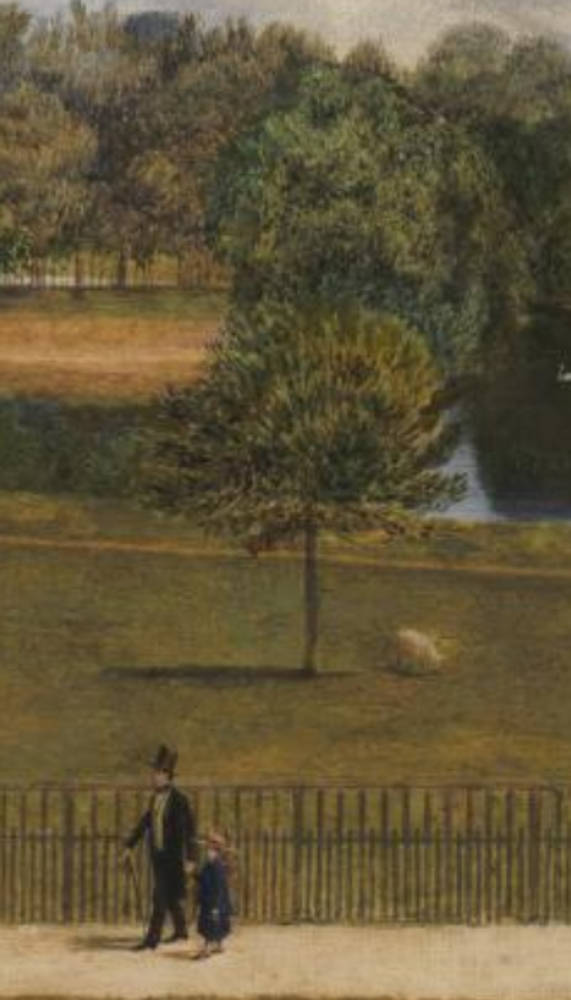

May, in the Regent's Park, by Charles Allston Collins (1828-1873). 1851. Oil on mahogany panel. 17 1/2 x 27 1/4 inches (44.5 x 69.2 cm). Collection of Tate Britain, accession no. T03025. Purchased 1980. Image kindly released by the gallery under the terms of the Creative Commons Licence CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported). [Click on all the images to enlarge them.]

Collins exhibited this painting at the Royal Academy in 1852, no. 55. It is the only landscape of this type Collins is known to have executed and one of the first Pre-Raphaelite landscapes ever to be exhibited. As Carl-Johan Olsson so correctly observed: "Although the picture was painted indoors, it was executed entirely with the landscape in view and can, in that sense, be regarded as closely related to the early form of plein-air painting that emerged in Pre-Raphaelite art around 1850" (189). The title of this work could either refer to the month Collins began the painting or to the "double pink" Hawthorn bush, also known as May [Crataegus laevigata], in blossom in the left foreground of the composition.

In August 1850 the Collins family had moved from Blandford Square to 17 Hanover Terrace which faced east-northeast across Regent's Park. May, in the Regent's Park is thought to have been painted from a window at this address, looking eastwards across the park. Jason Rosenfeld has remarked: "It is the only pure Pre-Raphaelite landscape of a central London subject, and is remarkable in its fidelity to nature, expression of Pre-Raphaelite principles, and documentation of the particularities of this metropolitan park without any evident religious or social themes" (94). Rosenwald then goes on call this "an escapist vision of a privileged view," and to explain:

This extremely straightforward view out of a window onto both private and public urban greenery is actually complex. Collins conflated the prospect from his upper-floor bedroom to the distant park across the Outer Circle – where a man and young girl head north towards the upper reaches of the park and Portland Town – with that of the first-floor, more head-on perspective of the garden frontage. The foreground of the picture, with its hawthorn tree and other planting, lies in the private grounds of Hanover Terrace. Beyond the Circle and the iron fence are the park's lawn with sheep serving as mowers, the boating lake with a solitary swan plying its placid waters, and a variety of deciduous trees. In the middle left distance, within the park, are the gothic peaks of St Katherine's Lodge, destroyed in World War II, but then part of a hospital complex of the same name. At the far right looms the barely perceptible bulk of Chester Terrace…. It is a singularly Pre-Raphaelite painting that, brightly chromatic, works against the tradition of picturesque views of gardens out of windows. It lacks framing devices around the view, such as elements of the window, tall foreground motifs at the sides that define space, or plunging lines that draw the eye back into depth. [94]

Details. Left: Pond and trees at left. Right: Man, child, and trees at right

Rosenfeld felt this work prefigured later landscapes by Ford Madox Brown, such as his An English Autumn Afternoon, Hampstead of 1852-56 or Hampstead from my Window of 1857. Olsson felt the light in Collins's painting was reminiscent of Madox Brown's The Pretty Baa-Lambs dating from about this same time period (189).

Alison Smith has discussed the features of this landscape painting which made it appear distinctly "unnatural" to contemporary viewers:

Although a prospect over a parkland was by no means unusual, the painting is innovative in its disregard for traditional landscape formulae. The 1852 Royal Academy exhibition also included William Mulready's Blackheath Park, which, despite criticism of Pre-Raffaellesque eccentricity, was more conservative in approach being softer in execution and incorporating rustics who blend in with the landscape. By contrast, the two strolling figures in Collins's composition appear conspicuous in their dark, elegant, urban dress, as if surveyed unaware through the lens of an optical instrument. Rejecting conventional meandering lines of recession, Collins confronts the scene straight on, accentuating right angles where uprights meet shadows. The brightly illuminated route of the Outer Circle abruptly bisects the composition, separating the private realm of the hedged suburban garden from the more orderly area of the public park, signified by the neat vertical palings that almost mimic the prim gait of the gentleman and his daughter. The clarity of focus sustained throughout the painting further serves to emphasize what is essentially an urban demarcation of space…With hindsight, however, we can see that such devices comprise an effective language for conveying the detached gaze associated with modern urban perception. [69]

When it was shown at the Royal Academy in 1852 a critic for The Art Journal considered this landscape eccentric despite the precision with which it was painted:

No. 55. May in the Regent's Park, C. Collins. Certainly among the most eccentric of the curiosities of landscape painting: a view across the enclosure in the park from one of the dining-room windows, at least one of the gardens facing the park. The principal of the composition is a large bush of pink "May,"" with parterre shrubs and flowers; then we have the line of park palings; then the park and trees; but we must say that all this is exquisitely painted, the May and foreground material are marvellously described, and all kinds of inexorable straight lines are boldly and importunately brought forward, despite the useless and absurd rules of composition, and the elaborate "finish," which is not redolent of nature. [166]

The reviewer for The Athenaeum lamented the extreme unrealistic Pre-Raphaelite detail shown in the picture and its apparent lack of conventional composition:

Some of the disciples of Mr. Millais already evince a tendency to exaggerate his mannerisms. Thus, Mr. Collins shows us May in the Regent's Park (55) from a window in Sussex Place; and so minute is the scale – the very "form and pressure" of the flowers, red, white and blue, and of the shrubs – that we could creep about and through them. The botanical predominates altogether over the artistical, – and to a vicious and mistaken extreme. In nature there is air as well as earth, – she masses and generalizes where these fac-simile makers split hairs and particularize. They take a branch, a flower, a blade of grass, place it close before them and as closely copy it, – forgetting that these objects, at the distance imagined in the picture, and reduced to its scale, could by no means be seen with such hortus siccus minuteness. [582]

The Illustrated London News did not like any of Collins's submissions to the Royal Academy in 1852: "As for Mr. Collins's May in the Regent's Park (55), the absurdity of the production is the more obvious from its being so misplaced – a tea-tray, not a picture-frame, was its appropriate vehicle" (407). The critic later went on to compare it to Ford Madox Brown's Jesus Washing Peter's Feet which he also disparaged: "This is an effort worthy of the nursery, as Mr. Collins's May – Regent's Park is of the pantry" (407).

W. M. Rossetti in The Spectator praised this as an excellent example of Pre-Raphaelite landscape art: "In landscape art, as well as in subjects, Pre-Raphaelitism is visibly making its way; exemplified here by the scrupulous literality of Mr. Collins's May in the Regent's Park, – an excellent little slice of nature – park nature – in its way" (593).

David Masson in The British Quarterly Review admired both its Pre-Raphaelite detail and its colour: "No. 55 is entitled, May in the Regent's Park, and is a curious and very pretty little specimen of minute painting of vegetation. The effect is as if one were looking at a piece of the park through an eyeglass from the window of one of the neighbouring houses. The Pre-Raphaelite qualities most conspicuous in it are those of simple fidelity to the objects represented, with minute finish of colour" (213-14).

Collins apparently sold the painting for £100 at the time of its Royal Academy exhibition to a Mr. Crooke of Cumberland Terrace on the other side of Regent's Park.

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

"The Exhibition of the Royal Academy, 1852." The Art Journal New Series IV (1 June 1852): 165-176.

"Fine Arts. Royal Academy." The Athenaeum No. 1282 (22 May 1852): 581-83.

Masson, David. "Pre-Raphaelitism in Art and Literature." The British Quarterly Review XVI (August 1852): 197-220.

May, in the Regent's Park. Tate. 15 September 2024.

Olsson, Carl-Johan. "May, in the Regent's Park." The Pre-Raphaelites. Ed. Mikael Ahlund Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, 2009, cat. 80. 189.

Rosenfeld, Jason. Pre-Raphaelites Victorian Avant-Garde. London: Tate Publishing, 2012, cat. 68. 94-95.

Rossetti, William Michael. "Fine Arts. The Royal Academy Exhibition." The Spectator XXV (19 June 1852): 592-593.

"The Royal Academy." The Illustrated London News XXII (May 22, 1852): 407-08.

Smith, Alison. Pre-Raphaelite Vision Truth to Nature. Eds. Alllen Staley and Christopher Newall London: Tate Publishing, 2004, cat. 28. 69.

Staley, Allen. The Pre-Raphaelite Landscape. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973. 83, 91, 150.

The Tate Gallery 1978-80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions. London: Tate Gallery Publications, 1981. 11-12.

Warner, Malcolm. The Pre-Raphaelites. London: Tate Gallery Publications/Penguin Books, 1984, Cat. 43. 101-02.

Created 14 September 2024