The First Sittings

n the summer of 1892, an aspiring artists' model, Mary Lloyd, wrote to Frederic Leighton at his studio house in Holland Park Road to enquire about the possibility of work. This approach would lead to her becoming the inspiration not only for a number of Leighton's major late works, but also for those of his great friend and associate, John Everett Millais and a number of other artists in their circle. Very different in personality and temperament, the two men were equal in prominence in the late Victorian art world. Both were in the last few years of their careers and contemplating painting the subjects closest to their hearts, sharply aware of their mortality.

Mary Lloyd was born on 23 August 1863. A press report in the 1930s stated that she had grown up in luxury, the daughter of a prosperous Shropshire Squire. In her late 20s, as an unmarried woman dependent on her father, who had lost all his money, she now found herself in the unexpected position of having to earn her own living. She then took an unusual step for a woman of her age and class: she chose to come to London to try her luck as an artists' model. She was unusual in another respect, too: besides being working class, most professional models started in their teens. But modelling would certainly have been a more exciting and remunerative option than others open to Mary, such as employment as a governess or Lady's Companion. What her father may have felt about this unusual move we do not know.

Mary decided to go straight to the top. Leighton was not only one of the most prominent artists of the day, he was also President of the Royal Academy. Mary's letter was answered by Leighton's Secretary, John Underhill, inviting her to come for an interview on Sunday 24th July at 9 a.m. and telling her that she might have to walk, presumably due to lack of public transport on a Sunday morning. As Mary was living near Regents Park at the time, this would have been quite a trek. Underhill's letter is the earliest documentary evidence we have related to Mary's career.

Left: Engraving of G. F. Watts's portrait of Leighton, from the Magazine of Art (1888). Right: Leighton's studio from Mrs Andrew Lang's "Sir Frederick Leighton, PRA..." (1886). [Click on all the images for more information about them, and to see larger versions.]

The interview was a success. Leighton was evidently happy with her appearance and manner and she was contacted twelve days later to come for sittings on the 8th and 9th of August. These were to be the first of many to take place over the following three and a half years.

That Summer, Leighton, at 62, was pondering subjects for paintings for the Royal Academy exhibition in 1893. Up until this time, the models for his major pictures had been the four Dene sisters, in particular the eldest, Dorothy. Not only were these women artists' models, they were now also actresses. Leighton had financed and encouraged Dorothy's transition to the stage and enthusiastically supported her theatrical appearances. By 1892, Dorothy was putting all her energies into her stage career, undertaking arduous theatrical tours not only in the provinces but also in America. She was also prone to bouts of ill health, so not as available to pose for Leighton as before. Nor would he have wished to place any strain on her. As a "Leading Lady," integrating into cultivated Victorian society, Dorothy may have distanced herself from the less prestigious role of artist's model.

Leighton was therefore in need of new inspiration. Mary Lloyd's appearance, with a clearly delineated nose, jaw and eyebrows, creamy skin and a cascade of dark, wavy hair, would have set her apart from the more delicately featured, fair-haired Dene sisters, and made her ideal for strong, classical figures. Indeed, it was her distinctive profile that inspired many of the artists with whom she would go on to work. Mary modelled solely "for the head and hands," meaning she did not pose nude and so could claim to be "respectable." As Leighton often worked from drawings for ideas for pictures made years before or used models other than his muse of the moment for life studies, this would not have been a problem.

The Academy, 1893

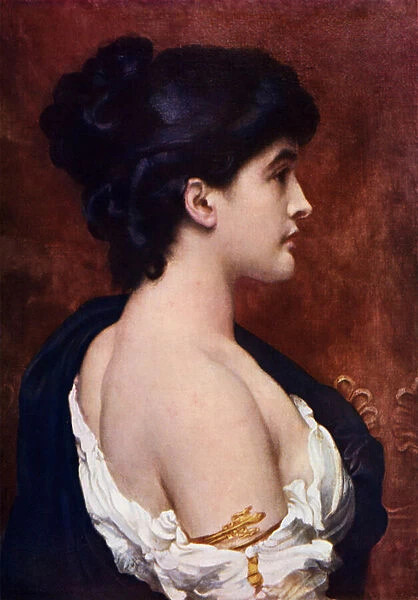

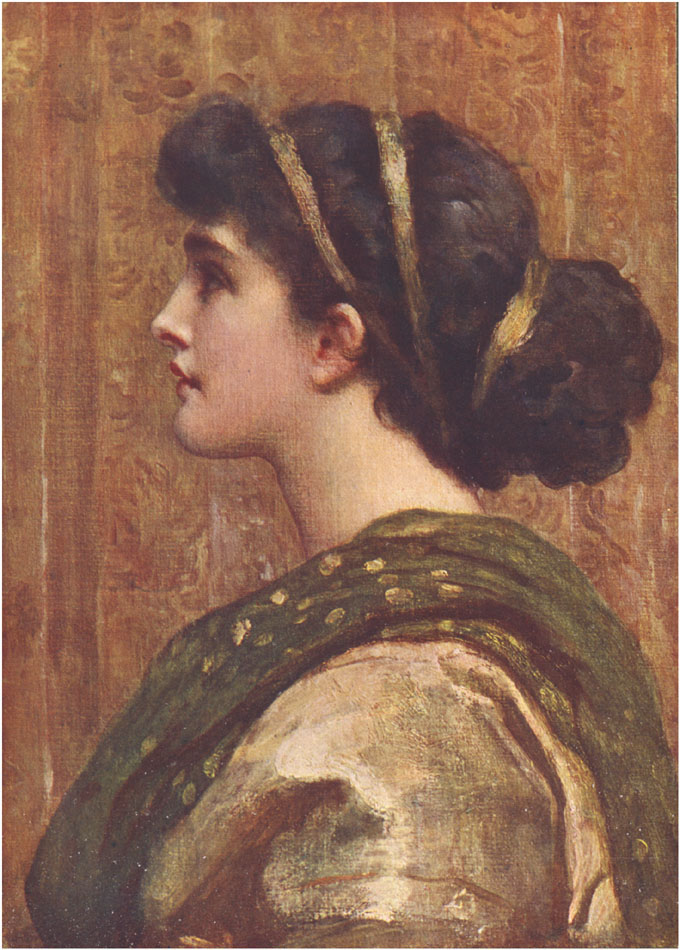

Left: Leighton's Atalanta (1893). Right: Leighton's Corinna of Tanagra (1893).

Leighton's first pictures using Mary as the sole model were two Greek subjects - Atalanta (private collection) and Corinna of Tanagra (Leighton House Museum). These he began in autumn 1892, continuing to February 1893 when Mary's attendance at his studio is recorded in Leighton's appointments diary for 1893, his only diary to survive.

The picture of Atalanta shows the independent, fleet-footed nymph, follower of the virginal hunter-goddess, Diana, who could out-run her suitors and so avoid marriage. Leighton depicted Mary bust-length, facing to the right, wearing a white Greek chiton, her thick, dark hair swept up into a chignon, a gold bracelet clasping her bare upper arm. Emilie Russell Barrington, in her biography of Leighton (Life and Letters of Sir Frederic Leighton, 1906), would single out this picture for special mention, writing:

Atalanta may be noted, perhaps, as the strongest work achieved by Leighton. Here is "enormous power," though shown on a comparatively small canvas. For noble beauty of the Pheidian type in the grand and simple pose and modelling of the throat and shoulder, it would be difficult to find its peer in Modern Art, and yet it was only the worthy record of the beauty of an English girl. [II: 262]

Emilie Barrington does not name the model, though, as a neighbour and frequent visitor to Leighton's studio, she must have known Mary's identity as the very interesting newcomer.

Leighton's Head of a Young Girl (1893).

A head, similar to the Atalanta, but facing left rather than right, wearing richly coloured draperies and with a gold fillet encircling her hair, was given to Prince George (later George V) and Princess Mary of Teck as a wedding gift in June 1893, entitled Head of a Young Girl (Royal Collection). Leighton, like a number of his fellow artists, was very particular about the garments in which he dressed his models. He had a career-long fascination with intricately pleated classical draperies for which he used a specific type of muslin fabric. When he wanted a richer, more colourful effect, such as for this royal wedding gift, it was simply a matter of changing the colour of the pigment used to paint the garment rather than selecting a different, coloured fabric for the model's costume. Leighton's gift was illustrated in colour, immediately after his portrait, at the beginning of Volume II of Barrington's biography giving the picture some prominence in her account of the artist's career.

The half-length figure, Corinna of Tanagra, the lyric poet of mythological narratives, said to have beaten the renowned Pindar in competition, leans on a kithara, the stringed instrument on which she would have accompanied her recitation of her poetry. Mary is shown full-face, gazing out, enigmatic and challenging, from the undefined background gloom of the picture. The aedicular frame Leighton chose for the work, with its Doric columns and classical motifs, gives the effect of the poet appearing in the portico of a Greek temple. Mary later remembered sitting by the fireside in Leighton's studio as he painted the picture and noted "How kind he was." The picture hangs today in the Leighton House Studio.

Leighton submitted these two pictures to the Academy for exhibition in 1893. After the end of the Season, he left for his accustomed overseas travels from 9 August until 5 November 1893. Mary was summoned immediately upon his return, coming to the studio on the 7 November.

Links to Other Parts

- Part II: Sitting for Millais; Mary and the Royal Academy Exhibition of 1894

- Part III: Mary and the Royal Academy Exhibition of 1895

- Part IV: After Leighton and Millais: 1896

- Part V: Later Appearances; the Final Years; Bibliography

Created 25 September 2024