This is the first part of the double biography, i.e. the part on James Smetham. It has been transcribed from a copy in the Internet Archive, with some added links and page numbers in square brackets, by Jacqueline Banerjee. [Click on the images to enlarge them and for more information about them.]

ODERN life is so much of a caravanserai that the great public has memory only for the few outstanding figures, whether in literature, science, or art. Thus it is that, though neither has been dead more than about thirty years, James Smetham and Charles Allston Collins are little more than names to the majority of folk. There are several excuses for now linking them in these notes: each had far more than the ordinary amount of earnestness, each, so to say, was on the outskirts of the pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, each was a writer as well as a painter.

The Death of Earl Siward. By James Smetham

. (By permission of Messrs. Shepherd Brothers.)

So few pictures by Smetham appear nowadays in London exhibitions or at Christie’s, that it was something of an event to find, a few months ago, at Messrs. Shepherd’s gallery two works by him, here reproduced. Smetham, the son of a Wesleyan minister, was born at Lately Bridge, Yorkshire, on September 9th, 1821 — six years before William Blake, of whom he wrote so understandingly, died. Maybe he failed to impress himself as a pictorial artist on the public because, as Rossetti told him, in a letter dated 1865: “You comfort yourself with other things, whereas art must be its own comforter, or else comfortless.” Perhaps, on the other hand, it was because instinctively he was a synthesist, on whom the overbearing influence of pre-Raphaelitism operated, after a moment of stimulation, as a disintegrating influence. “Uniformity of minuteness has degraded nine-tenths of even the best pictures,” and though pre-Raphaelitism romanticised detail, that was not Smetham’s pictorial way, probably. Temperamentally he was, without question, an artist. In a letter written to Ruskin, he says that he first awakened to consciousness “in a valley in Yorkshire, out- side the garden gate of my father’s house, when at the age of two years. I have a distinct remembrance of the ecstasy with which I regarded the distant blueness of the hills, and saw the laurels shake in the wind, and felt it lift my hair.” Whether or not the child, so young, had such an experience, will be questioned by many; but, in any case, that was the temper of Smetham’s life: wondering worship at the incommunicable beauty of the world — wonder with, too, a keen sense of the humorous as a corrective. Dissipation of thought, aimlessness, multitudinousness, he held to be among the great faults of our age. “I love the concentrated love of Constable,” he exclaimed; and even Ruskin, the apostle of whole-heartedness, urged him not to work so finely, not to draw so much on his imagination: “Try and do a few easier subjects; the labour of that has been tremendous.” Smetham aimed to build into the fabric of his life, and into the after-life — for, like Blake, he thought of death as no more than the going out of one room into another — each worthy emotion and thought. And he did not scurry over the globe, tourist-fashion, in quest of mental and emotional experience. It was always to hand: in the Bible, in Shakespeare, in our public picture collections, in one Sussex valley. Each day, before taking up the brush, he studied; a wide-margined Bible and like editions of the poets and romancists are said to contain fine pictorial and written comment. As to nature, he knew that the vast is contained in the infinitely small, “the world in a grain of sand.” If, he says, Pascal read one book — Montaigne, “surely one Sussex valley is enough for one life.... When we consider that a whole sky, through all the seasons, is open to one vale, with its stars and sun and moon and clouds of all measures and manners and colours, what more can any mortal mind desire?” One cannot but feel that something of the spirit of Blake was communicated to Smetham when, as teacher of drawing to the students at a Wesleyan college, he wrote: “What if I only mark with chalk on a blackboard the same old diagrams! It is the Creative Truth gleaming white on the Abyss of the Infinite." Whatever may be the value of Smetham’s pictorial legacy, his study of Blake, first published in 1868, and, still more, his “Letters” are a living contribution to literature. In writing there was no pre-Raphaelite influence to deflect him into foreign channels; here he “put to proof art alien to the artist’s,” was his nervous, out- and up-looking, alert and spontaneous self. For one thing, a charming collection of dicta about other painters’ work might be gleaned from the Letters. He apostrophises Van Huysum: “How cool and calm, and cheerful and confident you are, Jan!” [281/82]

Of Millet, there is this: “Wherever Labour stooped in patience, to endless tasks that only yielded bare life, there he was drawn to dwell and watch with the eye of Johnsonian compassion and melancholy.” Turner is, among landscape painters, as in literature is “large-browed Verulam, the king of those who know.” In Cox he discerns the loose, solemn, sweet and windy thought and fluent rapture of Thomson, swelling with the soul of nature and musing praise. In Rembrandt we have “humanity working out its own image in its own way, and with its own material.” And so one might go on, to Crome and “Old Linnell” — “who defied the Academy and the dealers” — to Francis Danby and Fred. Walker, Richard Wilson, Romney, and many more.

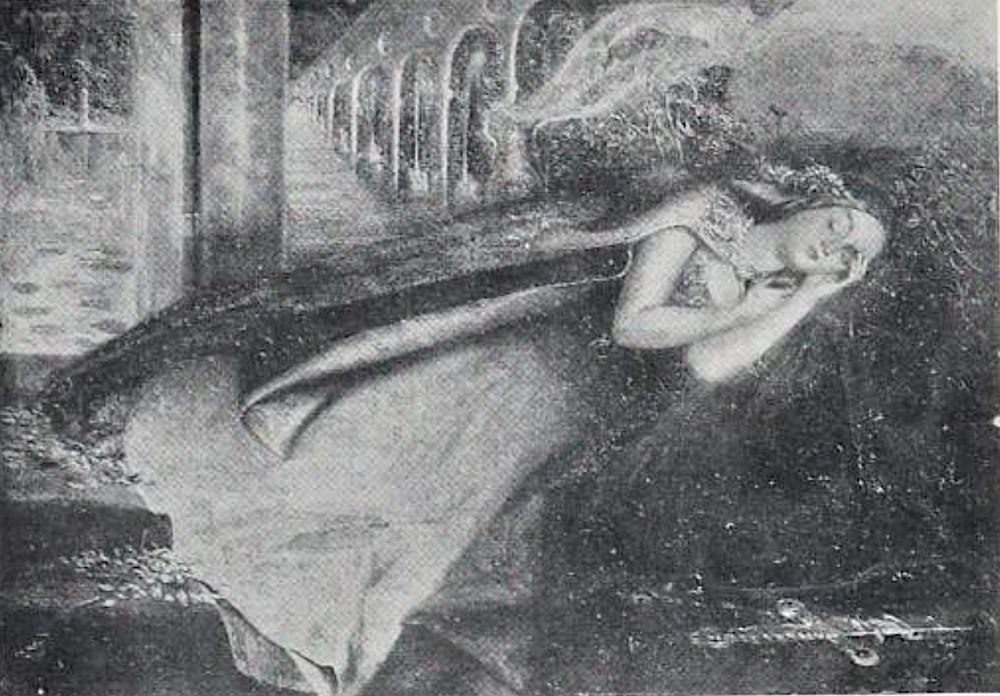

The Enchanted Princess. By James Smetham. (By permission of Messrs. Shepherd Brothers.)

In a “Memoir” prefixed to the “Letters,” Mr. William Davies notes nine pictures only by Smetham, exhibited at the Academy; Mr. Algernon Graves’ “Dictionary,” on the other hand, gives twice that number. The final one, in any case, was the "Hymn of the Last Supper" finished on the 8th of April, 1869, Maunday Thursday, the anniversary, as we commemorate it, of that Supper. It was bought by Mr. J. S. Budgett for 300 gs., and when, prior to sending-in day, it was at Rossetti’s studio for a week, Mr. Watts, one of the hangers at the Academy that year, said of it : “It must be called a great picture, though it is a small one.” In each of the pictures reproduced, the imagination, and not inventiveness merely, has been at work. There is a spell-like quality in "The Enchanted Princess" (p. 282), lying stiffly on a red-covered couch, before a receding arcade whose pillars are of flame-green. The reproduction should be turned upside down, and then compared with the ‘Ophelia’ of Millais, painted in 1851-2, one of the most jewel-like and exquisite pictures in the whole range of British art. "The Death of Eail Siward" (p. 281) commemorates the undaunted passing of Siward the Strong, a Danish follower of Canute, who aided Malcolm Canmore in his unsuccessful attempt to recover from Macbeth, representative of the Celtic party in Scotland, his father’s kingdom. Apprehending the approach of death, the Earl caused himself to be clad in armour, set on his feet, and so sustained “that he might not die crouching like a cow.” Sweetness and Strength support him, the staves of Death’s henchmen — the introduction of whose hands only reminds us of Blake’s ecstatic design of "The Sons of God shouting for joy" — visible to right and left. Onward from 1877 a cloud brooded over the mind of James Smetham, and it did not lift before his death on February 5th, 1889.

Bibliography

“James Smetham and C. Allston Collins." Art Journal 66 (1904): 281-282. Internet Archive. Web. 20 June 2021.

Created 20 June 2021