All the photographs here are by Derek Kendall, © English Heritage. They were kindly provided by Atlantic Publishing, and come from the book under review. [Click on the images for larger pictures; click on the links for more pictures and information from our own website.]

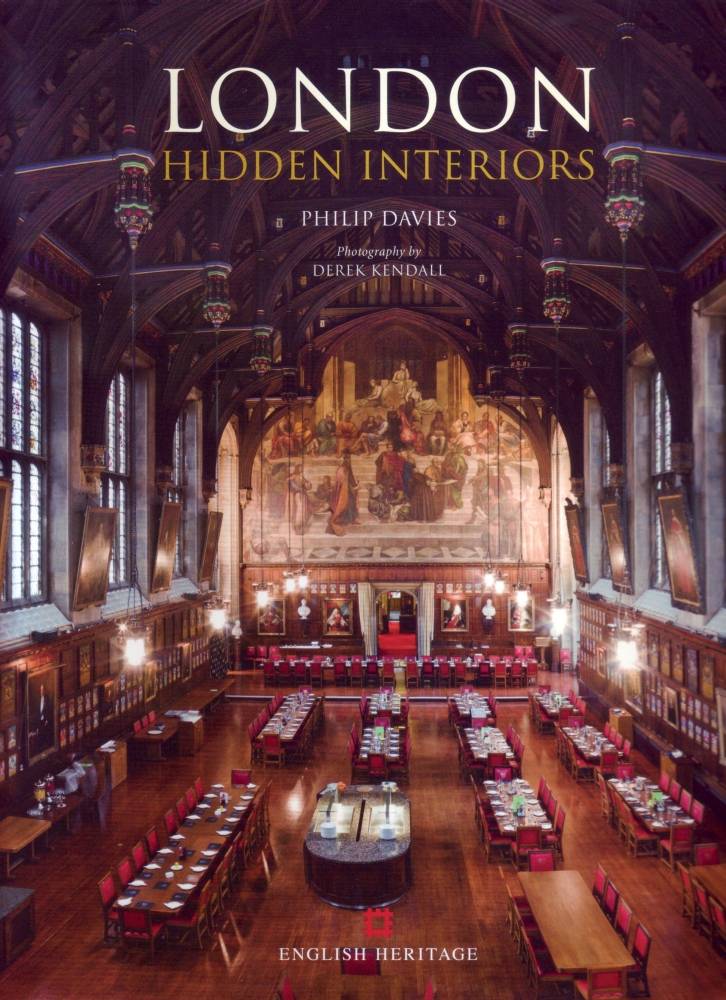

Cover of the book under review, showing the magnificent interior of Lincoln's Inn New Hall (1842-45), the work of the architects Philip and Philip Charles Hardwick. Its apparently hammerbeam roof is "actually hung from metal rods with painted pendant beam ends" (154), and the hall is overlooked at the north end by G.F. Watts's huge fresco, The School of Lawgivers.

London: Hidden Interiors is an exceptional book, one that invites superlatives. Taking us behind the closed doors of many of London's most noteworthy buildings, it is itself a work of art, probably indeed "the most highly illustrated book about London ever published" (35) — or ever likely to be published. Philip Davies's earlier Lost London 1870-1945 (2009) and Panoramas of Lost London (2011), are eye-openers too. They mourn the terrible losses to the built environment resulting from insensitive early twentieth-century rebuilding, both before and after World War II, and provide a unique photographic record of places we can never visit again. But Davies himself helped to reverse the trend. As Planning and Development Director for London and the South-East with English Heritage, he set up the "Buildings at Risk" register, and spearheaded the campaign to preserve London's squares. Now he feels able to celebrate rather than mourn, saying: "Architectural conservation is one of the great cultural success stories of the past century" (13). He goes on to prove his point by introducing and giving commentaries on 180 interiors, each photographed comprehensively by Derek Kendall, many of them showing what has survived from the past, often conserved and restored at great cost. Along with these treasures, Davies and Kendall reveal a range of more recent interiors, the work of new generations of formidably talented and creative designers.

View from behind one of the Palace of Westminster's four clock faces, in what is now properly called "Elizabeth Tower." Davies tells us that "[e]ach dial contains 312 panes of opalescent glass with 2-foot high numerals designed by Pugin" (37).

Among the many Victorian buildings featured, the most iconic is the Palace of Westminster, with the familiar landmark of St Stephen's Clock Tower. Recently renamed to mark the Queen's Diamond Jubilee, it is still best known simply as the home of London's famous hour-bell, Big Ben. Indeed, the tower itself is often affectionately termed Big Ben. Completed in 1858, its design was A. W. N. Pugin's last and most famous work. Here it is shown mainly from the inside, with dramatic views up through the centre of its square 334-step staircase, and from right behind one of its four clock-faces. The bell itself is also shown, along with some of its mechanisms, and so is the grim-looking lower part of the tower, once used for confining miscreants. Matching Kendall's intriguing views, Davies's account of it is lively and informative, though he only quotes the beginning of poor Pugin's note about it: "I never worked so hard in all my life for Mr Barry [Charles Barry, the architect with whom he was collaborating]" (36). No doubt Davies deemed the rest of the sentence to be unbearably poignant, betraying as it does both Pugin's passionate inwardness with his creations, and his confused mental state: "for tomorrow I render all the designs for finishing his bell tower & it is beautiful & I am the whole machinery of the clock," he added (qtd. in Hill 482). Genius exacts a terrible toll.

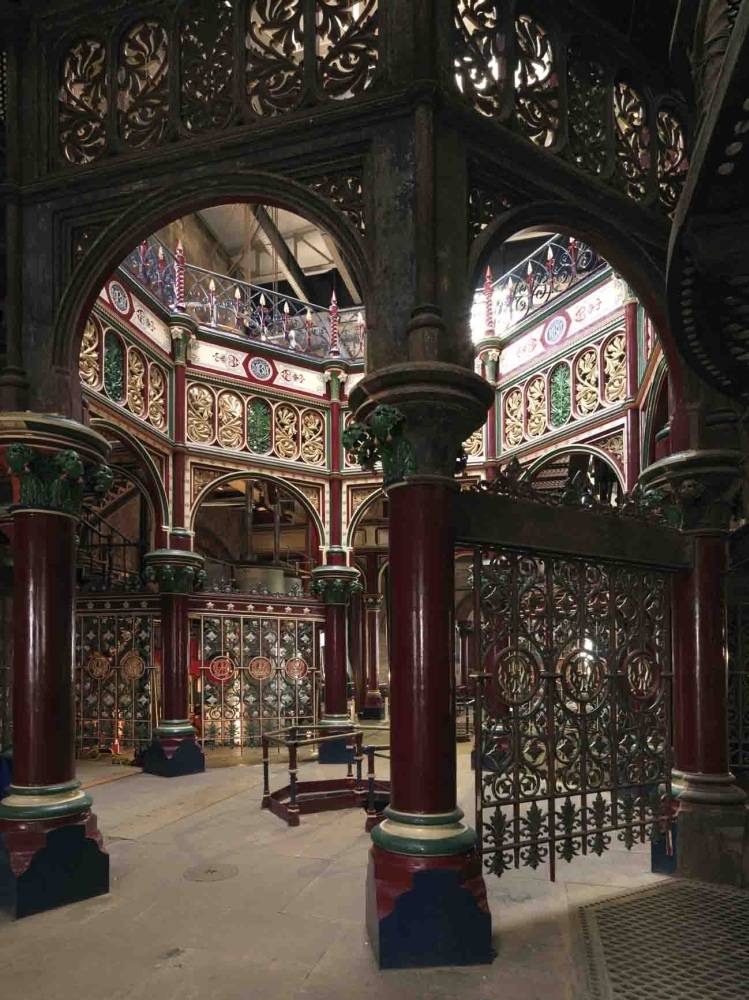

Left: The exterior of Crossness Sewage Works, in "plain grey gault and red brick" (348). Right: The contrasting interior of the engine house, with its gorgeously painted ironwork.

More surprising choices are the early industrial buildings included here. No one would expect to find a sewage works featured, for example. Yet there is one. In fact, a full-page photograph of the Engine House at the Grade 1 listed Crossness Sewage Works provides one of the lead-in pictures at the beginning, as well as being part of a two-page spread about the the building later on. Opened by the Prince of Wales in 1865, Crossness in south-east London was designed by Joseph Bazalgette and the architect Charles Henry Driver (1832-1900), to pump the the foul water diverted from the metropolis into the Thames. It was, as Davies explains, "a crucial component of the most important public infrastructure ever built in London," its engine house itself being "a veritable cathedral of ironwork.... a wonderful expression of the exuberance and confidence of the Victorian age" (348). It might seem amusing, even disrespectful, that the four great beam engines should have been named Prince Consort, Victoria, Albert and Alexandra, but it was an honour at that time, for these mechanisms were of vital importance to the welfare of the capital. Fascinating details from social history add to our appreciation of the main picture, which shows the huge progress made, with the help of English Heritage and the Heritage Lottery Fund, in restoring the Works.

Left: The exterior of the former Sion College near Blackfriars Bridge, designed by Sir Arthur Blomfield, and opened by the Prince of Wales in 1886. Right: The handsome former library, now used as a massive open-plan office.

A local MP, or a Member of the House of Lords, can help to arrange a visit to Big Ben's clock-tower, and the Crossness Engine House has several public "steaming" day each year. Initiatives like the London Open House weekend in September have made a variety of choice interiors, such as those in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, more accessible too. But one of the great virtues of this book is to alert readers to places they would never even have thought of visiting. These might be quirky little shops like James Smith & Sons in New Oxford Street, dating from 1857, or richly decorated pubs like the Black Friar of 1875, still flaunting a highly inventive Arts and Crafts interior on its narrow slice of land near Blackfriars Bridge. Other buildings have lost their original functions, though, and are less accessible. An important example here is the former Sion College on the Victoria Embankment. Sir Arthur Blomfield's "Perpendicular Collegiate Gothic style" (294) building of 1886 now houses a global investment partnership: Kendall shows us employees developing their financial strategies at desks in what was once the library, beneath a real hammerbeam roof and clerestory windows, perhaps inspired by their august environment..

Left: The Lloyd's Register of Shipping's dramatic entrance hall at 71 Fenchurch Street, introducing "a spectacular sequence of richly decorated processional space" (254). Right: Frank Lynn Jenkins' Spirit of British Maritime Commerce at the top of the staircase.

The variety of styles here is truly extraordinary. Lloyd's Register of Shipping's architect, Thomas Edward Collcutt, was a contemporary of Blomfield's, but this Grade II* listed building, completed in 1901, could not be more different from the Thames-side college. It is in what Davies describes as "an exuberant Arts and Crafts Baroque style" (254), and expresses, both outside and in, the leading role of Britain in the world of shipping. The rich architectural sculpture can be admired from outside, but Davies and Kendall allow us to experience the fabulous interior, taking us past the boldly chequered floor-tiling in the marble-lined entrance hall, and up the stairs to the widely vaulted landing on the first floor. Frank Llynn Jenkins' Spirit of British Maritime Commerce greets us here, the very epitome of the New Sculpture with its mixed materials (painted Carrara marble and lustrous bronze), and Art Nouveau sinuousness. The same sculptor's bronze relief runs round the walls here. Set with ivory, turquoise and mother-of-pearl, it shows the rewards of risking the high seas for trade.

The lavishly decorated General Committee Room of Lloyd's Register of Shipping, with work by Gerald Moira, Bertram Pegram and William de Morgan.

Jenkins' frieze is punctuated by doors into other "hidden interiors," notably that of the General Committee Room. Despite the formality of the semicircular seating, this room has a wonderfully celebratory feel. Much of this comes from the painted decoration by Gerald Moira (1867-1959), who also collaborated with Jenkins at the Trocadero in Piccadilly. Above richly coloured marble columns glows the barrel-vaulted ceiling, with its array of signs of the zodiac — motifs also used, for example, on the dome over the Grand Staircase in the Foreign Office, but here with the representations of the four elements, of obvious relevance to the fortunes of shipping. On either side of the semicircular pediment are harpists, and above the fireplace with its bronze panels is a white marble relief by Bertram Pegram, which we are told was only uncovered during recent restoration work. This would seem to be the one referred to by Clare Willsdon as "an allegorical marble overmantel ... representing Lloyd's 'influence over Shipbuilding'" (347), though Willdon attributes it to Bertram's cousin Henry. Around the fireplace itself are William de Morgan tiles. No wonder Davies sees this room as the "climax of the entire interior" and "one of the finest architectural spaces in the capital" (256).

The happy co-existence of old and new, the way each enhances the other, is brilliantly illustrated here by the juxtaposition of Collcutt's building with the Richard Rogers Partnership's one for Lloyd's of London on nearby Lime Street. Famous for looking "inside-out," the latter was completed in 1986, and was much more revolutionary for its time. It still looks remarkably futuristic, and is among the select few of its era to be listed Grade I. As Davies says, and Kendall so dramatically shows, the extraordinarily high central atrium there is awe-inspiring. Still, the General Committee Room at the Register is by no means overshadowed by it. This is not an isolated instance. The kind of harmony achieved when this whole complex was redeveloped is exemplified inside Lloyd's of London itself, where a whole dining room by Robert Adam has been reconstructed on the ninth floor, as a board room: "The delicate plasterwork details and pastel colour scheme forms a surreal counterpoint to the High Tech building in which it sits," comments Davies, adding that this just "epitomises the City's ability to retain tradition alongside cutting-edge modernity" (258). It is not an isolated example. Consider, for instance, E. M. Barry's touchingly beautiful neo-classical chapel nestling inside Great Ormond Street Hospital, with its state-of-the-art facilities, or the courtrooms carefully preserved despite the new staircase and new level flooring of the Supreme Court building (the former Middlesex Guildhall).

This book is almost as inexhaustible as London itself. It is simply impossible to do justice to it by picking out a small selection of what it features. Within the Victorian era itself, Davies shows the stunning interiors of places of worship like St James the Less in Vauxhall and the Bevis Marks Synagogue in the East End, as well as the lavishly decorated foyers and rooms of clubs, hotels, theatres and galleries. Museums, hospitals, prisons and many other types of buildings, including private houses, are all represented too, with a wealth of useful background information. Outside the Victorian period are some wonderfully exotic interiors. The Arab Hall at Lord Leighton's house in Kensington, glowing inside "with all the gorgeous extravagance of the East" (398), does give a foretaste of the architectural fruits of multiculturalism. More authentic, however, are the shimmering main prayer hall of the London Central Mosque next to Regent's Park, the brilliantly painted Shrine Hall of the Buddhapadipa Temple in Wimbledon, and the intricately-carved individual shrines of the Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Neasden — "the first traditional Hindu temple to be built in Europe, and the largest outside India" (422). Davies is as impressively knowledgeable in this specialised area as in others. The twentieth century also has interiors with no precedents at all: the gleaming Art Deco Silver Gallery of the Park Lane Hotel, for instance, or the eerily deserted Kingsway Tram Subway, or even the Stockwell Bus Garage, "at the time of its construction in 1952 ... the largest area under a single roof in Europe" (374).

Through such a wide range of examples, organised roughly geographically (spiraling out of central London to its further reaches), Davies and Kendall offer us a splendid opportunity to see the spaces created for us by the capital's, and indeed the country's, sometimes even the world's, most inspiring civil engineers, architects, interior designers and craftsmen. In the process of looking, we learn much about London's history and social history. All such spaces, from the plushest, most intimate room to a vast transport hub, tell us something about ourselves as well. We spend most of our time in more ordinary contexts, but these special ones all represent different aspects of our shared culture. Entering into the more highly crafted spaces, we can extend and enrich ourselves, elevated by the visions of those who made them, and by our own responses to those visions. What we are surrounded by, and what we choose to have around us, is part of who we are. It repays just the kind of study, thoroughly enjoyable in itself, that every page of this outstanding book promotes.

Bibliography

(Book under review) Davies, Philip. London: Hidden Interiors. London: Atlantic Publishing, 2012. 448pp. in large (290 x 245mm) format. £40. ISBN 978-0-7112-2941-9.

Hill, Rosemary. God's Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2008.

Willsdon, Clare A. P. Mural Painting in Britain 1840-1940: Image and Meaning. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Last modified 12 December 2012