Excerpts from David Cesarani's Disraeli: The Novel Politician, a review of which can be read here on the Victorian Web. — added, with introductory and explanatory comments, by Jacqueline Banerjee

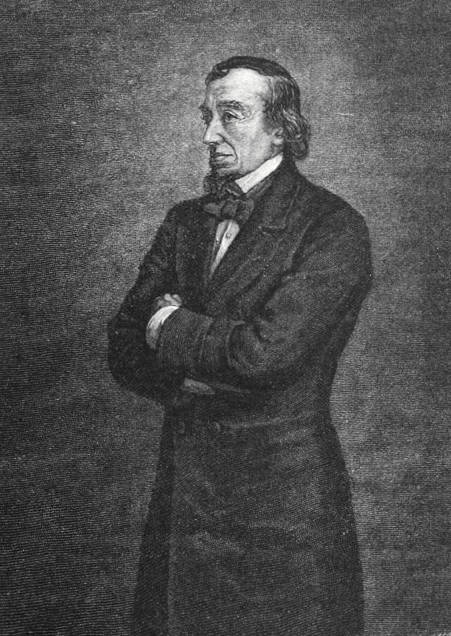

David Cesarani (1956-2015) was a noted historian whose special interest lay in Jewish history. As well as being a research professor at Royal Holloway College, London, he was director of the Holocaust Research centre, and was awarded an OBE for helping to establish a Holocaust Memorial day here. His book on Disraeli in Yale's "Jewish Lives" series explores the politician's complex relationship to his Jewishness, and takes a rather critical but not totally unsympathetic stand on his ambivalence about it. In his final chapter, he contrasts Disraeli with the German political thinker and politician Friedrich Julius Stahl (1802-1861), who also became a Christian, but converted after a true crisis of faith (not because his father had him baptised as a boy, as in Disraeli's case), and was knowledgeable about and continued to respect his Jewish heritage (rather than constructing a "mythical lineage" from it that would make him seem special). Cesarani continues, with a fine degree of insight:

Whether Disraeli needed to take comfort from his invented noble ancestry and the achievement of the Jewish prophets is open to dispute; the timing of his Jewish turn counts against such speculation. What is undeniable, however, is the persistence and sheer volume of prejudice he experienced throughout his life. Nearly every page of [Stanley] Weintraub's biography discloses an insulting reference to Disraeli pegged to his Jewish birth. Almost no one amongst Disraeli's contemporaries was immune to such expressions of prejudice. The most dramatic case is that of Edward Stanley [later Lord Derby], who started his political career as an admirer and disciple of Disraeli only to end it excoriating him for holding unEnglish beliefs. VVhen Gladstone renovated his country house at Hawarden, the new study was fitted out with false bookends, one of which was entitled "An Israelite Without Guile" by Ben Disraeli Esq.

That Disraeli was the focus of everyday, common-or-garden prejudice should not be surprising. He was a prominent public figure and a lightning rod for bigotry, just like other high—profile Jews. The Rothschilds fulfilled this function right across Europe. What is more, Disraeli positively invited attack by bruiting his Jewish origins and bragging about the ubiquity and power of "the Jews." His racialization of the Jews also incited critics to deduce that he was in his inner being a Jew, acting in concert with others of his kind: an alarming sort of crypto-Jew who had insinuated himself into the highest counsels of the nation. The result was that observers both friendly and hostile sought to explain him in terms of Jewishness. This trend was most notable and most obnoxious during the Eastern crisis of 1876-78. [233-34]

However, Cesarani finds no evidence to support those later critics who assume that Disraeli was swayed by Jewish loyalties:

Later, Jews like Cecil Roth colluded in the fantasy by tracing his mode of thought, his policies, and his conduct of foreign affairs back to his alleged Jewish sentiments. To Roth, the social legislation over which Disraeli presided between 1874 and 1830 "expressed that Jewish craving for social justice which is one of the heritage: of the Bible, and that Jewish sympathy for the underdog which is one of the results of his history." Harold Fisch detected a displaced Jewish messianism in his imperialism: Disraeli "made available to Toryism a Hebraic set of ideals and menaphors." Yet detailed studies of Tory domestic policy making and legislation reveal the absence of any consistency or idealism, let alone a Jewish dimension. The voluminous accounts of Disraeli's foreign policy, his imperialism, and the Eastern crisis likewise entirely reject the "Judaic" motives or intentions attributed to him by his critics. [234]

Not unexpectedly, then, Cesarani concludes that Disraeli was "one of the last court Jews [the socially elite bankers of the early modern period] and one of the first victims of anti-Semitism" (236). Unfortunately, that last description needs no explanation.

Related Material

- A Review of Cesarani's Disraeli: The Novel Politician by Joe Pilling

- A Review of Cesarani's Disraeli: The Novel Politician by Michel Pharand

Bibliography

Cesarani, David. Disraeli: The Novel Politician. Jewish Lives series. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2016.

Fisch, Harold. "Disraeli's Hebrew Compulsions." In Essays Presented to Chief-Rabbi Israel Brodie on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday. Ed. H. J. Zimmels et al. London: Soncino Press, 1967.

Roth, Cecil. Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield. New York: Philosophical Library, 1950.

Weintraub,Stanley. Disraeli: A Biography. New York: Dutton, 1993.

Last modified 29 December 2016