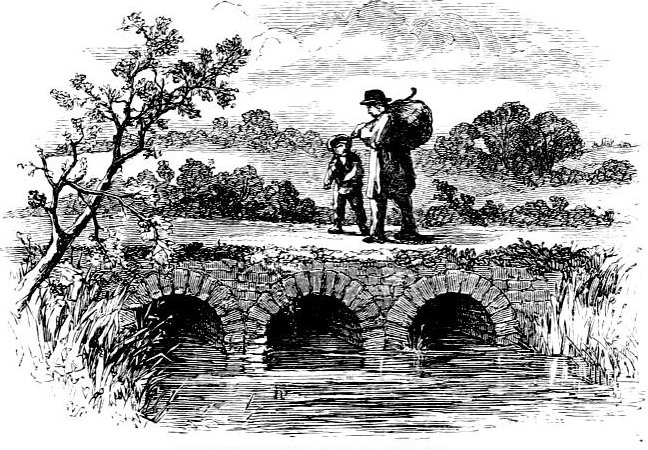

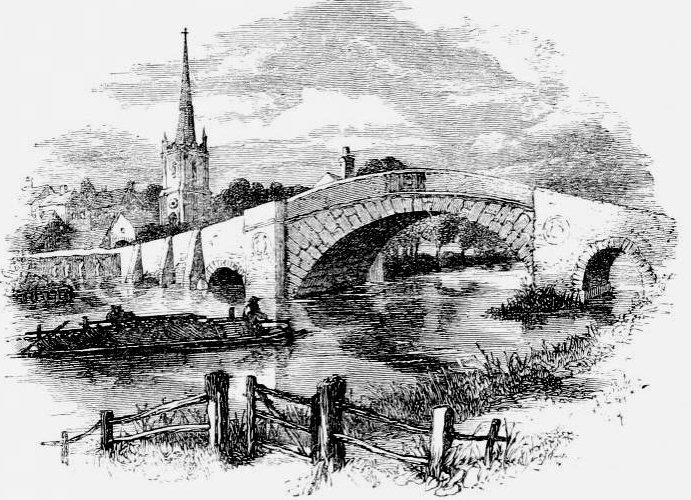

Left: The First Tunnel. Right: The First Bridge on the Thames. From the author's The Book of the Thames, whose many illustrations he credits to F. W. Fairholt, F.S.A. and W. S. Coleman. [Click on these images and those below to enlarge them. — George P. Landow.]

Standing beside the cradle of mighty Thames, and looking forth upon a landscape wealthy in the gifts of tranquillity and hope, and in the varied beauty of sunshine and shade, there rises the tower of the village-church — the Church of Cotes.. . . A walk along the first meadow brings us to the great Bath Road, under which there is a tunnel formed to give passage to the Thames when "the waters are out." In June it was dry, sheep were feeding at its entrance; but in winter it is too narrow for the rush of the stream that has then gathered in force. . . [12,13]

Close by this tunnel, and about half a mile from Thames Head, is the engine-house of the Thames and Severn Canal, which, by continual working to supply water to the canal, drains all the adjacent springs, and is no doubt the main cause of absorbing the spring -head of the river. This engine-house is an ungainly structure, which the lover of the picturesque may well wish away; but although a blot upon the landscape, it is happily hidden from the valley in which the Thames has its birth. The course of this canal we shall describe when we reach its terminus at Lechlade.

Half a mile further, perhaps, and the burns begin to gather into a common channel; little trickling rills, clear as crystal, rippling by hedge-sides, make their way among sedges, the water-plants appear, and the Thames assumes the aspect of a perennial stream: so it runs on its course, and brings us to the village of Kemble, which occupies a hillock about half a mile from the bank; its church -spire, forming a charming feature in the landscape, standing on a gentle acclivity, and rising above a bower of trees; — the railroad is previously encountered, the river flowing underneath. This church we shall visit before we resume our tour. . . [14]

Resuming our walk by the river-bank, we reach The First Bridge which crosses the Thames — all previous passages having been made by stepping-stones, laid across in winter and removed in summer. This bridge, which leads from the village of Kemble to that of Ewen, is level with the road, the river flowing through three narrow arches; it is without parapet. Hence, along the banks for a considerable distance, there is no foot-path of any kind; the traveller who would explore its course must cross hedges and ditches, and avoid the main road to Ewen — an assemblage of cottages and farm-houses. And a delicious walk it was, to us, beside the river, — pleasure being augmented by difficulties in the way; the birds were singing blithely in small wood -tufts; the chirp of the grasshopper was gleeful in the meadows; cattle ruminated, standing knee-deep in adjacent pools; the bee was busy among the clover, and, ever and anon, darted across the stream the rapid king-fisher, the sun gleaming upon his garb of brilliant hues. [16-17]

The First Mill on the river and the town of Lechlade

Left: The First Mill. Right: Lechlade Bridge and Church.

Soon after we leave the valley in which the Thames is born, and where its infant wanderings are but promises of strength, the river becomes well defined, and of no inconsiderable breadth and depth; its waters have gathered force, and are turned to profitable uses. A mile or so of pleasant walk along its banks, and we reach The First Mill on THE Thames — the earliest effort to render it subservient to the wants of man, ministering to industry and producing wealth. The mill is sufficiently rude in character to be picturesque: it is in an open court, fronted by an old pigeon-house, and occupied by a pleasant and kindly miller, who reasonably comjtlains that the engine of the canal frequently leaves him without water to move his wheel. He was, however, busy during our visit, and seemed well pleased to aid the artist in his efforts, apparently much interested in the progress of his work. [23]

We approach Lechlade; but, within a mile or so of the town, we pause at a place of much interest; for here the Coln contributes its waters to the Thames, and here terminates that gigantic undertaking — the canal which unites the Severn with the Thames, and which, when steam was thought to be a day-dream of insanity, poured the wealth of many rich districts into the channel that carried it through London to the world. The Coln — a river which the angler loves, for its yield of trout is abundant — rises near Withington, in Gloucestershire, and, passing by Foss Bridge, Bibury, Coln St, Aldwin, and Fairford. . . . [41] We are, however, now at Lechlade, where the Thames is a navigable river, and a sense of loneliness in some degree ceases; — effectually so, as far as Lechlade is concerned, for, as the reader will perceive, its aspect is an antidote to gloom. Lechlade is a very ancient town. It derives its name from a small river that joins the Thames about a mile below its bridge. The Lech is little more than a streamlet, rising in the parish of Hampnot, in the Cotswold district, and passing by Northleach and Eastleach. The proofs of its antiquity are now limited to its fair and interesting church, dedicated to St. Laurence. It is very plain withinside, but stately-looking. It contains no old monuments, with the exception of a brass of a gentleman and lady of the time of Henry VI, and another of a man of the time of Henry VII, Close to the north porch is an interesting relic of the olden time — "a penance stone," on which formerly offenders against the discipline of the church stood enshrouded in a white sheet to do penance. The spire is a pleasant landmark all about. It is now, as it was when Leland wrote, two hundred years ago, "a praty old toune," where those who love quiet may be happy.[46]

Between Radcot Bridge and New Bridge

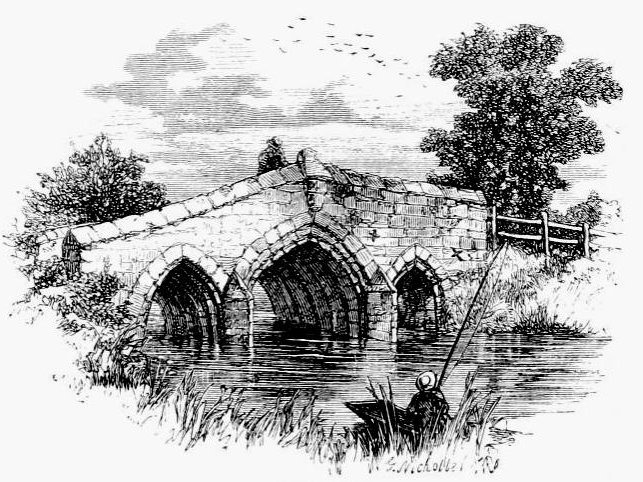

Left: Radcot Bridge. Right: New Bridge.

Our course may be rapid between Radcot Bridge and New Bridge, although the distance is some ten miles; for there is no village along its banks, but one small bridge — Tadpole Bridge — and but one ferry. There are, however, several weirs that act as pathways for foot-passengers; and these weirs break the monotony of the river, afford "rests" to the voyager, and add materially to the picturesque of the scenery — nearly all of them being old and somewhat dilapidated. These are Old Man's weir, Old Nan's weir, Rushy weir, Kent's weir, Ten-foot weir, and Shefford weir: they occur during the first half of the voyage. Rushy weir being the only one that has the adjunct of a lock. A stone's throw from the river, a small cluster of houses, scarcely to be called a village, points out the site of ancient Siford, or Shefford; yet, on this lonely and isolated spot, now apparent!y far removed from human [54] intercourse, the great Alfred held one of his earliest parliaments. "There sate, at Siford, many thanes, many bishops, and many learned men, proud earls and awful knights. There was Earl Alfric, very learned in the law, and Alfred, England's herdsman — England's darling. He was king in England. . .[53-54]

Arrived at New Bridge, we again pause awhile to look around us — to ponder and reflect. The neighbourhood is unchanged since Leland described it as "lying in low meadows, often overflown by rage of rain:" a small inn stands on the Berkshire side, and a busy mill on that of Oxfordshire; in the time of the venerable historian, there was here "a fayre mylle a prow lengthe of;" and it is probable a hostel also entertained the wayfarer. Age has preserved only the bridge, which was "new" six centuries ago,and is now, we believe, the oldest of all that span the river . . . A short distance below, the Windrush contributes its waters to the Thames, — one of the prettiest and most pleasant of English rivers; it rises among the hills of Cotswold, near Guiting, and, passing through Bourton-on-the-Water, Burford, Minster-Lovel, Witney (so long and still famous for its blankets), fertilizes and flourishes rich vales, quiet villages, and prosperous towns; having done its duty, and received grateful homage on its way, it is lost for ever — absorbed into the bosom of the great father.

Drayton, in his "Poly-Olbion," tells, in his own peculiar manner, the tale of these small rivers which swell the infant stream, describing them as handmaidens, anxious —

" — to guide

Queen Isis on her way, ere she receive her traine.

Clear Colne and lively Leech have down from Cotswold's plain,

At Lechlade linking hands, come likewise to support

The mother of great Thames. When, seeing the resort,

From Cotswold Windrush scoweres; and with herself doth cast

The train to overtake; and therefore hies her fast

Through the Oxfordian fields; when (as the last of all

Those tioods that into Thames out of our Cotswold fall.

And farthest unto the north) bright Einlode forth doth beare." [55]

The Weirs

Again the locks and weirs pleasantly and profitably bar our progress — the principal of these are Langley's weir and the Ark weir — until we reach the ferry, which continues the road between the village of Cumnoi' and that of Stanton Harcourt — the former in Berkshire, the latter in Oxfordshire — each being distant about two miles from the river-side. [55]

Hart's Weir

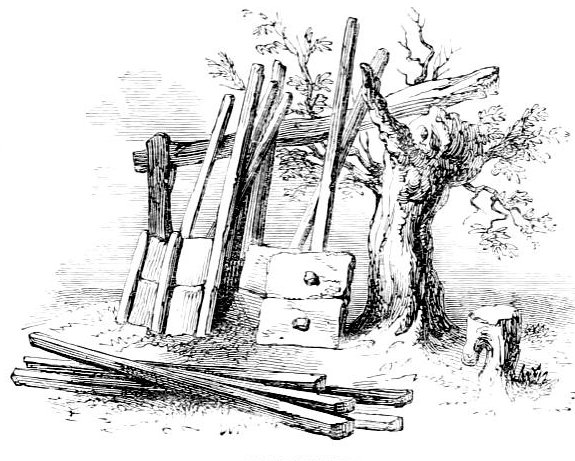

Sometimes the weir is associated with the lock; but, generally, far up the river, where the stream is neither broad nor deep, the weir stands alone. We shall have occasion hereafter to picture them in combination. The weirs are artificial dams, or Lanks, carried across the river in order to pen np the water to a certain height, for the services of the mill, the fishery, and the navigation. A large range of framework rises from the bed of the river; this supports a number of flood-gates sliding in grooves, and connected with a sill in the bottom. Our engraving represents a group of these flood-gates as they were drawn upon land, and resting against the support rudely constructed for them beside Hart's weir. They are thus used: — The square piles in the foreground are first struck at regular distances in the sill under water: between each of these one of the gates is placed by means of the pole attached to it — the boards completely stopping the space, and forming a dam across the river. Two forms of dams are used: one with the board full upon the centre of the piles, and secured to them by strong plugs, over which the boat-hook is sometimes passed to aid lifting; the other has the water-board on one side, with a groove attached to it. Both of these are shown in the cut, as well as the rude stay for the rope of a barge to pass through, and which is generally formed of the branch of a tree. Such arc the usual accompaniments of a weir in the upper Thames. When these dams, or paddles, are drawn up, the whole body of the stream, being collected into a narrow space, rushes through with great rapidity, and gives a temporary depth to the shallows, or, by the power of the current, forces the barges over them. . . . [55-56]

Left: Weir Paddles. Right: Bablock Hithe Ferry.

The weir is ever picturesque, for the water is always forcing its way through or over it — sometimes in a huge sheet, forming a strikingcascade, at other times dribbling through with a not unphasing melody. As we have elsewhere observed, there is usually a cottage close beside the weir, for the accommodation of the weir-keeper; generally this is a public-house, pleasantly diversifying the scenery, and not the less so because often rugged and old. 57

Related Material

Bibliography

Hall, Mr. and Mrs. S. C. The Book of the Thames from its Rise to its Fall. London: Arthur Hall, Virtue, and Cp., 1959. Internet Archive version of a copy in the William and Mary Darlington Memorial Libray, the University of Pittsburgh. Web. 10 March 2012.

Last modified 10 March 2012