The following essay was written for Professor Béatrice Laurent’s seminar, "Myths and Icons in Victorian Britain,"" English 2MIAM25, Université Bordeaux-Montaigne, 2023.

Andromeda: The Origins

Greek mythology’s quintessential damsel in distress, the maiden chained to a rock waiting to be saved by the half-naked hero à la grecque who arrives on his winged horse engulfed by lustrous light, Andromeda is a trope of Victorian art that originates in the myth of Perseus. Early mentions of Andromeda and Perseus appear in Hesiod’s Catalogue of Women as well as in Ovid’s famous retelling of the story in his Metamorphoses, and in Apollodorus’s Library, a collection of Greek myths and legends from the first or second century AD.

Here is a précis of the myth, according to Apollodorus’s Library:

Being come to Ethiopia, of which Cepheus was king, he [Perseus] found the king's daughter Andromeda set out to be the prey of a sea monster. For Cassiepea, the wife of Cepheus, vied with the Nereids in beauty and boasted to be better than them all; hence the Nereids were angry, and Poseidon, sharing their wrath, sent a flood and a monster to invade the land. But Ammon having predicted deliverance from the calamity if Cassiepea's daughter Andromeda were exposed as a prey to the monster, Cepheus was compelled by the Ethiopians to do it, and he bound his daughter to a rock. When Perseus beheld her, he loved her and promised Cepheus that he would kill the monster, if he would give him the rescued damsel to wife. These terms having been sworn to, Perseus withstood and slew the monster and released Andromeda. (Book II, 159-161)

Of the several themes present in the myth of Perseus and Andromeda, most notable is the heroism embodied by Perseus, the male saviour who serves as an example of bravery and chivalry. Although Andromeda is selected to atone for her mother’s prideful insult to the Nereids, in the end she is saved by Perseus. The myth culminates in marriage, as Perseus asks Andromeda’s parents for her hand in marriage before saving her. Andromeda’s beauty is also a major element of the myth, as it is the reason Perseus is drawn to her; centuries later, her beauty will be the vehicle that carries the myth into Victorian art.

But there is more to the Victorian Andromeda than the passive role she plays in the original myth. Representations of Andromeda in Victorian Britain, notably in poems and paintings, allow for a re-reading of Andromeda in which she has a new identity that expands beyond the constricting chains of victimhood. Her sacrifice for her people, her fortitude in accepting to be sacrificed, and her resilience in the face of danger are heroic attributes that place her on her own heroic pedestal. Andromeda may thus be recast as a hero in her own right, an equal to Perseus.

The Revival of Andromeda in Victorian Britain

Under Queen Victoria’s reign, Britain witnessed unparalleled progress and expansion. Many artists of the time rejected this new industrial Britain and took it upon themselves to revive the beauty and romance of the Renaissance and the Middle Ages. From this endeavour emerged a fascination with ancient mythology that led to a wealth of reproductions in prose, poetry, painting, and sculpture. Nonetheless one cannot help but wonder: Why use the medium of the myth in particular? According to Walter Burkert, myths "characterize the human, the world, and the universe. Therefore, they contain important information about the traditions and beliefs of a society" (qtd. in Akkaya, 278). Conversely, can myth also be used to create, or at least revive, traditions and beliefs within a society? The answer would seem to be yes, as Erich Neumann in Amor and Psyche (1971) asserts that “myth is always the unconscious representation of [...] crucial life situations” (45).

Whether consciously or unconsciously, Victorian artists revived myths not only in order to return to a more aesthetically pleasing time but also to shape the principles of their society. The Victorian age witnessed an increased interest in Andromeda, as evinced by the plethora of literary and iconographic depictions of her. There were two observable peaks of interest in the myth, one in 1854 and another in 1889. [1] The first was a year after the onset of the Crimean War, and the second was the year of the founding of the Women’s Franchise League, a political organisation that campaigned for women’s voting rights in local elections. Showing the heroic acts of Perseus and his fearlessness could be a seen as an encouragement for Victorian men to take up arms and fight, while depicting Andromeda as the Victorian model of womanhood could be society’s response to the rise of the women’s movement and their fight to break free from their chains. These two events may have spurred a revival of the myth of Perseus and Andromeda.

An Antidote to the New Woman

The Victorian era was one of duality and paradox. Nina Auerbach, in Woman and the Demon: The Life of Victorian Myth (1982), describes its social structure as "sharply divided" in several ways: wealth versus poverty, evolution versus degeneration, the traditional woman versus the New Woman. "Clean-minded Victorians," she writes, considered the good woman as "existing only as daughter, wife, and mother," along the lines of Coventry Patmore's model of the 'angel in the house' who devotes herself to her family (4). On the one hand, women like Sarah Ellis, a widely-read Victorian anti-feminist writer, abided by this traditional representation. In The Women of England (1845) she considered that "the women of England are deteriorating in their moral character, and that false notions of refinement are rendering them less influential, less useful, and less happy than they were." These women were thought to be “neglecting their domestic duties” in search of professional avenues that were still largely inaccessible, activities that led, on the other hand, to the rise of a new kind of Victorian woman (15-17). These women, who were criticized as exhibiting a "deterioration" in moral character, were independent, educated, and uninterested in marriage, children, and a life spent in the service of others. In the words of scholar Greg Buzewell, they exemplified "the New Woman who threatened conventional ideas about ideal Victorian womanhood."

And so, Victorian society deemed it necessary to put the woman in her place, in ways that were subtler than those put forth in the work of Sarah Ellis or in Mrs. Octavius Friere [Emily] Owen’s The Heroines of Domestic Life (1861); like other similar works, these books imparted the message that a woman's place is in the home. These subtle repressions, crystallised in poems, paintings, and sculptures that retold myths and resurrected icons, seemed to double as cautionary tales. One way to dispirit women surfing this surge of feminine power was to remind them, through the mythical icon of Andromeda, of their perpetual state of vulnerability and their need for a male saviour to free them from the physical and mental shackles that had been, paradoxically, imposed upon them by none other than the men in their lives.

In his poem Andromeda (1858), the priest, novelist, and poet Charles Kingsley (1819-1875) describes the scene that led Andromeda to her enchainment on the rock, her long wait in her chains, and her rescue by Perseus. The following passage describes Andromeda’s pleading with the Sun god as she writhes under the scorching heat, asking for his pity and for a much more merciful death:

Dost thou not pity me, Sun, though thy wild dark sister be ruthless;

Dost thou not pity me here, as thou seest me desolate, weary,

Sickened with shame and despair, like a kid torn young from its mother?

What if my beauty insult thee, then blight it: but me – Oh spare me!

Spare me yet, ere he be here, fierce, tearing, unbearable! See me,

See me, how tender and soft, and thus helpless! See how I shudder,

Fancying only my doom. Wilt thou shine thus bright, when it takes me?

Are there no deaths save this, great Sun? No fiery arrow,

Lightning, or deep-mouthed wave? Why thus? What music in shrieking,

Pleasure in warm live limbs torn slowly? (p. 31)

Kingsley's language — his use of words like "pity," "desolate," "weary," "despair," "tender and soft," and "helpless" — amplifies Andromeda's weakness and her victimhood. Interestingly Kingsley also has Andromeda repeatedly mention her shame. Why should she, atoning for her mother's mistake and therefore not guilty of any crime, feel ashamed about her situation? Was shame yet another means to an end — to put a woman in her place?

The emphasised fragility in Kingsley's poem is visually reflected in William Etty's Andromeda, Perseus Coming to Her Rescue (1840). In this painting, Andromeda stands in the foreground with the sea monster at her feet. She throws her head back in agony while her exposed body, with her feet crossed at the bottom, accentuates her vulnerability. In Andromeda's Chains: Gender and Interpretation in Victorian Literature and Art (1989), Adrienne Munich notes that "the pose recalls Renaissance and Baroque depictions of martyrdom, the eyes seeking deliverance from a higher authority" (45). This representation of Andromeda, like most — if not all — Victorian depictions of Andromeda, includes her naked body, a similarly awkward stance, flowing hair and fabric, and eyes either turned upward, as in Edward Poynter’s Andromeda (1869), to denote pleading, or downward, as in John Bell’s sculpture, Andromeda (1851), to denote submission, along with the slightly parted lips. These elements evoke the beauty, sensuality, and eroticism of the fragile feminine, and benefit the male gaze. Interestingly, Kingsley revived Andromeda not only in his poem but also in a children’s story appearing in his book The Heroes (1879), where he goes a step further by adding an element that cannot be found in any other reproduction of the myth, and that is blood. In his story, Andromeda states that "nothing but my blood can atone for a sin which I never committed" (51). The use of the blood, an important symbol relating to the feminine and the female body, and one relating to sacrifice, is quite telling, particularly that the target audience of this story is young girls, as well as boys.

William Etty, Andromeda, Perseus Coming to Her Rescue (1840). Courtesy of the Royal Albert Museum and Art Gallery. Click the image to enlarge it.

A Reaffirmation of Gender Roles

At a time when Britain was experiencing a crisis of faith incurred by the rise of science, the myth of Andromeda was used to bolster, in Auerbach's words, "three cherished Victorian institutions: the family, the patriarchal state, and God the Father" (1). On the flip side of industrialisation and expansion, there was, according to Patricia McCallum, a "sense of a hostile and anxiety-ridden world which gave the Victorian myth of the feminine its particular force. Isolated in the home, and therefore protected from the menace of the external world, the woman was to nurture and shelter her husband and children, [to be] a haven in a heartless world" (43-44). Artists and public alike seemed greatly concerned with "the clean delineation of gender equations," as noted by Laura Claridge in her review of Munich’s Andromeda’s Chains; and Munich herself has noted the "sentimentalisation of marriage" occurring just as "middle-class women began to imagine other choices" (35). William Morris provided stellar guidance on the matter in his epic poem The Earthly Paradise (1875), in which he presented a reimagined romance to the Victorian men and women through heroic quest and romantic love crowned by marriage. And what better example of romance than the myth of Perseus and Andromeda? Morris describes the moment Perseus first laid eyes on Andromeda:

Naked, except for tresses of her hair

That o'er her white limbs by the breeze were wound,

And brazen chains her weary arms that bound

Unto the sea-beat overhanging rock,

As though her golden-crowned head to mock.

But nigh her feet upon the sand there lay

Rich raiment that had covered her that day,

Worthy to be the ransom of a king,

Unworthy round such loveliness to cling. (p. 268)

Not only does the verse begin with the vulnerability of Andromeda's "naked" appearance but it also continues by highlighting her weakness along with a suggestive, yet subtle, description of her sensual womanly features. Further down the line, Perseus assumes his protective role by "gently" putting down the maid, who “sank down,” running towards the source of danger, the reason that made Andromeda shiver "in her every limb," to slay the sea monster.

Then Perseus gently put the maid from him,

Who sank down shivering in her every limb,

[...]

As down the beach he ran to meet the foe. (p. 274)

While we are reminded again of Andromeda’s never-ending vulnerability, Perseus's bravery and fearlessness are re-emphasised through the detailed description of the monstrosity ahead. The creature facing him is a "great black fold," no easy opponent. Nestled in its "skull," rather than the more neutral "head," are angry eyes the colour of fire. It is "hideous," a "beast" with "adamant jaws" and "lidless eyes." No matter, for Perseus laughs in the face of danger as he "lightly" leaps aside, unafraid of the creature’s immense size and otherworldly nature evident through its strange "black blood." The words of these verses are graphic for a reason: the greater the danger, the braver the hero.

A great black fold against him did uprear,

Maned with grey tufts of hair, as some old tree

Hung round with moss, in lands where vapours be;

From his bare skull his red eyes glowed like flame,

And from his open mouth a sound there came,

Strident and hideous, that still louder grew

[...]

The adamant jaws and lidless eyes of fire

Did Perseus mock, and lightly leapt aside

As forward did the torture-chamber glide

Of his huge head, and ere the beast could turn,

One moment bright did blue-edged Herpe burn,

The next was quenched in the black flow of blood. (p. 274)

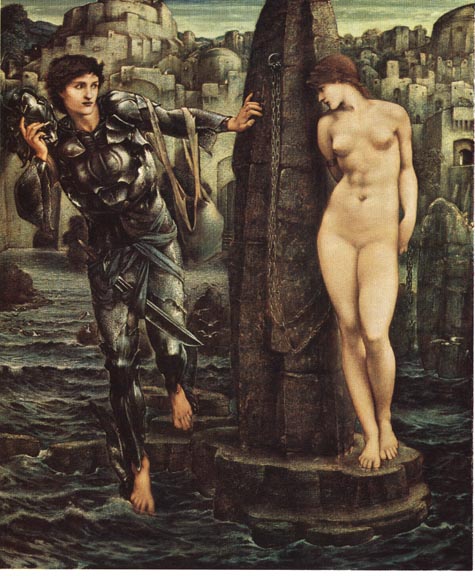

The Earthly Paradise was illustrated by Edward Burne-Jones in The Perseus Series (1875-1888). The two paintings depicting the myth of Andromeda are The Rock of Doom (1885-88) and The Doom Fulfilled (1888). In the first painting, Andromeda seems ashamed, like Andromeda in Kingsley's poem. She almost disappears next to the male hero. Her body's faded features make her look ghostly, while her left breast almost completely disappears in the white glow engulfing her body. Burne-Jones reflects Morris's romanticism through Andromeda's stance. According to Munich, Andromeda here "assumes the pose of the goddess of love," a reference to Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (1485-86), in which Venus stands beside a rock with a distinctly "phallic shape" (123). In the second painting, Andromeda's back is turned to the observer, as if her only means of expression, her face, were taken away from her, while Perseus performs his heroic act. But the darker strokes of the brush contouring her various body parts bring her to life, as if Perseus's heroic act has turned her into a fully-fledged woman.

Left: Edward Burne-Jones, The Rock of Doom (1896). Right: Burne-Jones, The Doom Fulfilled (1896). Both courtesy Staatsgalerie Stuttgart. Click the images to enlarge them.

Andromeda: The Unsung Hero

Victorian representations of Andromeda focus mainly on her virginity and passivity [2]. This comes as no surprise as the Victorian myth of Andromeda has repeatedly been revisited from a predominantly masculine perspective: bravery and chivalry are qualities Perseus displays when he rescues the sacrificed daughter, the helpless damsel in distress, while other themes that are part of the original myth are played down, notably Andromeda’s heroism and self-sacrifice. However, scholars such as Munich, Constance W. Hassett, and Lee Edwards have re-interpreted Andromeda's role to highlight its heroic facets. As Munich confirms in her study of Andromeda in Victorian art, “Andromeda’s plight was powerful in itself, without reference to Perseus” (25). Indeed, Andromeda saved an entire people, the people of Aetheopia, by accepting to be sacrificed in the most brutal and cruel way: naked, chained to a rock, in the cold, the heat, and the water, waiting for the sea monster to devour her exposed flesh. But these representations remain, ultimately, images. If we were to apply to these images the conclusion Susan Sontag proposes in On Photography (1973), we may claim, following Sontag, that they have “multiple meanings” and that just like photographs, paintings "are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy" (23).

Recent research has opened the way to new perceptions of the hero, the heroic, and heroism. These terms have traditionally lacked definitive meanings, despite the centuries-long fascination with heroism as a concept. Broadly speaking, hero status can be achieved through the demonstration of attributes such as sacrifice and resilience. Andromeda, an undeniable example of sacrifice, and particularly self-sacrifice, was offered as scapegoat to appease the wrath of the sea-god. She withstood this mentally and physically traumatic event with resilience. In Frederic Leighton’s Perseus and Andromeda (1891), Andromeda is a half-naked figure with a cascade of white cloth covering her lower half, with her head leaning exaggeratedly to the side, a stance that is reminiscent of one of the many symbols of self-sacrifice in Abrahamic religions, and particularly Christianity: Jesus Christ.

In Edward Poynter’s Andromeda (1869), she stands tall, alone front and centre, defying the elements with the softness of her naked body. She neither yields nor falls to the ground out of exhaustion. The blue drapery forming an arch over her head brings to mind another resilient figure: the Virgin Mary. The violent movement of the waves reminds us that Andromeda’s time on the rock was no picnic, that she endured violence. The research on heroism shows a strong correlation between heroism and violence. The violence emanating from the act of sacrifice, and which Andromeda suffered on that rock of doom, elevates her to a status of sacredness according to a symbolic process that René Girard articulated years ago in Violence and the Sacred (1972). More recent psychological theorists have noted that heroism is at the core of human experience, while subject-matter experts Philip Zimbardo and Zeno Franco posit that heroism is not exclusive to an elite minority; according to Zimbardo’s notion of the banality of heroism, anyone can become a hero. [3]

Left: Frederic Leighton, Perseus and Andromeda (1891). Courtesy of the Walker Art Gallery, National Museums Liverpool. Right: Edward Poynter, Andromeda (1869). Courtesy Pérez Simón Collection, Mexico. Click the images to enlarge them.

According to Elaine Showalter, "passing as limp and ineffectual" is a "concealment of real strength and purpose," a point that we have already made about Victorian representations of Andromeda. But modern research suggests that even Andromeda’s passivity cannot be regarded as such. On this view, she gave herself up to submissiveness as an "act of will"; the will, which, in Victorian mainstream thinking, according to John R. Reed in Victorian Will "may be defined as man’s capacity to put himself at one with some transcendent law" (197; qtd in Gray, p. 45). By acceding, in the service of another, to a law that extended beyond her person, Andromeda acted according to a will that was not her own. According to Franco, a person behaving in this way "may be declared a hero by one or more onlookers," and subsequently become a hero.

The many interpretative possibilities allow us to reimagine Andromeda as the hero, rather than the victim. Constance W. Hassett asserts that "the roles of Perseus and Andromeda are by no means mutually exclusive. A defenceless innocent may create her own saviour, and the strong saviour may be the morally needier of the two" (45). One study, by Lee Edwards, of another mythical figure, Psyche, offers ample grounds upon which one might claim that Andromeda is a similarly powerful figure, and that she, in her own way, is also a hero. For his theoretical framework Edwards relies upon Erich Neumann, a scholar and Jungian analyst, who in his study of the myth of Psyche identifies "heroism as a recurring pattern of human action" and by identifying this pattern he shapes “the particular psychological traits of any single heroic figure” (qtd. in Edwards, p 38). According to Neumann, female heroism does exist. However, in Andromeda’s case, it is her inaction, as opposed to Psyche’s action, that makes her a hero. Therefore, the focus here is not on Neumann’s definition of heroism, but on his complex methodology which allows the inclusion of "the personal and the social," as Edwards puts it, in the identification of a hero.

Edwards follows Neumann, who concludes that physical action alone does not make a hero. Neumann sees that the heroic act exists to support an underlying growth of consciousness, that it does not exist "for its own sake" but is a "symbolic expression of underlying psychic structures" (40). In other words, heroism is without a doubt in the action, but the action is not only a demonstration of physical capacities, but also of mental capacities and power. Is it possible to actually believe that Andromeda, in her calm submission to her brutal fate, is not in fact showing undisclosed signs of immense mental strength? Edwards argues that Psyche’s physical actions have a parallel in the actions of classic male heroes (38); similarly Andromeda’s willingness to be led, like a lamb to the slaughter, to atone for someone else’s sin, has a parallel in the sacrifice of Jesus Christ, nailed to the cross, and she exhibits similar mental and physical endurance of extremely harsh conditions for the sake of her people. Her passivity becomes an act of heroism.

Andromeda is a hero by human standards, and not merely feminine ones. According to Edwards, Neumann’s analysis revolves mostly on proving that Psyche is a female hero and not a hero, full stop. To remedy this, Edwards relies on the work of anthropologist Victor W. Turner who "assumes the existence of patterns of interaction common to all societies and characteristic of human beings as species." He posits that Psyche is a hero and not only a female hero because she goes through "un rite de passage," a process that is not exclusively masculine. This process consists of three phases: "separation, margin (or limen, signifying 'threshold' in Latin), and aggregation" (48). Put simply, a before, during, and after of a particular event that incurs an individual’s growth. This process can be applied to Andromeda who, in the first phase is separated from a prior "set of cultural conditions," namely she is taken from her home and place as the princess of Aetheopia, goes through a "liminal" period in which she is chained to a rock and left waiting, and finally returns to a relatively stable state. This makes Andromeda a "liminar" or, to use Turner’s word, a "threshold" figure, a typically "passive or humble" figure who "regardless of sex" acquiesces to "arbitrary punishment without complaint." Edwards confirms that Turner’s "liminar" is Neumann’s hero, and thus, by this logic, that Andromeda is not only a literary heroine but also a hero in her own right.

Conclusion

Many works of Victorian art focusing on Andromeda are not incorporated in this paper. These include two poems by Robert Browning, Pauline (1868) and The Ring and The Book (1868-9), both of which use the myth of Andromeda as a pattern, further etching this icon into Victorian consciousness; as well as a play by James Robinson Planché and Charles Dance titled The Deep Deep Sea, Or, Perseus and Andromeda: An Original Mythological, Aquatic, Equestrian Burletta in One Act (1840), which contributes to the democratisation of mythology, with Andromeda becoming a possible model for the women of the suffragette movement who, in later years, chained themselves in protest, using this act of static inaction as a tool to make their voices heard. These Victorian Andromedas — and many others, particularly iconographic Andromedas — were illustrated beautifully, calling attention first and foremost to the exposed female form in all its sensual glory. What seemed like an escape or a diversion from a depressing reality clearly doubled as a Trojan horse, carrying within itself a model of what Victorian society ought to be. Whether Andromeda and her representations succeeded in fulfilling this purpose lies beyond the scope of this research. However, it has provided ample grounds for new readings and analyses of Victorian gender roles and to gender more broadly, to its study and interpretation. Nevertheless, more effort should be directed towards affirming heroism not as a gendered attribute but as a human characteristic. Despite the many years that separate us from the Victorian era, the Andromeda woman is alive and well. However, it is up to us to choose how we see vulnerability, to decide whether we are to interpret a fragile character as a hero or a victim.

Notes

[1] Google Books Ngram Viewer. Search term and parameters: Andromeda, 1837-1901.

[2] See, for example, reviews of Munich's Andromeda's Chains by Laura Claridge and Lynn Alexander.

[3] See the discussion in Zeno, et al.

Links to Related Material

- Chivalry and the Psychology of Love in Edward Burne-Jones's Perseus and Andromeda

- Andromeda ‐ Women in Chains

- Mythological Subjects in Victorian Painting

Bibliography

Akkaya, Burcu. "A Psychomythological Syndrome: The Andromeda Complex in Occupational Life and its Dimensions." Journal of Qualitative Research in Education (2023): 276-299.

Alexander, Lynn. "Review of Andromeda’s Chains: Gender and Interpretation in Victorian Literature and Art and Gendered Interventions: Narrative Discourse in the Victorian Novel." Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 10, no. 1 (1991): 151–153.

Apollodorus. The Library. Trans. James George Frazer (London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1921).

Auerbach, Nina. Woman and the Demon: The Life of a Victorian Myth. (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard UP, 1982).

Bresson, Anne. "Victorian England: Birthplace of Fantasy." Bibliothèque nationale française. https://fantasy.bnf.fr/en/understand/victorian-england-birthplace- fantasy/

Buzwell, Greg. "Daughters of decadence: the New Woman in the Victorian fin de siècle." (The British Library, 2014). https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/daughters-of- decadence-the-new-woman-in-the-victorian-fin-de-siecle

Chaliakopoulos, Antonis. "Andromeda: The Legendary Princess of Greek Mythology." The Collector (2021). https://www.thecollector.com/andromeda-mythology-greek-perseus/

Cheney, Liana De Girolami. "Edward Burne-Jones' Andromeda: Transformation of Historical and Mythological Sources." Artibus et Historiae 25, no. 49 (2004): 197–227.

Claridge, Laura. “Review of The Private Lives of Victorian Women: Autobiography in Nineteenth-Century England by A. A. Munich and V. Sanders." The Modern Language Review 87, no. 3 (1992): 711–713.

Powell, Véronique Gérard. Désirs et Volupté à l'èpoque victorienne — Collection Pèrez Simon. Connaissance des arts, Hors-Série, no. 593 (Brussels: Fonds Mercator, 2013).

Edwards, Lee R. "The Labors of Psyche: Toward a Theory of Female Heroism." Critical Inquiry 6, no. 1 (1979): 33–49.

Ekall, Patricia Y. "Andromeda: Forgotten Woman of Greek Mythology." Art UK, August, 17 2021. http://artuk.org/discover/stories/andromeda-forgotten-woman-of-greek-mythology.

Ellis, Sarah Stickney. The Women of England: Their Social Duties and Domestic Habits. (London: Fisher, Son, & Co., 1845).

Franco, Zeno E., et al. "Heroism Research: A Review of Theories, Methods, Challenges, and Trends." Journal of Humanistic Psychology 58, no. 4 (2016): 382-96.

Girard, René. Violence and the Sacred. Trans. Patrick Gregory. (London: The Athlone Press, 1995).

Gray, Erik. "Getting It Wrong in The Lady of Shalott." Victorian Poetry 47, no. 1 (2009): 45–59.

Hall, Edith. "Classical Mythology in the Victorian Popular Theatre." International Journal of the Classical Tradition 5, no. 3 (1999): 336–66.

Hassett, Constance W. The Elusive Self in the Poetry of Robert Browning. (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1982).

Kaizer, Ted. "Interpretations of the Myth of Andromeda at Iope." Syria 88 (2011): 323–339.

Kingsley, Charles. Andromeda and Other Poems. (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1858).

—. The Heroes or Greek Fairy Tales for My Children. (London: Macmillan & Co., 1879).

Kyriakakis-Maloney, Stella. The Resuscitation of Romance: William Morris's The Earthly Paradise. PhD diss., York University, 1994.

Maurer, Oscar. "Morris's Treatment of Greek Legend in The Earthly Paradise." The University of Texas Studies in English 33 (1954): 103–118.

McCallum, Pamela. "Review of The Victorian Girl and the Feminine Ideal by D. Gorham." Newsletter of the Victorian Studies Association of Western Canada 9, no. 1 (1983): 43–44.

Morris, William. "The Doom of King Acrisius." The Earthly Paradise. (London: Ellis & White, 1873).

Munich, Adrienne. Andromeda’s Chains: Gender and Interpretation in Victorian Literature and Art. (New York: Columbia UP, 1989).

Nicholes, Joseph. "The Virgin to the Rescue: Robert Browning’s Inversion of the Myth of Perseus and Andromeda." Studies in Browning and His Circle 16 (1988): 18–29.

Planché, James Robinson and Dance, Charles. The Deep Deep Sea, Or, Perseus and Andromeda: An Original Mythological, Aquatic, Equestrian Burletta in One Act. (London: T.H. Lacy, 1857).

Reed, John R. Victorian Will. (Athens, Ohio: Ohio UP, 1989).

Sawhney, Paramvir. " Chivalry and the Psychology of Love in Edward Burne-Jones's Perseus and Andromeda." The Victorian Web, 2006.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1973.

Created 8 November 2024