Throughout his tour of the British North American Colonies in 1860, Dr. Henry Wentworth Acland, Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford University and physician to the Prince of Wales, followed his professional interests in medicine and science, and recorded his impressions in twelve illustrated letters to his wife, Sarah. His tour included visits to asylums for the mentally ill in the four Atlantic colonies and in Quebec.

We are most grateful to be able to reproduce here material from Jane Rupert's edition of Acland's Letters of a Distinguished Physician from the Royal Tour of the British North American Colonies, 1860. The whole edition may be viewed on the web by clicking here.

hen the St. John's [Newfoundland] asylum opened in 1854, patients were treated in accordance with the revolutionary theory of moral therapy, the traitement moral advocated during the 1790s particularly by Philippe Pinel, a French physician. Influenced by the idea of morality expressed, for example, in Adam Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), the goodness of the practitioner and his sympathy with those suffering were considered essential to treatment according to the precepts of moral therapy, along with a knowledge of each patient's illness. In an exposition that embraced the theory of moral therapy, Acland wrote a gold-medal winning essay for a course on medical jurisprudence at the University of Edinburgh in which he provided a taxonomy of mental diseases with observations on the possibility of their treatment. Categories of mental illnesses described by Acland included various kinds of melancholia, perceived as a disturbance of the will, the affections, and the understanding; monomanias like suicidal mania, kleptomania, and puerperal (postpartum) mania; dementia, a loss of the perceptive and intellectual faculties; and diseases of the imagination or memory.

Moral therapy included the re-direction of the patient's attention through recreation provided by books and music and through manual occupations such as tailoring, baking, and farming.

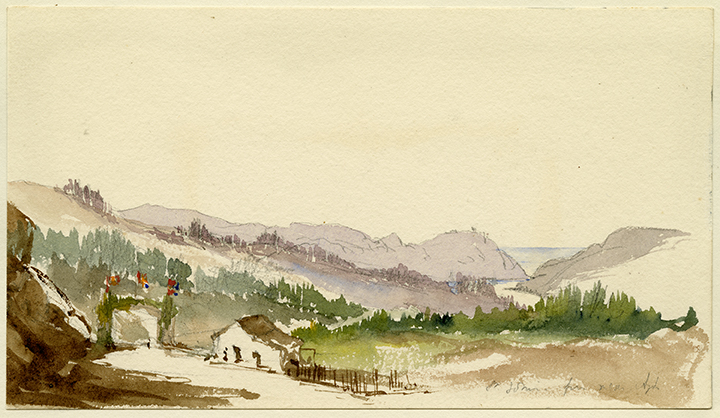

"Looking back on the Harbour of St. John's from near the Asylum, July 25, 1860." In the distance are the steep rock walls at the harbour's entrance and in the foreground an arch decorated with evergreens in honour of the Prince of Wales.

After his arrival at St John’s in 1837 as a recent graduate from the University of Edinburgh, Dr Henry Hunt Stabb campaigned tirelessly for a government-supported mental asylum in order to remove “lunatics” from their appalling confinement in places like the Riverdale Hospital where they were often attached to chains in basement cells and sick wards.

In establishing and administering the asylum, Dr Stabb had worked in conjunction with Dorothea Lynde Dix, an American crusader whom Acland later met at a breakfast in Chicago. Since the 1840s, Miss Dix had campaigned successfully for the establishment of well-heated, airy, brick asylums with tall windows and views of open spaces and rivers. After the disastrous fire that swept St John’s in 1846, leaving 12,000 out of 19,000 homeless, both the asylum and hospital were prudently equipped with ready water supplies to extinguish fires.

In Prince Edward Island, at another asylum, Dr. John Mackieson deplored the asylum's physical condition and its lack of funds even for adequate heating or an exercise yard. He was not an adherent of moral therapy but a medical materialist subscribing to the theory that insanity was a material or organic condition of the brain which required the chemical treatment of drug therapy. Believing that the best remedy was the removal of patients to one of the new colonial asylums, Acland spoke on this matter to George Dundas, lieutenant governor of Prince Edward Island, to Lord Mulgrave, lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia, and to Judge James Peters, son-in-law of the Nova Scotia shipping magnate, Samuel Cunard. In 1876 the Prince Edward Island legislature approved the construction costs for a new building and the new asylum was opened in 1880.

In his "Notes on the Medical Arrangements of the Four outer Colonies," placed at the end of the twelve letters, Acland wrote: In Prince Edward's island is a Poor House & Asylum conjoined. The Medical Officer is now resident — his salary is £40 a year — the Master is an old Sergeant. In his relations to the Inmates I saw no symptom of roughness or dislike. But the place is filthy and ill kept. The Chronic cases except those of mere imbecility were locked up in single cells. One had a long heavy chain to one ancle [sic]. Several are down in a damp cellar in separate cells. The ground seemed to be within three feet of the ceiling, a small barred window admitted light & air. So repulsive a spectacle I scarce ever saw — indeed I may say except a chained Maniac at Constantinople never. The Poor's [poor house] part of the institution was not satisfactory — It smelt offensively and was very dirty — Each Inmate Lunatic costs about £21.5.0 (currency) £16.0.0 sterling — The sole remedy for this state of things would appear to be at present union with one of the other islands & transfer of cases at a given rate, unless the Colony can afford an Asylum. I now understand Miss Dix's horror. I have represented the matter to Judge Peters, Lord Mulgrave, and Governor Douglas [Dundas].

Links to Related Material

- Dr. Henry Wentworth Acland (1815-1900)

- Acland's Visit to the Toronto Observatory

- Victorian Hospitals

- Victorian Psychology

- Acland, Ruskin, and the Pre-Raphaelites

Bibliography

Acland, Henry Wentworth. "Notes on the Medical Arrangements of the Four outer Colonies of N. America 1860 and on the Poor Law System" and "Letter 2: Newfoundland, St John's" in Letters of a Distinguished Physician from the Royal Tour of the British North American Colonies, 1860. ed. Jane Rupert, web: janerupert.ca

---. Feigned Insanity, How Most Usually Simulated and How Best Detected. London: R. Clay, 1844.

Baker, Melvin. "Insanity and Politics: The Establishment of a Lunatic Asylum in St John's Newfoundland, 1836-1855." Newfoundland Quarterly 77, no. 2 & 3 (1981): 27-31.

Shephard, David A.E. Island Doctor: John Mackieson and Medicine in Nineteenth-Century Prince Edward Island. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2003.

Created 24 July 2023