Apart from the image of the cover, the illustrations included in this review come from the sources specified, not from the the book itself — although the book does have some helpful charts and illustrations of its own.

Twentieth-century criticism inspired an outpouring of sympathy for the Victorian women who were afflicted by mental illness, and a surge of indignation on their behalf. Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar's analysis of Jane Eyre, in which Mr Rochester's first wife, Bertha Mason, is incarcerated in the attic of Thornfield House, put the spotlight on those whose suffered terribly from the stigma attached to female breakdown. But, as sensation fiction from the same period suggests, and as Amy Milne-Smith confirms in her ground-breaking study, there were almost as many "maniacs in the cellar" as there were "madwomen in the attic" (6).

That the former have had a lower profile in other literary genres, and consequently in criticism, is understandable. A man of that time who proved incapable of exercising his expected authority in public and private spheres had no identity, no purpose: in Milne-Smith's words, "a madman who had lost control of his emotions, his actions, or his intellect was therefore in many ways no longer a man" (2). Even as attitudes and treatments improved during the century, mental affliction in males still led to loss of autonomy and was still linked to inadequacy and degeneracy. With those associations went, often enough, hopelessness and self-disgust on the part of the sufferer, and shame on the part of both the sufferer himself and his family. Sympathy and suppport were in short supply. The best such a man could hope for was to be shielded from the common eye, just as completely as a woman.

Asylum for Criminal Lunatics, Broadmoor, Sandhurst, Berkshire: The Terrace. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection (public domain).

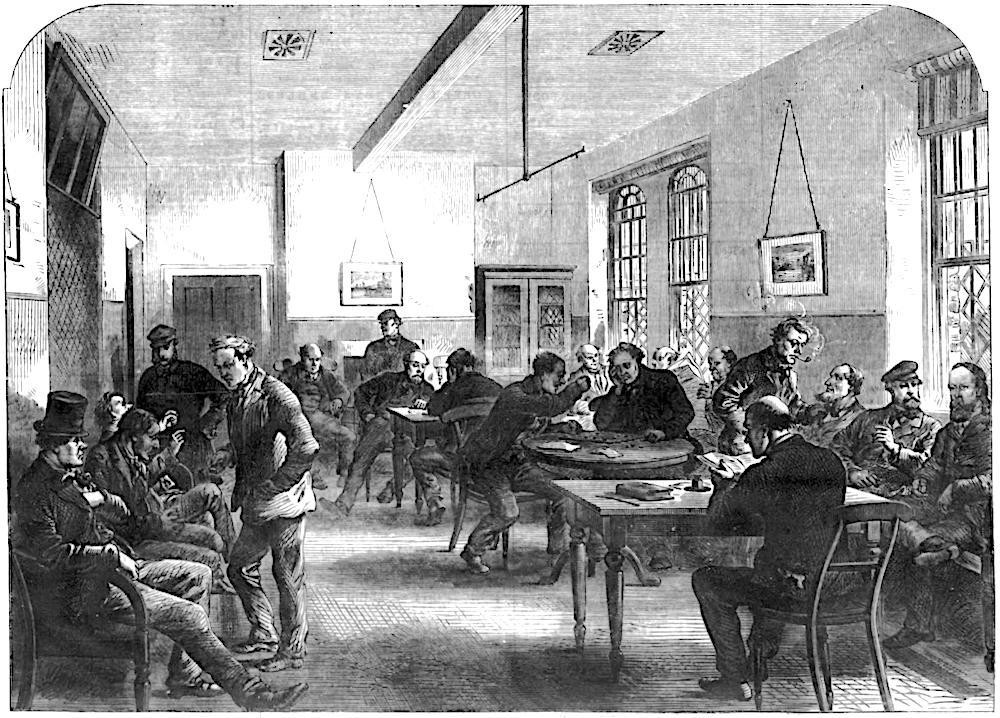

Milne-Smith starts by examining confinement to an asylum, and its profoundly demoralising effect. Perhaps the first big surprise here is the sheer number of both men and women confined in these institutions: "At mid-century there were twelve thousand patients living in asylums as a result of the 1845 Lunatic Asylum and Pauper Lunatics Act, rising to a hundred thousand by 1900" (21). Taking into account criminal asylums such as Broadmoor, opened to male patients in 1864, and military establishments such as the one at Chatham, she finds that not only were there almost as many male as female patients, but that the death rate for men was higher — partly because women's life expectancy was longer anyway, but also because of suicide. Put simply, men "were more likely to successfully end their lives than women" (39). This first chapter is not a history of asylums, as such. For example, the military one at Chatham only gets a passing mention later on, when we learn that a certain Captain Childe, a handsome officer who believed Queen Victoria was in love with him, was threatened with being sent there. There is nothing in this account either about the psychiatric facilities at the Royal Victoria Hospital at Netley, near Southampton, which took in troubled military personnel from 1872. Milne-Smith's purpose here was simply (and usefully) to set the scene for a study of the "representations and experiences of lunacy" that follow (10).

The Asylum for Criminal Lunatics, Broadmoor, Sandhurst, Berkshire: The Day-Room for Male Patients. [Click on this for more about Broadmoor in Victorian times.]

Subsequent chapters present case studies drawn from a variety of sources, from autobiographies to newspaper reports and archival records held at some of the institutions. Chapter 2 deals with those who tried to steer clear of asylums: "Men in the community, home care, doctor's care, and travellers." Home care was not necessarily a matter of selfless service. Some individuals, including, in one instance, a former attendant at Bethlem Hospital in London, exercised a "brisk trade" in providing troubled but as yet uncertified men with lodging and supervision (74). Milnes-Smith gives the simple-minded but harmless Mr Dick in David Copperfield as a fictional example here, noting that he had a small income from which his caregiver, Betsey Trotwood, might have benefited. Mr Dick is treated with good-humoured respect, but of course that was not always the case. In real life, there was a risk that such charges might be taken advantage of, neglected, or abused. On the other hand, caregivers' very lives might be endangered: a certain Captain Andrews, whose family kept him at home despite his violent propensities, eventually battered his wife to death, and was found guilty of "wilful murder" while not being "in control of his actions at the time of the crime" (80). As for men who tried travelling for its curative properties, they too were running risks, and posing them. Some needed to be extricated from difficult situations abroad, and repatriated. A trip to the continent did seem to help John Stuart Mill get over his second breakdown — although he kept quiet about it, suggesting, says Milne-Smith, that "for some men any reduction of their productivity was a story best kept private" (77).

Milne-Smith then looks at the ways in which mental illness could be exacerbated by societal pressures, particularly by the idea that the sufferers were responsible for their own misfortune. Chapter 3, entitled "Personal shame: failures of morality and the will," discusses the way in which a man's loss of mental balance could be put down to addiction, whether to drink, drugs or sex, including the practice of masturbation and the experience of same-sex desire. Seen as the result of sheer self-indulgence, mental collapse in such cases was felt to be culpable. Not being able to continue in a profession or sustain gainful employment was another cause of shame that could lead to despair, seclusion and even suicide — a suicide attempt, in and of itself, being seen as "incontrovertible proof" of madness (159). Although men in these predicaments certainly feature in newspaper reports, they clearly attracted far less sympathy than the "fallen" or abandoned women whose similar fates were depicted in art and fiction alike.

John Edward Gartside (left) and William Hardcastle (right), two patients at the West Riding Lunatic Asylum, Wakefield, Yorkshire. Photographs attributed to James Crichton-Browne (1840-1938), 1872. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection (public domain).

Some men tried to evade committal to an asylum or private care not by travelling or trying to do away with themselves, but by fighting for their freedom. Their fates too could be pitiable. The last case in Chapter 4, about "Madmen at large," is that of George Gilbert Scott, son of Sir George Gilbert Scott. He was an architect himself, and the father of another renowned architect, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott. After an early breakdown, he struggled hard to maintain his practice, only to end up dying as an alcoholic in one of his father's most iconic buildings: the Midland Grand Hotel fronting St Pancras Station in London.

Naturally, such cases captured public attention, and Milne-Smith's next chapter (Chapter 5) deals with "Media panics: stories of violence, danger, and men out of control." The "bestial madman," often but not exclusively from the lower classes, became as common a trope in nineteenth-century newspapers as the vulnerable and victimised woman was in its fiction, but obviously provoked very different reactions. These ranged from anxiety about personal safety to fears that the offender's propensities could be transmitted to his children; and from mistrust of any possibility of a cure, to a sense that the whole race was degenerating. When Franz von Rigals daughter was found to be "masturbating excessively" (250), for instance, the problem was blamed on her father's perversion and the girl was institutionalised.

Milne-Smith holds our attention throughout as she tells an important story of misunderstood and mistreated classes of afflictions. The sixth and last chapter, "Degeneration and madness, inheritance, neurasthenia, criminals, and GPI" leads on very naturally from the previous one, and cases like that of von Rigals and his daughter, while also preparing us for the Epilogue, which explores the ways in which attitudes towards these conditions not only lingered on into the twentieth century, but had dreadful repercussions within it. Concerns about degeneration led ultimately to eugenics, while the search for solutions in individual cases led to "horrific psychosurgeries"(266). Against this background it is easy to appreciate the difficulties men have traditionally had in admitting to, and seeking help for, mental health problems.

Inevitably, there is still much to be said on this subject. As for Victorian notables, John Stuart Mill was only one of those who suffered mental health problems. Others include John Ruskin (in his last years), who does get a brief mention; and three who don't, but spent some time in asylums: the poet John Clare, the architect A.W.N. Pugin, and the artist Richard Dadd. Their cases would all benefit from being explored in this context. Similarly, various issues in these concluding chapters could usefully be brought to bear on late Victorian literature — particularly the appearance of literary doubles, like Robert Louis Stevenson's Jekyll and Hyde, representing two sides of one male persona. The very fact that Milne-Smith's discussions call to mind the lives of these well-known figures, and seem so relevant to the fiction of the time, validates her findings, opening attractive avenues for future research.

Links to Related Material

- The Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum

- Issues of Victorian Masculinity

- Victorian Sciences and Pseudo-Sciences of the Mind (sitemap)

- Ruskin's Madness

- Nicholas Tromans' Richard Dadd: The Artist and the Asylum (review)

- The Victorian Ideal: Male Characters in Jane Eyre and Villette

- Victorian Suicides: Mad Crimes and Sad Histories (a Victorian Web book)

- The Fiend Breaks Loose: "Shadows," Doubles and Demons in London-based Fiction of the Late Nineteenth-century

- Victorian Masculinity: A Selected Bibliography

- Victorian Theories of Biology and Gender: A Bibliography

Bibliography

Milne-Smith, Amy. Out of His Mind: Masculinity and Mental Illness in Victorian Britain. Pbk ed. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2022. £25.00. xi + 311 pp. ISBN: 978-1-5261-7885-5

Created 28 June 2024