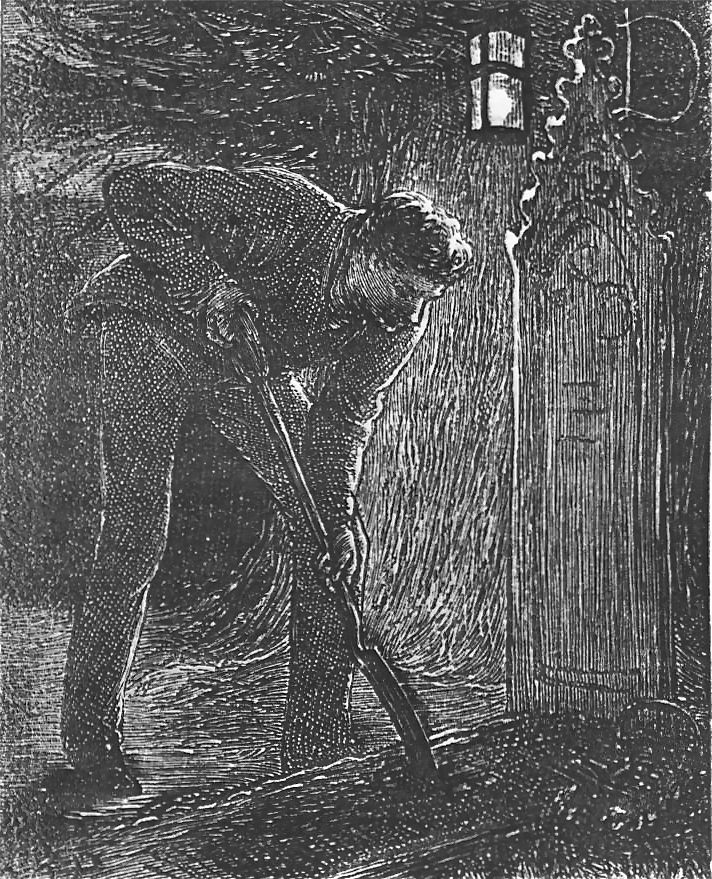

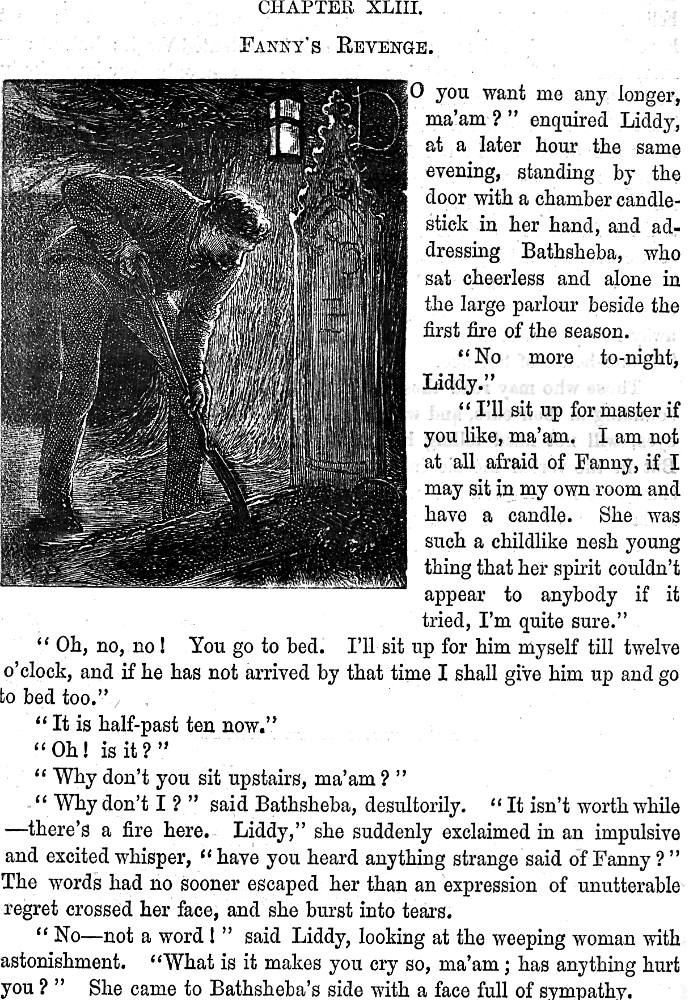

Her Tears Fell Fast in Chapters 43 ("Fanny's Revenge.") through 47 ("Adventure by the Shore.") in Vol. 30: pages 490 through 512 (24 pages in instalment); plates: initial "D" (6 cm wide by 7.6 cm high) signed "H. P." in lower-left corner. Facing page 490, vertically-mounted, 16 cm wide by 10.1 cm high, signed "H. Paterson" in the lower-left corner. The wood-engraver responsible for this illustration was Joseph Swain (1820-1909). [Click on the image to enlarge it; mouse over links.]

Above: The initial-letter vignette and first full page of the tenth instalment of the story: D in Far FRom the Madding Crowd (Vol. XXX).

Commentary

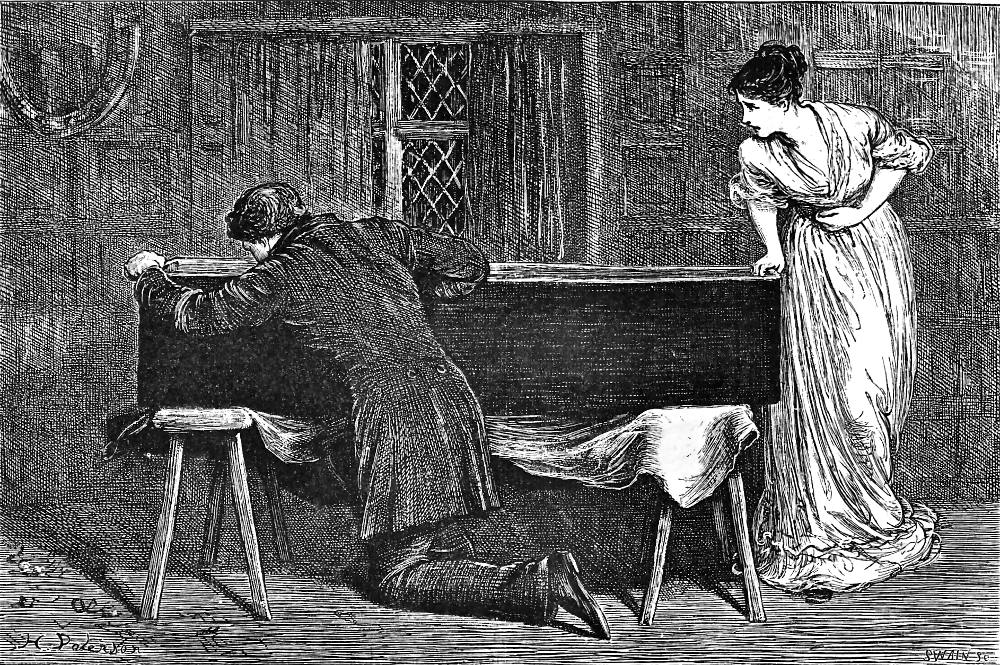

The title of the first chapter in the October instalment, "Fanny's Revenge," implies that the young servant-girl was not so much a woman 'fallen' as neglected, abandoned, and wronged, so that what subsequently befalls Troy for his shoddy treatment of Fanny is nemesis, which she herself effects from the grave. Although the vignette is uncaptioned and although the viewer will have to turn the page clockwise to read the full-scale plate's caption "Her Tears Fell Fast Beside the Unconscious Pair," that Troy will weep at Fanny's coffin in his wife's presence and that he will dig at Fanny's grave are clearly telegraphed, and that there will be an irreparable rupture in his relationship with Bathsheba is strongly implied. In fact, the only plot developments in the tenth instalment for which the illustrations do not prepare the reader are Troy's purchasing the headstone and his swim in the cove (and subsequent rescue by a shore party from a brig in the English Channel).

[E]ven in scenes where melodrama is unavoidable, Allingham controls the situation, and actually stresses psychology rather then [sic] heightened, exaggerated dramatic moments of the text itself. In the scene . . . which depicts Troy leaning onto the coffin to kiss the lips of Fanny Robin, emphasis divides between the grieving Troy and a deeply disturbed Bathsheba. Troy has the central position in the engraving, and the sweeping lines of his kneeling figure, the grip of his hand on the coffin's edge, reveal his agony. But Troy's dark suit blends into the darkness of the coffin (an interesting omen), while Bathsheba's white dress, as well as her position at the edge of the frame, sets her apart from the scene she is unwillingly comprehending. Bathsheba's emotions, as well as Troy's, are suggested through hand and general body position. [Jackson 81]

Since the viewer cannot assess Troy's facial features, the Helen Paterson Allingham is in effect requiring the reader to construct them from clues in the letter-press and from sympathetic imagination. Prostrate with grief, too late has Troy determined to show his concern for Fanny, his black garments suggesting deep mourning in a very public way. However, hours later, when he purchases the headstone, the mortuary-seller notices that his customer is wearing "not a shred of mourning" (p. 504), so that the dark mourning suit is an Allinghamic contrivance, as indeed are the title and the composition of the whole plate. Paterson is apparently illustrating the following passage in the middle of Ch. 43: "Her tears fell fast beside the unconscious pair: tears of a complicated origin, of a nature indescribable, almost indefinable except as other than those of simple sorrow" (p. 494). Moreover, the "pair" to which the passage refers are Fanny Robin and her infant, for the moment described is that when, having opened the coffin, Bathsheba realizes that the girl was carrying Frank's child. Shortly afterward, Frank returns home, still ignorant of Fanny's death. In short, the plate is a visual cheat designed to create an effect different from that of the text, an effect that entirely omits Fanny's dead infant.

Thus, in Ch. 43 Troy advances toward the coffin (and epiphany) after Bathsheba has already learned that Fanny had a child, despite Oak's effort to prevent her from learning the fact: "Troy looked in, dropped his wife's hand, knowledge of it all came over him in a lurid sheen, and he stood still" (p. 495). Gradually he sinks to his knees to assume the position that Paterson has realised in the plate while Bathsheba watches her husband "from the other side [of the coffin], still with parted lips and distracted eyes" (p. 495). At the top of page 496 Troy is disposed as in the plate, although Bathsheba is probably on the other side of the coffin. Thus, in shifting the narrative focus from Troy to Bathsheba Paterson in her October plate offers a synthesis of two textual pages; she has invented rather than recorded a scene in order to balance the figures, to contrast their postures, and to reveal Bathsheba's rather than Troy's emotional state. Since the plate's "unconscious pair" are Troy and Fanny rather than mother and child, the illustration reflects a distorted and perhaps even slightly Bowdlerized version of the text.

While Jackson erroneously celebrates the October full-page plate as being grounded in a specific textual moment and assiduously avoiding the melodramatic (although Bathsheba's gripping herself as her torso bends and twists forward in subtle contraposto and Troy's prostrate form certainly imply the heightened emotion and tableau vivant 'frozen moment' of the Victorian theatre), and lauds the October vignette as admirably conveying Troy's frenzied reaction to Fanny's death (though neither his stooping form nor mask-like face betray any such emotion) rather than realising a specific textual moment, this critic is highly dismissive of the November full-scale plate, which she regards as a superfluous elaboration of the swimming incident at the end of the last episode:

Troy's 'drowning' appears as only a distant spectacle in the single illustration that emphasizes nature rather than the human element. Troy's figure, in fact, is the least interesting item in the scene, as the human figure is dwarfed by the surrounding cliffs, but even here the panoramic landscape lacks interest because of its flat and wooden delineation. The actual choice of scene, however, presents a puzzle. Troy's supposed drowning occurs in the previous instalment (for October), and the reader is not aware at that time that a witness exists for the event. In the November number, the reader belatedly learns that a witness does exist, and that he has reported the drowning. Yet the fact of observation really adds nothing to the suspicions of his 'death' that already exist, particularly in Bathsheba's own mind. [Jackson 81-82]

However, at the end of the October instalment we have every expectation that the brig will deliver Troy to the nearest English port, Budmouth, and that, should he choose not to return to Weatherbury, his disappearance will not be equated legally with his death. The scene convinces the reader much more effectively than Hardy's scant reference to young Dr. Baker's account of Troy's being swept away by the current that the story's principals are fully entitled to believe Bathsheba's husband dead. The plate is not "anti-climactic" because the previous episode shows Troy safe and well after his ordeal; rather, the plate contributes to the irony of Boldwood and Bathsheba's assumption that Troy is dead and that she will eventually be free to re-marry (even though no body has been found), while the reader knows that Troy is alive.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy. Volume One: 1840-1892; Volume Three: 1903-1908, ed. Richard Little Purdy and Michael Millgate. Oxford: Clarendon, 1978, 1982.

Hardie, Martin. Water-colour Painting in Britain, Vol. 3: The Victorian Period, ed. Dudley Snelgrove, Jonathan Mayne, and Basil Taylor. London: B. T. Batsford, 1968.

Hardy, Thomas. Far From the Madding Crowd. With illustrations by Helen Paterson Allingham. The Cornhill Magazine. Vols. XXIX and XXX. Ed. Leslie Stephen. London: Smith, Elder, January through December, 1874.

Holme, Brian. The Kate Greenaway Book. Toronto: Macmillan Canada, 1976.

Jackson, Arlene M. Illustration and the Novels of Thomas Hardy. Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1981.

Turner, Paul. The Life of Thomas Hardy: A Critical Biography. Oxford: Blackwell, 1998, 2001.

Created 12 December 2001 Last updated 25 October 2022