An earlier version of this review appeared in the Times Literary Supplement of 26 July 2019, under the title, "Transnational Flows." [Click on all the images to enlarge them, and, except the first right, for more information about them.]

When Commodore Matthew Perry sailed into Edo Bay in 1853, a new world opened to both the East and the West. In Quaint, Exquisite, Grace Lavery explores the impact of the encounter, usefully contextualising the later nineteenth-century "cult of Japan": she focuses on intercultural productions as disparate as Gilbert and Sullivan's Mikado and Whistler's Little White Girl on the one hand, and the lifetime's work of Japanese Ruskin enthusiast Ryuzo Mikimoto on the other. These individual studies are illuminating, because Lavery deploys a variety of theoretical tools, and supports her larger findings with research into often unconventional nineteenth-century sources.

Phoney Japaneseness: F. Federici (1850-88) as the Mikado.

Misunderstandings were rife. The Japan of the Mikado, the subject of Lavery's first chapter, is far from authentic. Yet its phony "Japaneseness" is essential to it, she argues, situating it on the margins of British aestheticism. One effect of the "queer realism" that she finds in it was tragic (37). The Mikado's decree that "All who flirted, leered or winked / (Unless connubially linked), / Should forthwith be beheaded" (qtd. p. 43) pointed the way to MP Henri Labouchère's legal intervention of 1885. Passed less than five months after the production opened, Labouchère's amendment criminalised any kind of sexual activity between men, and led to Oscar Wilde's successful prosecution.

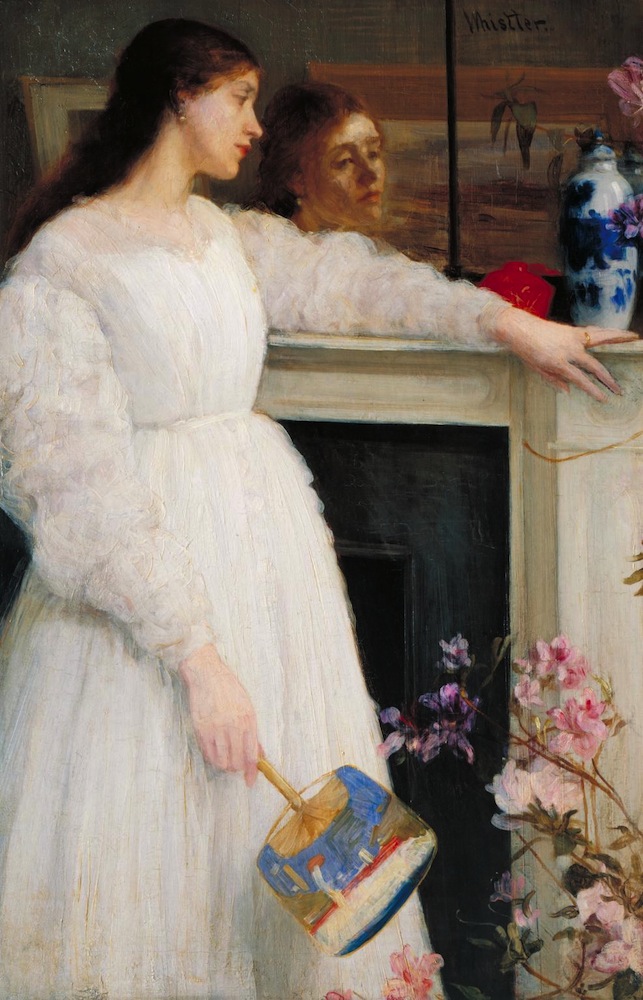

Lavery deals with that "Blue and White Young Man" in her next chapter, along with W. E. Henley, Whistler and others associated with British aestheticism. Here too, "transnational affective flows" (xiii) snagged on Victorian habits of mind. The Little White Girl, featuring a Japanese fan and vase, was one of Whistler's key paintings, but it was not allowed to speak for itself. The artist commissioned Swinburne to write verses to accompany it — verses which, Lavery suggests, intervened between the artwork and the viewer. In a later chapter, Lavery looks askance at Yeats, whose treatment of Japanese culture affects her much as it once affected W. H. Auden. His memorable verdict was, "[Yeats's] mediums, spells, the Mysterious Orient — how embarrassing" (qtd. p. 110).

Left: Whistler's The Little White Girl (1864). Right: Mortimer Menpes's Butterflies (1901).

But Lavery's interests go beyond these familiar figures. She has much to say, for instance, about Mortimer Menpes, who left his "Master" Whistler to see and experience Japan for himself. Wilde, she notes, felt Menpes gained little from his trip. "All he saw," said Wilde, and "all he had the chance of painting, were a few lanterns and some fans. He was quite unable to discover the inhabitants, as his delightful exhibition at Messrs Dowdeswell’s Gallery showed only too well. He did not know that the Japanese people are, as I have said, simply a mode of style, an exquisite fancy of art” (qtd. p. 60). To Wilde, and to the aesthetic sensibility in the west generally, Japan was an idea, an abstraction. Embodying it was impossible for the visitor, who only skated on its surface:actually to embody it would involve some kind of contradiction, even a kind of existential threat to the identity.

Nevertheless, there was this "transnational flow," the word given by Lavery to a certain recipcrocity of influence. In the same (third) chapter, "The Pre-Raphaelite Haiku," Lavery points out that the Japanese poet Yone Noguchi composed his first haikus in English in 1903, ten years before Pound's influential "In the Station of the Metro." More significantly, she finds the genesis of one of the poems ("My Love's lengthened hair") in Rossetti's poem "The Blessed Damozel" as well as in his paintings at the Tate.

In her next chapter, too, Lavery looks at the Japanese side of this "flow." Entitled "Loving John Ruskin," this chapter focuses on Ryuzo Mikimoto, the Japanese enthusiast who collected, translated and wrote about Ruskin's works. Mikimoto's Ruskin Library in Tokyo still funds an annual memorial lecture in his name at the University of Lancaster. Born several years after Ruskin died, Mikimoto nevertheless considered his relationship with the Victorian sage to be one of "intimate friendship" as well as "discipleship" (136). However, Lavery has not set out to make sport of either misconception or over-enthusiasm, but to look for the reasons behind them. "Quaint" in her title refers to such early "attachments" in an interrogatory rather than derogatory way, while "exquisite," which she sees as her book's "main aesthetic category," suggests "the idea of Japan when it is figured aesthetically" (31).

Ryuzo Mikimoto lecturing on Ruskin at Kyobashi Library, Tokyo on 29 March 1935.

Not everyone responded positively to Japanese art: both Walter Crane and William Morris were wary of it, the latter worrying that it indeed posed a threat to the grounded, characterful variety of British workmanship. And there was another, more important, reason to be wary. For Lavery, the word "exquisite" is especially freighted, carrying a poignant association of beauty with delicacy, and inducing an intensity of feeling so great that it tips into pain. This is very much in tune with the melancholy aspect of the fin de siècle and indeed of aesthetics generally. More disturbingly, she argues, the exquisite artwork might be too extreme in some way and eventually too eccentric — or even, again, dangerous: witness Yone Noguchi's descent into imperialism. In her last chapter, "The Chrysanthemum and the Sword," Lavery sees in Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill a series of symbolic castrations, the main instances of which she enumerates.

Aesthetic theory is challenging. Try as she might Lavery cannot always achieve either precision or clarity: in some of her over-complicated sentences, even the grammar gets lost, not to mention the reader. Here she is, trying to pin down aestheticism itself:

following Foucault's distinction between a “history of ideas” and a “his- tory of thought," I propose to treat the aestheticism of the late nineteenth century as representing the social form of aesthetics itself: that it was through the embodied and socially embedded practices of cultivating beauty that the exquisite limits of aesthetic thinking were formulated as a historical problematic. By this I mean: while British aestheticism’s engagement with Japan plugged into the hole of Kantian subjective universal, by supplying a set of objects immediately, absolutely, and universally legible as beautiful, it also brought painfully close to home the narcissistic threat of the Other Empire. [57]

Yet somehow this struggle to clarify ("By this I mean...") suits her theme, because she sees the cultural phenomena that she examines as themselves unstable, and straining away in different directions. In particular, later on, she worries that the enriching "flows" which she celebrates are now being threatened by nationalistic counter-pressures. Such musings are worlds away from the archival explorations and excavations preoccupying most Victorianists now. But both approaches, hands-on and theoretical, are valid and valuable. At her best, Lavery combines them, most eloquently when reading individual texts. That is rather a rare skill.

Bibliography

Lavery, Grace. Quaint, Exquisite: Victorian Aesthetics and the Idea of Japan. Princrton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2019. 219 pp. Princeton University Press, 2019. 219 pp. ISBN 978 0 691 18362 6. £25.

Created 5 April 2023