This review first appeared in the online inter-disciplinary journal Cercles; the original version can be seen online here. It has been reformatted and illustrated for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee, who has also added the links and captions. Thank you to the websites which, like ours, allow reuse of images with attribution. Click on the images for larger pictures, and for more information when available.

Elizabeth Hurren's book on the late-Victorian poor law, like many academic monographs, started life as a PhD thesis. Unlike most volumes in the genre, her work has been reissued in paperback and so has been promised a new and wider readership for her ground-breaking work. Few PhDs can hope to achieve the same impact and longevity.

The case examines the poor law as a component of local government, and as a source of contention in the late-nineteenth century. The established line on the decades 1870-1900 held that the turbulence of the 1830s was well behind the poor law, which had developed into a relatively stable entity nationwide with broadly agreed protocols for policy decision and action. The "crusade" against outdoor poor relief, an attempt to compel paupers to accept workhouse welfare that was at its most potent in the early 1870s, is generally underplayed as a relatively short-lived and geographically-curtailed experiment. Hurren explodes this settled picture by revealing the visceral challenge of the crusade to consensual and humanitarian impulses in some locations. She analyses the turbulence that might be engendered by the clash of prominent local personalities with new county structures, with more diverse electorates, and with emergent rural trades-unionism. Giving the crusade its historiographical due, she argues that it could make a very significant impact on the poor as a mediator of the experience of pauperdom and as a spur to politicisation.

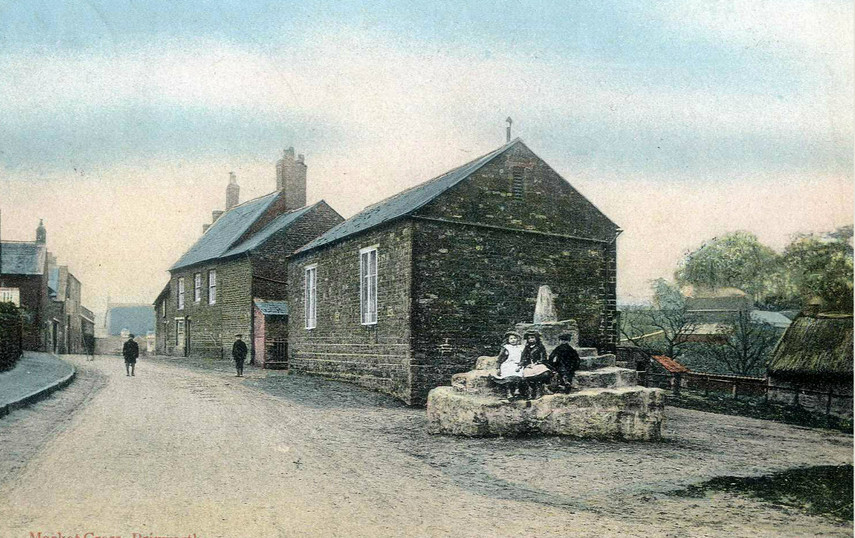

Left to right: (a) Rural Brixworth (historic postcard showing its Market Cross, courtesy of the Brixworth History Society). (b) The former Brixworth Union Workhouse (photograph by Burgess Von Thunen, from the Geograph website). (c) The former North Staffordshire Infirmary, which had a "working-man's contributory scheme" (photograph by Alf Beard, from Wikimedia Commons, slightly modified here).

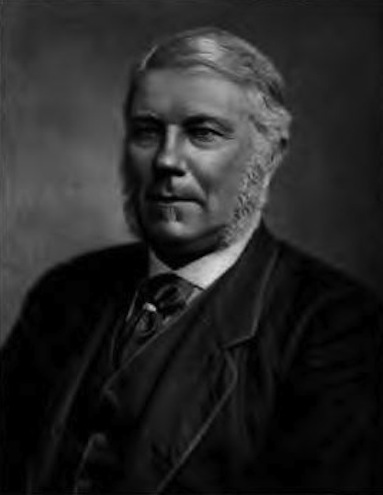

The book focuses on the rural Brixworth Union in Northamptonshire and its rich evidence of administratively-enforced hardship and concomitant protest against the crusade. The ideological complexion of the Union apparently originated in a desire by the third Earl Spencer to control welfare in the vicinity of his Althorp estate. The crusading initiative was developed by the fifth Earl in concert with the Reverend William Bury, but arguably the most potent force behind the local crusade was Albert Pell, a Conservative Member of Parliament for Leicestershire and a Brixworth Guardian. Pell recurs throughout the book as a ruthless Deus ex machina, using every pretext to pare back Union expenditure and promote bracing schemes for reducing pauper dependence. In doing so he wilfully ignored the human cost of his ideology in pauper misery, and may have misrepresented his researches on ventures elsewhere. What he saw in the Staffordshire Potteries, for example, was a working-man's contributory scheme to the North Staffordshire Infirmary which was emphatically not a means for abolishing poor-law medical relief. This did not inhibit Pell from using the Staffordshire model to push for an end to medical relief in Brixworth. Pell's pervasive influence was critically acknowledged in a pamphlet of 1894 which alluded to "the voices of Mr Albert Pell" (emphasis mine).

A "ruthless Deus ex machina": Albert Pell (1820-1907), frontispiece of his Reminiscences (London: John Murray, 1908), from Harvard University's copy in the Internet Archive.

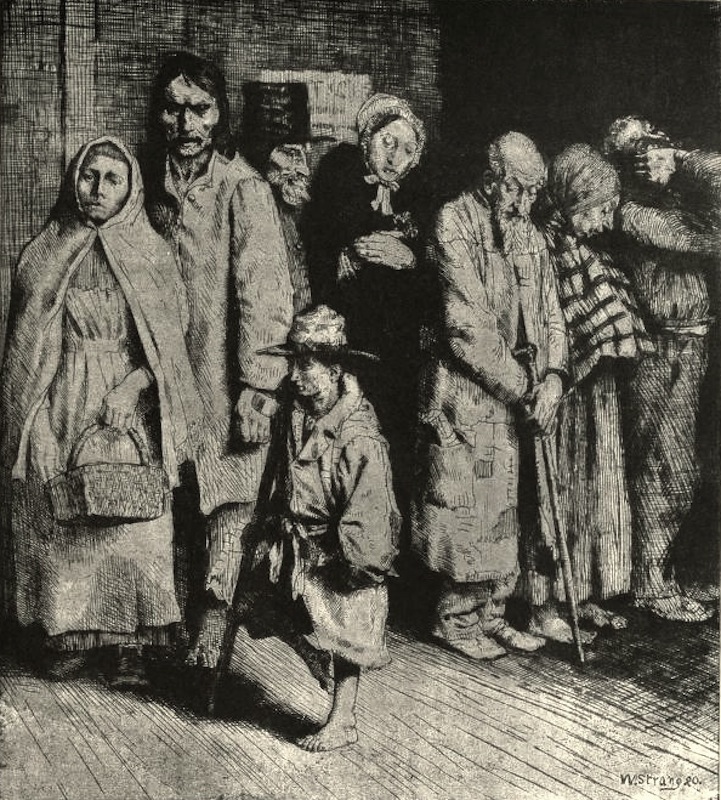

Given the evident sufferings of the Brixworth poor, Protesting About Pauperism is not a comfortable read. Chapter eight, which covers pauper pleas to observe funerary norms and burial arrangements, is unequivocally grisly, given that the alternative to a pauper grave was consignment to dissection within a medical school. Hurren construes the Medical Relief (Disqualification Removal) Act of 1885 as an instrument relatively neglected by historians but offering sly support to committed crusaders. Even so the most insidious development in Brixworth was the "Secret Service Fund" which operated from 1878 until 1896. This was an unofficial scheme, implemented by the leading crusaders on the Board of Guardians with the compliance of the (very highly paid) relieving officer. Every time a deserving case was made for outdoor relief, the officer referred it to a crusading Guardian rather than to the Board. The Guardian then made a discretionary payment from a small charitable fund, run only by core crusaders, on the proviso that the applicant did not reapply for relief. Any pauper brave enough to reapply to the Union regardless was rejected, on the specious grounds that they had already received charity. This insulated the crusading agenda from other Guardians who might have been disposed to generosity, reduced the apparent demand for outdoor relief, and pressurised the poor into making do on time-limited benefits. It was a brutally underhand and manipulative strategy, and it worked very well for the crusaders for a surprisingly long time.

The Cause of the Poor, by William Strang R.A. (1859-1921), 1890.

Stringent crusading was only curtailed by the successful election of opposing and working-class guardians. In Brixworth the balance of power shifted decisively across the 1890s as a coalition of the working and lower-middle classes, from agricultural labourers to small-scale employers, secured a voting majority on the Brixworth Board. One hero of this story is Sidney Ward, a counter-weight to the malign Pell, whose commitment to founding the Brixworth District Outdoor Relief Association exemplified the motives of most members: they had personal connections to those treated severely by the Union. The Association took the opportunity offered by the changes to qualification for voting in 1893 to secure a significant minority among Guardians, and thereafter the opponents of crusade both within and beyond the Association steadily supplanted Pell's party. Ward was elected as a Guardian in 1896, ironically to represent Althorp, and became Chair of the Brixworth Guardians in 1899: "Democracy had triumphed" (239).

Brixworth was undoubtedly an atypical Union in its aggressive, successful and long-lasting implementation of crusading principles, but a close examination of the severity possible under the late-nineteenth-century poor law is a sharp reminder of the discretion open to Guardians before the democratisation of local-government voting. This research may be the most significant intervention in the historiography of the New Poor Law in the last generation. Now its reissue will make the analysis accessible for undergraduate purchase as well as postgraduate and postdoctoral research.

Book under Review

Hurren, Ellizabeth T. Protesting about Pauperism: Poverty, Politics and Poor Relief in Late-Victorian England, 1870-1900. Royal Historical Society Studies in History, New Series. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2015. Paperback reissue (1st ed., 2007). xii + 216pp. £19.99. ISBN 978-0861933297.

Created 17 June 2016