y the mid seventeenth century and increasingly as time went on Jews were becoming productive participants in the nation’s cultural life. Moses Mendes, married to a Christian, baptised, and a Freemason, wrote poems, several successful stage pieces, the libretti of a number of ballad operas, notably Robin Hood (1750; music by Charles Burney) and perhaps also those of Handel’s English language oratorios Solomon and Susanna In the words of a contemporary, Mendes was a “Person of considerable Genius, of an agreeable Behaviour and entertaining in Conversation [with] a very pretty Turn for Poetry” ( OED ). Hannah Norsa, daughter of an Italian Jew from Mantua who kept The Punch-Bowl tavern in Drury Lane, made the fortunes of the newly opened Theatre Royal in Covent Garden with an outstanding 1732 performance as Polly Peachum in John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera.

As if in anticipated contradiction of Wagner’s later reprise, in attacking Mendelssohn and Meyerbeer, of an old saw — picked up by Shakespeare in Lorenzo’s comments on Shylock — about Jews’ having a suspicious attitude and thus no intimate relation to music, Jews in late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century England were particularly drawn to music, which became one of the most successful areas of their acculturation. By the last quarter of the eighteenth century the Abrams sisters— the sopranos Harriet and Eliza and the contralto Theodosia — were appearing regularly on the London stage or in concert halls. Harriet, celebrated for her performances in works by Handel, had the lead role, at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, in Mayday, or The Little Gipsy (1775), written especially for her by David Garrick – the last of more than twenty plays by the celebrated actor and theatre director – with music by her teacher, the prolific composer Thomas Arne. She also gave annual benefit concerts in 1792, 1794 and 1795, in which she was accompanied by Joseph Haydn on the piano. In addition, Harriet Abrams composed several songs, two of which, "The Orphan's Prayer" and "Crazy Jane", became very popular. She also published collections of Italian and English canzonets, Scottish songs harmonised for two and three voices, and sentimental ballads. A collection of ballads that she put out in 1803 was dedicated to Queen Charlotte.

John Braham

John Braham by Samuel De Wilde, 1819. Watercolor. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

John Braham — originally, no doubt, Abraham, Abrahams, or Abram (Conway, “John Braham,” 31; Sands, 203-04) — a former meshorrer (choirboy assistant) to the chazzan (cantor) Myer Leon at London’s Great Synagogue, became one of the most celebrated tenors of the early nineteenth century. While he was being trained — first as a boy singer by his older colleague at the synagogue, who, also sang regularly at Covent Garden under the name Michaele Leoni; then, later, after his voice broke, by the highly regarded Italian countertenor Venanzio Rauzzino (to whom Mozart had offered the lead role in Lucio Silla in Milan in 1772 and for whom he composed the motet Exultate jubilate) in the fashionable resort town of Bath — the young Braham enjoyed the practical support of the wealthy Jewish Goldsmid family. In return, he sometimes sang for them, along with their neighbour and occasional guest, Admiral Nelson. (Later, on Nelson’s death, he was to compose his greatest song-writing success, “The Death of Nelson,” first performed in 1811, to overwhelming applause, in an opera of his own, The Americans, at the Lyceum in London.) In 1794-95 Rauzzino arranged for his student to sing at the Assembly Rooms in Bath, where he was warmly received, and by November 1796 Braham had made his debut, to great acclaim, in Grétry’s Zemire et Azor, at the Italian Opera in London, an extraordinary achievement for a singer born and trained in England, let alone an English Jew. His first appearance at Covent Garden took place the following year and with it the long triumphant phase of his career was launched. Braham performed before enthusiastic audiences in every major continental house – in Paris (before Napoleon’s first wife Joséphine de Beauharnais) and in Florence in 1798, at La Scala in Milan in 1798-99, in Livorno (before Nelson) in 1800, in Venice, Trieste, and Vienna in 1800-1801 — as well as in Britain (in Mozart’s Tito and Così fan tutte, for instance, at the Italian Opera in 1806-16). In the mid-1820s he sang Max in the first English production of Weber’s Der Freischütz with such success that Weber was invited to compose an opera for him to be sung in English and performed in England. The result was Oberon, with the ailing Weber coming over to England to conduct the rehearsals himself. Braham was given the leading role of Huon de Bordeaux, and Weber, having composed two fresh arias to suit the celebrated tenor, conducted the first twelve performances himself, starting on 12 April 1826. In June of that year, at Weber’s funeral, Braham sang in Mozart’s Requiem (Conway, Jewry, 86; Sands, 217).

Braham thus became the first English-born male singer to command a European reputation. Partly by his own choice — he regularly supported Jewish charities and causes until his marriage to a Gentile woman in 1816 — and partly because his audiences in England never let it out of their minds, his Jewishness remained a prominent feature of his persona, to the point that the nation’s leading, internationally renowned tenor was at the same time an important incarnation of “the Jew” in the British consciousness. Not surprisingly, therefore, his being Jewish could be the object of snide remarks, even by those, like Charles Lamb, who admired his art (Conway, 84-85). This was by no means always the case, however. Thus the eminent man of letters, Henry Crabb Robinson, a former barrister, journalist (foreign correspondent of The Times from 1807 to 1809), and friend of Blake, Coleridge, Lamb, and Wordsworths, wrote on March 30, 1811 of his performance in The Siege of Belgrade, a comic opera put together with music by Mozart and Salieri among others, at the Lyceum Theatre:

His trills, shakes and quavers are, like those of all the other great singers, tiresome to me; but his pure melody, the simple song clearly articulated, is equal to anything I ever heard. His song was acted as well as sung delightfully; I think Braham a fine actor while singing; he throws his soul into his throat, but his whole frame is animated, and his gestures and looks are equally impassioned.

“He is incomparably the most delightful male singer I ever heard,” Robinson added four days later (Robinson, 1:325, 327).

The absence of any hint of anti-Judaism in Robinson’s comment may not be an accident. Robinson was an early Unitarian and one of the founders of London University, which was set up in 1826 in response to the continued exclusion of Catholics, Dissenters, and Jews from Oxford and Cambridge.

Isaac Nathan

Isaac Nathan, a composer of light-weight dances and songs, was yet another English Jew who achieved some celebrity or notoriety in the musical world of the early nineteenth century. Born in Canterbury, the son of a Polish-born chazzan or cantor and his English Jewish wife, Nathan was and still is best known for having persuaded George Gordon, Lord Byron, to write his Hebrew Melodies to music composed by Nathan. For the most part, Nathan adapted melodies from the synagogue service. Few, if any, of these were in fact handed down from the ancient service of the Temple in Jerusalem, as Nathan claimed. Most were European folk-tunes that had become absorbed into the synagogue service over the centuries. They were, however, the first attempt to present the traditional music of the synagogue, with which Nathan was obviously well acquainted through his upbringing, to the general public. The success of Byron’s Hebrew Melodies made Nathan relatively well known. He claims to have been appointed singing teacher to Princess Charlotte, the Princess Royal, and music librarian to the Prince Regent, later George IV. His edition of the Hebrew Melodies was indeed dedicated to the Princess Royal, presumably by royal permission (Conway, Jewry, 86; Ph.D. thesis, 121-34). As for Nathan’s relation to Byron, their friendship endured, with some condescension on Byron’s part, until the poet’s departure from England, on which occasion Byron, who had already granted his collaborator the copyright to the Hebrew Melodies, gave Nathan a £50 note and Nathan reciprocated with a gift of matzos, described as “passover cakes.” A friendly exchange of letters accompanied the exchange of gifts.

John Barnett

John Barnett by

Charles Baugniet. Oil on canvas, circa 1839.

Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Considerable success as a composer was also achieved by one John Barnett, the son of an Ashkenazi jeweller who had changed his name from Bernhard Beer on settling in England. Born at Bedford in 1802, Barnett sang on the stage of the Lyceum Theatre in London at the age of eleven. His good voice led to his being given a sound musical education so that, after his voice broke, he began composing songs and lighter pieces for the stage. A collection of Lyrical Illustrations of the Modern Poets appeared in 1834. An opera, The Mountain Sylph, received a warm welcome when produced at the former Lyceum theatre, newly reopened and renamed “The English Opera House,” on 25 August 1834, and was given over 100 performances — an unusual success at the time. It was followed by Fair Rosamond, to a libretto by his brother, in 1837, Farinelli in 1839, both at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and many others, none as successful, however, as the first. Even after his career as an opera composer declined and he retired to the country, he remained musically active as a singing-master in Cheltenham. Systems and Singing-masters was published in 1842, School for the Voice two years later. Barnett also wrote several songs for the theatre in collaboration with the comic actor, playwright and theatre manager John Baldwin Buckstone, as well as some instrumental works, including three string quartets and a violin sonata.

The writer Grace Aguilar had a younger brother, who won recognition as a pianist, composer, and music teacher. Born in England to well educated Portuguese-Jewish parents in 1824, Emanuel Abraham Aguilar (1824-1904) studied music in Frankfurt, where he was the first to perform Chopin’s F minor concerto and where many of his own compositions were also performed, before returning to England and settling in London. He composed two operas – Wave King (1855) and Bridal Wreath (1863) as well as overtures, symphonies, cantatas (including, in 1888, in collaboration with the author, a musical setting of Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market), chamber music, and songs. He also produced piano transcriptions of music by J. S. Bach. According to James D. Brown and Stephen S. Stratton, authors of a British Musical Biography (1897) “his piano recitals have been for many years, a regular feature of the London musical season.

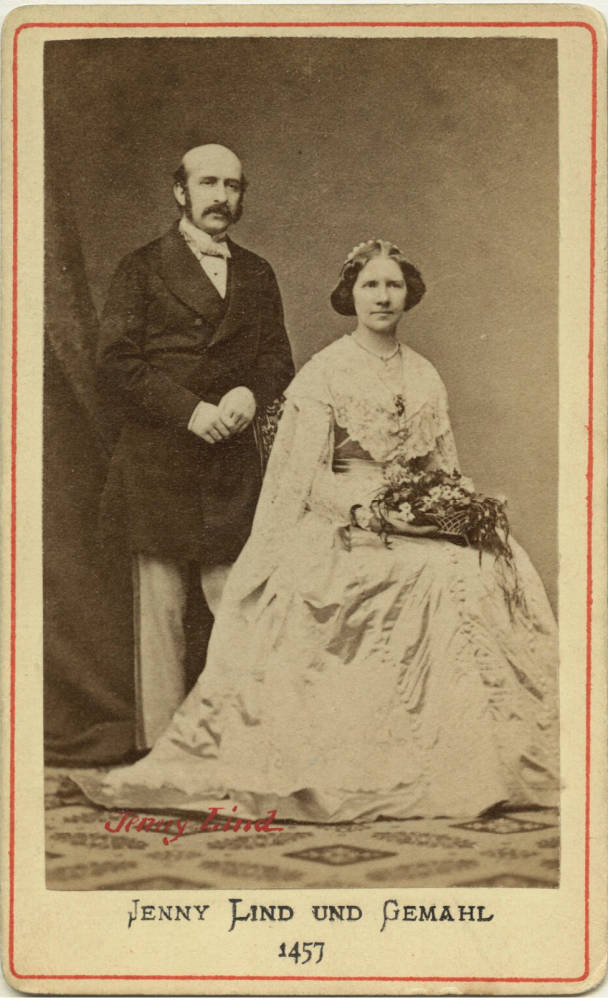

Carte de visites of Otto Moritz David Goldschmidt & Jenny Lind by Henry Murray (left) and Emilie Bieber (right). Both courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

How not to conclude this short review of Jews in the English musical world of the late eighteenth century and the earlier decades of the nineteenth without mentioning Jenny Lind, the legendary “Swedish Nightingale”? With her Jewish composer husband Otto Goldschmidt, a former student of Felix Mendelssohn, Lind, who had begun to sign herself Jenny Lind-Goldschmidt, settled in England in 1856, just two years before Lionel de Rothschild’s winning permission to take his seat in Parliament ended all restrictions on the Jews of England. In 1863 Goldschmidt, who had become a naturalised British citizen, was appointed Vice-Principal of the Royal Academy of Music and in 1883 Lind-Goldschmidt became the Academy’s first Professor of Singing.

Related material

Bibliography

Conway, David. “John Braham: from meshorrer to tenor.” Jewish Historical Studies, 41 (2007): 37-61.

Conway, David. “Jewry in Music,” Jewish Entry to the Musical Professions 1780-1850. Ph.D. thesis, University College, London, 2007 (https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1444147/1/U591449.pdf Accessed 25.6.2020.

Conway, David. Jewry in Music: Entry to the Profession from the Enlightenment to Richard Wagner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2012.

Robinson, Henry Crabb. Diary, Reminiscences, and Correspondence, ed. Thomas Sadler, 3 vols. London: Macmillan and Co., 1869.

Sands, Mollie. “John Braham, Singer.” Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England, 20 (1964): 203-01.

Last modified 20 July 2020