Portraits of Palmerston by John Partridge (1845) and by the photographer Mayall later in his career. Click on images to enlarge them.

Henry John Temple, Viscount Palmerston, twice served as Prime Minister: 6 February 1855 to 19 February 1858 and 12 June 1859 to 18 October 1865. The eldest child of Henry Temple and Mary Mee in a family of two boys and three girls was born in Park Street Westminster on 20 October 1784. The family owned estates in County Sligo and County Dublin in Ireland as well as their Hampshire property. Palmerston was educated privately by a series of tutors before attending Harrow between 1795 and 1800. Thereafter he was admitted to Edinburgh University where he studied between 1800 and 1803, moving to St. John's College Cambridge in 1803 where he was awarded his MA in 1806. When Palmerston's father died in 1802, the young man was left under the guardianship of the Earls of Malmesbury and Chichester until he came of age; on the death of Pitt the Younger in 1806, he stood as the Tory candidate for the Cambridge University by-election and came in third. It was not until his fourth electoral attempt that he was finally returned as an MP, for Newport on the isle of Wight. The seat was the property of Sir Leonard Holmes who made it a condition of the seat that Palmerston should never go there. In 1811 Palmerston finally was returned as MP for Cambridge University.

In 1809 the PM, the Duke of Portland resigned and was replaced by Spencer Perceval who offered Palmerston the post of Chancellor of the Exchequer: he refused on the grounds of lack of experience but accepted the post of Secretary at War that did not carry Cabinet position; he held this post right through Lord Liverpool's ministry until Wellington formed his ministry in 1828 and was the beginning of Palmerston's contact with the army and foreign affairs.

It was well known that Palmerston had affairs with Lady Jersey and Princess Dorothy de Lieven before he began his affair with Lady Cowper in 1810; when her husband died in 1839, the pair finally married. Lady Cowper was the sister of Lord Melbourne, who said that his sister was a 'remarkable woman, a devoted mother, and excellent wife — but not chaste'. Despite the affair with Emily, Palmerston made proposals of marriage to Lady Georgiana Fane, the younger sister of Lady Jersey: his suit was rejected on all three occasions.

In 1813 Palmerston spoke in the Commons in favour of Catholic Emancipation, and after the Battle of Waterloo he suggested that any soldier who had fought in the battle should be allowed to count it as two years' service for pay and pensions purposes. This increased the cost of the army at a time when complaints were being made about the lack of economies being made by reducing the army at the end of the French Wars. Palmerston's attitude was that the army had to be kept in a state of readiness because of its now-increased responsibilities in maintaining peace in Europe as well as the British colonies. On 1 April 1818 Palmerston was shot and wounded by Lieutenant Davis, an ex-officer who had a grievance over his pension: officers were reduced to half-pay unless they were on active service. Palmerston financed Davis' defence out of his own pocket and ensured that the man was well looked-after when he was sent to Bedlam. However, in 1822 Charles Smith was not so fortunate: he was caught poaching on Palmerston's estates and was executed. Palmerston refused to intervene on the grounds that it was not right to use private influence to affect the due process of law.

Palmerston was determined to reduce the expenditure of the War Office and produced plans to cut the cost of administration by £18,000; the following year — 1822 — he was offered the post of Governor General of India, which he refused. It was not long afterwards that he began to take a more direct interest in foreign affairs, speaking on the Franco-Spanish problems that had recently arisen.

In August 1827 George Canning promised that Palmerston should have the post of Chancellor of the Exchequer; he refused because he did not want to have to pay the cost of standing for re-election although he did agree to accept the post in the new parliamentary session. However, the king objected to Palmerston's appointment, and Canning offered him the Governorship of Jamaica followed by the Governor General-ship of India, both of which Palmerston refused. After the death of Canning, Palmerston joined Wellington's government but resigned shortly afterwards in the quarrel over the redistribution of seats from disenfranchised rotten boroughs: at that point he left the Tories and joined the Canningites in parliament: they soon joined the Whigs and Palmerston was a Whig for the remainder of his very long parliamentary career.

In November 1830 Earl Grey formed his ministry and Palmerston was appointed as Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, holding the post until 1841; during this time he

- acted as chairman at an international conference that debated the Belgian question following the Belgian revolt against Dutch rule. The problems were solved when Leopold of Saxe-Coburg became the first King of the Belgians

- tried to intervene in the Italian revolts to stop Austria and France becoming involved in the affairs of Naples and the Papal States (1831)

- set up the Quadruple Alliance between Britain and France to support the liberal regimes in Spain and Portugal

- tried to exclude French influence from Iberia on the grounds that this could be against British interests

- saw the successful conclusion of the Opium Wars with China and insisted on very harsh terms including the legalisation of the opium trade. The Treaty of Nanking was concluded after he left office. Hong Kong was ceded to Britain by this treaty: Palmerston described it as 'a barren island with barely a house upon it'.

- brought about (for Britain) a successful conclusion to the most recent manifestation of the 'Eastern Question' by concluding the Treaty of London in 1840. His attitude, as expressed in a letter to John Hobhouse, was prophetic:

It seems pretty clear that, sooner or later, the Cossack and the Seypoy, the man from the Baltic and he from the British Isles will meet in the centre of Asia. It should be our business to take care that the meeting should take place as far off from our Indian possessions as may be convenient and advantageous to us. But the meeting will not be avoided by our staying at home to receive the visit.

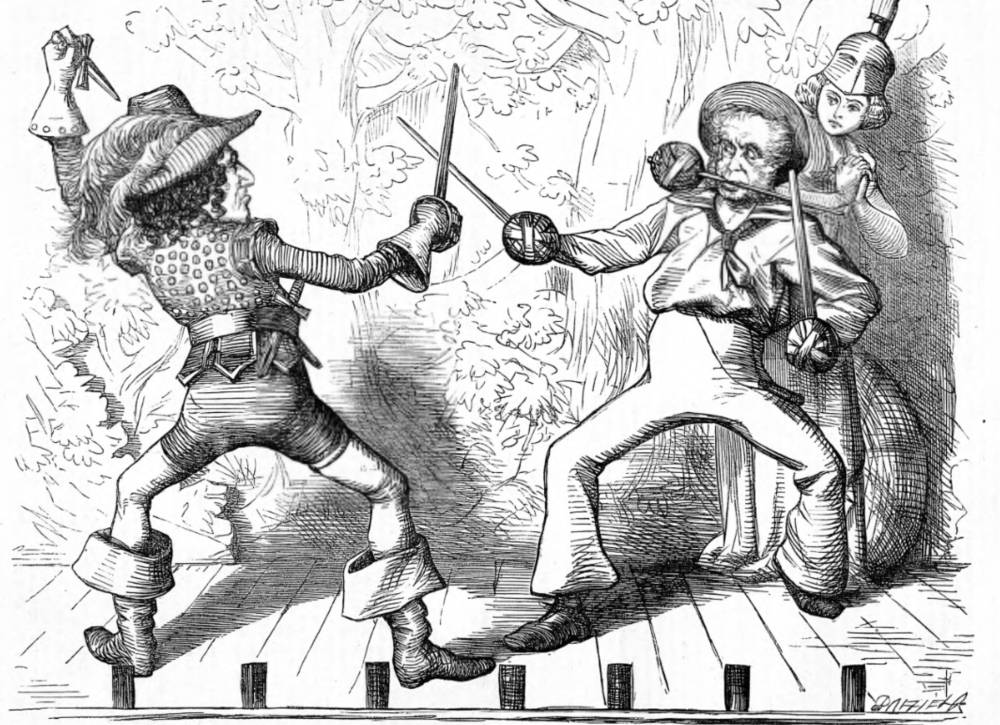

Three cartoons from Fun featuring Palmerston: Left: A Lesson in Dip-lomacy. Middle: The Battle of Hustings. Right: In Training for St. Stephen’s.

In 1841 Lord Melbourne resigned and was replaced as PM by Sir Robert Peel: for the first time in many years, Palmerston was able to spend time on his favourite occupations of riding, hunting and racing. He continued to attack the government's foreign policy that was in the hands of the Earl of Aberdeen; in 1844 Palmerston made a three-hour speech denouncing the slave trade, for example. He returned to the Foreign Office in July 1846 following the establishment of Lord John Russell's ministry. Almost immediately, the Portuguese queen, Maria, asked Palmerston for help in crushing a revolt by liberal elements in the country; the Constitution was restored as the liberals wished but Maria remained in power.

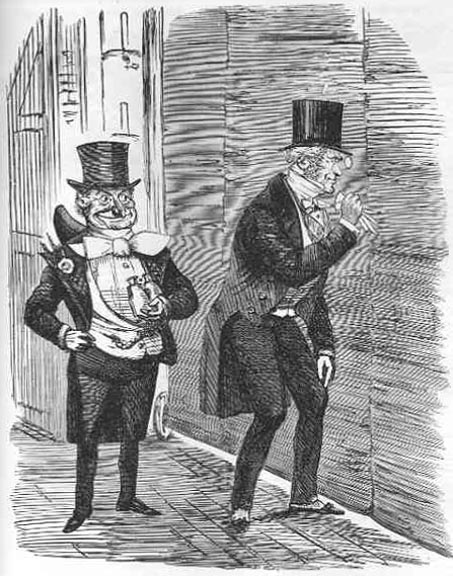

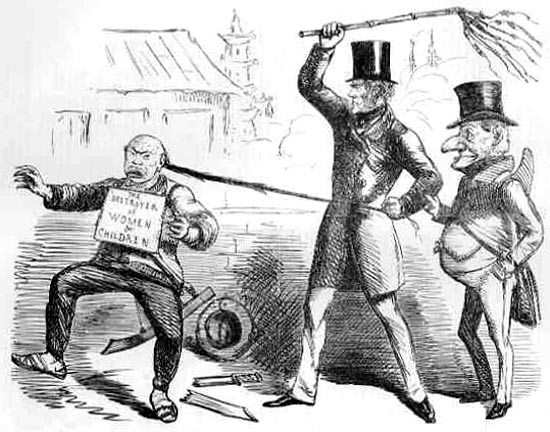

Three cartoons from Punch featuring Palmerston: Left: The Last Pantomime of the Season. Middle: Behind the Scenes. Right: A Lesson to John Chinamen.

During the Irish Famine of the 1840s Palmerston's actions were less than humanitarian towards his tenants. Mr. Ferrie, a member of the Legislative Council of Canada, reported that the majority of Irish emigrants in 1847 had been sent out by their landlords in a state of 'utter destitution and misery': they had been persuaded to emigrate by promises which had not been fulfilled. A thousand people had been shipped off by Lord Palmerston's agents, who promised them clothes and from £2 to £5 a family on their arrival at Quebec. When they arrived they 'were in a state of fearful destitution'. Ferrie said, 'the last cargo of human beings which was received from Lord Palmerston's estate was by the Lord Ashburton'. Of these emigrants

87 were almost in a state of nudity; the food provided on board the ship was of the worst description; that the ship was excessively overcrowded; that no sufficient vigilance was exercised in this respect by the agents at the outports; and that the whole mortality had been upwards of 25 per cent of the number embarked'.

Palmerston's land agent denied the allegations but the estates were depopulated during the Famine years and subsequent 'land improvements' were carried out.

1848 saw a spate of revolutions across Europe and Palmerston was gratified to see many of his old rivals, such as Metternich in Austria, being removed from power. In 1850 he overstepped the bounds of acceptability with the Don Pacifico incident although his attitude towards British subjects was applauded in Britain. It was over this event that he made his 'Civis Romanus Sum' speech, stating:

As the Roman, in days of old, held himself free from indignity when he could say 'Civis Romanus Sum' [I am a Roman citizen], so also a British subject in whatever land he may be, shall feel confident that the watchful eye and the strong arm of England will protect him against injustice and wrong.

The following year, Russell dismissed Palmerston for recognising Louis Napoleon Bonaparte's regime in France: the political nation was delighted at Palmerston's downfall although his popularity in the country meant that there was widespread outrage at his removal from power. Palmerston was determined to have his 'tit for tat with little Johnny Russell'; in his anger he went to his home at Broadlands rather than go to Buckingham Palace to return his seals of office to Queen Victoria when required to do so. Two months later, in February 1852, Russell resigned after the defeat of his government at the hands of Palmerston; the Earl of Derby formed a ministry that lasted only until the end of the year. It was replaced by Aberdeen's ministry in which Palmerston was Home Secretary even though his forte was foreign affairs. In his new role, in 1853 he was responsible for

- a Factory Act

- a Smoke Abatement Act in London

- the Penal Servitude Act that stopped transportation to Tasmania (Van Diemen's Land)

Broadlands, Hampshire: the home of Lord Palmerston. Starting in 1767, the house was virtually rebuilt . Originally it had been part of the property of Romsey Abbey but had been sold off at the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

In March 1854 the Crimean War broke out; it was mis-handled by Aberdeen who was obliged to resign because of his government's shortcomings; the Queen was forced to appoint Palmerston as PM after failing to find anyone who would accept the post. Palmerston agreed to the Committee of Enquiry, precipitating the resignations of Gladstone, Sir James Graham and Sidney Herbert. The war was brought to a conclusion on February 1856 although there was no real settlement of the difficulties that had caused it in the first place.

Having terminated one war, Palmerston then supported Bowling, the Governor of Hong Kong, who had ordered the bombardment of Canton in retaliation for the the Chinese authorities' seizure of the Arrow, a British registered ship. Palmerston was censured by parliament for his action; he called a general election and won a huge majority. In 1857 the Indian Mutiny broke out. The Governor General, Lord Canning was accused of being too lenient but he had Palmerston's support: when the mutiny ended, public reaction favoured the leniency. Palmerston followed up these events with the Government of India Bill that transferred power from the East India Company to the British government. He resigned in February 1858; a year later he was one of the founding members of the Liberal Party that was formed at Willis' Rooms. The 274 members came from a broad spectrum of political opinion and included men such as Palmerston, Russell and John Bright. Shortly afterwards, Queen Victoria invited Palmerston to form another ministry in the absence of alternative candidates for the post.

In August 1860, an Anglo-French expedition marched on Peking to force the Emperor to comply with the 1842 Treaty of Nanking: the Summer Palace was burned down during the conflict but Palmerston's attitude was that it would 'bring John Chinaman to his bearings'. During the American Civil War (1861-5) the PM maintained Britain's neutrality but still allowed shipyards to supply vessels to the Confederate states and he was prepared to go to war with America over the Trent incident. He also supported Denmark over ownership of Schleswig-Holstein but did not intervene when Prussia invaded in February 1864. Palmerston said later that only three people ever understood the Schleswig-Holstein Question: the Prince Consort, who was dead, a clerk at the Foreign Office who went mad, and himself-and he had forgotten.

Palmerston always had a reputation as a "ladies' man": indeed, one of his nicknames was 'Lord Cupid'. In 1863, Mrs. O'Kane visited him at the House of Commons and then later claimed that she and Palmerston had committed adultery. Her husband, a radical journalist, promptly cited Palmerston as co-respondent in a divorce case and claimed £20,000 in damages. The case was dismissed but increased Palmerston's popularity: he was 78 years old.

In 1865, following a vote of censure, Palmerston called a general election which he won with a convincing majority; however, he did not see the new parliament convened because he died of a fever on 18 October 1865 after catching a chill while out in his carriage. He wanted to be buried at Romsey Abbey but was given a state funeral at Westminster Abbey. Palmerston was 81 years old. It has been said that his last words were, 'Die, my dear doctor? That is the last thing I shall do!"

Related Materials

- A Speech on Foreign Policy — Affairs of Greece (June 25, 1850)

Recommended reading

Ridley, J. Lord Palmerston. London, 1970.

Judd, D. Palmerston. London, 1975. [Review]

Last modified 15 March 2002

Image added 28 June 2020