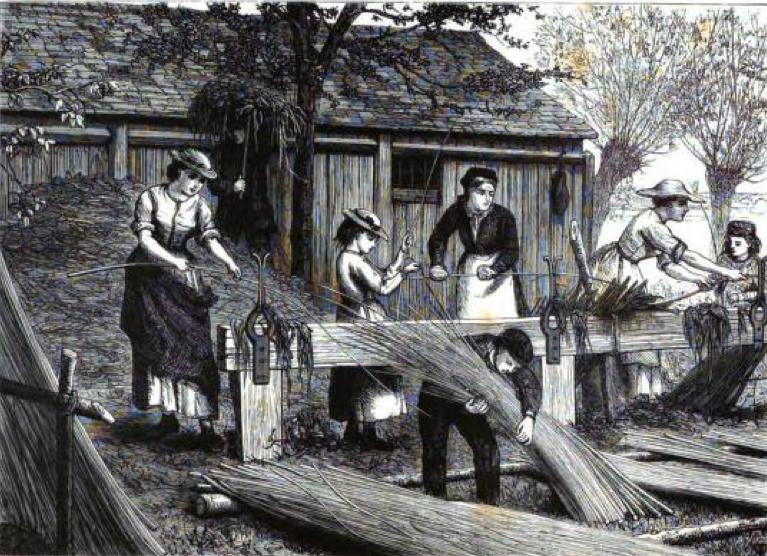

Osier Peeling by H. R. Robertson. Source: Life on the Upper Thames. Text and formatting by George P. Landow, [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the University of Toronto and the Internet Archive and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one.]

" . . . . twigges sallow, red

And green eke, and some were white

Such as men to the cages twight." — Chaucer's House of Fame.

THOSE rods that are intended for making white baskets require to have the bark taken off in the following manner. After being sorted, they are placed upright in wide and shallow trenches, called pits, with their butt-ends in water, which should be at least six inches deep. In some parts of the country a rivulet with a gravelly bottom is frequently chosen for the purpose. In this position they are made secure by posts and rails, so as not to be disturbed by the wind. In the spring, when the sap rises, they begin to bud and blossom as if they had been planted in the ground. By the end of April or beginning of May they will be found throwing out leaves and starting fresh roots. The sap is then sufficiently raised to admit of the removal of the bark from the rod, by drawing it through an instrument called a breaks which, by pressure, causes the bark to burst and to separate from the rod. On the banks of the Thames the break is now always made of wrought iron, and is used by the person standing in the manner shown in our drawing. In Mr. Miller's account of the process he describes the breaker as seated with a wooden break between his knees, a method still occasionally employed on the Trent and other rivers. Mr. Scaling has informed me that he has his iron breaks faced with india-rubber, and that they are thus rendered much more effectual, the tenderest willows being secured from injury.

In cold, unseasonable weather there is some difficulty in performing this operation properly, for the cold checks the flow of sap, so that by no effort can the bark be separated entirely. A thin under-layer remains attached to the rod, and this causes a brown, discoloured appearance, which very much reduces it in value. In order to avoid this, the process of couching is sometimes resorted to: the rods are laid down in a sheltered spot, well watered, and a large quantity of straw or farmyard refuse is laid over them, so as to exclude the external air. In about a fortnight they will "spire" all over, somewhat like barley in malting, and then the bark will separate freely. They must, after this, be placed against rails erected for the purpose, and carefully dried, and then stacked away under cover of some building impervious to wet. If damp when stored, or if any water reach them afterwards, they will become damaged in the same way as those not barked.

The first thing that strikes a visitor, on approaching the scene of the rodstripping, is a hum of merry voices mingled with the ever-recurring musical "ping" of the break: the shape of the instrument is not unlike that of a very narrow jews'-harp, and folly accounts for its resonance. The strong aromatic smell of the fresh peelings is probably what will be next noticed, as the air is quite laden with what is an agreeable, if slightly pungent, odour. The recently peeled rods, thousands of which stand everywhere about, look very attractive in their pure whiteness, fit, indeed, for a child's cradle — the actual destiny that awaits not a few of them.

The peelings from the rods make a valuable manure, especially for potatoe grounds; they supply also an excellent thatch, used in constructing sheds for cows or horses, which being generally too bitter for their taste is seldom touched by them.

It may be as well to explain what is meant by the expression "peeling buff," that we used towards the end of the last chapter. It is a process of removing the bark by means of boiling water or steam, instead of peeling by the ordinary method, and a stain of a buff colour is thus imparted to the rods. The colouring-matter producing this result is contained in the bark. It is said that baskets made of the boiled willow are firmer and wear longer than those of white rods, and that white baskets will be superseded when the superior merits of the others are understood. However, in a matter of this kind the goddess Fashion is arbitrary, and we think this change is no more likely to happen than that brown bread should take the place of white in the household because the former is proved to be the more nutritious. The system by which an account is kept of the number of bolts peeled by each woman is the ancient one of the tally. The word has survived in several cases: as a milk tally or score, a tally-shop or imlicensed pawnbroker's. We have never heard of the thing itself being still employed in any other business than the rod-stripping. It consists of a stick split as shown in the diagram — the larger part being kept by the foreman, and the smaller by the person working. When a bolt (that is, a bundle measuring forty inches round) is finished, the two pieces are laid together in their original position and a notch cut by the foreman simultaneously in both. The name of the individual to whom the account refers is written on the opposite side of the tally to that which we have represented, a slice being taken off the stick, as boys mark the ownership of their lead pencils. It is obviously of no use for any one to add a notch to her part of the stick, as of course it would not afterwards "tally" with the foreman's. [23-25]

[American Technology will destroy this occupation]

That the whole operation of osier-peeling, as we have described and illustrated it, may speedily be abolished, seems more than likely. A letter that we received from Mr. Scaling last year gives us news of an American invention which apparently will bring about the change we speak of. The machine is that of a Mr. Witte; it can be worked by horse or steam power, and is capable, at a very slight expense, of peeling a ton of rods per day. The cheapness of this method, and the ever-increasing difficulty of getting hands at any agricultural work, will, we fear, cause these anticipations to be realised. [27]

Bibliography

Robertson, H. R. Life on the Upper Thames. London: Virtue, Spalding, & Co., 1875.Internet Archive digitized from a copy in the University of Toronto Library.

Last modified 7 May 2012