he ceramics manufactured during the Aesthetic

Movement emphasise many of its most significant aspects.

The nature of the materials used and the comparatively

simple technical processes involved made pottery an ideal

outlet for the creative fervour of artists, both professional

and amateur, which characterises the period. At the same

time the established ceramics industry also responded to

the clarion call of Art, and, in meeting the enthusiastic

demand for the "Japanesque," entered its most original and

spectacular phase of the nineteenth century.

The products of the potters, whether they emanated from

the art-potteries or from the factories of Worcester and

Stoke, were for the most part objects for contemplation,

to adorn the mantelpiece or the ledges and platforms of

the art-furniture cabinet, the most characteristic furniture

form of the Aesthetic Movement.

he ceramics manufactured during the Aesthetic

Movement emphasise many of its most significant aspects.

The nature of the materials used and the comparatively

simple technical processes involved made pottery an ideal

outlet for the creative fervour of artists, both professional

and amateur, which characterises the period. At the same

time the established ceramics industry also responded to

the clarion call of Art, and, in meeting the enthusiastic

demand for the "Japanesque," entered its most original and

spectacular phase of the nineteenth century.

The products of the potters, whether they emanated from

the art-potteries or from the factories of Worcester and

Stoke, were for the most part objects for contemplation,

to adorn the mantelpiece or the ledges and platforms of

the art-furniture cabinet, the most characteristic furniture

form of the Aesthetic Movement.

The earliest art-pottery was decorative stoneware manufactured, from 1866, at Doulton's Lambeth pottery. Its production was suggested by the connoisseur and medievalist Edward Cresy, and its early forms were inspired by the grès de Flandres of the Middle Ages. Artistic stoneware, produced also at C. J. C. Bailey's Fulham Pottery and by the Martin Brothers, indicates the elision between progressive elements of the Gothic revival and the earliest manifestations of the Aesthetic Movement. Significantly, Robert Wallace Martin had been an assistant working on the sculpture of Pugin's Houses of Parliament, and J. P. Seddon designed stoneware for C. J. C. Bailey.

Painted ceramics is another category of art-pottery. It includes work produced at Minton's Art-Pottery Studio in Kensington Gore, Doulton's Lambeth Faience, tiles painted by many eminent artists (and the anonymous ones employed by W. B. Simpson and Sons), as well as work, both amateur and professional, produced for Howell and James's annual exhibitions of "Painting on Pottery and Porcelain" (from 1875). Painting on pottery and porcelain, like painting on furniture, reflects the desire of the intelligentsia, following the precepts of Ruskin and the example of Morris, to invest ordinary things with Art (sometimes, one feels, as a substitute for design). The pottery made by Theodore Deck and painted by such artists as Félix Bracquemond and Eléonore Escallier which was exhibited at the Paris Exhibition of 1867 provided the stylistic precedent, rather than the pottery painted for Morris and Co. and the work of William de Morgan.

Other art-pottery was decorated with slip in the long-standing tradition of English pottery, particularly of the seventeenth century. In Barnstaple, Brannam and Lauder revived the decorative slipware of North Devon, covering their wares with sgraffito designs in the current stylistic idiom. The Watcombe Pottery at Torquay added slipware to their already acclaimed terracotta. Edmund Elton at Clevedon near Bristol, decorated his art-pottery with designs of flowers and birds in coloured slip. This form of decoration was the equivalent in pottery to "Old English" in the field of furniture and interior decoration. At the Linthorpe Pottery, Middlesbrough, established in 1879, Christopher Dresser and Henry Tooth developed a class of art-pottery which depended for its aesthetic effect on its forms and colours. Coloured glazes and bold forms, generally left unadorned but sometimes decorated with incised geometrical ornament, characterise Linthorpe Ware, Bretby Art Pottery (produced by Tooth after he left Linthorpe in 1884), and Burmantofts Faience. This is the art-pottery which makes the most radical break with the style of High Victorian ceramics, and which looks forward to the work of such potters as Bernard Moore, Howson Taylor, Charles Vyse and Reginald Wells.

The Cult of Japan and the Anglo-Japanese Style

The most pervasive stylistic influence on the ceramics of the Aesthetic Movement, both on art-pottery and on industrial production, was japonaiserie. The displays of Japanese craftsmanship at South Kensington in 1862 and at Paris in 1867 had enormous impact. Even by 1866 the Royal Worcester Porcelain factory was producing wares in the Japanese style, and Minton's and most other leading manufacturers soon followed suit. At its most feeble japonisme appeared in the decoration of traditional forms of Western pottery with a profusion of Japanese motifs -- prunus blossom, pine branches, storks and roundels. But the best work in the Japanese style reflected not only the high standard of Japanese craftsmanship, but also the originality of imagination brought to design and decoration by the Japanese artist. Direct imitation of Japanese pottery originals by English manufacturers was rare. Indeed the best of the "Japanesque" were made at Worcester was inspired by Japanese work in metals, lacquer and ivory, while Minton's tour de force in the Japanese style was their porcelain, decorated with gilding and enamels, inspired by Oriental cloisonné ware.

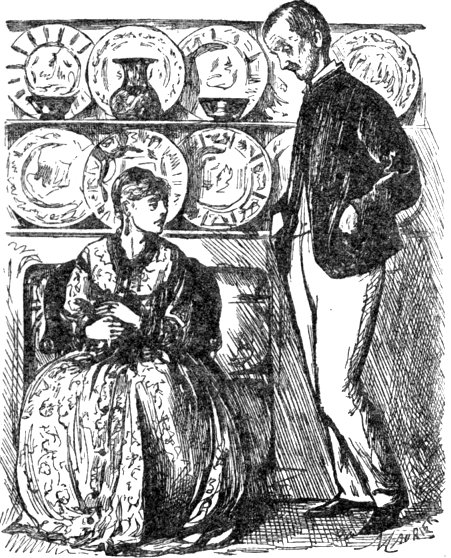

Punch on the Aesthetic Movement's emphasis upon ceramics. Left: The Passion for Old China. Middle: Acute Chinamania. Right: Chronic Chinamania (incurable). [Click on thumbnails for larher images.]

Art-pottery, too, provides instances of Japanese influence as diverse as the drawing style of Hannah Barlow and the geometrical forms of some pieces designed by Christopher Dresser for Linthorpe. The grotesques by Mark V. Marshall and R. W. Martin at once reveal a familiarity with Japanese art and point the connections between Gothic and Japanese in the artistic mind of the Aesthetic Movement. The medieval aspects of Japanese art and society were stressed by contemporary writers. During the Aesthetic Movement a great deal of artistic talent was applied to the decoration of ceramics: W. S. Coleman, H. Stacy Marks, E. Burne-Jones and J. Cazin were among the accomplished painters who worked in the medium, while the quantity of amateur contributions to the Howell and James exhibitions demonstrates the intensely felt need for artistic craft activity of a generation brought up on 'The Nature of Gothic'. Other artists were not inhibited by any lack of formal training from turning their creative endeavours to the manufacture of pottery:

De Morgan, Elton, Tooth. An almost symbolic figure of the period was the chemist Professor Church who, with his technical advice, sometimes given personally (for instance to Doulton, Elton and, while on holiday in the south of France, to Massier), and to all in his numerous lectures which were printed in the leading artistic periodicals, fulfilled the positivist ideal of Science combining with Art. Great stress was laid by the critics of the day when writing their notices of art-pottery exhibitions on the number of women employed in its manufacture or decoration. The lack of what Howell and James called "graceful, appropriate and at the same time profitable employment for ladies" was a serious social problem which remained until the days of Ann Veronica. More serious was the economic depression which hit industry in the late '70s; it was in response to this that, for example, the Sun Brick Works was transformed into the Linthorpe Art Pottery and that work on the production of architectural terracotta at John Wilcock's Leeds factory was supplemented by the introduction of Burmantofts Faience. Combining elements of amateurism and philanthropy, and representing the gamut of stylistic eclecticism, the ceramics of the Aesthetic Movement faithfully delineate the features of an outstanding cultural epoch.

Galleries of Related Materials

References

Haslam, Malcolm. "Ceramics" in The Aesthetic Movement and the Cult of Japan. London: The Fine Art Society, 1972. Pp. 21-22.

Landow, George P. The Art-Journal, 1850-1880: Antiquarians, the Medieval Revival, and The Reception of Pre-Raphaelitism." The Pre-Raphaelite Review 2 (1979), 71-76.

The Fine Art Society, London, has most generously given its permission to use information, images, and text from its catalogues in the Victorian Web, and this generosity has led to the creation of hundreds and hundreds of the site's most valuable documents on painting, drawing, sculpture, furniture, textiles, ceramics, glass, metalwork, and the people who created them. The copyright on text and images from their catalogues remains, of course, with the Fine Art Society. [GPL]

Last modified 10 April 2013