The following excerpts are from the third chapter of Mrs Lionel Birch's book, Stanhope A. Forbes, ARA, and Elizabeth Stanhope Forbes, ARWS, published in 1906, pp. 25-30. See bibliography for full details. The passages are consecutive, but a division and sub-headings have been added for clarity. The illustrations are from the book. Click on them to enlarge them, and for more information about them.

N an article entitled “A Newlyn Retrospect,” written for an interesting but too short-lived periodical, The Cornish Magazine, of which Mr. A. T. Quiller-Couch — that brilliant writer and good Cornishman — was editor, Mr. Stanhope Forbes thus tells of his first entry into the village which he and his friends were to render famous.

From The Cornish Magazine

I had come from France and, wandering down into Cornwall, came one spring morning along that dusty road by which Newlyn is approached from Penzance. Little did I think that the cluster of grey-roofed houses which I saw before me against the hillside would be my home for so many years.

The Slip, by Stanhope A. Forbes (Birch, frontispiece).

What lodestone of artistic metal the place contains I know not; but its effects were strongly felt in the studios of Paris and Ant¬ werp particularly, by a number of young English painters studying there, who just about then, by some common impulse, seemed drawn towards this corner of their native land.

We cannot claim to have been the dis¬ coverers of this artistic Klondyke ; and, in¬ deed, found already settled there many old acquaintances, fellow students of the Quartier Latin and elsewhere. It is difficult to say who was the original settler, for painters seem always to have known of the attractions of [25/26] the place; but about the time I am speaking of, the tide set strongly into Mount’s Bay, and it is curious to think of the number of painters, many of whom have attained distinction, who visited this coast about then. There are plenty of names amongst them which are still, and I hope will long be, associated with Newlyn, and the beauty of this fair district, which charmed us from the first, has not lost its power, and holds us still.

************In an address read two years afterwards before the Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society of Falmouth the painter pursues his argument:—

Address to the Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society of Falmouth

It will always be a debatable point how far it is necessary and wise for a painter to live and work in cities, in close touch with his contemporaries. I am perpetually being told that to London we must go, that it is the inevitable fate in store ; yet I cannot but think that it was a healthy and sensible movement in Art, the formation of these little colonies of painters, clustering together in charming rural districts, whose beauty in¬ spired their work and afforded them abundant material. I would not quarrel with those who would have us forsake all this, and bid us return within that charmed four-mile radius of brick and stone. Their anxiety to lure us back is flattering to our vanity, but speaking as one who loves the country, I have so often seen the great city open its voracious maw to swallow up my friends, that I own I dread their arguments. I am the first to admit that interchange of views and mutual counsel are essential in our profession. Artists are by nature and temperament gregarious beings [26/27], and must congregate together. They must and will hang together, as their pictures do on the walls of exhibitions. To me these same groups appear to solve the problem very satis¬ factorily, and afford that happy solution, by which the painter can live the quiet life of the country without too much isolating him¬ self and losing the companionship of his fellow workers, which is almost a prime necessity of his existence. The brotherhood of the palette is a strong bond, and should unite us very closely. There are few painters, I think, who will not have to confess that the society they take most pleasure in is that of their brother artists, for it is a charming and fascinating country, this little Bohemia of ours, in which we are privileged to dwell. Not very rich, perhaps, or influential, but its inhabitants are happy, simple, and contented. You must not envy us our kingdom, nor grudge us our domain.

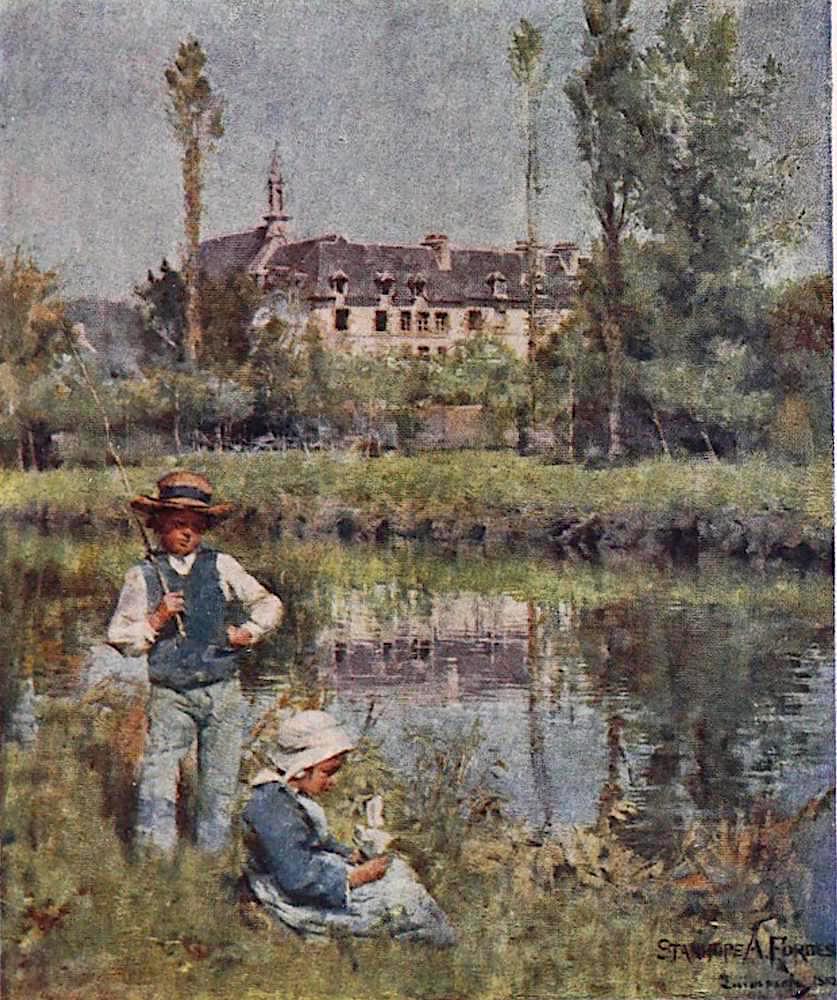

The Convent by Stanhope A. Forbes (Birch, facing p. 22).

It was thus that these colonies or schools, which have become more or less established institutions in Cornwall, were formed. These settlers, these artistic outlanders, journeyed down to this Rand district of the West, where the treasure they sought was to be found in such profusion. And they met with a kindly reception at the hands of the natives, fortunately provoking no resentment and creating no ill-feeling. They carried on their occupation in full view of all; and it seemed a peaceful and inoffensive one, affording the onlookers some little amusement, not unmixed, perhaps, with pity. A simple and harmless folk these strangers, whose wealth and worldly possessions were not such as to arouse cupidity, or to awaken the feelings of envy and covetousness. [27/28]

They dug no ugly mine pits, nor did they erect huge factories for the manufacture of their wares; and the only chimney that seemed indispensable to their work emitted nothing worse than the fragrant odour of tobacco as they puffed away over their somewhat curious and singular industry. Thus humoured by a kindly-disposed set of inhabitants, their oddities pardoned and their whims excused, they increased and multiplied and became almost as closely identified with the Duchy as its famous pilchards, or that celebrated rock of St. Michael hard by where they had elected to dwell.

Here every corner was a picture, and, more important from the point of view of the figure-painter, the people seemed to fall naturally into their places, and to harmonise with their surroundings. Coming as I had done from Brittany, a country where a beautiful national costume has been handed down from generation to generation, it was always something of a shock to find in England so little to interest one in the dress of the inhabitants. Most certainly for a wave of realism, the end of the nineteenth century seemed a most inopportune moment. It is useless to abuse our national costume. We are all agreed that it is in every way unattractive, and none the less we cling to it. The Englishman loves his hideous disguise, and nothing but the force of circumstances will ever compel him to forego it. I am convinced that if fishermen could manage their boats and trim their sails under such condi¬ tions, they would resolutely go to sea in tall silk hats and black frock coats. Fortunately, such garments are found inconvenient, and [28/29] they are obliged to don their quaint sou’-westers and duck frocks, and all the rest of the picturesque attire which one is always struck with in strolling through a fishing village.

All these things delighted me from the first, for here seemed to be a spot where the figures did not clash with the sentiment of the place, making one sigh for the good old days of picturesque costume, but actually seemed appropriate and just. For not only the dress, but its wearers were alike weather-stained, and tanned into harmony by the sun and the salt wind, so that the whole scene was in keeping and of one piece. Nature has not lavished all her care on the landscape here about, but has built up a race of people well knit and comely, fit inhabitants of such a region. Models, that prime necessity of a figure-painter, were to be found here, as good as one could desire; and I think I can claim to have been one of the foremost in accustoming the good folk of the district to the somewhat eccentric conduct which the out-of-door painter in his zeal affects.

It may seem somewhat of a paradox, but I have often found the success of the picture to be in inverse ratio to the degree of comfort in which it has been produced. I scarcely like to advance the theory that painting is more successful when carried on in discomfort, and with everything conspiring to wreck it, for fear of rendering tenantless those comfortable studios the luxury of which my good friends in the Melbury Road and St. John’s Wood so much enjoy. At the same time, I do seriously think that there is a certain quality of deliberateness most valuable in painting, which is un-[29/30]doubtedly encouraged where the conditions of one’s work are not over and above enjoyable. In his eagerness to get the work done, the painter is careful not to waste time or linger over the job, but to go straight at the mark and make every touch tell. I have never painted with such directness as on those fortunately rare occasions when I have worked at sea, and I have carried large pictures right through to the last touch in smithies, stable-sheds, and amid all sorts of queer surroundings under conditions which when starting seemed absolutely hopeless and prohibitive. It is much discussed whether it is better to work directly from Nature or to make innumerable studies or notes and paint the picture from them. I believe no rule can be laid down, and that it is entirely a matter of individual temperament. My own custom has always been to work as much as possible on the spot, and practice has taught me that this offers certain advantages over any other method. There is a quality of freshness most difficult of attainment by any other course, and which one is too apt to lose when the work is brought into the studio for completion.

Bibliography

Birch, Mrs Lionel. Stanhope A. Forbes, ARA, and Elizabeth Stanhope Forbes, ARWS. London: Cassell, 1906. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Kahl/Austin Foundation. Web. 23 February 2021.

Created 23 February 2021