arie-Françoise Catherine Corbaux, generally known as Fanny, was a well-known artist of the pre-Victorian generation, in mid-life reinventing herself as a scholar of biblical literature. Her elder sister Louisa, although following a largely similar path in the practice of her art, achieved far less fame.

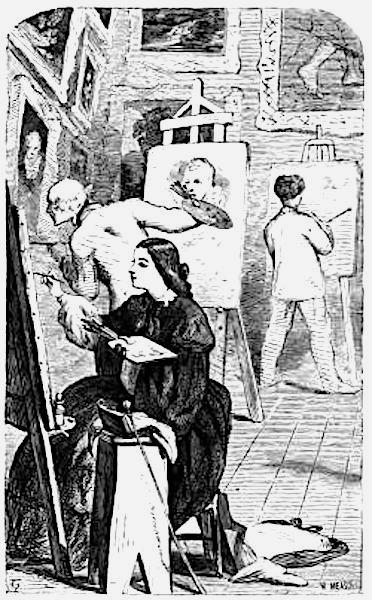

Fanny painting in the National Gallery"

(Johnson, facing p. 140).

The sisters’ English father, a well-known statistician and mathematician, was a francophile and they began their lives in France. As children they cultivated artistic talent, encouraged by their mother’s example, with Fanny winning a silver medal from the Society of Arts in 1827, its Isis medal in 1827 and 1828 and a gold medal in 1830, and Louisa a silver medal in 1828 and 1829. In the late 1820s Mr Corbaux suffered financial reverses and a consequent breakdown, obliging the two girls to turn their talents to the mundane end of earning a living. To this end, they settled in London (initially in Lambeth) and Fanny applied herself to copying at the National Gallery and British Institution in order to hone her abilities. As an account of her life in The Englishwoman's Reviewin 1857 put it, “She lost no time in profiting by the advantages they offered, and in a case like her own, the opportunity of seeing others paint was no less valuable than the acquisition of good models....[S]he made many copies and small studies, and learned a great deal of the resources and management of watercolours; so that, at the age of eighteen, she found herself able to launch fairly into professional life.” This action, along with her attempt to attend Royal Academy lectures, gave her the character of a pioneer for women’s rights in the British art-world in the eyes of later commentators.

Exhibiting first as a copyist at the British Institution in 1829, Fanny was accepted at the Royal Academy exhibition in that same year, and membership of the Society of British Artists (such as it was then for women: in fact, they were allocated the title of honorary member) in 1830 was followed by election to the New Watercolour Society in 1839. During the thirties her name became familiar not only in London exhibition but equally in the field of high-class engraving and lithography, exemplified in such publications as the Book of Beauty, The Keepsake, Heath’s Picturesque Annual and The Amulet. Equivalents for children, usually content be less refined and precious, included Maria Carter Hall’s Juvenile Forget-Me-Not (which included the sisters in 1833). The favourite subjects of this aesthetic were literary heroines – Shakespeare, Byron, Scott, Goldsmith, Hemans, Landon, being staple sources – and upper-class portraiture. Fanny’s work was in watercolour, often miniature, and while these originals could be exhibited at such venues as the British Institution and the New Watercolour Society, they were just as likely to become known to the public by their reproduction as prints or in books: hence, typically, her illustrations of characters in Byron’s poetry published in a bound volume as steel engravings by Charles Heath in 1846. Royal patronage from about 1831 (including portraits of the Duchess of Kent and her daughter Princess Alexandrina Victoria the eventual queen, published in the Lady's Magazine, May 1831), generated many commissions from aristocratic and upper-class families, such as the Harpur-Crewes at Calke Abbey, Derbyshire.

While portraiture was essentially an art of imitation (and for this reason was often at this time said to be suitable for women artists), there was some room for imagination in the decorative illustration and print-making by which both sisters made their living: thus Thomas Moore's Pearls of the East (1837), or Cousin Natalia's Tales (1841); although fidelity to the source was expected and lines from the written text often reproduced alongside the image, reinforcing its illustrative function. In this body of work a tendency towards a genteel Orientalism can be discerned, although whether this reflects the artist’s own taste or that which the print-buying public was assumed to have is impossible to know at this distance. Characteristic compositions such as The Secret Tryst (undated, Christie’s 2006), Primroses (undated, British Museum) and The Child’s Offering (1837, British Museum) were probably commissioned as illustrations of literary subject-matter, but accounts of Fanny’s life state that she would have produced original imaginative works had she sensed the patronage for it, so it can be suspected that later pictures such as The Convalescent (New Watercolour Society, 1850) indicate the artist attempting to move into original invention.

Fanny remained a favourite of print-publisher George Baxter’s, with Le Souvenir (1848) and The Day before Marriage (published 1854) standing as good examples of why her work was so popular with the early Victorian public and, at the same time, why it went out of favour in the more contested climate of the 1850s and 60s. The ‘Book of Beauty’ tradition which Corbaux’s work exemplifies, with its basis in literature, music and elegance, having been enjoyed for its perceived femininity, became seen as niminy-piminy once middle-class taste began to form, and became thus identified with all that was not modern.

There is some indication in her pictorial work that Fanny Corbaux was drawn to religious matters - Rachel (1848), Leah (1848), Hagar (1849), Hannah (1852), Miriam (1852) - but it was hardly to be expected that she would emerge as a student and interpreter of religious history: but the articles that appeared in the Athenaeum, collected together as The Rephaim and their connection with Egyptian History (1852), were well received. Her self-confidence in this new direction is attested to by her engagement with the scholarly establishment (e.g. the Syro-Egyptian Society, 1850 on) as well as by her next publication, The Exodus Papyri (1855). It was with regard to this aspect of her activities that in 1872 Fanny was awarded a civil list pension. She was in poor health for some years before her death in 1883 (in 1870 the sisters removed from Kensington to Brighton – a sure sign of the quest for a healthier climate), identifying herself as retired in in the 1871 census.

Louisa’s career followed a similar trajectory to Fanny’s, and on occasion they worked together (Fanny designing and Louisa lithographing), and it is not clear why she did not become as popular (there is hardly any work currently known by which her proficiency can be appraised). She appeared at the Royal Academy exhibitions 1833-5 and was elected to the New Watercolour Society in 1837 (preceding her younger sister). She too was commissioned for pictures published as engravings or lithographs, as well as lithographing others’ work, and also appeared in the more modern field of sheet music illustration, with two designs based on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s enormously popular novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (serialised 1851-2, published as one volume 1852) for the sheet music of “Topsy’s Polka” and “Eva and Topsy” (Spellman Collection of Victorian music covers, University of Reading); and one of the child-and-pet-animal compositions of which she made something of a speciality for “Pet of the Family Polka” (1853). This may have been an ongoing field of work, as another instance of it is documented as late as 1877. In 1852, Louisa published The Amateur’s Painting Guide; her latest documented work, in children’s book illustration, occurred in 1878 (Annette Salaman’s Aunt Annette’s Stories to Ada).

Bibliography

Anonymous, "Remarkable Women: Fanny Corbaux." The Englishwoman's Review, 8 August 1857: 12.

Clayton, Ellen C. English Female Artists. London: Tinsley Bros, 1876, 68-9.

Gray, Sarah. The Dictionary of British Women Artists. Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 2009, 78.

Johnson, Joseph. Clever Girls. London: Gall and Inglis, 1862, 140-151.

Yeldham, Charlotte. Women Artists in Nineteenth-Century France and England. New York: Garland, 1984.

Created 19 April 2023