The Oxford and Cambridge Boat-Race was a favourite feature in the The Illustrated London News, as seen (for example) on the cover of the issue of 27 March 1877, shown on the left below. Our founding webmaster, George Landow, had kept some illustrations of the various races in a "to-do" folder, but had never found time to put them all together and write about them. This is an attempt to complete this unfinished work.

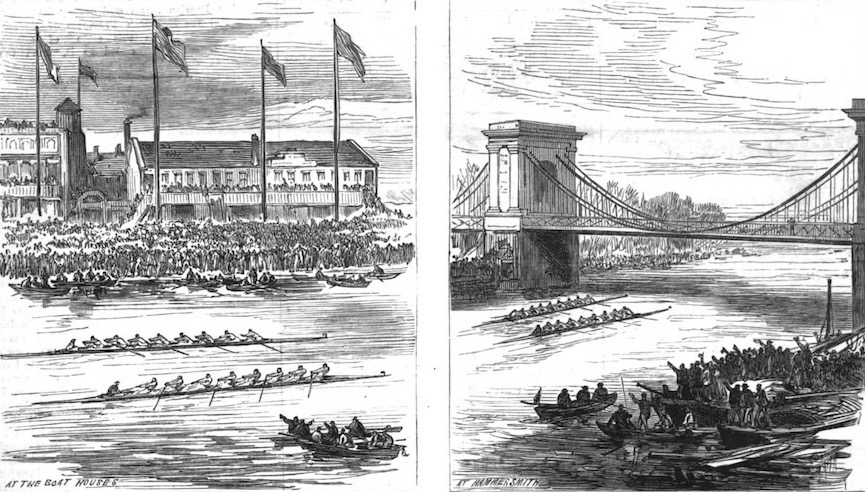

Left: Front cover of the The Illustrated London News for 27 March 1877. Right: Views of the River, The Illustrated London News, March 23 1872, p. 296.

History

The two crews of 1867, shown in The Illustrated London News of 20 April 1867, p. 397. Left: The Oxford crew. Right: The Cambridge crew.

The account accompanying these engravings in The Illustrated London News is helpful but not entirely accurate: the first direct contest was indeed in 1829, as stated below, but the next was not until 1836 (see Treherne and Goldie 12). This was followed by several races from Westminster to Putney in the later 1830s. But the boat race as we know it today, over the present Putney course, began only in 1845, the race of 1867 being the eighteenth one here (see Treherne and Goldie 43). Counting the earlier Westminster-Putney ones would make it the 24th rather than the the 22nd, a figure with which a current account agrees ("Where Thames Smooth Waters Glide"). However, in other ways, the The Illustrated London News gives a flavour of the times:

The Universities first met, at Henley-on-Thames, in 1829, and Oxford won. Since then twenty-two races have been rowed between them [see above]; and, although in 1860 Cambridge was three ahead, the fates have been against ever since; and, strange to eay, Oxford has always won the toss. Some croakers predicted that Cambridge would rest on its oars until another generation, of stronger thews and a less flashy stroke, arose to do battle, but, more especially after their very honourable defeat of last year, this was not to be thought of. [20 April 1867, 397]

Preparations

The Oxford and Cambridge Boat-Race: Practising on the Isis during the Floods, depicted in the Illustrated London News (3 February 1872, p. 113).

There was always a tremendous buid-up to the annual event. As proof of their manliness, dedication and determination, the Oxford team are seen here, out on the river in the most inclement weather, in training for the great day.

Expectations, Disappointments — and a Dead-Heat

The Oxford and Cambridge Boat-Race, in the Illustrated London News of 1872: Left: The crowd expected on Hammersmith Bridge (just half of a double-page spread on 23 March, p. 289). Right: The great day itself, when the atmosphere was in sharp contrast (30 March 1872, p. 309).

After the usual tremendous build-up, in 1872 there was a considerable let-down. On this occasion, Cambridge won easily, for the third year in a row. But there was little enough of either excitement or spectacle. According to the Illustrated London News, crowds failed to materialise on the handy vantage point of Hammersmith Bridge, and the whole event was dismal, partly because of the appalling weather, but also because of a certain failure of spirit all round. The sketch on the right above brings out the problems: a gentleman on the left, in the mid-ground, records people huddling under trees, umbrellas, in their cabs and so on, and on the right are poor people who would normally have entertained the spectators or plied them with hot potatoes or perhap chestnuts. A policement stands at the back, near the top, no doubt keeping an eye out for scoundrels. The race itself hardly features!

All this is confirmed by the periodical's account:

It is impossible to imagine a more hopelessly wretched day than Saturday last, and perhaps the weather was at its very worst just as the University boat-race was taking place. Fog, sleet, snow, and hail all struggled their hardest for the mastery; it is not, therefore, surprising that there was scarcely one third of the usual number of spectators. All the regular hangers-on to a boat-race — the venders of colours, eatables, and drinkables, “three-sticks-a-penny” men &c. — fared badly indeed; and we saw one large stand, constructed to hold at least two hundred people, with only three occupants. People had not even the excitement of anticipating a close race. Fortune had steadily set her face against the Dark Blues throughout. They had an inferior boat, a comparatively fresh stroke, within the last three or four days they were compelled to put a new man at No. 2, and, to finish their catalogue of misfortunes, they lost the toss, which on this occasion, owing to the bad mooring of the stake-boats, gave the winners an advantage of nearly half a length. At starting Cambridge was rowing thirty-seven to the minute, against Oxford's thirty-six, and maintained the lead for the first quarter of a mile, Then, however, Houblon quickened to forty, and drew nearly level for a few strokes; but at the Crab Tree half a length again separated the boats. At the Soapworks Houblon, rowing forty-one, again decreased the gap; but still the Light Blues maintained their even, regular thirty-seven, and shot the centre arch of Hammersmith Bridge (time, 8 min. 30 sec.) with an advantage of nearly a length. One more desperate effort of forty-two to the minute brought Oxfordnearly level at Chiswick Ait; but it was the last struggle. Houblon was beaten, Lesley and Nicholson were all to pieces, and though the other five, particularly Knollys, the substitute, worked like giants, Cambridge had only to paddle in front for the rest of the journey and win by two lengths (which might have been twelve at Goldie’s pleasure), in 21min. 16sec. The steering in the Cambridge boat was bad, and would have lost the race had the crews been evenly matched; but in all other respects the Dark Blues were terribly inferior to their rivals. [393]

Scenes on the cover of the issue of 31 March 1877 tell a completely different story, of a thrilling neck-and-neck contest: "The University Boat-Race Dead Heat."

On the other hand, the Boat-Race of 1877 provoked a positive frenzy. The account was entitled "National Sports: The Oxford and Cambridge Contests," and tells how the two teams fought it out from the start:

There was nothing between them at Craven Point; but at Rosebank the dark blues were slightly in advance. This advantage was only maintained as far as the Crab-Tree, where the Cambridge coxswain kept much the better course, and in making the shoot for the Soap Works drew out with a lead of about half a length. This advantage, however, was but momentary, as a spurt from Marriott rapidly closed up the gap, and as the two boats passed under Hammersmith Bridge Oxford, if anything, had the advantage. The curves in the river were now all in favour of the light blues, who began to creep away. They were perhaps half a length in advance at the foot of Chiswick Eyot, from which point the Oxford men began to row much beiter together, and gradually gained, in spite of Shafto quickening up to 37, and shortly afterwards to 38. At Chiswick Church the Oxonians were fully half a length to the good, and were rowing in better form than was shown by their opponents. Passing under Barnes Bridge, the leaders had increased their advantage to more than a length; and, as they were gaining slowly but surely, the race was apparently over, when bow caught a crab and broke his oar, which was only held together by the leather. Of course, after this he could only sit and swing, and, in spite of the desperate exertions of the other seven men, the Cambridge boat rapidly gained; and, though the genera) opinion was that Oxford won by about a couple of yards, the decision given by John Phelps was a dead-heat, a result with few parallels in the history of rowing. Thus appropriately ended one of the most sensational of the Inter-University boat-races. [295]

This of course was a terrible upset for the gambling community: "the result, by which all bets are off, will be chiefly regretted by the book-makers, most of whom must have stood to win considerable sums by the victory of either" (295). It is the only time in the history of the race that such a result has been recorded.

Teams were named in advance, and, by the time of the contest, the participants would have been so well known that no reminders were necessary. They were the heroes of what was or should have been (weather permitting) one of the great sporting events of the year. Naturally the race attracted some comments from the comic journals: Fun seemed to find plenty of material for this (see linked material below). But in a way this only reflected the extent of the nation's interest. Another indication of this can also be seen below: even the boats themselves were a public attraction, and here they are in 1869, placed side by side for visitors to admire at the Crystal Palace in Sydenham:

Exhibition of the Oxford and Cambridge Boats at the Crystal Palace (Illustrated London News, 27 March 1869, p. 308).

Links to Related Material

- The University Boat-Race from Two Points of View — “Training for the race” (top) and “Racing for the train” (cartoons)

- Boat-Race Idiots. — A Prophecy (cartoon)

- Boatraceana

- The Public Schools' Cult of Sport in Victorian Times

Bibliography

"Exhibition of the Oxford and Cambridge Boats at the Crystal Palace." The Illustrated London News. Vol. 54 (January-June 1869): 308.

"National Sports: The Oxford and Cambridge Contests." The Illustrated London News . Vol. 70 (31 March 1877): 295. Internet Archive, digitised from microfilm. Web. 1 October 2023.

“The Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race.” Illustrated London News. Vol. 60 (Jan.-June 1872). 3 February: 113. Hathi Trust. Web. 1 October 2023.

"The Oxford and Cambridge University Boat-Race." The Illustrated London News. Vol. 50 (January-June 1867). 20 April 1967: 397 Hathi Trust, from a copy in the Universty of Michigan. Web. 1 October 2023.

Treherne, Geo. G.T., and J. H. G. Goldie, Record of the University Boat Race, 1829-1883. 1883. London: Bickers & So, 1884. Google Books. Free to read.

"Where Thames Smooth Waters Glide." Thames.me.uk. 2 October 2023. https://thames.me.uk/index.htm

Created 3 October 2023