"Lady Journalists. (Third Series)," in the Lady's Pictorial, 9 December 1893 (p.928-929) covers Lady Colin Campbell (née Gertrude Elizabeth Blood; 1857–1911); Mrs. Jack Johnson (née McMaster; the first honorary secretary of the Society of Women Journalists, and a member, 1894/1895–1903/1904; "Ethel" and "Levana"); Mrs Stannard (Henrietta Eliza Vaughan Stannard, née Palmer; 1856–1911; "John Strange Winter"); Mrs. (Eliza) Erskine Clarke (born 1837; aged 74 and a widow living with her daughter Mary Clarke, a painter and artist, in the 1911 census; listed on https://swj1894.org under the name Mrs. R. H. [Richard Henry] Clarke as a member of the Society of Women Journalists, 1894/1895–1910/1911); Mrs. Ada S. (Sarah) Ballin (1863–1906); Mrs. (Blanche de Montmercy) Conyers Morrell (1847–1909). It is illustrated with portraits of Lady Colin Campbell from a photograph by J. Russell and Sons; Mrs. Stannard ("John Strange Winter") from a photograph by Francis Browne; Mrs. Johnson from a photograph by Francis Browne; Mrs. Erskine Clarke from a photograph by J. Russell & Sons; and Mrs. Ballin from a photograph by the London Stereoscopic Co.; Mrs. Conyers Morrell from a photograph by Walery.

[The portraits below are in the original piece, but the decorated initials, bold print and dates for each journalist, endpiece and links have all been added. Thanks to Valerie Fehlbaum, from the Department of English Language and Literature at the Université de Genève (and the author of a biography of Ella Hepworth Dixon) for sharing the scans that served as the basis of these transcripts for readers of the Victorian Web. — Philip Jackson]

ADY COLIN CAMPBELL, is a most indefatigable as well as brilliant journalist, devoted to her work, and doing it with a grace and charm which would be impossible if it were not, in some degree at least, a labour of love. Lady Colin is a familiar figure at "private views" and "first nights," as well as at the majority of social "functions" which come within the category of her journalistic achievements, and, no matter what the nature of the subject to be treated, she never fails to invest it with a literary style that is very attractive, and to make it the means of utilising the store of information which is the result of a liberal education, wide and varied reading, and a cosmopolitan experience of people and places. Lady Colin Campbell is art critic of Vanity Fair and the World, writes those charming and often instructive articles called "A Woman's Walks" in the World, as well as other articles upon social and general subjects, and is a regular contributor to the National Review, the Art Journal, the Saturday Review, and a number of Continental and American periodicals. She has also written a number of short stories, some of which appeared in the pages of the LADY'S PICTORIAL.

rs. Jack Johnson, whose bright and clever style quickly made its mark when, hall a dozen years ago, she first thought of taking up journalistic work as a profession, is a living proof of the fact that the journalist, as well as the poet, is born, not made. For there had been no technical training, and, indeed, little, if any, of that amateur scribbling which is frequently the first symptom of the ailment known as cacoethes scribendi, which so often lingers with its victims to their latest breath, when, upon a certain morning, destined to be memorable in her life-story, she called upon the editress of the Queen, and at once obtained some work on that excellent journal. The tact which is so essential to success in journalism of all vocations stood her in good stead upon this critical occasion, for she did not present herself in the editorial presence armed with rolls or mounds of MSS., as presumptive evidence of her genius, but dressed herself so nicely that her mere appearance proved that she knew something about the subject of all others dear to the readers of a lady's newspaper. This was in Jubilee year, and Mrs. Johnson at once began to gain a good general journalistic experience on the staff of the Queen, and to contribute to its columns in a variety of ways. Then came the launching of Woman, to the very first number of which Mrs. Johnson contributed "Art Notes," and in the third issue of that paper she commenced her series of weekly articles called "Snuggery Small-talk," signed "Ethel," which dealt brightly and with knowledge of all sorts of details connected with dress and fashion: a leaven of journalistic baking powder to relieve other subjects of more serious interest. This continued for two or three years, and while doing this work, which occupied a considerable portion of every day, Mrs. Johnson contributed interviews, chiefly with literary people, to the Woman's Herald, and became a regular contributor to the Gentlewoman. In addition to these onerous duties Mrs. Johnson contrives to find time to contribute short stories and articles upon a variety of social subjects to various periodicals, and writes two London letters for a syndicate of provincial journals, one upon all matters connected with the home, and one upon fashion, under the signature of "Ethel." Mrs. Johnson, before her marriage, was Miss McMaster, a daughter of the representative of an old North of Ireland family, but her mother was an American, which fact may be responsible in a measure for some of the vivacity and lightness of touch which lend a charm to her journalistic work. The first article which Mrs. Johnson ever wrote was upon the subject of ball dresses, yet she is by no means innocent of contributions to the more serious side of feminine journalism, and is cordially interested in every detail of women's work, especially of an artistic and obviously suitable nature, and she was on the sub-committee of the Handicrafts Section of British Women's Work for the Chicago Exhibition. Mrs. Jack Johnson does not claim to have a "mission," but she is invariably interested and sympathetic in all matters connected with the welfare and interests of her sex, and it speaks volumes for her personal tact that she has always "got on well" with other women, in and out of the profession, and gratefully acknowledges that she owes many a good turn to fellow-workers of her own sex.

rs. Stannard, better known to all the world as "John Strange Winter," the author of many bright and breezy novels, some of which were published in the LADY'S PICTORIAL, remarkable for their kindly tone and broad human sympathy, has some very substantial claims to be also included in the ranks of the lady journalists, not only by virtue of the fact that she is intimately associated with the first women's Press Club, but also because she has undertaken journalistic responsibilities and duties of considerable moment in her connection with the weekly journal known as Winter's Weekly. The author of "Bootle's Baby" does not herself consider that she is altogether entitled to be included among the lady journalists of the day, but it may fairly be said that a list in which no reference was made to the first president of the first women's Press Club established in London, would scarcely be complete. The unpretentious Writers' Club — as it is called — which has its premises in Fleet-street, is now a flourishing and helpful institution, and already in search of roomier quarters. Mrs. Stannard is now its treasurer, having declined to serve as president beyond the first year. In that office she was succeeded by H.R.H. Princess Christian.

Mrs. Stannard, some three years since, was adventurous enough to start a penny weekly home magazine. Like nearly all independent journals Winter's Weekly has had many vicissitudes to contend against, but at last seems to have been steered into smooth waters and found a permanent place for itself. It was at one time the only penny paper in the world owned, edited, and published by a popular author, but since its birth it has been followed by numerous "authors' papers"—notably Sala's Journal, Annie S. Swan's magazine The Woman at Home, and Mr Jerome's weekly paper To-Day. As editor of Winter's Weekly Mrs. Stannard has not spared herself—at least a quarter of the matter in the journal being from her pen, in the shape of Answers to Correspondents, Editor's Thoughts, fiction, and numerous special articles. Journalistically, perhaps, her vigorous crusade against the crinoline early in the present year, when she rapidly organised a league of no less than 19,000 ladies, pledged to oppose the threatened revival, is her most notable effort. It is claimed that the prompt expression of hostility thus obtained did much to cause the attempted revival to be abandoned. Mrs. Stannard has kept herself apart from all the distinctively "women's movements" of the day, being, in spite of her strong individuality and robust self-reliance, essentially a domesticated woman. For her a vote and other "women's rights" have no charm; she only asks that sex should bring with it no hindrance to such work as women find themselves able to perform. During the present year Mrs. Stannard has been paid the compliment of being elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. Only one other woman had previously been accorded this honour.

As an author she has been more prolific than any other English authoress of late years, nearly forty novels having been published by her during the eight years she has been prominently before the public. This huge amount of work was preceded by a still larger number of novels issued as serials in the ten years preceding the publication of "Bootle's Baby"—an apprenticeship to the pen which enabled her to take full advantage of the chance of popularity which came to her on the success of that well-known novelette.

Although she has become most favourably known as a writer of singularly well-informed soldier stories, she has recently essayed an entirely different order of novel in "The Soul of the Bishop," a story with a theological interest which met with a varying reception from reviewers, but has exceeded in success any recent story from her pen. Her most recent novelette, "A Man's Man," her ninth Winter's Annual, has been exceptionally successful, no less than three large editions having been exhausted during the first fortnight. Among the Christmas numbers for this year to which she contributes are those of the Illustrated London News, The Queen, English Illustrated Magazine, Hearth and Home, Belgravia, Ludgate Monthly, Lloyd's News, and Winter's Magazine.

Mrs. Stannard was born at York, on January 13th, 1856, daughter of the Rev. H. V. Palmer, rector of St. Margaret's, York, who, before taking orders, was an officer in the Royal Artillery. His father and grandfather were also English officers. Mrs. Stannard was married in 1884, and has three children.

During the last two years she has written a great number of verses, many of which have recently been published as songs with music by Tivadar Nachez, Milton Wellings, J. M. Capel, Hester Carew, and others. Mrs. Stannard is, in truth, a most versatile and successful worker.

rs. Erskine Clarke, who is a thoroughly competent "all-round" journalist, whose work, of whatever nature it may happen to be, is never lacking in pleasant literary style, has had a most usefully varied experience in the pursuit of the profession in which she takes so much delight. Journalism in the case of Mrs. Clarke has always been the turning to practical account of an unmistakable natural taste, and her success has no doubt been largely due to the fact that from first to last she has always been able to do her work con amore—a condition which almost of necessity guarantees that thoroughness which is of so much value to a journalist.

All her life Mrs. Clarke had a very vivid desire to write, but novel writing never commended itself to her, for the simple reason that she could not construct a plot. Moreover, living in the quietest country clerical circles, where Sunday school teaching and church going tilled up the Sundays, and district visiting with a little more church going occupied the week, and there was plenty of domestic sewing and letter writing to be done between whiles, there was neither scope nor opening for literary work. After her marriage, in 1865, to Mr. H. R. Clarke, then of Grove House School, South Hackney, and afterwards of Shanklin College, Isle of Wight, her own children, as well as those of others, had to be attended to, and not till they were pretty well advanced in their education did she find time to try her luck with pen and ink. Her very first work was writing up a set of botanical electros for Messrs. T. V. Partridge and Son, and the next for Cassell and Co. In the course of a year or two Mrs. Clarke went further afield, and was very fortunate with contributions to Fraser's Magazine, and extremely proud when she had an article in the Nineteenth Century.

Journalism, however, was to be her destiny, and the first paper to which she attached herself was the Hornet, long ago defunct, and the second was Pan, a short-lived but good-looking and very smart "society" print. Then Society came out, and from the first or second issue Mrs. Clarke was a regular contributor. She contributed also to the LADY'S PICTORIAL, the Illustrated London News and the Lady, on which latter paper she succeeded Miss Mabel Collins as editress [corrected at the foot of the fifth series: the editress is, in fact, Mrs. McHardy Gooche], and also reviewed books in Vanity Fair. Mrs. Clarke also writes sometimes for the Gentlewoman and Queen, and her eldest daughter, who is a successful artist of the Herkomer School at Bushey, and had a picture well hung just above the lines in this year's Academy, occasionally draws for both papers, and has just illustrated Miss Mabel Collins' story, "The Penalty of Death," in the Lady; and it is very pleasant when mother and daughter can thus work together in illustrated journalism. Mrs. Clarke has also at sundry times written a good deal for the New York Herald and some other American papers. Outside journalism Mrs. Clarke has written little beyond one of the earliest handbooks about Cyprus, which was purchased by a Scotch firm of publishers; a life of Susanna Wesley for the "Eminent Women" series of Messrs. W. H. Allen and Co.; a small life of Handel for Cassell and Co., and a considerable portion of the "New Household Guide" of that firm.

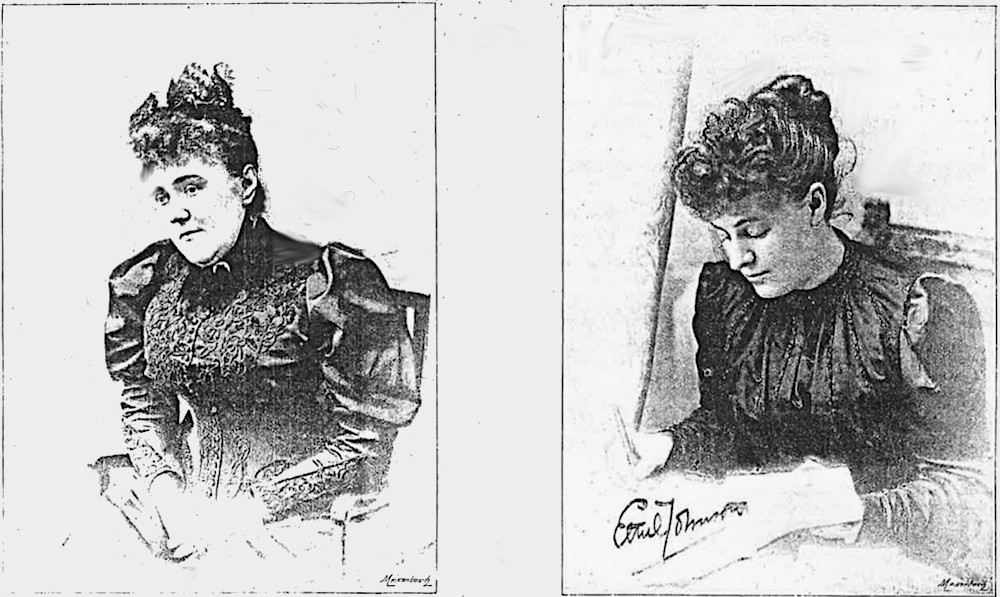

Left: Mrs Stannard ("John Strange Winter"). Right: Mrs. Johnson.

Left to right: (a) Mrs Erskine Clarke. (b) Mrs Ballin. (c) Mrs Conyers Morrell.

rs. Ada S. Ballin, the lady so well known to our readers as the conductor of our "Beauty and the Toilet" columns, was educated at home until the age of sixteen, when she was entered at University College, London, and passed through the college course with dis-/[928/929]tinction, gaining the Hollier Scholarship, value £60, the Fielding Scholarship, value £25, and the Heimann Silver Medal, as well as Prof. Morley's prize for English Composition, awarded in a competition open to the whole college. Distinctions for Languages, Philosophy of Mind, and Logic were also conferred upon her. Shortly after entering college her first signed articles were published, in November, 1883, in Dr. Andrew Wilson's paper, Health, the subject being "How to Clothe Children." Prof. W. Corfield, M.D., under whom she was studying. drew the attention of the medical committee of the International Health Exhibition of 1884, to her writings, whereupon she was asked to deliver a lecture on the subject, which she did at the Exhibition in July, 1884. This lecture attracted much notice owing to Miss Ballin's youth, and the fact that she was the only lady lecturer amongst a large number of medical men, and she was soon appointed one of the lecturers to the National Health Society — a post which she occupied for seven years. She contributed to the Queen a series of articles on "Healthy Dress," which afterwards formed a portion of her well-known book, "The Science of Dress in Theory and Practice," published at the end of 1885 by Messrs. Sampson Low and Co. Miss Ballin was writing for no less than fourteen different magazines and periodicals from 1885 till July, 1887, when she undertook the management of the "Beauty and the Toilet" department of this paper, which she still retains. At the end of that year she published the first number of her paper, Baby: the Mother's Magazine, of which she is both proprietor and editor. This magazine, which is the only one of its kind, is now an established success. Since then Mrs. Ballin has seldom found time to contribute to other papers, as, besides her literary work, she is very much occupied by readers who come from all parts of the world to consult her personally on the various subjects of which she makes special study.

Miss Ballin married in September, 1891, but continues to use her maiden name for professional purposes, merely adding to it the title of Mrs. Her daughter was born in the autumn of 1892, and at the end of that year Mrs. Ballin published her book on "Health and Beauty in Dress," which is now in its third edition. She is at present preparing for publication an important work on "Personal Hygiene." Mrs. Ballin is most thorough and painstaking in her work, a characteristic which, combined with her wide knowledge and experience, constitutes her an authority upon the subjects which she has made her own.

rs. Conyers Morrell, whose excellent taste and wide knowledge of art matters in general and the applied arts in particular are placed at the disposal week by week of the readers of this journal in "The Home" department, has been steeped in aesthetic surroundings from her earliest years, so that good taste is with her equivalent to the culture of an instinct noticeable even in her childhood. Mrs. Conyers Morrell's interest in "art work," more especially in "the antique," dates from very early days, when she travelled constantly on the Continent with her parents, who wintered in Paris in the year of Napoleon's presidency. Her eleventh winter was spent in Rome and Naples, where she was a somewhat spoilt visitor to the studios of Gibson, Miss Hosner, the Count of Syracuse, and others. In London her mother's close intimacy with Sydney Lady Morgan, Geraldine Jewsbury, the S. C. Halls, and many others, gave Mrs. Conyers Morrell a very early interest in writers, and she often thinks of the admiration with which she then regarded Mr. and Mrs. S. C. Hall as editors of the Art Journal, little dreaming that she would one day herself form one of the happy band of journalists. Mrs. Carlyle is also amongst her childhood's memories, and she recalls a schoolroom tea which she enlivened with an account of the auto-da-fé to which she consigned her dolls at the age of six years. On her father's side Mrs. Conyers Morrell recalls with interest his cousin, Dr. Daubiny, the noted scientific writer, and far back on his side she claims connection with that notable needlewoman Adeliza, wife of Henry II., who, en secondes noces, married a "D'Albini["] (Daubiny). On her mother's side Mrs. Conyers Morrell is descended from Sir Richard Clayton, Bart., who was Ambassador in Russia, and in 1797 translated, with notes and annotations, a then somewhat celebrated work, Tentoove's "Genealogie de la famille de Medici." Mrs. Conyers Morrell's first contribution to the press took the form of reports of local matters contributed to the Cheltenham Examiner, the anonymity of which caused much amusement, as no one could make out who the "local" reporter was. Always interested in artistic work of all kinds, Mrs. Conyers Morrell made a special study of china painting, living for some time in "the Potteries" for the purpose of thoroughly mastering the subject, with the result that in 1882 she published a small handbook on china painting, which received the kindly approval of H.I.M. the Empress Frederic, then Crown Princess of Germany, also of H.R.H. Princess Louise Marchioness of Lorne, Messrs. Minton and Co., &c.

Shortly afterwards, the great need experienced by amateurs of really high class designs as copies for their work, impressed itself upon her so strongly that she determined to try and meet this want, and accordingly started, single-handed, the quarterly publication now known as Home Art Work, securing, as time went on, the able assistance of designers such as Messrs. Walter Crane, G. C. Haité, Selwyn Image, Alice Havers, Ellen Vetty, Marion Reid, &c. Home Art Work, now in its tenth year, has been welcomed in all parts of the world. From time to time Mrs. Conyers Morrell has contributed to various papers, The Queen, Weldon's Needlework Series, The Woman's World, &c., and during the editorship of Mr. Oscar Wilde she wrote several papers on historic costumes for that paper, but her chief and probably most congenial work has been the series of papers, mostly upon Antique Needlework, contributed during the past six years to the LADY'S PICTORIAL, upon which she has spared neither trouble nor expense in order to make them as accurate as possible, and for this purpose Mrs. Conyers Morrell has gathered together perhaps one of the largest and most complete collection of specimens of antique needlework owned by any amateur, in addition to a library containing every procurable work, ancient or modern, bearing upon the question. Mrs. Conyers Morrell has been fortunate enough to be able to carry on her work under the happiest conditions, and lives surrounded by the interesting and beautiful things of which it gives her such pleasure to discourse.

Link to Related Material

Created 2 January 2025