This is an edited, linked and illustrated version of a talk given by the author at the Marochetti Study Day organised by Caroline Hedengren-Dillon at Vaux-sur-Seine, France, in June 2023. We are most grateful both to the author and the organiser for allowing us to print it here. — Jacqueline Banerjee. [Click on the images to enlarge them, and often for more information about them.]

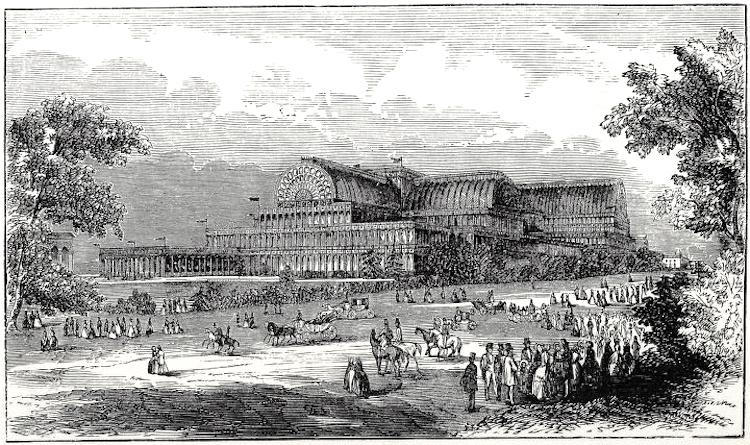

hen the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Place closed 11 October 1951, its architect, Joseph Paxton, planned to transform the Palace into a winter garden, on the model of Chatsworth’s Great Stove (inspired in turn by the Jardin d’Hiver at Versailles). Paxton’s plan was never realised. Instead, the building was used mainly for other exhibitions and concerts, until 29 April 1852, when Parliament gave the order to remove it. Therefore, the building, owned by the contractors and builders Messrs Fox and Henderson, was put up for sale.

Francis Fuller, land surveyor and estate agent, organized the purchase of the building by a group of businessmen, led by Leech and Farquhar, solicitors of the eponymous law firm. The idea of this group of investors was to create a visual encyclopedia of the arts, industrial products, botanical specimens and scientific objects, and to provide a venue for concerts and so over. In contrast to the Great Exhibition, this would encompass not only contemporary life but also the past.

Leech proposed to his co-investors to rebuild the structure in a more appropriate space, and since one of the investors was Leon Schuster, director of the Brighton Railway Company, it was decided to place the building in a location served by this line (Phillips 12). Therefore, a company was founded with the name of Crystal Palace Company, and a capital of £500,000. It was decided that the building should be re-erected in a more rural spot, so that Londoners would be attracted by the idea of spending a day in the countryside.

A piece of land of hundreds of acres was found in Sydenham, Kent. The location seemed perfect because of its proximity to the railway line, and because the building could be re-built on the hill, a position which enjoyed a beautiful view of the counties of Kent and Surrey, as well as that of the city of London (see Phillips 15-17). The contractors and previous owner, Fox and Henderson, oversaw the re-erection of the palace; Paxton was appointed Director of the Winter Garden, Park and Conservatory; while the architect/designers Owen Jones and Matthew Digby Wyatt were appointed Directors of the Fine Art Department, and were in charge of the interior decoration of the new structure.

The Crystal Palace at Sydenham from the North (frontispiece to Phillips).

The owners’ main purpose was to earn from their investment. Leech and Farquhar had promised their colleagues that the project would be extremely profitable, as testified by the profit of £186,000 earned in just five months by the Great Exhibition. The financial interest of the owners was no secret, and their evident desire for enrichment provoked criticism. Prince Albert himself argued that the enterprise was primarily motivated by the desire for fame and money, though he had to admit that the project of creating a visual encyclopedia could benefit the people. Moreover, while the main goal of the owners and many members of the company was to enrich themselves, there were other personalities involved, such as Paxton and Jones, who really believed that the project was important for entertainimg and educating the public (see Piggott 39-41).

The model for the new building was obviously the Crystal Palace of Hyde Park, but since that was created to house a temporary exhibition, modifications were necessary for the permanent building at Sydenham. The materials used were the same in both buildings, a combination of iron and glass, while the main interventions concerned the dimensions of the building: the central transept was conceived to be much higher, while the north and south transepts and two lateral towers were added (see Phillips 24-25). The first column of the building was raised by Samuel Laing (1811-1897), chairman of the Company, on the 5 August 1852, and immediately after its inauguration, Wyatt and Jones were sent to Europe to buy and commission plaster casts of the most important sculptures. The two artists were supported by Lord Malmesbury, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, who had kindly sent letters of introduction to the foreign countries and their ambassadors. The Crystal Palace Company had also requested British artists to donate their works for display in the palace, but the company ended up paying for their casts. However, from sixty to ninety percent of the budget was used for European casts (see Kenworthy-Browne 126).

The interiors were decorated by Jones, who had previously been in charge of the decoration of the Crystal Palace of Hyde Park. For the Great Exhibition, Jones had decided to paint the interiors of the building with primary colours, with the columns decorated with blue and yellow stripes. He had adopted the ideas in the chemist George Field’s studies on the effects of primary colours on the viewing of objects — for example, the notion that the color yellow made an object seem closer to the spectator. Nevertheless, Jones's decoration was highly criticized, and for the decoration of Sydenham he decided to accept Prince Albert’s suggestion of colouring the columns with a unique colour, red (see Piggott 13, 50).

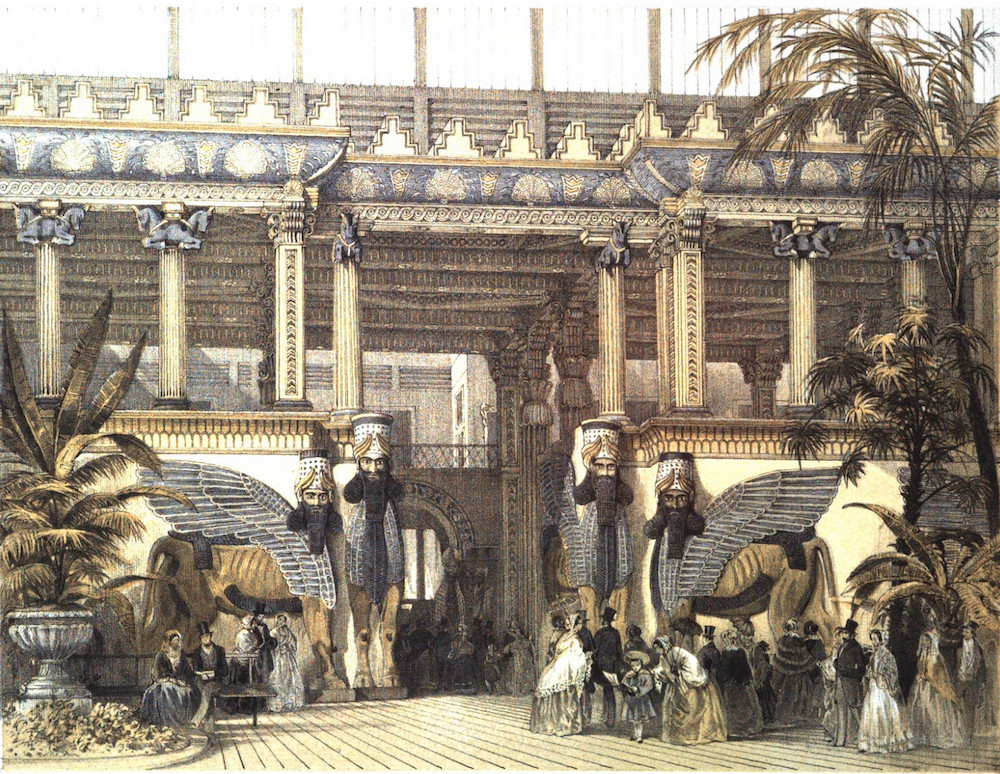

The Byzantine Court. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Not only was Jones in charge of the general decoration of the building and the fine arts courts (where he shared the task with Wyatt), but he also collaborated with Paxton in deciding the arrangement of the sculptures and plants of the transepts and the naves. Paxton in fact did not abandon his idea of a winter garden, and decided that the building, as well as the garden, should host different botanic species from all over the world. Tropical plants were positioned in one end of the building, while temperate ones were shown at the opposite end. However, Paxton found that combining plants and plaster casts was problematic: the humidity originated by plants could damage the sculptures. Therefore in 1859, having realised that plants needed moisture and plaster casts a dry condition, he had a glass screen placed between the tropical and temperate zones (Piggott 48-53).

The Egyptian Court as seen from the Nave. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

The entrance to the Crystal Palace was through the Great Transept, where most of the sculpture casts were located (Phillips 35-39). Among these was exhibited the plaster cast of Marochetti’s Sir Robert Peel. At Peel's unexpected death on 2 July 1850, numerous competitions were run for the creation of monuments celebrating the Prime Minister. As Philip Ward-Jackson has explained [in his talk on the study day], this could be considered a time of statue-mania, exceeded only after Prince Albert’s death. Marochetti had been invited to participate in different competitions for such a monument. For example, he had presented designs for Sir Robert Peel’s statue in Leeds. In addition, he had obtained the commission for Peel’s statue for the New Palace Yard in Westminster in 1851. The statue was first shown to the public in 1854, but criticised because it was considered too large for its location. (A new statue would be realized by Marochetti in 1861 and placed in Parliament Square, but in 1868 it was melted down, and a new one commissioned from Matthew Noble [see Gaunt 147-49].) Unfortunately, no documentation for the Crystal Palace commission has been found, only references to the statue in guidebooks of the period. There were probably two reasons for this commission: the popularity of Peel and the consequent "statue-mania"; and Marochetti's own pre-eminence. The absence of his works in the Crystal Palace would not have passed unnoticed, since he was one of the most successful sculptors of the time. As an example of his work, the statue of Robert Peel was no doubt chosen for its topical interest. As mentioned above, it would go on public display for the first time in 1854, the very year of the Crystal Palace’s opening.

After visiting the rest of building formed by the South Nave, which hosted the industrial courts, and the North Nave, with its fine arts court, visitors could access the garden through a glass opening at the south of the Great Transept. This conducted them to the First or Upper Terrace, which was therefore accessible from both the Great Terrace and the two lateral transepts. The spectators could admire the enormous park from it; it also provided a walk from which they could appreciate the statues, realized in different materials, with which it was decorated. The pillars that supported the terrace were decorated with, in alternation, vases designed by the Italian sculptor Raffaele Monti (1818-1881), and altogether 26 statues personifying important commercial and manufacturing countries, and the chief industrial cities of Britain and Europe. Samuel Phillips, author of the official Guide to the Crystal Palace and Park (1854), reported that the sides of the main stairs hosted the different industrial cities: on the left could be found the cities of Mulhausen and Glasgow, realized by Calder Marshall, and Liverpool, by Benjamin Edward Spence; while on the right were Paris, Lyon and Marseille, by Antoine Étex (1808-1888). The pillars of the main area were decorated on the left by the cities of Manchester by William Theed, Belfast by James Legrew (1803-1857), and Sheffield and Birmingham by John Bell; on the right with the different parts of the world: Monti’s Spain and Italy, and Bell’s California and Australia.

The stairs that led to the Lower Terrace hosted on the left: Monti’s Zollverein and Holland, and the countries of Belgium by the Belgian sculptor Guilliaume Geefs (1805-1883), the United States by the American sculptor Hiram Powers (1805-1873), and Canada and Russia by the Russian-American sculptor, Robert Eberhard Launitz (1806-1870); on the opposite side were: South America by Monti, and Greece, Turkey, China, India, and Egypt by Marochetti (Philips 152-53). Unfortunately, most of the sculptures of the Upper Terrace were lost when the Palace was burnt down in 1936 or vandalized after the abandonment of the burned palace. The ones that had survived and were in decent condition were sold in an auction in 1947, during which Marochetti’s Egypt and Étex’s Marseilles were bought by Robert Herbert-Percy, and placed in Faringdon Park (information received from Jonathan Hill, 8 June 2023). Other statues have survived until today, but their conditions are extremely precarious. In the park can be found, in addition to copies of the sphinxes from the Louvre, only one female and two male figures, and the only one that has been identified is Marochetti’s Turkey. Marochetti presented this figure as an oriental male with a long beard and a mustache, wearing a turban. He is clothed in a kaftan, with a cloak over his shoulders. In his hand he seems to hold a sword, while at his feet lies a basket. Sadly, the figure has suffered much damage, but some details of great value are visible, such as the lace edging and floral decoration of his garments.

Marochetti's Turkey, still standing at Sydenham.

As previously explained, Marochetti was also in charge of the personifications of China, Egypt, India and Greece. Some twentieth-century photos have survived, and these allow us to analyze India and Egypt. India was also provided with an oriental appearance, with a turban and long beard. Compared to Turkey, however, India wore a tunic that left his chest uncovered. Egypt was different in aspect from the two previous sculptures. It was represented as a man leaning against a sphinx, which was partially covered by the mantle that covered the upper part of his own face and back. His richly draped tunic again left his chest uncovered. Unfortunately, no photographic evidence of the appearance of Greece and China has been found.

Compared to the other sculptors involved, those who obtained a greater number of commissions were Monti, Marochetti and Bell. Probably, the reason for commissioning numerous statues from these three sculptors was due to the fact that Monti occupied the position of leading sculptor in the Crystal Palace Company. In fact, Monti was not only involved in decoration of the Upper Terrace. Some of his works were exhibited inside the Palace, and he was also in charge of the restoration of damaged casts, the decoration of the Fine Art Courts, the garden’s fountains, and numerous other decorative objects, such as the vases for the Upper Terrace. Monti and Marochetti were close friends, witness a series of letters in which, for example, Marochetti invited Monti to dinner at his house. Their friendship could be explained by the fact that both were aliens and successful sculptors, often liable to be passed over in favour of local artists. One of the letters was sent by Henry Philip [might this be Henry Wyndham Phillips, the artist who painted the The Royal Commissioners for the Exhibition of 1851?] to Monti, reporting an invitation to dinner at Marochetti’s house, where he would be able to meet a few people, among them Bell. This is the likely background for Monti's decision to involve Marochetti in the decoration of the Upper Terrace, and for Marochetti's suggesting Bell’s involvement ("Letter from Henry Philip"). The same dinner was attended by other artists, as well as Bell himself.

The Upper Terrace linked the building to the garden which hosted numerous fountains and cascades. In addition to the fountains that were completed, others were planned for the gardens, but, unfortunately, they were never realized because of the cost: on 23 January 1854, Henry Cole, who had been a member of the executive committee of the original Crystal Palace, noted in his diary: "[…] to Sydenham, with Paxton. Obliged he said to put aside all the designs for fountains too costly […]" (Henry Cole Diary). The artists in charge of the designs of the fountains were John Thomas, Bell, the French architect Hector Horreau (1801-1872), Launitz and Marochetti, while the figures for the fountains were designed by Monti. Even though this plan was never realized, at the opening of the palace, the designs were exhibited in the upper floor, in the space above the Great Transept.

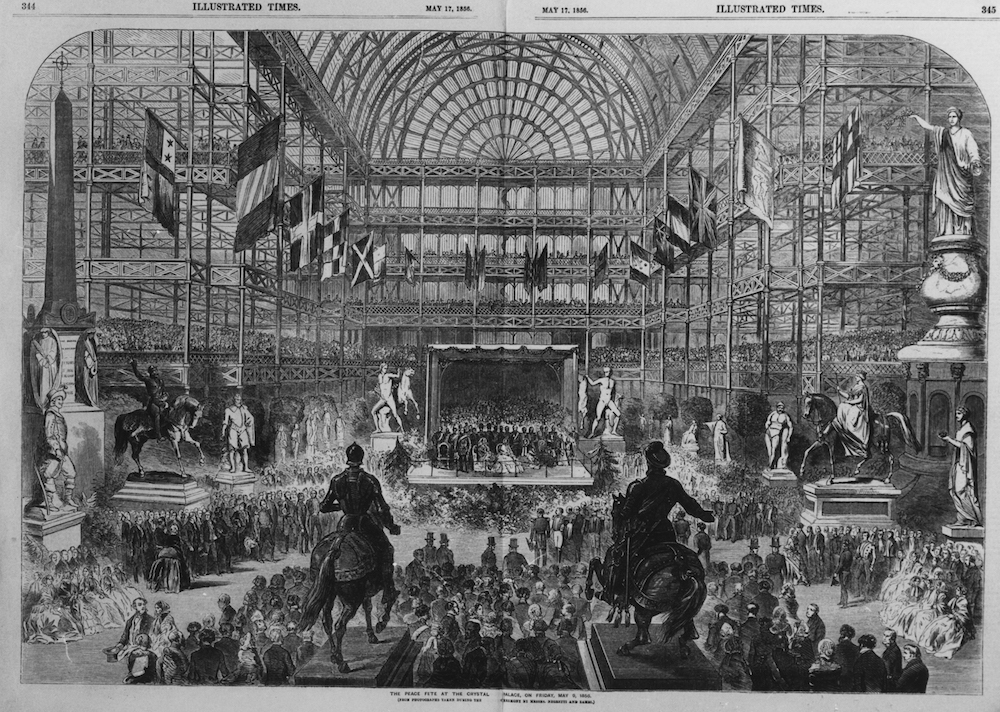

Marochetti's links to the Crystal Palace of Sydenham are not limited to his sculptures for the Upper Terrace and the designs for the fountains. On 9 May 1856 the Peace Fête was organized at the Crystal Palace of Sydenham to celebrate the end of the Crimean War, and on this occasion four monuments by Marochetti were placed as the main spectacle in the Great Transept of the building.

The Peace Fête at the Crystal Palace, on Friday, 9 May 1856, Illustrated London News, 17 May 1856: 344-45 (from the issue in volume form, kindly provided by © Philip Ward-Jackson).

The Crimean War was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and the alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, Britain and the Kingdom of Sardegna. The cause of the war was Russia’s invasion of sacred places in Turkey, and the European countries’ fear of a Russian expansion into the Mediterranean. The end of the war was signalled by the Russian defeat at Sevastopol and the Treaty of Paris. To celebrate the cessation of hostilities, and memorialise the soldiers and sailors who had fought there, the government had commissioned from Marochetti the Crimean War Memorial, also known as the Scutari Monument, because it was to be placed in the English cemetery in the Turkish city of Scutari. The monument was first shown to the British people during the Peace Fête. In addition, the Crystal Palace Company also commissioned fro Marochetti a monument known as the Peace Trophy, and decided that both monuments should be preceeded by another two casts of Marochetti’s sculptures, the equestrian monuments of Richard Coeur de Lion and of the Queen (see "Calendar of the Week," p.6).

The Peace Fête was described in detail by numerous journals of the period, and its importance was testified to by the presence of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. The Illustrated London News reported that the Great Transept had undergone many alterations for the occasion: the orchestra was moved into the north side of the transept, the floor was covered by yellow and red cloth, a gallery was built near the dais to host the Royal family, while different galleries were built on the south side of the transept for the ministers. At one o’clock every available spot near the Great Transept was taken, and during the three and a half hours that the audience waited for the Royal Family to arrive, it was entertained by music played by the bands if the Crystal Palace Company Band and the Royal Artillery. At half past three the Royal Family arrived, the Russian air was sung and finally Marochetti’s monuments were unveiled. The suspense, the music played, the parade of the officers and the presence of the Queen had roused the crowd to the point that at the monument’s unveiling the excitement could hardly be contained ("The Peace Fête").

The Scutari Monument, photographed by Müge Arseven, and kindly made available on the Creative Commons licence.

Thus, as confirmed by the different newspapers accounts, the model of the Scutari Monument was placed at the junction of the Great Transept and North Nave, preceded by the equestrian monument of Richard Coeur de Lion. The Scutari Monument was planned to be realized in granite, while the model presented at the Peace Fête was a plaster cast. It consisted of a high squared base, that was to be realized in unpolished granite, surmounted by four winged figures placed as caryatides, and a final obelisk, planned to be realized in polished granite. The four figures that decorated the monument were colossal angels of victory, represented with their wings folded, each with a crown in one hand and a palm branch in the other. The entire monument, in its shape and figures, was infused with a sense of severity and dignity, as reported by the Times: "Accordingly the angel of victory at Scutari is too proud to be sad, and too great to be proud […] the four colossal angels are to stand thus forever at the four corners of the plinth, each with folded wings, and each looking down with the self-same expression of divine content" ("Monumental Sculpture"). Even though the model of the monument was deemed a great success by the public, numerous criticisms were raised in the local press. Marochetti was accused of obtaining the commission through the help of his illustrious friends and patrons, and the monument itself was felt to be overpriced. The cost of £17,500 was considered excessive, especially since it was funded by the government (see Banerjee).

The bronze equestrian statue of Richard Coeur de Lion in Old Place Yard, Westminster (photograph by JB).

As explained above, the Crimean War Memorial was preceded by the plaster cast of the equestrian monument of Richard Coeur de Lion. The copy of this monument was probably selected to accompany the Scutari Monument because of its great success during its previous exhibition — celebrating King Richard I and his success during the crusades, it had first been shown to the public at the Great Exhibition of 1851. The colossal plaster model of the equestrian monument had been placed at the western entrance of the Palace. The monument again obtained a great success, as reported by the Evening Mail, which described Marochetti as "the same eminent sculptor whose Richard Coeur de Lion points his ponderous sword to heaven with such colossal strength and devout energy" ("Exhibition of the Royal Aacademy"). The monument was moved to the New Palace Yard in Westminster at the end of the exhibition, and was so much appreciated by the people that a petition was raised for the realization of its permanent bronze version, which was later installed in the Old Palace Yard in 1860.

On the occasion of the Peace Fête, the other monument commissioned to celebrate the end of the Crimean war, the Peace Trophy, was placed opposite the Scutari Monument, in the junction between the Great Transept and the South Nave, preceded by the copy of the equestrian monument of Queen Victoria. The Peace Trophy was an example of Marochetti’s desire to experiment by producing polychrome sculptures, even though they generated much criticism. It was a colossal female figure, standing on a vase supported by an octagonal pedestal, decorated with empty niches, and accompanied at the base by eight life-size statues, which were obviously intended to fill the niches. The monument was appreciated for its design, but it was extensively criticized for its chromatism. Marochetti had mixed different colors: the blanket on Peace’s shoulder was yellow, the colossal vase on which she was standing was red, while the eight figures were silvered, gilded and bronzed. In fact, he had used eleven different colors between the base and the pedestal. Even though his inspiration came from a classical masterpiece, the Parthenon’s Minerva (Phidia), the Crystal Palace Company later decided to remove the monument because of the continuing complaints about it in the newspapers. The monument was criticized not only because of its polychromy, but also because of the rumors spread about the amount of money spent on it by the Crystal Palace Company, to the point that the general manager, James Fergusson, was obliged to respond to the exaggerated figures by explaining that only £650 in total was spent for all four of the monuments exhibited at the Fête. He also assured the public that the cost of Marochetti's casts and their installation was covered by the sculptor himself (see Hedengren-Dillon, Part II).

As already mentioned, the Peace Trophy was preceded by the cast of the equestrian monument of Queen Victoria. The original work was commissioned in 1849 in Glasgow to commemorate the Queen’s visit to the Scottish city. Even this work was speared by negative comments, for example for the sculptor's over-emphasis on "technical virtuosity," as shown in the horse's motion (qtd. in Banerjee).

View of the the Italian terrace from the upper terrace steps today. Penge (Sydenham Hill), south-east London. Photo by JB.

Unfortunately, of all the works realized by Marochetti for the Crystal Palace, only Turkey and Egypt survived the fire of 1936. Still today the cause of that fire is unknown. It was hypothesised that it could have been caused by a cigarette or an electric spark. Whatever the cause, the Crystal Palace and its park were then abandoned; but they have not been forgotten.

Related Material

- Polychromy in the work of Baron Carlo Marochetti (1805-1867): Part II: The Peace Trophy

- Polychromy in the work of Baron Carlo Marochetti (1805-1867): Part III: Queen Victoria as "Queen of Peace,"

- Polychromy in the work of Baron Carlo Marochetti (1805-1867): Part IV: Polychromy and materials (with Conclusion and Bibliography)

Bibliography

Note: The BNA [British Newspaper Archive] was used extensively for this talk.

Banerjee, Jacqueline. "Crimean War Memorial by Baron Carlo Marochetti (1805-1867)." Victorian Web. Accessed 24 May 2023.

"Calendar of the Week," The Illustrated London News. 17 May 1856: 6.

Cole, Henry. Henry Cole Diary. 23 January 1854, NAL [National Art Library].

"Exhibition of the Royal Academy." The Evening Mail (5 May 1851): 3 (Review of the exposition of Marochetti’s Richard Coeur de Lion at the Great Exhibition of 1851).

Gaunt, Richard A. Sir Robert Peel: The Life and Legacy. London: I.B. Tauris, 2010.

Hedengren-Dillon, Caroline. Polychromy in the work of Baron Carlo Marochetti (1805-1867): Part II: The Peace Trophy. Victorian Web. Accessed 21 May 2023.

Letter from Henry Philip. AAD [Art & Design Archive, Victoria & Albert Museum], AAD/2011/3, no date.

"Monumental Sculpture by the Baron Marochetti." The Times (16 April 1856): 10.

"The Peace Fête at the Crystal Palace." The Illustrated London News. 17 May 1856): 5-6.

Phillips, Samuel. Guide to the Crystal Palace and Park. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1854.

Piggott, J. R. Palace of the People: The Crystal Palace Sydenham, 1854-1936. London: Hurst & Co., 2004.

Read, Benedict. Victorian Sculpture. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1982.

Ward-Jackson, Philip. Public Sculpture of Historic Westminster. I (Public Sculpture of Britain). Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2011.

Created 21 December 2023