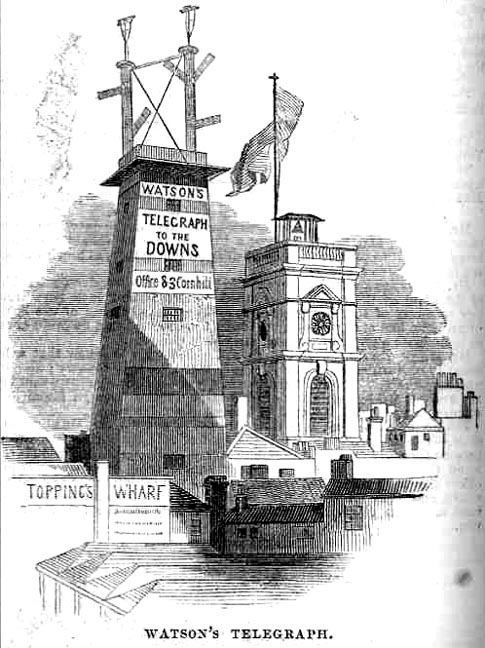

Watson's Telegraph

1842

Engraving

The Illustrated London News

Other images from this article

[See below]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The accompanying text on pages 148-49 extols this technological innovation as enabling Europeans in their efforts to annihilate time and space, a process already begun with the application of the steam engine to travel.

The subject which we have selected for illustration . . . is Watson's Telegraph, established for the service of the mercantile and shipping interest of the United Kingdom--one which, we believe, is not familiar either to our metropolitan or provincial readers, not even along the line of coast where this astonishing contrivance has been established. The title of this machine almost sufficiently explains its use and object as far as the saving of time is concerned, but the simple complexity (if we may say so) of its arrangement is so different from any thing that has been heretofore started to answer the purposes of a telegraph, that we have deemed it necessary, even at risk of encroaching inordinately on our space, to add a rather lengthy letter-press description of the apparatus which the subjoined engraving represents.

As seen from the Borough, Watson's Tower in 1842 was the property of the "Shipping Telegraphic Association." The company's intention, then being carried out, was to construct a system of such towers along the British coastline connected to London to hasten the arrival of specfic information about vessels recently having entered any British port, including the number of passengers, the kind and quantity of cargo, with the expectation that communication of such shipping news (including mention of vessels in distress) might even lead to the saving of lives and property. Such towers ("coast stations") had already been established at Pentland Firth, Peterhead, Flamborough Head, Spurn, Yarmouth, Orfordness, North Foreland, Deal, Reculver, Sheppy, the Needles, and at three harbours on the Isele of Wight, with a line of such stations between London and Deal located on "elevated spots." The key to the line-of-sight system for operating this early telegraph was a "Telegraphic Dictionary" kept at every station. Containing thousands of words, names, phrases, and directions, the operator's handbook had been compiled alphabetically and with great care so that the operative at one station could translate and/or send the names of places and ships, as well as nautical terms: "each one has a number attached to it, which number becomes the symbol in signaling" (p. 148).

It will thus be seen that the telegraphic operation consists, in principle, of the transference from place to place of symbols representing numbers. In this plan the numbers are represented by the position which two or more boards, poles, or arms, are made to assume, with reference one to another; the general principles of which (though not the minute details) may perhaps be understood from the following description.

The main part consists of two vertical masts, about twenty feet apart, and fifty feet high. Two cross-trees or poles are fixed, one near the top of each mast, and two pairs of arms are hinged to the lower part of each mast, one pair above another. There are thus eight arms, which when down in the grooves are invisible at a small distance. When in operation, one arm is capable of projecting sideways in one of three different directions, viz., upwards, inclining downwards, and horizontal. Every arm is managed by means of a wire rope, which passes into the house, and is there moved by a sort of windlass.

The article then explains how various positions signify the numbers 1 through 9 on one pair of lower arms attached to the same mast at equal heights; numbers higher than 9 require the upper pair of arms in combination with the lower. For example, "To indicate such a number as 79, therefore, the two upper arms would incline upwards for 70, and the two lower would incline downwards for 9" (p. 149). Since this system had not proved feasible on board a merchant ship, Watson had substituted a system of thirteen flags of various colours hoisted in various positions, a system already in use in the north of England at the time of writing. Through this system, too, merchant ships could communicate with ships of the Royal Navy.

References

"Telegraph Tower." The Illustrated London News (25 June 1842): 148-49.

Victorian

Web

Telecom-

munications

Periodicals

Ill. London

News

Next

Last modified 27 September 2006