The following is the second of several extracts from the author's "A Comic Empire: The Global Expansion of Punch as a Model Publication, 1841-1936," originally published in the International Journal of Comic Art 15/2 (Fall 2013): 6-35. We are grateful to Professor Scully for allowing us to reprint some passages from it here. The image in this part comes from our own website. Please click on it to enlarge it, and for more information about it. — Jacqueline Banerjee

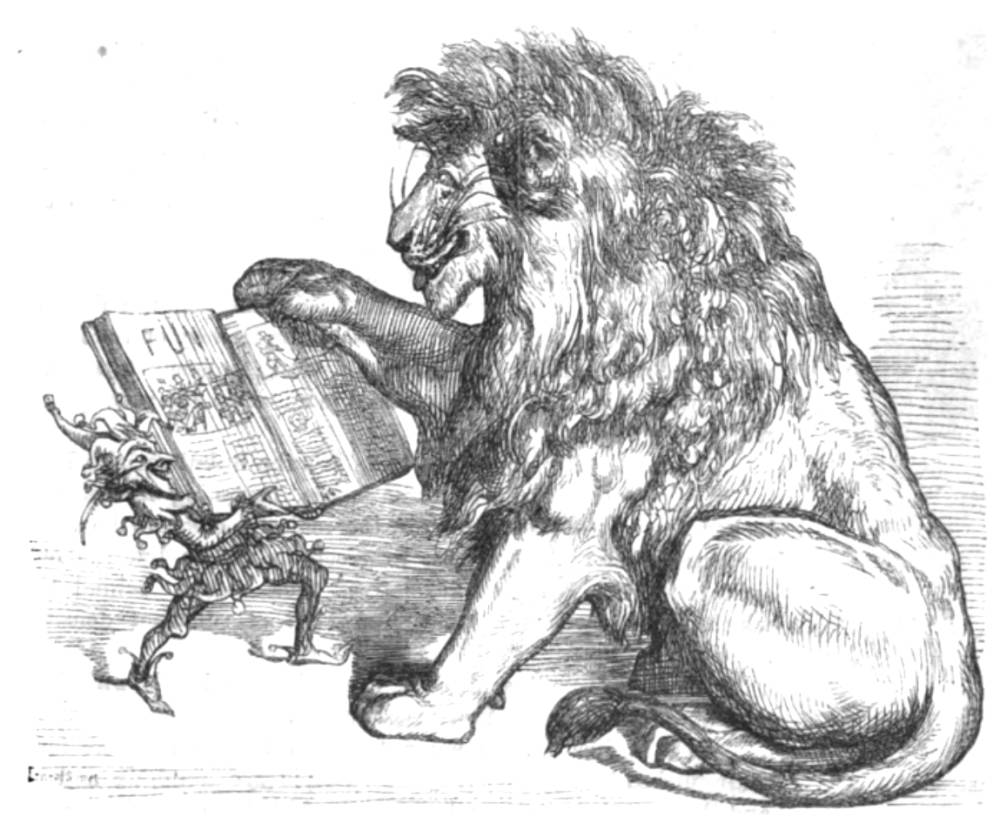

The British lion reading Fun (tailpiece, 1866).

By the 1850s and 1860s in particular, the cartoons of John Tenniel were assumed by many to be as authoritative a guide to the "true" flavor of public opinion in the metropolis as The Times (Morris 248), and Punch spawned a number of metropolitan imitators by those unhappy with its apparent shift in political approach. The playwright Henry J. Byron founded Fun in 1861, to attract the more Liberal and radical readership from which Punch had tended to distance itself (Lauterbach); Charles H. Ross founded Judy; or the London Serio-Comic Journal in 1867 to cater for those of a more "large-C" Conservative persuasion than Punch would often allow for (Scully, British Images of Germany, 136). The implied flattery of these imitators was mostly welcomed by Punch's editors; Punch contributor William Makepeace Thackeray referred to Fun semi-derisively as "Punch," but often called for its latest edition to be passed around the editorial dinner-table in order to match its quality and content (Silver, 12 February and 8 October 1862). As noted above, Henry J. Miller has highlighted the regional British imitators of Punch from Leeds and Birmingham to Belfast and Edinburgh, showing that the adoption and subversion of the Punch model was not merely a phenomenon of the metropolis. Glasgow Punch (1846) and MacPunch (1869) were notable spin-offs from the major cities of Scotland, and Y Punch Cymraeg (1858-1864) sprang up in Holyhead in Wales. There was also a Liverpool Charivari in the Lion (1847-1848), and a Nottingham Charivari (1856), as well as many others which did not directly take the Punch name. These regional Punches are all largely forgotten, and require some further examination to establish their historical significance. Of undisputed significance, however, was another London-based imitator, The Tomahawk of 1867, edited by Arthur à Beckett and Matthew Somerville Morgan, which actually provided Punch with a serious rival. At its peak, it often out-soid Punch itself (à Beckett 174), but the Tomahawk eventually declined in circulation (Ellegård 20), folding in financial and narrowly-avoided social disgrace in 1870 (Scully, "Sex, Art and the Victorian Cartoonist," 309-311). Matt Morgan went across the Atlantic to work for Frank Leslie, and à Beckett later joined the Punch table, only underscoring the importance of Punch in relation to its imitators. That Morgan found a ready home in the United States is a good marker of the trans-Atlantic connections between the British and American satirical presses, and indicates that Punch had imitators far beyond British shores. Though it is hotly disputed — largely because of the nationalist bent of some American comics scholarship (e.g. Dagnes) — the New York-based humor magazines Puck (1871-1918) and Vanity Fair(1859-1863) certainly owed something to the London Charivari (Brown 14-22; Lewin and Huff x). That there were briefly a Southern Punch (1863-1865) in Richmond (Bernath 190-193; Sloane, 268-270; Linneman) and an American Punch (1879-1881) in Boston is a good indicator of the influence of the model of the London original in the former British colonies of the United States; this is especially the case, given the American Punch was a monthly publication that reproduced much of its content from the London Charivari (Mott 267). [12-13]

Related Material

- 1. Punch's Colonial and other imitators

- 3. Maintaining British identity abroad through Punch

- 4. Colonial Charivaris

- 5. An Indian Punch

Bibliography

à Beckett, Arthur William. The à Becketts of "Punch": Memories of Father and Sons. New York: E. P. Button and Company. 1903.

Bernath, Michael T. Confederate Minds: The Struggle for Intellectual Independence in the Civil War South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Brown, Joshua. Beyond the Lines: Pictorial Reporting, Everyday Life, and the Crisis of Gilded Age America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

Bryant, Mark. Wars of Empire in Cartoons. London: Grub Street, 2008.

Dagnes, Alison. A Conservative Walks into a Bar — The Politics of Political Humor. New York: PalgraveMacmillan, 2012.

Ellegård, Alvar. "The Readership of the Periodical Press in Mid-Victorian Britain: II. Directory." Victorian Periodicals Newsletter. 4/(3 [13] September 1971): 3-22.

Lauterbach, Edward Stewart. "Fun and its Contributors: The Literary History of a Victorian Humor Magazine." Unpublished PhD thesis, 1961. Urbana: University of Illinois.

Lewin, J. G. and P. J. Huff. Lines of Contention: Political Cartoons of the Civil War. New York: HarperCollins and the S1nithsonian Institution, 2007.

Linneman. William R. "Southern Punch: A Draught of Confederate Wit." Southern Folklore Quarterly. 26/2 (June 1962): 131-136.

Miller, Henry J. "John Leech and the Shaping of the Victorian Cartoon: The Context of Respectability." Victorian Periodicals Review. 42/3 (Fall 2009): 267-291.

Morris, Frankie. Artist of Wonderland: the Life, Political Cartoons, and Illustrations of Tenniel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2005/

Mott, Frank L. A History of American Magazines, 1865-1885. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970 [first published, 1938].

Scully, Richard. British Images of Germany: Admiration, Antagonism and Ambivalence, 1860-1914. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

_____. "Sex, Art and the Victorian Cartoonist: Matthew Somerville Morgan in Victorian Britain and America." International Journal of Comic Art. 13/1 (Spring 2011): 291-325.

Silver, Henry. Unpublished diary [relating to the weekly Punch editorial dinner], 1858-1870. British Library, ADD MS 88937/2/19/1.

Sloane, David E. E., ed. American Humor Magazines and Comic Periodicals. New York: Greenwood Press, 1987.

Created 13 August 2019