Transcribed from The Art-Journal of 1894 in the HathiTrust, by Jacqueline Banerjee. The portrait and sculptures are shown in the order in which they appear there. Page numbers and given in square brackets.

T is, I believe, one of the canons of the "new" criticism — or at least the chief creed of one of its more truculent mouthpieces — that women have been tried, and found finally wanting, as original artistic exponents. This is neither the time nor place to enter into the vexed question of sex in art, but were the question at issue, it is obvious that a pretty argument for the defence might be raised by the mention of the names of adozen women who have of late gained little short of universal recognition. Amongst such a group Henrietta Montalba, no less than her famous sister Clara, holds a prominent place. In truth the sisters Montalba, like the brothers Maris, occupy, amid artistic families, something of an analogous position; analogous, I should say, to make my meaning clear, in sharin — as a family — a like bent joined to a like whole-hearted devotion.

Henrietta Montalba.

Miss Henrietta Montalba, the youngest of the four well-known sisters, was born in London, and studied, to the credit of that much-abused department, at what is informally known as "South Kensington," and later, when the family migrated to Venice, exchanging fog and stucco for the laughing waters of the green lagoons, at the Belle Arti of that city. It was, however, if I mistake not, at the former institution, that is to say at South Kensington, that a friendship sprang up between Henrietta Montalba and another sculptor, Princess Louise, who not long after invited the sisters to Ottawa during the governor-generalship of the Marquis of Lorne in Canada. Here, it may be believed, that an orgy of work was indulged in by the enthusiastic fellow-students, who, falling on each other, painted and "busted" each other with a result now known to all the world. Princess Louise’s oil-painting of Miss Montalba is still remembered by visitors to the Grosvenor Gallery, though the portrait, in which the sitter’s picturesque — and no less striking than picturesque—face is outlined against a decorative background of azalias, is now, by the Princess’s gift, a part of the Ottawa Academy collection. A probably no less well-known presentment by her sister Ellen, I may mention, was exhibited at Burlington House, and is reproduced on this page.

Handsome and accomplished, a woman of parts, Henrietta Montalba had no less the modesty which is supposed to be the prerogative of the dull and plain. A linguist, a traveller, a student, yet instinct with a rare feminine sympathy, graciousness, and tact, one is tempted to stray from the study of Miss Montalba as a sculptor in order to dwell on her delightful personality as a woman. Not but what this personality is to be seen in her work. Art is the history of personalities, or rather a man’s art is nothing but the visible record of himself. The inward and visible grace of Henrietta Montalba’s personality had, then, its proper outward and visible sign. It was visible, now in the delicate modelling of a child’s cheek, now in the suggestion of what of spirituality lay hidden in a poet’s phlegmatic face. A small terra-cotta bust of a female child called, if I remember rightly, A Study, is an excellent example of this quality of inwardness that I have in mind. There is realism in the study — more particularly in the spirited treatment of the hair; but added to the realism enough of that right kind of ideality to make the bust a type of childhood, rather than a mere portrait of some one and particular child. It may be urged, and with reason, that this inwardness must needs form an essential in the many component parts which go to make a work of art. Yet how many portraits in the plastic and other arts do we not see which give us the mere envelope or map of the subject?

Swedish Peasant. By Henrietta Montalba.

Miss Montalba’s chief essays were in portraiture, her medium being, for the most part, the somewhat treacherous and unsatisfactory one of terra-cotta. The artist worked, and worked with no little success, in Doulton’s clay, but was, as we know by her later efforts, finally weaning herself of her allegiance to terra-cotta. Two of the sculptor’s principal achievements, the head of Robert Browning, and the bust of Pallas illustrating Poe's masterpiece, “The Raven,” were in what I am forced to call the “treacherous" medium, but the portrait of the Marquis of Lorne, and the full-length nude statue known as a Boy catching a Crab, were seen translated into bronze; while a bust of Mr. George F. White was wrought in the sterner medium of marble.[215/216]

To begin at the beginning and give even the briefest notion of the scope of Henrietta Montalba’s output, we must go back to the year 1875, when the young student, then little more than a girl, exhibited a portrait of her father. The success of the attempt fortified the young sculptor for the ardours of the most wearing of all professions. Tito and Romola, companion busts in terra-cotta, and many really felicitous renderings of child life, followed. The bust of Lord Lorne, perhaps, more certainly proclaimed her powers. A glance at this portrait proves it to be informed with learning, distinction,and above all style, a quality without which a piece of sculpture is but sorry and cumbersome furniture. Happy as a likeness and as a work of art, it is no less happy in the treatment of its draperies. That bugbear of the modern sculptor, nineteenth-century dress, is tackled with skill and the uncommon sense called common. An open collar, a fur cap, and a befrogged fur-lined overcoat, an everyday winter dress in Canada, is a costume picturesque enough to satisfy the aesthetic sense without violating the probabilities; and it is in this garb that the late Governor-General of Canada is happily presented to us. Another dextrous piece of management of the drapery difficulty is to be found in the terra-cotta bust of Dr. Mezger. For here the well-known masseur of Amsterdam is depicted in a picturesque yet work-man-like blouse, out of the loose sleeves of which garment the potent, yet almost femininely delicate hands, issue with what, we feel, must needs be a characteristic gesture. In imaginative work — and it is by imaginative work that a sculptor must ultimately stand or fall — Miss Montalba’s Swedish Peasant of 1886, and her design inspired by Edgar Allan Poe's "Raven," exhibited in 1888, represent marked steps in her progress. The first essay (represented on this page) gives a spirited version of a Dalecarlian woman in the quaint dress of the Swedish province, while the more ambitious venture in the round, one, in good sooth, held to be the finest work to which the artist put her hand, is the Raven, already referred to. In the first work, spontaneity, largeness, which is yet not looseness of handling, is joined to a very individual sense of beauty, while in the second, much felicity of detail is married to a fine initial conception. Miss Montalba’s bronze Raven, to use a somewhat venerable metaphor, "lives"; in its delicately caressed modelling is to be traced the sculptor’s more than common understanding of birds.

Robert Browning. By Henrietta Montalba.

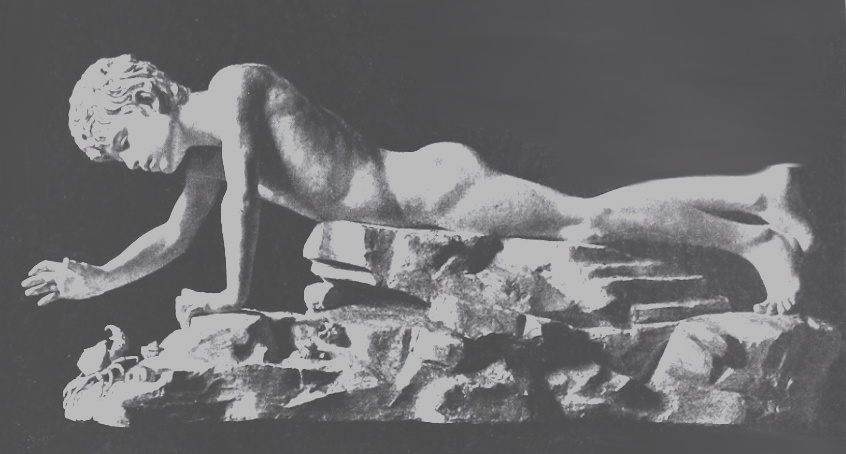

Returning to portraiture, the artist attempted another child-study in Ethel; a bust which, if suggesting something too much a Kate Greenaway in the round, has grace and decorative charm; while, happier in a more difficult sub- ject, the year 1889 saw the birth of her original, comprehensive, and vigorous version of the poet, Robert Browning. The full length statue of a Venetian fisher-boy, called a Boy catching a Crab (see illustration), was the artist's last serious essay in ideal composition, and, seen as it was a year ago in the Central Hall of the Royal Academy, needs neither comment nor praise in these pages. Briefly, what is notable in the work is its directness, its distinctiveness of conception. No over-accentuation, so common in common sculpture, no over-affectation of learning, so ordinary in ordinary sculptors, mars the modelling of the recumbent figure. The muscular structure of the torso and limbs is studied, and withal lovingly studied, but a masculine reticence, a certain rhythmical balance are marked characteristics of the work, and go a long way to make the unity as well as the naturalistic charm of the whole.

Boy Catching a Crab. By Henrietta Montalba. [Photographs of this work in the Victorian & Albert Museum]

Little remains to be said. Death has written the ugly word "Finis" at the foot of the Venetian fisher-boy, and to lift the [216/217] veil on the shadows cast by the artist’s premature death would be little short of impertinence. What can we say, in sooth, but that lives of promise, of rare appreciation and worth, prove mutable at moments as those of ordinary clay? Mutable, alack! at the moment of achievement, of accomplishment, when the grim destroyer must even bid the artist "stand." Passionately loved, Henrietta Montalba is no less passionately mourned. Her loss, a double one as an artist and a woman, is a loss to each and all of us. In the Belle Arti there is an empty place, in the long sala of the Palazzo Trevisazz there is an emptiness which cannot be filled. For what is taken, what is removed by so rare a personality, even we, who stand far off, can almost gauge. "Unto me no second friend," says the poet, and though the secret of the stricken be sacred, must not a like cry go out from such as had a common purpose, a common purse, a common home — from such as were not merely sisters, but life-long companions, fellow-workers, and loyal friends?

Link to Related Material

Bibliography

Hepworth-Dixon, M. "Henrietta Montalba: A Reminiscence." The Art-Journal (new series 1894): 215-217. HathiTrust, from a copy in the Getty Research Institute. Web. 1 August 2024.

Created 1 August 2024