Introduction

he word "gambling" was not used widely in the English language until the eighteenth century. It was derived from the Anglo-Saxon word gamen, meaning "sport, pleasure joy or pastime" (Ashton 2). Gambling became widespread among all classes of society from the late eighteenth century. Although enormously popular during the Regency period and the Victorian era, gambling was publicly scorned as a moral evil because it produced godlessness, induced dishonesty and demoralization, and destroyed the moral fabric of society. A number of prominent public figures, including priests, writers and politicians condemned gambling, which was initially endemic among the upper classes, but gradually affected the lower classes. Parliament enacted several legislations to curb the practice of public gambling, but they were of little use. Gambling in a variety of forms continued to flourish until the very end of the Victorian era and, subsequently, in the twentieth century, and to date.

Parliament legislation

Men gambling in a casino or gaming club, an aquatint of about 1810-1819 Wellcome Collection, ref. 33371i (public domain).

Upper-class gamblers, who used to have more leisure time, preferred to play for money safely in isolation among their social peers in exclusive private clubs, which emerged in big cities, out of which London offered by far the best gambling environment. All classes gambled with cards and dice, however the elite clubs allowed for more table games like hazard (an old dice game, mentioned in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales and roulette. During the first half of the nineteenth century, attitudes toward gambling and betting were officially negative. In 1823, the Lotteries Act made private lotteries illegal and in 1826 government lotteries were abolished, although, unlike betting and gambling, which were intended to yield purely private profit, many lotteries were apparently designed for the public good. In 1844, the House of Lords Select Committee on Gaming was established. It recommended stronger police action against gambling dens. The Gaming Act of 1845 was passed to discourage betting, but it did not make it illegal. Its principal goal was to deem a wager unenforceable as a legal contract. In 1853, Parliament passed the Betting Houses Act to suppress betting shops, and prohibited cash betting everywhere except at racing enclosures and private clubs. This act did not do much either, as most betting activities merely switched clandestinely to the street. From 1890, premises had to be licenced for gambling. The Street Betting Act of 1906 provided that any person found frequenting or loitering in streets or public places for the purposes of bookmaking or betting or wagering would be guilty of a criminal offence and would be subject to penalty, ranging from a maximum £10 fine for a first offence to a £50 fine or imprisonment for a maximum of six months with hard labour for a third. Until the 1880s, gambling and betting in England were almost exclusively popular among the upper classes, but in the last two decades of the century they also attracted the working classes.

Gambling and betting as a serious moral and social problem

Gambling and betting became endemic in the Regency period and in the Victorian era continued to expand in various forms despite vigorous public condemnation and legal restrictions. Great fortunes were lost at the gaming tables by compulsive gamblers from the upper classes. The Anglican and Nonconformist Protestant Churches as well as the Catholic Church in England led campaigns against gambling and betting through preachers, press articles and booklets. Churches also condemned the association of many sports with gambling. With little regard to such appeals, aristocratic men gambled at horse races and played cards at high stakes in the gentlemen's clubs of Pall Mall and St James's in London. Likewise upper-class ladies often played for lower stakes such popular card games as loo, macao, whist and rouge-et-noir. The anti-gambling campaigners were particularly dismayed by the number of lower-class gambling men and women. When in 1903, Lord Dawey presented his Betting Bill to the House of Lords, he argued that betting was widespread among both men and women of the lower classes, although the latter bet less often because their household budget left little extra for such diversions (McIntire 355). Increasingly through the nineteenth century social reformers, left-wing and socialist thinkers vigorously campaigned against gambling in England with more than modest effect. In these cases, concern was rather to protect the poor from their own folly and the exploitation of the gambling entrepreneurs. This was behind the formation of the National Anti-gambling League (NAGL) in 1890, founded in order to eliminate all forms of public gambling including horse-racing, which became its major target of attack (Munting 1998, 630). Samuel Smiles (1812–1904), an author and social reformer, criticised gambling and betting in his popular books Self Help (1859) and Thrift (1875). In 1905, Benjamin Seebohm Rowntree (1871–1954), a social reformer, industrialist and philanthropist, published a book, Betting and Gambling: a National Evil, which considered the gambling habit as a socially harmful pastime and a source of social and economic problems. In spite of condemnation and warnings, towards the end of the nineteenth century drinking, gambling and betting also became a favourite part of working-class culture.

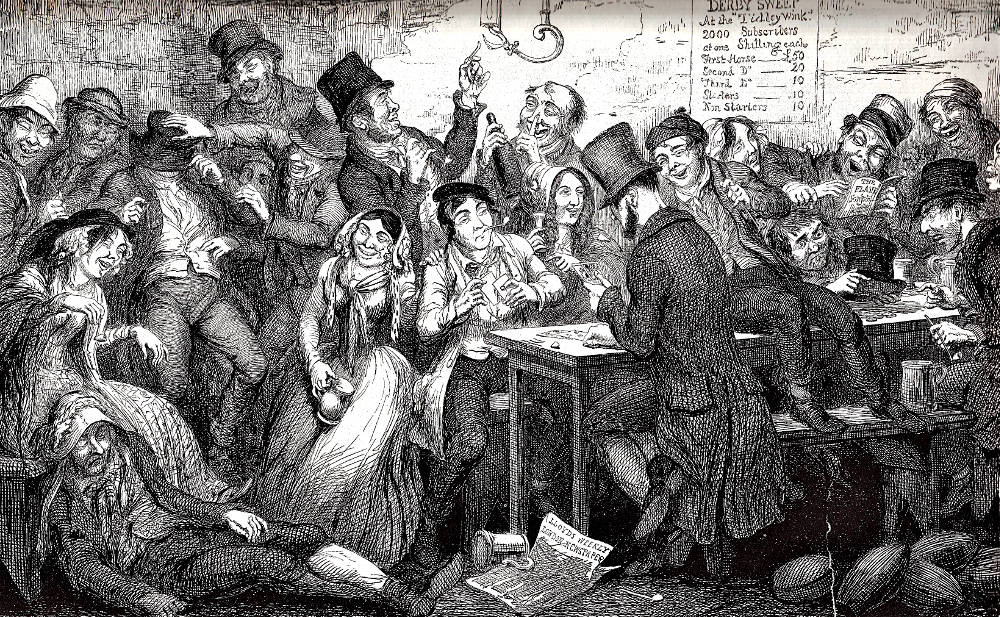

George Cruikshank's depiction of a betting parlour, in his book, The Drunkard's Children, of 1846. [Click on the image for more information.]

The gambling and betting industry began to flourish towards the end of the Victorian era due, amongst others, to the commercialization of sport. This new style of gambling and betting was based almost exclusively upon horse racing (Itzkowitz 8). The railway revolutionized horse racing and horse-racing gambling. Horses could be sent by rail, as could owners and spectators. Although horse-race betting became the dominant part of late Victorian gambling practice, many other forms of gambling flourished. Dog racing, also called greyhound racing, was popular from the second half of the nineteenth century until the mid-twentieth century. The most popular gambling game of skill and chance among the lower classes was pitch-and-toss. It was played by tossing a coin and calling heads or tails. Hazard played for money with dice, not only had a long history, but would be the ancestor of the modern game called craps. Whist was one of the most popular gentleman's card games and a precursor to the modern game of bridge. Baccarat, a card game of chance rather than skill, became very popular among the upper classes in the last decades of the nineteenth century.

Gambling houses and compulsive gamblers

Two types of gambling clubs emerged in the Regency and Victorian eras: "Golden Hells" for the wealthy and "Copper Hells" for the poorer clientele. In the early nineteenth century, St James's in the West End was the most notorious gambling street in London. Five most infamous gentlemen's clubs, White's, Watier's, Brooks's, Boodle's and Crockford's, all situated in St James's Street, offered gambling services, mostly cards, which were usually played for high stakes. White's, originally a chocolate shop, moved to 37-38 St. James in 1778, and became a favourite place of gambling for influential Tories in the Regency period. William Crockford (1776–1844), a skilled bookmaker and one of the wealthiest self-made men in England, opened in 1828 in London's fashionable St. James's Street the most infamous gambling club known as Crockford's. Its members were the cream of society. Gambling houses, often called 'hells', were regarded as temples of ruin, indolence and guile (Rendell 78). In the 1890s the existence of gambling hells in London was notorious.

Frontispiece of William Jesse's The Life of George Brummel, esq, commonly called Beau Brummell, Vol.I.

There were numerous cases of compulsive gamblers who lost money and their estates due to unrestrained gambling habits. The famous "Beau" Brummell (1778–1840), an undisputed arbiter of men's fashion during the Regency period, in one night alone lost over £5,000 at Gordon's gambling club in Jermyn Street, London. He had to flee to France to avoid debt imprisonment. George Osbaldeston (1786–1866), nicknamed the Squire, a brilliant horseman, and a compulsive gambler, lost on horses some £200,000 (equivalent to over £2 million today). Eventually, he had to sell his estates and died almost penniless. Sir Vincent Hynde Cotton (1801–1863), a cavalry officer and sportsman, lost his estate through gambling and eventually was forced to work as a coachman (Mingay 146). Lord Byron's lifelong friend from Cambridge, Scrope Davies (1782–1852), a famous dandy and an inveterate gambler, played cards in Watier's, Brooks' and other London clubs for high stakes. In 1814, he won over £6000 at Watier's at macao. He lent Byron about £5000 to pay for his Eastern Tour. Eventually, Davies's gambling habits ruined him and he fled the country in 1820 to avoid creditors. Lord Byron's daughter, Ada, Countess of Lovelace (1815–1852), a talented mathematician, also described as the world's first computer programmer, was also a compulsive gambler. Beginning in the 1840s, Lovelace began a gambling habit that forced her to secretly pawn some of her jewels. Ada lost £3,200 betting on the wrong horse at the Epsom Derby. Queen Victoria's eldest son, the future King Edward VII, who had a reputation as a debonaire playboy prince, was also a notorious gambler. He was fond of horse racing and playing cards, especially the game of baccarat. In 1891, he was involved in the Royal baccarat scandal that ended up in his appearance as a witness in a courtroom.

Betting

Betting can be considered a type of gambling, but there is one notable difference between gambling and betting: the former entirely relies on luck while the latter depends on skill, strategy, and luck. Thus betting is an attempt to win by predicting the outcome of a betted event, whereas gambling depends on chance alone. Betting was rampant by the middle of the nineteenth century, and there were around 150 betting houses that accepted bets from the working class of London. By the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, betting was still popular among the lower classes. Bookies were able to use telegraphic results, so workers all over the country could make many bets in a single day. In 1902, the House of Lords Select Committee on Betting argued that: "Betting is generally prevalent in the United Kingdom, and that the practice of betting has increased considerably of late years especially amongst the working classes" (McKibbin 149). In 1906, the government introduced the Street Betting Act that tried to stop betting practice. It was not successful as most bets were small, and police were not trying to stop the practice. Before 1914 mass betting was devoted almost exclusively to horses (McKibbin 147). The new form of betting which appeared in the 1880s involved the emergence of professional bookmakers who charged between six pence and one shilling for a variety of bets, of which horse-racing was most popular. The most important race venues were Derby at Epsom, the Thousand Guineas at Newmarket and St. Leger at Doncaster. Football betting was less widespread and dog-race betting was unimportant until the mid 1920s (McKibbin 147). Obscure betting shops could be found in almost every town. These places operated alone or in conjunction with some other trade, such as tobacconist or shoemaker. Apart from these lowly places there were betting venues operating for the rich, such as Tattersall's and Goodwood. Gambling went hand in hand with race meets occurring at Newmarket, Ascot, Doncaster, Epsom, Warwick, Windsor and practically every other course throughout England (Hughes 143).

Gambling in Regency and Victorian fiction

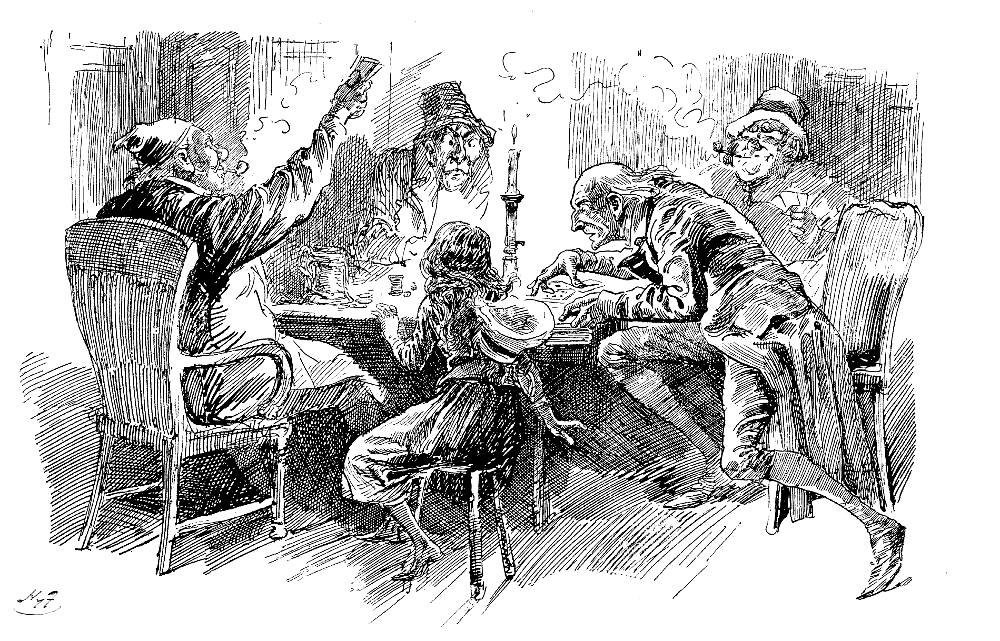

Little Nell's grandfather playing cards in Harry Furniss's illustration for The Old Curiosity Shop. [Click on the image for more information.]

The phenomenon of gambling became a widespread motif in the literature of the Regency and Victorian times. Several authors, such as Benjamin Disraeli, Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray, George Eliot and Anthony Trollope, perceived gambling as a serious social problem. The protagonist of Disraeli's novel, The Young Duke (1831), George Augustus Frederic, Duke of St James, is an orphan, who has inherited an enormous fortune. Refusing to follow the advice and guidance of his good guardian, Mr Dacre, a Catholic and a former friend of his father's, the young Duke becomes an unprincipled dandy who wastes much of his wealth on luxuries, debauchery and gambling. The Duke's gambling reaches its height when he loses £100,000 at écarté during a virtually continuous forty-eight hour game. In Coningsby (1844), gambling is shown as a parasitic aristocratic pastime. Sybil (1845), opens with a description of the idle aristocratic youths gambling on horse races in the eve of the Derby of 1837. In Tancred (1847), gambling is exposed as a feature of aristocratic degeneracy. In Charles Dickens's Old Curiosity Shop (1840-41), Little Nell's grandfather becomes strongly addicted to a gambling habit and although he loses all his possessions, including the curiosity shop, he cannot overcome his addiction, hoping in vain that he will eventually win a fortune for his granddaughter. In Thackeray's Vanity Fair (1847-48) people are particularly obsessed with money associated with vice and gambling. The main female protagonist, Becky Sharp, drinks heavily and gambles. Becky's vain aristocratic husband, Rawdon Crawley, is very good at cards and billiards, and the selfish George Osborne, Amelia's unfaithful husband, is 'excellent in all games of skill.' The title hero of Pendennis (1848-50) is also involved with gambling. Gambling, particularly on sporting events, pervades the novel. Contrary to the previous authors, George Eliot sincerely despised gambling (Flavin 125). In Middlemarch (1870-71), gambling emerges as a significant social problem. Most gambling happens in the billiard room at the Green Dragon. Gambling is also a major issue in Eliot's last novel, Daniel Deronda (1876). Much of Anthony Trollope's The Way We Live Now (1875) centres on gambling and fraudulent machinations in the railway business. The title heroine in George Moore's Esther Waters (1894) is brought up in the Woodview estate where the prevalent type of gambling is horse racing.

Conclusion

Gambling was a favourite pastime for many members of the upper classes in the Regency and Victorian eras. Up to the mid-nineteenth century, gambling in England was mostly associated with the intemperance of decadent members of the upper classes. In spite of several anti-gambling laws, in the next decades it affected increasingly the working-classes and turned into a serious social problem. Excessive gambling and betting affected relationships, physical and mental health, work performance, social and family life, and was often a cause of the financial ruination of individuals. In the final quarter of the nneteenthth century, when Britain began to lose its economic supremacy, gambling was described as a 'national evil' which was predicted to be harmful to both individuals and state. In spite of this, today the UK can boast of one of the biggest gambling markets in the world.

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

Ashton, John.The History of Gambling in England. Project Gutenberg. First pub., 1898.

Bailey, Peter. Leisure and Class in Victorian England: Rational Recreation and the Contest of Control, 1830-1885. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978.

Chinn, C. Better Betting with a Decent Feller: Bookmaking, Betting and the British Working Class 1750-1990. London, 1991.

Clapson, Mark. A Bit of Flutter: Popular Gambling and English Society, c. 1823-1961. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992.

Dixon, David. From Prohibition to Regulation: Bookmaking, Anti-Gambling, and the Law. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991.

Flavin, Michael. Gambling in the Nineteenth-Century English Novel: "A leprosy is o'er the Land". Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2003.

Hogge, J. M. The Facts of Gambling. London, 1907).

Hughes, Kristine, The Writer's Guide to Everyday Life in Regency and Victorian England from 1811-1901. Cincinnati, OH: Writer's Digest Books, 1998.

Itzkowitz, David C. "Victorian Bookmakers and Their Customers." Victorian Studies. Vol. 32, no.1 (Autumn 1988): 6–30.

Jesse, William. The Life of George Brummel, esq, commonly called Beau Brummell. Vol. I. New York: Scribner, 1886. Internet Archive, from a copy in Cornell University Library.

Marcus, Julia. Lady Byron and Her Daughters. New York, London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2015.

McKibbin, Ross. "Working-Class Gambling in Britain 1880-1939." Past & Present 82 (1979): 147-178.

McIntire, Matthew. Odds, "Intelligence, and Prophecies: Racing News in the Penny Press, 1855-1914." Victorian Periodicals Review. Vol. 41. no. 4 (Winter 2008): 352-373.

Milne-Smith, Amy. London Clubland: A Cultural History of Gender and Class in Late Victorian Britain. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Mingay, G.E. A Social History of the English Countryside. London: Routledge, 2013.

Munting, R. An Economic and Social History of Gambling in Britain and the USA. Manchester, 1996.

___. "The Revival of Lotteries in Britain: Some International Comparisons of Public Policy." History. Vol. 83. No. 272 (October 1998): 628-645.

Perkins, E. Benson. Gambling in English Life. 1950.

Raven, James. "The Abolition of the English State Lotteries." The Historical Journal. Vol. 34. No. 2 (June 1991): 371-389.

Rendell, Jane. Pursuit of Pleasure: Gender, Space and Architecture in Regency London. London: The Athlone Press, 2002.

Rowntree, B. Seebohm, ed. Betting and Gambling: A National Evil. London: Macmillan & Co. London; New York: The Macmillan Co., 1905.

Vamplew, Wray. The Turf: A Social and Economic History of Horse Racing. 1976.

Weare, W. The Fatal Effects of Gambling Exemplified in the Murder of William Weare. London: T. Kelly, 1824.

Wykes, Alan. Gambling. London: Aldus Books, 1964.

Last modified 25 June 2014