This article has been peer-reviewed under the direction of Professors Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge (University of Victoria). It forms part of the Great Expectations Pregnancy Project, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. [Click on all the images to enlarge them.]

In 1841, following the birth of her second child, Edward, Prince of Wales, Queen Victoria described a "lowness" that "made me quite miserable" (Raymond 73-4). In so doing, she shared the experiences of many women suffering depression, or in some cases more extreme manifestations of mental breakdown, following their deliveries. These forms of mental disturbance increasingly attracted the attention of physicians during the early nineteenth century, dovetailing with the expansion of obstetrics and psychiatry as discrete medical specialities. The mental disorder that came to be labelled puerperal insanity (puerperal refers to the period of about six weeks after childbirth) would challenge Victorian notions of domesticity and femininity as women flouted ideas of maternal conduct and feeling; turned against their newborn children as well as their husbands and families; neglected their appearance and household duties; displayed rude, violent, and unruly behaviour; or fell into deep and despairing melancholia.

Labelling and Framing Puerperal Insanity

Though the diagnosis of puerperal insanity has been closely associated with the work of a French psychiatrist, Louis-Victor Marcé, who wrote an extensive treatise on the subject in 1858, by the late eighteenth century, physicians were describing women's vulnerability to mental disorders related to pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding. In 1798, Dr. John Haslem commented on the large numbers of patients admitted during the puerperal period to Bethlem Hospital (an institution for the mentally ill based in London), where he served as apothecary, and in 1801 the renowned obstetrician Thomas Denman included a substantial section on mania in pregnancy among new mothers in his midwifery textbook.

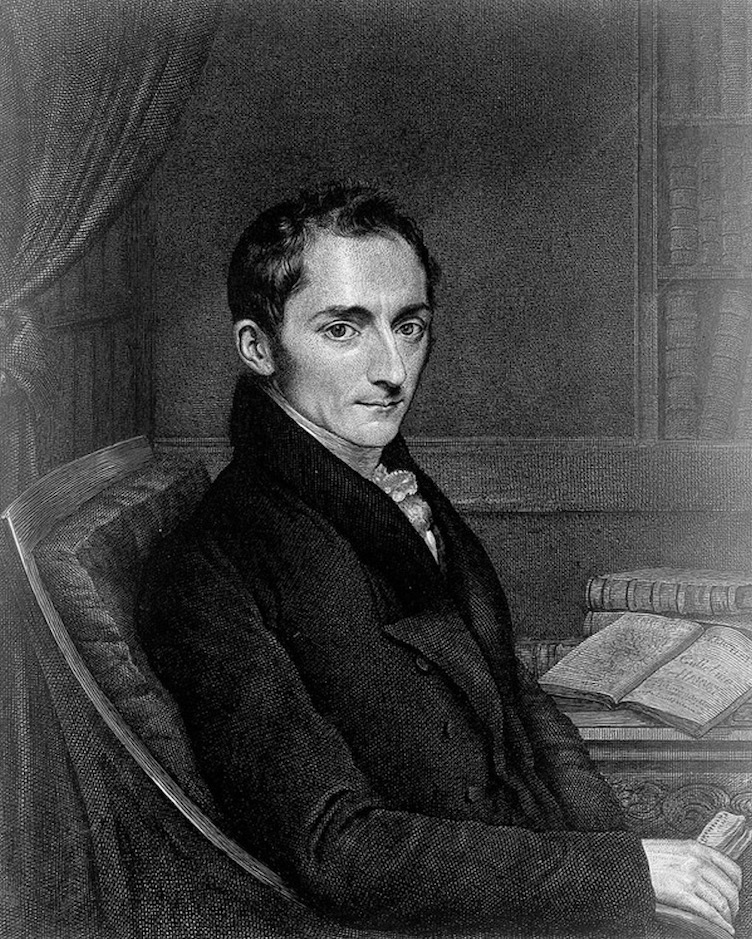

Robert Gooch, line engraving, by J. Linnell, 1831. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

However, it was the work of obstetrician Robert Gooch that was particularly significant in framing the disorder that became widely known as puerperal insanity. Published in 1820, his brief but influential treatise, Observations on Puerperal Insanity, included descriptions of cases that he had encountered in his private practice, explaining how a disorder that at the outset excited little apprehension was converted into wild and incoherent mania or the bewilderment, confusion, and depression that marked the melancholic form. Tethering the disease firmly to childbearing — which he described as a dangerous passage to be traversed, starting with conception and ending only when the child was weaned — Gooch explained:

During that long process … in which the sexual organs of the human female are employed in forming; lodging; expelling, and lastly feeding the offspring, there is no time at which the mind may not become disordered; but there are two periods at which this is chiefly liable to occur, the one soon after delivery, when the body is sustaining the effects of labour, the other several months afterwards, when the body is sustaining the effects of nursing. [On Some of the Most Important Diseases, 54]

The term puerperal insanity was rapidly adopted by obstetricians and those in the emerging field of medical psychology or psychiatry. Gooch's account was written at a time when there was increased interest in disorders related to reproduction and the diseases of women, and when obstetricians and man-midwives were framing childbirth as ever more risky, requiring the attendance of a trained physician, who had attended courses in midwifery, rather than a female midwife, who might have undertaken an apprenticeship with an experienced midwife but lacked any "formal training." By the 1830s, there was broad agreement that puerperal insanity — alongside the sister disorders of insanity of pregnancy and lactational insanity — was prevalent and a major risk of childbirth. Though puerperal mania was described as more shocking (involving violent displays, disgusting language, and delusions), melancholia, insidious and stealthy, was troubling for its tendency to take hold of women, causing them to lapse into permanent insanity. As large public asylums were set up during the mid-nineteenth century, cases of puerperal insanity began to account for high numbers of female admissions. By the mid-nineteenth century, both Warwick and Hanwell Asylums reported that cases of puerperal insanity made up 11 per cent of female admissions, and, at Bethlem, rates of 12 per cent were recorded (Marland, Dangerous Motherhood, 8). Similar figures were reported in the United States, where puerperal insanity was generally considered responsible for at least 10 per cent of female asylum admissions (Theriot, "Diagnosing Motherhood," 405).

"The Hospital of Bethlem, St George's Fields, Lambeth, 1816." Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

It was not only the numbers of women seen as vulnerable to developing severe mental illness around childbirth that shocked contemporaries. The symptoms also upturned ideas of female grace and respectability as well as those of maternal feelings and duties. Janet Smith, who was admitted to the Royal Edinburgh Asylum in April 1853, was noted to be naturally "of a cheerful and frank disposition and of temperate, active and quiet habits." Yet, on admission, the asylum case book described her as "noisy & obstinate & destructive of clothing." After six weeks in the asylum, she was even worse: "exceedingly mischievous, very destructive, and dirty, she used the most profane and obscene language … abused everyone who came near her, spat in their faces … and did every sort of mischief" ("Janet Smith," 411). Though he expressed it in a more restrained language, obstetrician James Reid explained in 1848 that the cases he met in his private practice were typified by anger and violence, incessant talking, negligence of and aversion to the child and husband, and, "although the patient may have been remarkable previously for her correct, modest demeanour, and attention to her religious duties, most awful oaths and imprecations are uttered, and language used which astonishes her friends" (134-35).

Causes, Treatment, and Location of Puerperal Insanity

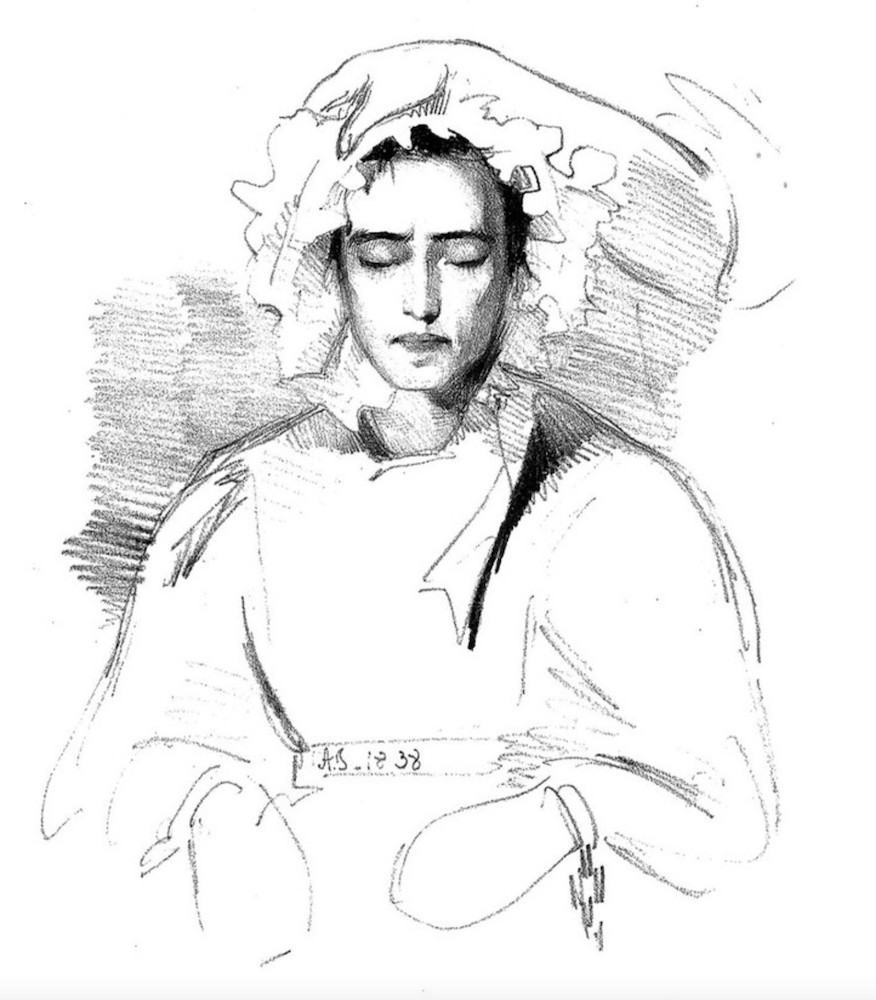

"Puerperal mania" from The Physiognomy of Mental Diseases by Sir Alexander Morison. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

While most physicians agreed that puerperal insanity was prevalent and a marked risk for all childbearing women, there was disagreement about its precise causes and what might make women particularly vulnerable to it. The well-known psychiatrist and asylum superintendent Dr. John Conolly suggested that rates were higher in France because French women continued in their usual employment around childbirth, whereas other commentators linked the disorder to higher incidences of illegitimate births ("Description" 350). While puerperal insanity arose frequently in women who had experienced a "normal" delivery, many claimed it was more common in women who had experienced a difficult birth (painful, protracted, or involving instruments) or following the delivery of twins or a stillborn child. The disorder was also attributed to either bodily or psychological changes, or both. In 1843, Dr. Alexander Morison claimed the changes "that take place in the vascular system, and the increased sensibility of women during pregnancy, childbearing and suckling, render them liable to insanity" (15). Hereditary influences were also described as significant, notably on the female side of the family, though it was particularly towards the end of the century that hereditary disposition was seen as a critical factor. Some authorities claimed that puerperal insanity was more likely to occur among first-time mothers who were physically and emotionally traumatised by the process of giving birth; others linked it to frequent childbearing and exhaustion. Women of all social classes were deemed vulnerable, though insanity of lactation was recognised as being the result of the efforts of women living in poverty to continue to breastfeed their infants when they themselves were exhausted, weak, and poorly nourished, particularly if they had delivered large numbers of children (see Marland, Dangerous Motherhood, 150-54).

Unlike many other mental disorders, however, puerperal insanity was seen as being largely curable, even if it might take many months — around 7 months was regarded as typical — for patients to recover. Separation of the infant from the mother was recommended by medical practitioners, not least because she might neglect or turn against the child, but also because the presence of the infant was seen as likely to impede recovery. Treatment was likely to be mild, with little medical intervention, based on regular purging, tonics, and nutritious diet; careful observation and nursing; and rest, though after the 1860s sedatives were increasingly prescribed. Some doctors might also use opiates to encourage sleep, but others derided them, claiming that they made patients more excitable as well as causing constipation. As to the place of cure, and who should take responsibility for managing cases of puerperal insanity, there was considerable division along professional lines. Obstetricians were keen to continue to supervise such cases and, particularly in the case of well-to-do patients who could afford private attendance and nursing care, to keep patients at home or to remove them to a private residence for treatment. Asylum doctors, meanwhile, stressed that early removal to an asylum greatly boosted the woman's chances of recovery. Dealing largely with poor women, the medical superintendents of large public asylums became familiar with the impact of poverty on women who were admitted in poor physical as well as mental health. Many of these women also experienced unhappy domestic circumstances, overwork, and abusive husbands, and some had been deserted by the father of the child. In Hanwell Asylum in 1871, 263 women (over 63 per cent of cases of puerperal insanity) were unmarried (Marland, Dangerous Motherhood, 155). In 1869, the medical superintendent to Warwick Asylum, Dr. Henry Parsey, referred to three infants born in the asylum that year whose mothers were admitted during their pregnancies. One was single, and "the sense of disgrace attaching to her condition seems to have been the exciting cause of her insanity" ("Annual Report," 11).

The Case of Sara Coleridge

We know little about how sufferers reflected on their own experiences or tried to explain why they had fallen ill, making us largely reliant on doctors' accounts of the illness and occasional comments by family members or the women themselves. This lack of women's voices makes the example of Sara Coleridge's depression following the birth of her second child, Edith, in 1832 particularly compelling and valuable for historians. Sara, the daughter of poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, noted details of her debilitated and nervous state in a diary initially intended to record her children's growth and development. Though her condition was never explicitly labelled "puerperal insanity" by Sara, her mother attributed her "very sad state of stomach & nerves" to "over-nursing"; "her disease, which, by the Medical-man is called Puerperal is of the most distressing kind" (Minnow 169-70). The deepening of Sara's mental anxiety and her feelings of nervous derangement persuaded her that it was time to wean Edith, even though she was just two months old, and the diary takes on a particularly disturbing tone in the early autumn of 1832, recording the struggle to get Edith to suck from a bottle, Sara's sore breasts, and Edith's bowel upsets and sickliness, all while Sara was desperately depressed. By September, Sara felt herself increasingly debilitated, "weak and miserably nervous and fluttered." She noted in her diary that she was "going on very sadly … nervous derangement is my complaint. Stomach and bowels out of order — great weakness — nervousness — shiverings and glowings" (12 September and 20 September 1832). Sara had trouble sleeping and took opiates regularly to induce sleep.

Sara's descriptions of her condition evolved into a gruelling narrative of depression and confusion, as the illness blurred with the effects of the narcotic drugs with which it was treated and to which Sara clung. Yet she also negotiated her way through her illness in a way that gave her the freedom to work on literary projects and to absent herself from the household and childcare, as these tasks were increasingly allocated to her mother and the children's nurse. Sara appears to have been familiar with current medical knowledge and was particular in her choice of physicians. Those who recommended reducing her intake of opiates were quickly let go. In contrast, after being taken from her home in Highgate in London to the seaside resort of Brighton in the autumn of 1832, Sara wrote of her optimism in finding herself in safe hands with a local doctor, Mr. Lawrence, who appeared to be "very clever & very attentive & perfectly understands my case, having attended, as he says similar persons in the same state his own wife among the rest. He has no doubt of setting me right sooner or later — he says cure may be sudden or it may be tedious, but that he never knew a case like mine which did not turn out well in the end" ("Sara Coleridge to Mary Pridham Coleridge"). Nancy Theriot has also described women's agency in negotiating their mental illness with their physicians in late nineteenth-century America, arguing that women themselves contributed to the creation of disease categories such as puerperal insanity ("Women's Voices").

Puerperal Insanity and Infanticide

Among the most shocking symptoms of puerperal insanity related to women's indifference, neglect, or hostility towards their children. These attitudes were considered defining characteristics of the disorder, and physicians recommended not leaving women suspected of suffering puerperal insanity alone with their infants. Aversion to the infant found its most extreme and disturbing manifestation in cases of infanticide. During the nineteenth century, the plea of temporary insanity was drawn on increasingly in the courtroom, as doctors serving as expert witnesses attributed mothers' violent acts against their infants to puerperal insanity. Oftentimes, these cases involved single women, most usually servants, giving birth alone and then killing the child in a state of desperation and frenzy, but many married women described as previously respectable and good mothers appeared in nineteenth-century courtrooms accused of infanticide. One much-reported trial took place at the Essex Lent Assizes in 1848, when Mary Prior, a 37-year-old married woman, was accused of the murder of her infant, whom she almost decapitated with a razor. Her surgeon, Thomas Bell, declared Prior to be labouring under puerperal mania. The neighbours, too, often key witnesses in such cases, "thought her mind was not as it should be" ("Chelmsford"). Mary Prior was acquitted on the grounds of puerperal insanity, and women facing charges of infanticide were frequently treated with sympathy, their terrible crimes blamed on temporary derangement. Many were acquitted. Others were sentenced to prison, removed to a local asylum for treatment or to Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum. Infanticidal women accounted for most of Broadmoor's female admissions after it opened in 1863. Classified as an asylum for the "criminally insane," Broadmoor was envisaged as a place of rehabilitation and cure, though many women who had committed infanticide remained in Broadmoor for many years or died there (Pedley).

Woking Convict Invalid Prison, five women prisoners convicted of infanticide. Print after Paul Renouard, 1889. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Restoration

Though some would lapse into a permanent state of chronic depression or would suffer mental breakdown with every subsequent pregnancy or birth, the majority of women recovered from puerperal insanity. Sara Coleridge's depression persisted for many years, before finally lifting in the early 1840s, at a time when her husband was desperately ill but she herself was free from the burdens of childbearing. In the meantime, Sara had gone through three more pregnancies and several miscarriages, causing her great anguish and physical and mental prostration. Her three infants had died shortly after delivery, likely due to Sara's addiction to opiates. Janet Smith, reported to be profane, violent, and abusive as she stormed around the Edinburgh Royal Asylum, similarly experienced a "remarkable change" in September 1853, almost seven months after her admission. She began to inquire about her friends, husband, and child and became "cheerful, kind, tranquil and industrious"; one month later, she was removed from the asylum to "her husband's protection" ("Janet Smith," 411).

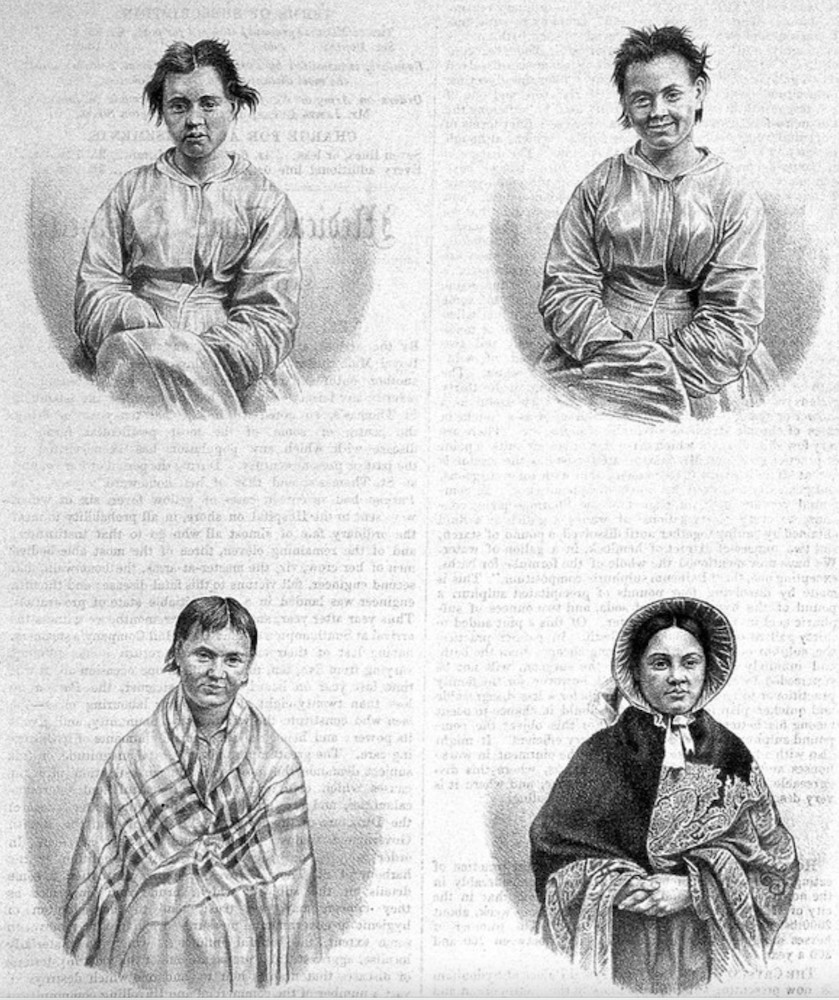

"Puerperal mania in four stages,"

Medical Times & Gazette , 1858.

Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

A series of photographs attributed to Dr. Hugh Diamond, medical superintendent of the female department of the Surrey Asylum and reproduced in the Medical Times & Gazette in 1858, evocatively depicted four stages of puerperal mania, from admission to discharge. The woman's subdued state on admission was followed by a stage of excitement and mirth, then relapse, and finally, as described by John Conolly in an accompanying text, the fourth portrait revealed "composed features and pleasant honest face, animated still, but no longer excited" ("The Physiognomy of Insanity," 624). Dressed up in a bonnet and paisley shawl, the recovered mother is represented as not only cured but restored to proper and appropriate female respectability.

Conclusion

The diagnosis of puerperal insanity gained widespread acceptance during the nineteenth century, coinciding with increased emphasis on the dangers of childbirth, which physicians claimed was likely to put women at risk not only of physical harm but also of mental breakdown. It coincided with the growth of obstetrics and psychiatry as specialized fields, with practitioners in both areas of medicine asserting their competence to treat puerperal insanity. As well as fascinating the medical profession, puerperal insanity captured public attention. As reports of infanticide trials illustrate, the idea that women might experience mental breakdown during pregnancy or after giving birth was widely accepted in the public arena. During an era when motherhood was depicted as women's most important role, and a time supposedly of great joy and fulfilment, puerperal insanity shook expectations of maternity, femininity, and domesticity, with women of all social classes displaying outrageous, disruptive, and violent behaviour. The role of the physician was not only to cure such women's mental disorders but also to restore them to their proper role within the household and family. Though we have few recollections by sufferers, there is evidence that women had some agency in shaping their diagnosis and achieving a break in their domestic duties, and, for poor women, admission to an asylum may have offered a period of rest and respite.

After the 1870s, however, the separate existence of puerperal insanity, a diagnostic category that had done good service since the 1820s in framing the relationship between childbirth and mental illness, began to be questioned in the medical literature. J. Thomson Dickson, physician to St. Luke's Asylum in London, argued, for example, that "there is nothing peculiar in the insanity of child-bed … and that so-called puerperal insanity is ordinary insanity, appearing at, and only slightly modified by the child-bearing circumstances" (380, Dickson's emphasis). Increasingly, the coincidence of childbearing and insanity was no longer regarded as sufficient to warrant a discrete diagnosis, and childbirth regarded merely as an associated or exciting cause. Nonetheless, the term continued to be widely used in medical textbooks and journals and asylum practice. In some asylums, the number of cases even appeared to increase, and between 1889 and 1891 over 14 per cent of women admitted to Rainhill Asylum in Liverpool were said to be suffering from puerperal insanity (Menzies 149). The prevalence of the disorder, rather than being associated with the strains of childbirth, alongside economic, social, or family stress, was linked increasingly to heredity and degeneration. This was notably so in Liverpool, a port city with a large, impoverished population, who were reputedly prone to drunkenness and vice. In Rainhill, a hereditary link was claimed in 18.7 per cent of cases of puerperal insanity and 30.4 per cent related to lactation (Menzies 161). A number of asylum superintendents continued to use the diagnoses of insanity of pregnancy, puerperal insanity, and lactational insanity into the 1920s and 1930s. Dr. Robert Jones, Superintendent of Claybury Asylum near London, declared childbirth to be a major cause of mental breakdown, and between 1896 and 1902, 259 women were admitted with diagnoses of insanity of pregnancy, confinement, or lactation (Jones 579; Marland, "Gestation"). Meanwhile, the term continued to be used in the courtroom, with judges and juries valuing Victorian doctors' clear descriptions of puerperal insanity in reaching a verdict in infanticide trials, and, as late as 1935, one psychiatrist declared that the term puerperal insanity was still enjoying a "protracted funeral" (James 1515).

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

"Annual Report of the Committee of Visitors." 1869. 1664/30, Warwick County Lunatic Asylum, Warwick County Record Office.

"Chelmsford — Friday, March 10. Charge of Murder. – Acquittal on the Ground of Puerperal Insanity." Journal of Psychological Medicine and Mental Pathology1 (1848): 478-83.

Coleridge, Sara. "Diary of her Children's Early Years." Coleridge, S. Misc. Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

_____. "Sara Coleridge to Mary Pridham Coleridge, Brighton, 25 October 1832." Coleridge, S. Misc. Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

Coleridge, Mrs S.T. Minnow Among Tritons: Mrs. S.T. Coleridge's Letters to Thomas Poole. Edited by Stephen Potter. London: Nonesuch Press, 1934.

Conolly, John. "Description and Treatment of Puerperal Insanity." Lancet 47, no. 1178 (1846): 349-54.

_____. "The Physiognomy of Insanity no. 8: Puerperal Mania." Medical Times & Gazette 16 (1858): 623-25.

Denman, Thomas. An Introduction to the Practice of Midwifery. 2nd ed. London: J. Johnson, 1801.

Dickson, J. Thompson. "A Contribution to the Study of the So-Called Puerperal Insanity." Journal of Mental Science 17 (1870): 379-90.

Digby, Anne. "Women's Biological Straitjacket." In Sexuality and Subordination: Interdisciplinary Studies of Gender in the Nineteenth Century, edited by Susan Mendes and Jane Rendal, 192-220. London and New York: Routledge, 1989.

Gooch, Robert. Observations on Puerperal Insanity. London: 1820. Extracted in Medical Transactions, sixth volume of Royal College of Physicians, 16 December 1819.

_____. On Some of the Most Important Diseases Peculiar to Women; with Other Papers. London: New Sydenham Society, 183.

James, G.W.B. "Prognosis of Puerperal Insanity." Lancet 225, no. 5835 (1935): 1515-16.

"Janet Smith or Curle, admitted 1 April 1853." Female Casebook 1851-55. LHB7/51/9, Lothan Health Board Archive, Edinburgh University Library.

Jones, Robert. "Puerperal Insanity." British Medical Journal (8 March 1902): 579-86.

Marcé, L.-V. Traité de la folie des femmes encientes, des nouvelles accouchées et des nourrices. Paris: J.B. Ballière, 1858.

Marland, Hilary. Dangerous Motherhood: Insanity and Childbirth in Victorian Britain. Houndsmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

_____. "'Gestation with nervous disturbance': Childhood and Mental Disorder in Early 20th-Century Asylums." The Last Taboo of Motherhood?. 16 January 2023. https://www.ltomhistory.org/post/gestation-with-nervous-disturbance-childbirth-and-mental-disorder-in-early-20th-century-asylums.

Menzies, W.F. "Puerperal Insanity: An Analysis of One Hundred and Forty Consecutive Cases." American Journal of Insanity 50 (1893-94): 147-85.

Morison, Alexander. The Physiognomy of Mental Diseases. 2nd ed. London: Longman and Co., and S. Highley, 1843.

Pedley, Alison. Mothers, Criminal Insanity and the Asylum in Victorian England: Cure, Redemption and Rehabilitation. London: Bloomsbury, 2023.

Raymond, John (ed). Queen Victoria's Early Letters. Revised ed. London: B.T. Batsford, 1963.

Reid, James. "On the Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment of Puerperal Insanity." Journal of Psychological Medicine and Mental Pathology 1 (1848): 128-51, 284-94.

Theriot, Nancy. "Diagnosing Unnatural Motherhood: Nineteenth-Century Physicians and 'Puerperal Insanity.'" In Women and Health in America, edited by Judith Walzer Leavitt, 2nd ed, 405-21. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1999.

_____. "Women's Voices in Nineteenth-Century Medical Discourse: A Step Toward Deconstructing Science." Signs 19 (1993): 1-31.

Created 28 February 2024