ong loops of drenching rain drift on the wind across the wet valleys and wild fells. Few birds cry. Underfoot it's soft with trapped water: millions of gallons soaked up, up there, sodden, oozing, squelching at the touch of a foot. The Carlisle-Settle line crosses this hard country at its easiest point, yet it was still the wildest job ever undertaken by bare-handed navvies and the last big job they undertook unhelped by massive steam machinery. The working problems were scale, the weather, geography, bad-luck geology, and the sheer number of ups followed by steep downs in the hills. Navvies called it the Long Drag.

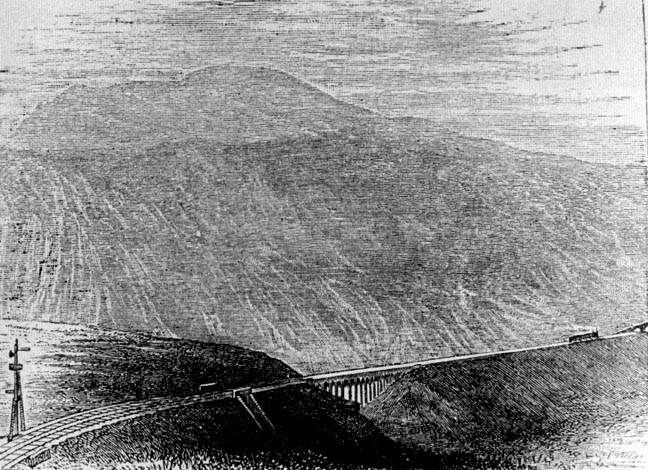

Blea Moor and the Lone Drag, 1870s. Click on thumbnail for larger image.

From Settle the line runs up Ribblesdale, under Ingleborough, Whernside and Pen y Gent. It pierces Blea Moor and rounds Dentdale like the 366-metre contour, then crosses the divide at the top of Wensleydale and drops from the wild and desolate to the soft and farmed, down into the Vale of Eden, where the viaducts have Gothic arches and all is rich and fat, to Carlisle.

Bad geology begins just north of Settle, a small stone-built town under its own crags. In Settle itself was a covered ambulance and, more ominously, a bog-cart with a barrel instead of wheels: horses often sank to their bellies in the soft ground, wheeled carts to their axles. Mud once ripped a hoof off a horse. Geologically the clay is a marine deposit, once soft but hardened by its own weight, striated by ice and strewn with glacier-carried boulders. Like dehydrated food it turns sloppy when mixed with water, and here the yearly rainfall can be measured in yards.

At the mountain-end of Ribblesdale, Batty Wife Hole was the capital of No 1 Contract, roaring like a gold camp in a colonial gold rush, brimming with traders and sauntering navvies in billy-cock hats, potters' carts, drapers' carts, milk carts, greengrocers' carts, butchers' and bakers' carts, brewers' drays, and hired traps. There were hawkers, pedlars, vendors of all kinds. There were stables and [115/116] stores and a hospital (used in the 1871 smallpox epidemic) with a covered walkway for convalescents. There was a post office, public library, the Manchester and Bradford City Missions and the mission school.

'Dispiriting, shiftless, unhomely, ramshackle, makeshift,' was what a Daily News man called it. Pigs snouted in the garbage and wallowed in the overflowing gutters. It was a disarrangement of wooden huts, coated with tarred felt, let to married navvies who took in lodgers at thirteen shillings a week for bed, board, and washing. The Welcome Home, one of the two pubs, was a hovel of two bare, cave-like taprooms with a separate building at the back where the landlady shut herself away in times of trouble to let the navvies fight themselves quiet.

But in spite of all that, the place boomed as the entrepot depot for the wilder parts of the line in the mountains. The victualling contract was held by a Batty Wife man who sent his carts daily into the hills. His beef came from Settle on the hoof and was slaughtered, bellowing, on Batty Green. He also ran a tommy truck on the works' railway, crammed to the eaves with halves of bullocks. Hereabouts navvies ate beef. Mutton was second best, bacon, a filler. Men ate eighteen pounds of beef a week.

Batty Wife Hole also had its own posh suburb, Inkerman, blending into it like a little navvy conurbation. Gentility resided in Inkerman: the surveyor, the contractor's staff, the clergymen, Dr Leveson who was born in Jamaica, schoolmistress Januarye Herbert who lodged with Mr Tiplady of the Bradford City Mission, and the colony's police — Archie Cameron and Joseph Goodison, tolerated but despised. The rest of the colony was given over to wild, roistering, rag-tag navvies.

It began when Joe Pollen came up from the Surrey-Sussex Junction in 1869 in a wooden caravan like a peak-roofed cabin on wheels. Snow lay all winter on the hills and in the fleeces of the hill sheep. All winter the little wooden van was filled with Pollen, his wife and two daughters, and ten men from the survey team. Next Spring, when work began in earnest, Joe built himself a tommy shop and started a daily bus service to Ingleton. He was also the undertaker, carrying the dead down to the burying-ground in the trees by the dry bed of the Doe in Chapel-le-Dale.

'What with accidents, low fevers, smallpox, and so on,' he said two years after he came, 'I've toted over a hundred of us down the hill. T'other day I had toted one poor fellow down — he were hale [116/117] and hearty on Thursday, and on Tuesday he were dead o' erinsipalis: and I says to the clerk as how I thought I had toted well nigh on a hundred down over the beck to Chapel-le-Dale. He goes and has a look at his books, and comes out, and says, says he: "Joe, you've fetched to t'kirkyard exactly a hundred and ten corpse." I knowed I warn't far out.'

One day, late in 1872, the Pollens threw a party for Betsey Smith, a friend from the Surrey-Sussex Junction. It was nearly winter, early in the evening as the shifts changed. Weak, wet light fell on the mud of the camp. Betsey Smith and the Pollen girls sat by the coal-fire in the keeping room, while a lodger cut Joe's hair in the dormitory. Mrs Pollen, a big and burly woman, handed round rashers of bacon and buttered toast until Mr Pollen came back to reminisce about Batty Wife's beginnings. From the lodgers' room came the muted squeak and scrape of a violin and then a black-eyed young navvy tapped on the dormitory door and came in, blushing. Could they join the company, if they behaved properly and brought a fiddle and a bucket of beer? The company, tired of being polite to each other, said yes, and the lodgers clumped in with a bucket of ale and a whisky bottle. The black-eyed navvy danced and fiddled, double-shuffling and stamping, a kind of clog dance in navvy boots.

After a time Mrs Pollen was called into the tommy shop attached to the hut. While she was gone a strange navvy, calling himself Wellingborough Pincer, knocked at the outside door of the living quarters. Joe, a Wellingborough man himself, welcomed him — until he made for the beer bucket and began emptying it down his throat. Mrs Pollen came back, saw at once what was happening and threw Pincer out: literally and physically, bunching the back of his jacket into a fistful of cloth.

Pincer huddled outside in the chill making himself pitiful, begging to be forgiven. Mrs Pollen relented and let him in. Pincer, unreformed and unrepentant, made straight for the ale can and hit Tom Purgin in the eye. Mrs Pollen, now hard and merciless, dragged him, heels bumping, across the bare floor-boards and dropped him in the mud outside. Pincer banged on the shutters, demanding access to the ale can. Joe, local loyalties all forgotten, then unleashed his bulldog - a massively jawed, strappingly chested, red-eyed brute (also called Joe) — and opened the outside door. In the darkness they heard Joe (the dog) gargling and snarling, then a mud-softened thump. [117/118] Pincer sued the Pollens for unlicensed drink selling and setting a dog on him, but the Ingleton magistrate found against him and made him pay the court costs. Pincer disappeared soon after. Gone on tramp, said some: at the bottom a sump-hole in the Blea Moor tunnel, implied others.

The Hole of Batty Wife Hole is supposed to be the source of the Ribble, though it looks more like a sump than a well, swallowing water as it does down its churns. It's an oval in the mud, about twenty feet deep, where Mr Batty dropped his wife's murdered corpse. To the east is a low line of out-cropping rock like a row of rotten teeth. Both are to one side of a vast open bowl filled with little but space, rain, mist, moving air and the Batty Moss viaduct. A million and a half bricks went into the viaduct in spite of a wind that could blow men off the scaffolding.

Several settlements serviced Nos 1 and 2 Contracts: Batty Wife Hole/Inkerman, Sebastopol/Belgravia, Jericho, The Barracks, and Salt Lake City, an isolated encampment on the shoulder of Blea Moor, north west of Batty Wife Hole. Sebastopol and its posh suburb Belgravia were set square in the swamp beyond the vidaduct. On his way there the Daily News man met an old navvy with a whitlowed finger who had been to the doctor's in Inkerman. Together they dropped into a friend's hut in Sebastopol. Outside was squashy bog, inside, a blazing fire. The landlady drew a quart of ale and put the money for it straight into a child's money box.

The gossip was of the up-tunnel goings-on. Black Sam had had his head cut open in a mass brawl to settle the Anglo-Irish question at The Barracks. Johnson's wife got drunk at her own wedding and chucked her bridegroom bodily out of the hut. Then she fell flat in the mud and not even her fancy man would pick her up.

Even a little rain did a lot of harm in that awkward geology and the Daily News man walked mid-leg in mud the mile and a bit to the Blea Moor tunnel. A shower of rain, even the jolting of a wagon, turned dry clay into slurry. It settled glue-like on the wagon bed and instead of slipping cleanly out often dragged the wagon over the tiphead. Bulling irons were needed all the time.' [Bulling irons are U-shaped iron bars, one end of which fitted between the spokes of a wheel, the other under the flange of the rail, thus locking the wagon securely to the track, stopping it toppling over.]

'I have known men,' said the chief engineer, 'blast the boulder [118/119] clay like rock, and within a few hours have to ladle out the same stuff from the same spot like soup in buckets. Or a man strikes a blow with his pick at what he thinks is clay, but there is a great boulder underneath almost as hard as iron, and the man's wrists, arms, and body are so shaken by the shock, that, disgusted, he flings down his tools, asks for his money, and is off.'

Blea (dialect for bleak) Moor is an immensity of barren fell, smooth save for a few beck scratches, and not many of them, though the Little Dale Beck and the Force Gill Beck were nuisances which had to be aqueducted over the railway. (They still are.) Down the mountain, the streams flow together as the Winterscale Beck until it sinks into a swallow-hole near Chapel-le-Dale and wells up again as the River Doe.

The heaviest work and the heaviest men were on the moor near the tunnel, among them the best two gangs in all England, each twenty-five strong. All were English, all were piecemen, they had no gangers, and all they needed was an engineer to check their levels and measure their work once a fortnight. All lived in Jericho — two lines of huts, grubbed about by pigs, with a solitary pub in a rock-roofed, semi-subterranean hole.

The Daily News man, along with an engineer, the contractor, and the Manchester City missionary were looked after in Jericho by three full-bodied navvy women. One nursed a child. In the oven was a massive piece of beef. On the fire, a potato pot. The landlady offered whisky, but gave them beer when they asked for it. The engineer said things were looking up in Jericho: there hadn't been a fight for a fortnight, whereas one Sunday in summer he'd counted seven brawls going on all at the same time. A navvy, off work with a bruised foot, said it was the cold weather, but the engineer was certain Jericho was getting respectable.

From Jericho you look across to the bulk of the mountain called Ingleborough. Whernside is hidden by its own huge shoulder. It's spongy, squelchy, sopping country, where the wind snatches the breath from your mouth. Behind, on the Moor, you can still see the spoil heaps from the tunnel and the brick ventilation shafts.

Unrelieved hardness was the trouble in the Blea Moor tunnel. 'Not a spoonful,' said the Daily News man, 'comes out without powder.' Most of the rock is limestone, gritstone, or shale, and the idea was to follow the shale as closely as you could. Charge holes were hammered out with drills and about a pint (two tots, to the navvy) of gunpowder, packed around a canvas-covered fuse, was [119/120] used in each. Dynamite was better and safer but it cost two hundred pounds a ton just to carry it there, five times more than gunpowder. Without its detonator, dynamite burned safely like a wickless candle. Navvies carried it in their trouser pockets to keep it warm. It looked like potted lobster.

Jack rolls, like the windlasses over wishing wells, were the first winding engines at the tunnel, but later they used horse gins and, lastly, steam. The first steam engine was dragged up the mountain over a narrow gauge railway by a series of windlasses called crabs. The boiler came first, then the engine, then the whole thing was rivetted together on the mountain and used to haul up its sister engine.

Most of the miners were from Devon or Cornwall, with some Irish, the only place on Nos 1 and 2 Contracts where they were tolerated. They all lived in The Barracks, which was probably at the tunnel's northern end, overlooking Dentdale.

Eight feet of rain a year falls on these mountains. In July 1870, the cutting at the northern end of the tunnel was still just a hole isolated from the rest of the line. When a wave of rainwater hit it, it filled like a pond. Two men drowned and the rain trapped two others in the tunnel itself. They scrabbled on to a wagon and the men outside could see the taller of them with his face upturned to the roof of the tunnel trying to ward off the water with his hands, paddling it away from his mouth. Rescuers cut a hole to drain the rainwater. The taller man was still alive but the shorter man was dead, his mouth stopped with clay.

'He came from Kingscliffe in Northamptonshire, hard by my own native place,' said Joe Pollen, 'and I got a coffin for the poor chap, and toted him down to Ingleton, and sent him home by the railway.'

From The Barracks you can see the railway arcing around the mountain like the timberline. Above, all is bare and barren, below are broad-leaved trees and farms.

Dendry Mire is a badly drained little hollow on the heights between Wensleydale and Garsdale. At first there was to be an embankment there and for two years they dumped a quarter- million cubic yards of muck, which promptly sank. In places, walls of peat fifteen feet high were pushed up on either side of the vanishing, upside-down embankment. In the end they settled for a viaduct.

Hereabouts, too, a gullet once quietly closed itself like a quick [120/121] healing wound, engulfing the works railway after a minor fall of evening rain.

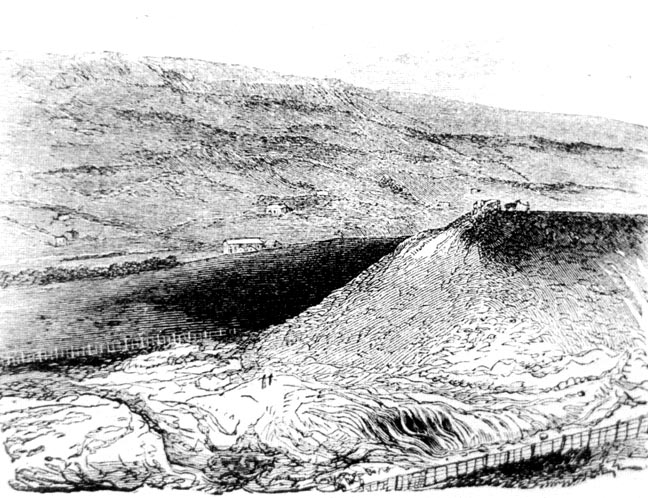

Intake Bank, Carlisle-Settle, 1870s.. Click on image to enlarger it.

Even the Intake embankment at the very top of the Vale of Eden took a year to make. The Eden is only a few yards long here, trickling off the great convoluted slopes of Abbotside, dropping as a waterfall into a pool in a gorge, before turning north past the Intake embankment. For a year they tipped without moving the tiphead a centimetre forward. The muck sludged slowly down over itself like cold unsolidifying lava, an unlovely heap of clay, glistening and wet.

The three northern contracts were in the easy country of the Vale of Eden, but even so the Crow Hill cutting was five and a half years in the making. Some weeks a ton of gunpowder was exploded to blow up the boulder clay and crack open the boulders embedded in it. It's still an unusually narrow gash of a cutting, lined with a welt of conifers.

The irony was that the men who worked the hard country in the south were softer in their behaviour than the men in the easy country to the north. Sports soaked up what energy was left after work in the wild country of Nos i and 2 Contracts: cross-fell races over Blea Moor; bare-knuckle fights to pick the Cock of the Camp. In the easy country they rioted — at Armathwaite in the Vale of Eden where cottage smoke idled through the trees in the hollow by the river, the very image of Victorian peacefulness. Armathwaite is still unblemished, an open airy place in a hilly, hedged and wooded country where the Eden flows quick and shallow. Old cottages squat around a cobbled courtyard. Trees hide the castle by the river.

In the 1870s the village had at least four pubs. Two have closed. The New Inn, across the Eden, has gone completely — buildings and all.

Trouble incubated slowly, rather than broke out, one Saturday evening in Octoberober, 1870, when an Irish gang robbed a Scotsman outside the Armathwaite tommy shop. At the same time, English and Irish gamblers quarrelled in the New Inn. The Irish stoned the place. Inside the New Inn a half-drunk Irishman called Cornelius Cox sat by the fire in the front kitchen with William Kaisley, Punch Parker and Portsmouth Joe White. Portsmouth suddenly hit Cox with his clubbed fist and dragged him into the backyard where, in light spilling from the open door, Punch hit him on the head with a dyking spade. Kaisley came out and kicked Cox in the face. [121/122] Margaret Graham, servant, mopped up blood in the front kitchen. 'There was very little of it,' she said. 'I don't think above a pint.' The Englishmen tossed Cox's body over the garden wall into a field where PC Whitfield found him at midnight. Cox had vomited and his hair was glued to his skull with coagulated blood. Whitfield sent him home in a wheelbarrow to die.

Senior police officers from Penrith arrested Punch, Portsmouth and Kaisley on Sunday night. Then, early on Monday morning, Inspector Bertram heard that mobs of English navvies were massing to drive the Irish off the line. At Jamieson's cutting, about half a mile from Armathwaite, he found an Irish gang working peacefully, but on his way back he ran into a mob of English navvies armed with sticks and coppey stools, coming from the deep rock cutting at Low House. He stopped them by holding up his hand like a man on points duty and, to be on the safe side, ordered his own men to draw their cutlasses. The navvies brandished sticks. Bertram and his men rushed them (he told the court), drove them back, and disarmed them.

Back in Armathwaite he heard another crowd was coming from the Baron Wood cutting and tunnel, partly out of sight of the village to the south, cut off by a bend in the Eden and by low crags. The mob marched like soldiers in columns of four. Bertram stopped them in the wooded lane outside the village. They had leaders: Joseph French (29), from Warwickshire; Joseph Draper (28), from Leicestershire and Thomas Jones (29), from Cheshire. Draper took a whip from his smock and cracked it.

'Why the hell are you stopping us here for?' Jones wanted to know. 'You must read the Riot Act.'

'Drive through the bastards,' said French.

Bertram couldn't control them and they broke through to join the disarmed men in Armathwaite. Farmers were too scared to lend him a horse to send for reinforcements, so he went to see if he could borrow a mount from Mr Bell, the works manager, in his office near the New Inn. Through the window they saw the English mob crossing the Eden from Armathwaite — Where it all happened is confused. The railway itself is on the hillside above the village. According to local remembrance, the New Inn was below it, across the Eden. Perhaps the 'works' next to the pub were offices and stores and the men's huts were up the hill closer to the railway. Bell ordered the gates to be shut. [122/123]

'Is it going to be an Irish or an English job?' the men shouted, storming the gates, calling for the master. The walking ganger opened the gate for the leaders, who went in to speak to Bell, briefly, before coming out again to tell their mates the company had conceded. The Irish had to go. They led their mob to the Irish huts, kicking down doors and menacing the people inside.

'I never saw such a sight in my life,' said Bertram. 'The Irishmen were frightened, and their wives and children were shouting and crying in great alarm. At that time the two hundred men were flourishing their sticks, and daring the Irish to come out.'

'The buggers aren't coming,' Jones shouted. 'We'll have to go and bring them out by force.'

But it took only half an hour to clear the camp as the Irish made off into the hills and woods smashing what they couldn't carry. By two o'clock only three Irishmen were left: the dead man and his two keepers.

French, Draper, and Jones got twelve months hard labour apiece.

Then at two o'clock in the morning on the last Sunday that Octoberober, when autumn was already in the woods along the Eden, a navvy broke the leg of Touchy Harrison, gamekeeper on the Edenhall estate. Earlier Touchy had noticed snares in Baron Wood on the high ground above the looping river and like a fool lay in wait, sitting in the fresh-smelling darkness until the two poachers came back. One, a tunnel tiger called Dale, broke his leg. Dale got two years hard and lost his hare.

It all dimmed a little of the glory of Nos 1 and 2 Contracts, though probably it was no more than the Victorians expected of their navvies: stallion-like strength clothed in flannel and moleskin, and pointless violence. Navvies were always feared for the brutality of their riots. [123/124]

Last modified 21 April 2006