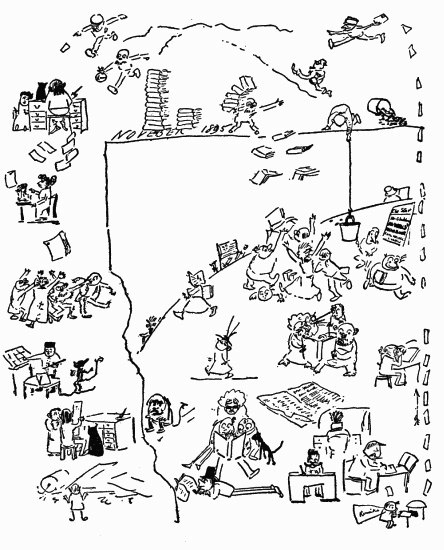

Left to right: (a) Another of Wells's "picshaus," showing him as a cat with his loot, marked £200 (Experiment, 469). (b) Wells's success celebrated in a mural under a railway bridge in Woking, where George Bernard Shaw appears below him. (c) This "picshau" shows Wells in the thick of his literary productivity, and people fighting to get his work hot off the press (Experiment, 470).

And success, real success, was now just around the corner. The War of the Worlds, also begun and mostly written to the sound of trains rattling past, would consolidate his growing reputation and relieve him of all financial insecurities. When the Authors' Syndicate asked to see the rest of this narrative soon as possible, Wells sketched one of his "picshuas" at the end of the letter. It is, he admits, "vain-glorious to the ultimate degree" (467). Yet there is something very touching about the image of him as a cat, proudly bearing home a sack marked £200 to his beloved "Miss Bits" after having left his long looping "tail" (seen in the middle of the page) behind at the publisher's! Another self-congratulatory sketch, shown on the right above, shows a newspaper billboard advertising "Mr Wells's New Book," and people absolutely falling over themselves to get hold of their copies. Wells must have felt that he, like the Martians, was right on target for his conquest of the general public.

Interestingly, the other popular "scientific romance" which Wells planned and wrote in Woking in these late-Victorian years, The Invisible Man (1896), is set in a Sussex rather than a Surrey village (although the West Surrey Gazette is mentioned in Chapter 12 — a slip of the pen, perhaps). Probably he decided that a more thoroughly rural background was required here, especially in the comic opening chapters before Griffin, the young student hero, is "unveiled" by the nosy villagers. But perhaps, too, Wells thought that Surrey people would have been too blasé to take an interest in a stranger, however peculiar, at least until they felt their lives were under threat.

Wells lived in Woking for less than two years, but the town's pride in his work is completely justified. He arrived in 1895, at a critical point in his literary and personal development, and was happier and more productive here than he had ever been before. The novels that he published, planned and/or worked on in Woking would make his name and his fortune. Among them, The Wheels of Chance (1896) and The War of the Worlds itself, draw heavily on the topography of the surrounding countryside. In fact, neither of these popular but very different kinds of books could have been written in a more appropriate place.

The Next Step

Wells with George Bernard Shaw, one of his growing number of literary friends (by E. Harries, in Hopkins, facing p. 160).

Yet the now famous author was not ready to leave the county yet. When the couple moved from Lynton later in 1896, it was only to Worcester Park on its northern edge, just east of Surbiton. There were several reasons for the move. Lynton had been cramped, even for just the two of them — Anthony West explains that the dining table had to be cleared for Wells to work on it. The noise of the trains was now bothering him, too. Besides, with fame had come money, and a sense of security: Wells was publishing one book after another, including the Darwinian novel which he had first drafted in London, The Island of Dr Moreau (1897). There seemed no end to his fecundity. He could afford to rent a bigger place. The immediate explanation for the move, though, was that Jane's mother had fallen ill, and needed to come to them. They had to be able to accommodate her properly.

The new place was called Heatherlea. It was another Victorian "villa" near a station, but Wells's improved finances were reflected in its improved status. It was detached, and stood on a good residential avenue out of earshot of the trains. The great advantage of it was that it had two large rooms downstairs, as well as what Wells called "a visitor's room." Here they could entertain, and began, as he explained, "keeping open house on Saturday afternoons which improved our knowledge of the many new friends we were making." They even had a gardener here, one day a week. This house, unfortunately, was demolished in the 1950s, and there are flats, offices and so on along the road now. Wells has no more to say about it, or his life there, in his autobiography. "I think I have sufficiently conveyed now the flavour of my new way of life," he remarks, "and I will not go with any great particularity into the details of my history after we moved to Worcester Park" (Experiment, 471).

Heatherlea was demolished in 1955. There is, however, a description of the house and the general layout of the area, disguised as "Morningside Park," in the first chapter of a later novel, Ann Veronica (1909):

There was first the Avenue, which ran in a consciously elegant curve from the railway station ... with big yellow-brick villas on either side, and then there was the Pavement, the little clump of shops about the post office, and under the railway arch was a congestion of workmen's dwellings. The road from Surbiton and Epsom ran under the arch.... [6]

He goes on to describe the new houses which were growing up near the station in terms of "a bright fungoid growth in the ditch" (6). The Avenue is still there, as of course is the station and bridge, but the most interesting point of the description is that it shows how quickly Wells's standards were rising. He could now afford to pour scorn on cheap housing, both old and new. And well he might, because, according to one of his contemporaries, the editor and journalist Arthur Lawrence, Heatherlea was "quite an ideal home for a literary man" (in Hammond, H. G. Wells: Interviews and Recollections, 2). His whole lifestyle seems to have been on a different level now. It is painted in vivid detail by the pioneering stream-of-consciousness novelist Dorothy Richardson, an old school-friend of Jane's, who came to stay with them. Wells features as Hypo Wilson in The Tunnel (1919), part of her autobiographical Pilgrimage, and is pictured by Richardson's young narrator Miriam as a "little fair square man not much taller than herself, looking like a grocer's assistant with a curious, kind, confidential ... unprejudiced eye" (110). The brown decor, Japanese prints and high-backed chairs downstairs seem oppressive to Miriam at first, and she is uneasy at having to contribute to all the clever literary talk. She comments on "Mr Wilson's" drooping moustache, his squeals, his open-mouthed guffaws, his sociability and his certainty about things. By the time she is on the train back to London, she is in two minds about ever returning. Later, however, she is jealous of their life going on there without her.... "One ought to be there every day," she thinks (141). Dorothy Richardson too would become one of Wells's many lovers.

At Heatherlea, Wells was consolidating his fame by writing works like The Sleeper Wakes (first published in The Graphic magazine, 1898-9), and the more conventional Love and Mr Lewisham (1900). Yet perhaps the most exhilarating aspect of this period was, in fact, the social one. He was now on good terms with many of the literary names of his day, some of them also with local connections. These included George Bernard Shaw, whom he had first met in 1895, and who later lived in Woking and then in Hindhead; the elderly George Meredith and two other novelists in the Dorking area, Grant Allen, who lived there from 1881 until his death in 1899, and George Gissing, who had struggled up from humble beginnings like Wells himself, and who first came to Dorking in 1895. "I asked him to come over to us at Worcester Park," says Wells of Gissing, "and that was the beginning of a long intimacy" (Experiment, 481). He declared a literary debt to Grant Allen, a Darwinist like himself, and acted as a Good Samaritan to the troubled Gissing, whom he nursed on his deathbed. Probably he owed something to each of them. Like Meredith's Diana of the Crossways of 1885, Gissing's The Odd Women (1893), and Allen's The Woman Who Did (1895) both helped to open the way for Wells's own Ann Veronica, with its scandalous "new woman" heroine. In time, Wells's net would spread, and he would get to know everyone there was to know in the literary world.

The End of an Era

H. G. Wells, now a well-established author (Beresford, frontispiece).

By 1898 Wells was, to borrow the heading of this section of his autobiography, "Fairly Launched At Last." He and "Miss Bits" were ready to move on. First they travelled to Italy in the spring of 1898, spending one month in Rome with Gissing, and then doing some touring by themselves. Then they went off on another cycling trip to the south coast. Here, Wells fell ill again, and was advised by the doctor not to return to Worcester Park. Instead, the couple rented a cottage right on the sea front at Sandgate in Kent. Jane went back to Surrey alone to pack up their things, and Wells soon set about having a fine house built down in Kent, by the excellent architect C. F. A. Voysey. The builders had started work by May 1900, and he reported to Gissing on 19 October that year that it was nearly finished (see Mackenzie 150). He was settling down to family life now, and not only the Surrey chapter but also the Victorian chapter of his life was over. As he said himself, "stability and respectability loomed straight ahead of us" (Experiment, 546).

Fortunately, Wells's health would bear up. There would be more books, more triumphs, children (both legitimate and illegitimate, including Anthony West), and various honours, although not those that a more conventional author of his stature might have won. He would return to London for the last sixteen years of his life, an established figure who nevertheless continued to fire off salvoes against the establishment. A lifelong socialist, he would meet Lenin and Stalin — and Roosevelt too. A broadcast adaptation of The War of the Worlds in America in 1938 would send a whole nation diving for cover. Nothing would ever quite equal the thrill of those pivotal late-Victorian years in Surrey, but as Wells himself put it: "We were 'getting on.' At first it was very exciting, and then it became less marvellous" (Experiment, 543). A larger life was opening up for him, along with the new historical era.

Sources

Beresford, J. D. H. G. Wells London: Nisbet & Co., 1915. Internet Archive. Contributed by Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 13 January 2016.

Draper, Michael. H. G. Wells (Macmillan Modern Novelists series). London: Macmillan, 1987.

Gunn, James. "The Man Who Invented Tomorrow." Gunn Centre, University of Kansas. Web. 13 January 2016.

Hammond, J. R., ed. H. G. Wells: Interviews and Recollections. London: Macmillan, 1980.

_____. A Preface to H. G. Wells. London: Routledge, 2004.

Hopkins, Robert Thurston. H. G. Wells: Personality, Character, Topography. New York: Dutton, n.d. Contributed by Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 13 January 2016.

Mackenzie, Norman & Jeanne. The Time Traveller: The Life of H. G. Wells. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1973.

Parrinder, Patrick. Introduction. H. G. Wells: The Critical Heritage. Ed. Parrinder. Paperback ed. London: Routledge, 2013: 1-31.

Richardson, Dorothy M. The Tunnel. London: Duckworth, 1919. Internet Archive. Contributed by Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 13 January 2016.

Wagar, W. Warren. H. G. Wells: Traversing Time. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2004.

Wells, H. G. Ann Veronica. London: Penguin Classics, 2005.

_____. Experiment in Autobiography: Discoveries and Conclusions of a Very Ordinary Brain (Since 1866). Philadelphia and New York: J. B. Lippincott, 1967. Project Gutenberg. Produced by Chuck Greif & the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net. Web. 12 January 2016.

West, Anthony. H .G. Wells: Aspects of a Life. London: Hutchinson, 1984.

Created 17 January 2016