The illustrations here, except for the first, come from our own website. Click on them to enlarge them and for more information about them. — JB

Pre-Raphaelitism was always a multifaceted movement, producing poetry, painting, illustrations, sculpture, stained glass, tapestries and furniture. The subtitle of the Pre-Raphaelites’ journal, The Germ (1850), makes the Brothers’ position clear as they projected their ‘Thoughts towards Nature in poetry, literature and art’, a dictum which was adopted by several generations of artists, writers and designers. But Pre-Raphaelitism was not only a matter of multiple production: more importantly, it was interdisciplinary, fusing and blending the arts in diverse and experimental ways.

For example, much of the painting was literary, depicting narratives drawn from Shakespeare, the Romantics, Dante and other contemporary sources; at the same time, Pre-Raphaelite art was literary in the sense that it had the textual density of literature, using semiologies that demanded to be ‘read’ in parallel with the process of decoding written language. On the other hand, the poetry deployed pictorial techniques, of ‘painting in words’, recreating the sensory intensity and detail of the canvases, and there were many other points of convergence and overlap: poems and quotations were incorporated into the paintings’ frames, Pre-Raphaelite illustration visualized poetry, and verse was inspired by works of art, recreating the ekphrastic effects of painterly stillness.

Such intermingling is a central facet of the PRB’s aesthetics, and it is taken up in this collection of stimulating poems, The Presence and the Dream: A Decade of The Pre-Raphaelite Society Poetry Prize. Edited by Serena Trowbridge and Sarah Doyle, the poems contained in this small, attractive book are largely concerned with the process of responding to visual art, with the idea of interconnection vividly depicted in the clasped hands, drawn from one of Rossetti’s paintings, on the front cover. Some of the most famous and resonant images are taken for inspiration, among them Dante Rossetti’s How They Met Themselves, William Holman Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience, and Ford Madox Brown’s An English Autumn Afternoon. These pictures, and several others, are the subject of imaginative interpretation – providing a starting point for the writing of new works of literary art. At the same time, other poems imagine the lives of those involved in the Pre-Raphaelite drama, among them William Morris, Rossetti and the original Brothers, Effie Ruskin and Elizabeth Siddal. In every case, the writers provide a stimulating perspective, by turns amusing and profound, on the characters who created the works of this avant-garde movement or were represented within them.

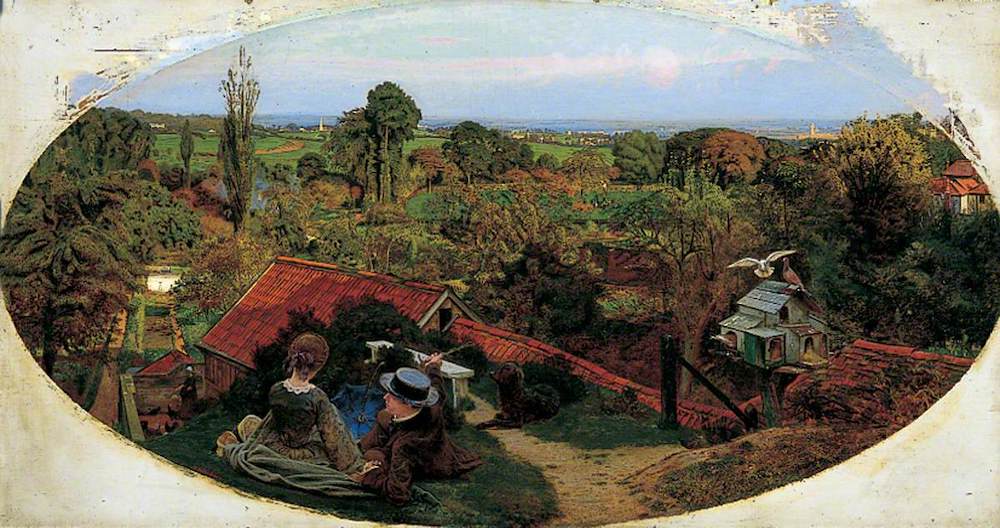

Three of the works that inspired the poems. Left to right: (a) William Holman Hunt's Awakening Conscience, which inspired Amanda Oosthuizen's 'Bells and Marigolds', (b) Ford Madox Brown’s An English Autumn Afternoon, which inspired Sarah Doyle's 'Greenscape', and (c) Rossetti's Astarte Syriaca, which inspired one of Doyle's 'Impressions of Jane'.

Among the most interesting and accomplished poems are by Sarah Doyle, the Society’s poet-in-residence. Especially intriguing is the series of ‘Impressions of Jane’ which already appears on the Victorian Web. Tracing Jane Morris’s appearance in five of Rossetti’s portraits, Doyle imagines what the sitter, re-cast as a mythological or literary subject, might say as she reflects on her marriage to Morris and her relationship with Rossetti. The main focus is the contrast, often ironic, between the passivity of the pictured heroine and the flesh and blood woman who models the image. This ‘real’ Jane is terse, tart, canny, bored, outspoken, amusing, resentful, wearied and simply oppressed by her objectification: in ‘Proserpine’ she complains that ‘my mouth was never as red as this’ and in ‘Astarte Syriaca’ she proclaims ‘I cast no spells, but simply bore/another pose, another’s name’ (35). Much has been written about the male Pre-Raphaelites’ commodification of their female subjects, but Doyle re-instates Jane as far more than a blank screen for the painter’s projected vision. The refrain, ‘Do not be fooled by all you see’, is varied to emphasise her knowingness, a position devastatingly expressed in the final lines of ‘The Daydream’:

For this is not my narrative, And these are someone else’s dreams. Do not be fooled by all you see. I am not here. This is not me (36).

Not only a bold reassertion of the person inscribed in the painted surface, this is a profound questioning of the nature of representation, and reminds us that Rossetti’s portraits can never be described in traditional terms.

Doyle’s iconoclasm features in several of her poems, in each case exploring the psychology of the main players. Her characteristic technique, as in ‘Impressions of Jane’ – which turn out to be hers, not Rossetti’s – is to endow the participants in a painted image with their own voices. ‘How we met ourselves’, a riff on Rossetti’s How They Met Themselves (1864, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge), is a troubling rediscovery of a strange and troubling design, immersing the reader in the wanderers’ nightmarish contemplation of their dopplegangers. The poem, like the image, is focused on doubling and Doyle cleverly writes the equivalent of Rossetti’s mirroring, using a ‘specular’ technique, she explains in the notes, with repeated and inverted lines being used to convey ‘duplication, reflection, and distortion’ (68). What is most unsettling, though, is Doyle’s manipulation of the pronouns, embodying an encounter in which there is no ‘I’, only ‘we, ours, they’. The effect, in true Freudian manner, is uncanny, the collapse of the heimlich into the unheimlich, the one into the double, the known into the semi-known, leaving the characters ‘Afraid to comprehend the strange yet familiar shapes’. By turns ‘thrilling’ and ‘searching’, ‘ghastly’ and ‘twining’ (48), Doyle’s poem powerfully extends Rossetti’s bizarre contemplation of entangled identities.

The work that inspired Wendy Holborow's poem, 'The Noble Working Men: The Navvies': Madox Brown's Work.

Doyle takes us far into Rossetti’s mindscapes, but several poems in the collection celebrate the Pre-Raphaelites’ engagement with the ‘real’ world. Wendy Holborow imagines the lives of ‘The Noble Working Men’, the navvies digging the hole in Madox Brown’s Work (1863, Birmingham Art Gallery). Holborow speculates on the circumstances of these idealized men, filling in their back-story while characterizing each of them in sharply-observed nuance. Of ‘The Shoveller’, for example, she wonders how much he knows of his situation: has he considered how ‘ticking time’ could ‘leave his wife bereft’ if he ‘develops breathing difficulties later on’ and is unable to work? (40). Holborow’s musings convert the painting into a Victorian novel, and like Doyle, questions the relationship between the painting and its creator; though based on real people, each has been captured in time, an idea of working class men, rather than the men themselves.

Other poets aim to recapture the Pre-Raphaelites’ ingestion of the phenomenal world in the form of vivid sensory images as they attempted to enshrine ‘nature’ in vivid details, lights and colours. The original Victorian writers practised ‘painting in words’, and so do the contributors to this collection; the thingness, brightness and here-and-now-ness of Pre-Raphaelitism is given another dimension. Doyle’s description of Brown’s English Autumn Afternoon (1854, Birmingham Art Gallery) in ‘Greenscape’ exemplifies this approach with its evocation of colours and forms, a rich field of ‘Terracotta rooftops’ and the ‘horizon’s/Mists silvering to verdigris’ (58); Nicola Warwick’s ‘Rose of May’ is likewise a palette of nature re-catalogued, a combination of bees and woodlarks and ‘scarlet bowls of poppies’ (50), nature turned vision as Ophelia steps into the water, just a moment before she floats to her death in Millais’s famous painting. Victorian critics remarked on the Pre-Raphaelites’ paintings being all-seeing, as if looking without the capacity to blink, and several of these poems have a dazzling effect.

Just as intriguing are the poems about the people. Andrea Small writes a touching reflection on Euphemia Gray’s sterile marriage to Ruskin in ‘Effie’. Seen from Effie’s point of view, it reveals her frustration as she observes how the love that should have been directed to her is reserved for his notebook and writing equipment. ‘I swear’, laments Euphemia, that she would not be surprised ‘if he sang them a lullaby’; nor would she be surprised if he laid his book in a ‘cradle’ like a ‘newborn’ (54). Things have taken over from emotions, and Ruskin makes love to his work when he should have been making love to his wife. His sexual inadequacy is revealed in the ironic transference of the nurturing imagery – with no chance that this husband could father a child.

The inspiration for Emma Purshouse's 'Christina Responds Badly to Criticism', Christina Rossetti in a Tantrum, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

This is a delicate, mournful, tender poem, and the same can be said of the poems offering half-veiled glimpses of members of the coterie. Shelley Roche-Jacques presents a heart-rending vision of Elizabeth Siddal in ‘From the Memoir of Georgiana Burne-Jones’. The narrator is Georgiana, who tries hard to remember some vivid memory of Rossetti’s muse, but all she can recall is a vision of delicate ephemerality, a woman who seems to exist in a minor key, a ghostly presence of ‘Rose petals … beneath the skin’ (32), and an obvious mismatch with the husband who boorishly declares his bliss. Yet there is genuine love in the poems commemorating William Morris. In Deborah Harvey’s ‘This Serviceable Ghost’ the great man is remembered as a benign presence, haunting Kelmscott Manor, his overcoat still hanging on the ‘north hall door’ (21); and in ‘Wallpaper Man (It’s Over)’ Rosie Miles affectionately dismisses him at the completion of her doctoral thesis. ‘Spellbound for too long’ (16), she realizes the limits of admiration; we can love the Pre-Raphaelites too much. A corrective is offered in the form of Emma Purshouse’s ‘Christina Responds Badly to Criticism’ as the poet reimagines the writer’s tantrum in one of her brother’s droll caricatures. Surrounded by the vandalized furniture and curtains, it is only the ornamental elephant that decides to stay ‘schtum’ (25) and avoid her ire: an amusing treatment of the situation and a reminder that the Pre-Raphaelites – worshipped, mythologized, abstracted, ostracised, converted into an idea – were just as prone to fits of pique and dismay as everyone else; perhaps more.

The Presence and the Dream is a stimulating collection that reaches from the tragic to the absurd, from the unsettling and strange to the quiet reveries of memory and loss. It challenges and it celebrates, and many of its poems are very accomplished pieces of writing, stacked with beautiful imagery and deftly sophisticated in their use of language. The editors have done a sensitive job in representing the many facets of these poetic responses, which, despite their context as celebrations and critiques, can be read autonomously; you don’t have to know about the Pre-Raphaelites to enjoy the poems as poems.

My only cavil is the under-representation of male voices. Most of the verse is by women, and articulates a feminist perspective which foregrounds the female experience of Victorian patriarchy. That certainly needs to be said, but it would have been interesting to hear more from a male perspective – what, for example, might an imagined Ruskin have said to Effie, worn down, perhaps, by her difficult demands to be noticed? Perhaps he was attracted to her, but was afraid? Perhaps Morris was bored with living at Kelmscott – secretly? And perhaps Rossetti would have had something to say to Jane? Those, however, are other stories. They await their re-imagining, and these rich and intriguing poems suggest there is much that can, or might, be said.

Bibliography

[Book under review] The Presence and the Dream: A Decade of the Pre-Raphaelite Society Poetry Prizes. Eds. Serena Trowbridge and Sarah Doyle. Birmingham: The Pre-Raphaelite Society, 2022. Limp covers, pp. 73. ISBN 978-1-3999-2457-3. £10. Available from Serena Trowbridge, Chair of the Pre-Raphaelite Society, at serena.trowbridge@bcu.ac.uk

Created 8 July 2022