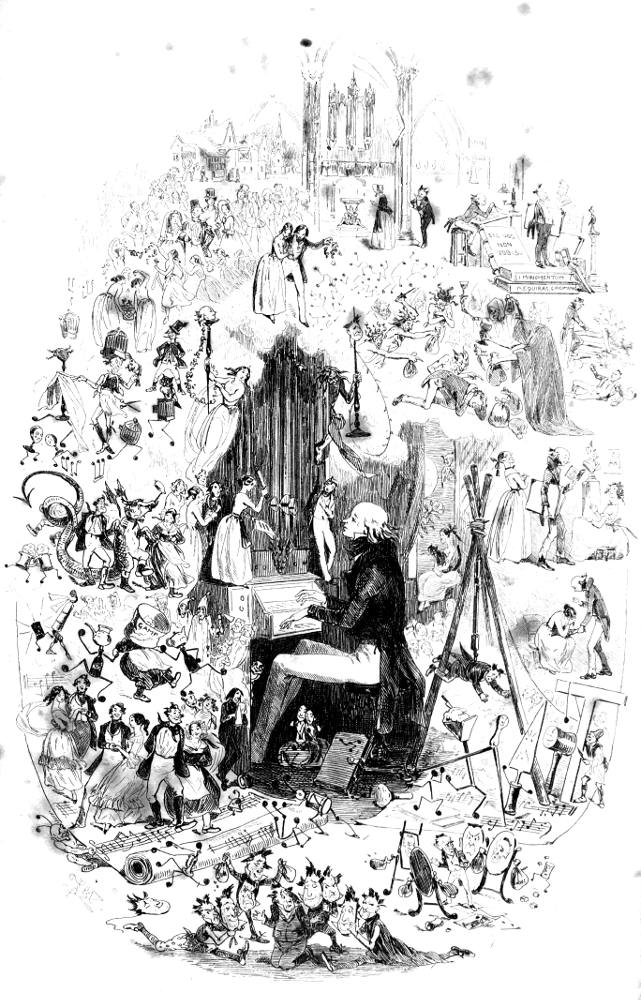

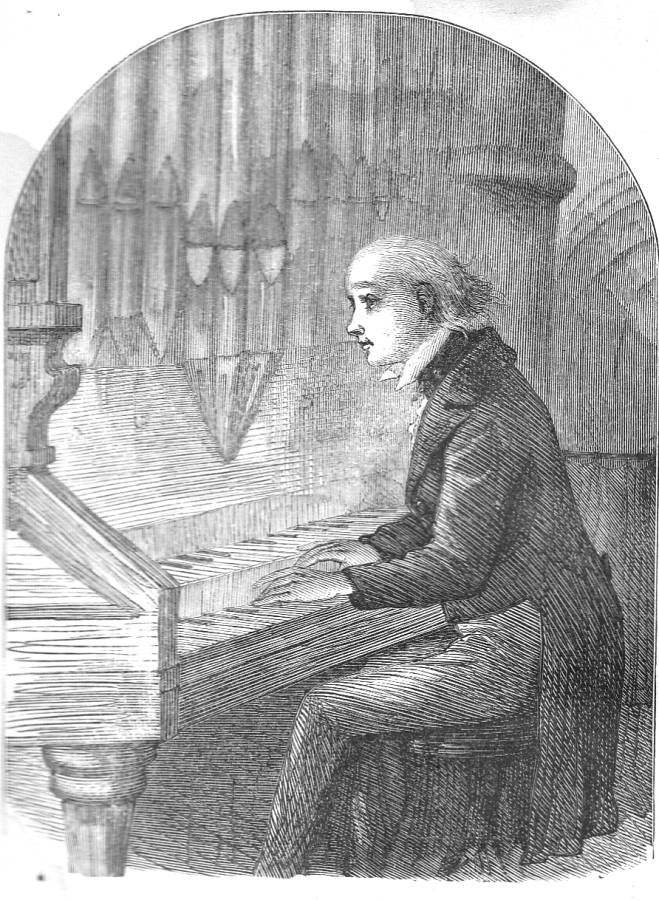

Tom's Reverie. (1872). Fifty-ninth and final composite woodblock illustration by Fred Barnard for Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit (Chapter LIV), page 423. [This is a melancholy and stark contrast to the lively baroque complexity of Phiz's final illustration thirty years earlier. As in the letter-press, Tom touches the notes of his organ lightly. However, Fred Barnard departs from Dickens's text by including the shadowy figures of Martin and Mary in the background. According to Barnard's interpretation, Tom never recovers from his unrequited love for Mary Graham, but enjoys the love and companionship of his friends' children.] 9.3 cm high by 13.8 cm wide (4 ¼ high by 5 ½ inches). Running head: "A Dear Old Friend." [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: Dickens's Apostrophe to Tom Pinch, Musician

What sounds are these that fall so grandly on the ear! What darkening room is this!

And that mild figure seated at an organ, who is he! Ah, Tom, dear Tom, old friend!

Thy head is prematurely grey, though Time has passed thee and our old association, Tom. But, in those sounds with which it is thy wont to bear the twilight company, the music of thy heart speaks out: the story of thy life relates itself.

Thy life is tranquil, calm, and happy, Tom. In the soft strain which ever and again comes stealing back upon the ear, the memory of thine old love may find a voice perhaps; but it is a pleasant, softened, whispering memory, like that in which we sometimes hold the dead, and does not pain or grieve thee, God be thanked.

Touch the notes lightly, Tom, as lightly as thou wilt, but never will thine hand fall half so lightly on that Instrument as on the head of thine old tyrant brought down very, very low; and never will it make as hollow a response to any touch of thine, as he does always.

For a drunken, squalid, begging-letter-writing man, called Pecksniff (with a shrewish daughter), haunts thee, Tom; and when he makes appeals to thee for cash, reminds thee that he built thy fortunes better than his own; and when he spends it, entertains the alehouse company with tales of thine ingratitude and his munificence towards thee once upon a time; and then he shows his elbows worn in holes, and puts his soleless shoes up on a bench, and begs his auditors look there, while thou art comfortably housed and clothed. All known to thee, and yet all borne with, Tom! [Chapter LIV, "Gives the Author Great Concern. For it is the Last in the Book," 422.

Commentary: Mildly Melancholy Tom, Perpetual Bachelor

"I have a notion of finishing the book, with an apostrophe to Tom Pinch, playing the organ." — "Dickens to Phiz," June 1844.

Furniss's illustration of Tom Pinch at the organ, the 1910 volume's last, is his re-interpretation of a similar illustration in the final monthly number of the Chapman and Hall serialisation, Hablot Knight Browne's Frontispiece for Chapter LIV (Parts Nineteen-Twenty, July 1844), as well as of Fred Barnard's final illustration, a dark plate to end one of the greatest comic novels in the twenty-two volume Household Edition. The July 1844 plate seems to violate Phiz's governing principle for his series of forty steel engravings since he has distributed rewards and punishments according to the concept of Nemesis, or poetic justice. Phiz's plate emphasizes Dickens's ultimate isolation of Tom, leaving him outside “the magic circle” of the Victorian novel’s typical happy ending: romance, marriage, children, that the virtuous protagonist such as Martin receives as a consequence of his having striven to do the right thing. Yet Phiz has at least made Tom the organist the centre of a vortex, surrounding him with the other characters in the story. Barnard and Furniss have both responded, in their own ways, to Phiz's original conception of Tom as the solitary organist.

Furniss's approach is much closer to that of Barnard's Tom's Reverie in that it is sombre and static. For Dickens and Phiz, despite the fact that Tom's organ-playing has been purely incidental to the plot and to his character, his inspired musicianship serves as the central image of the frontispiece of the July 1844 "double" number (Parts 19 and 20) — one of the last illustrations executed but one of the first that the reader of the 16 July 1844 volume would have seen. All the nineteenth-century illustrators of the novel (Phiz, Eytinge, Barnard, and Furniss) concur that Tom is playing the church organ, and seem to imply that this image represents the inspired artist's contemplating his own mortality, his work, his life thus far, and his relationships with the other characters in the novel; the artistic conception of Tom as musician, performer, and perhaps even composer eventually will blend into illustrator R. W. Buss's memorial to Charles Dickens as a highly prolific author, Dickens' Dream (1875), which makes explicit the connection between the legion of characters that flowed from his pen and the man himself.

For strictly American readers Ticknor-Fields mid-nineteenth-century house artist for the 1867 Diamond Edition, Sol Eytinge, Jr., has depicted Tom as an organ soloist (probably inspired by Phiz's frontispiece) in a series of illustrations in which the other characters consistently appear in groups or pairs. However, Fred Barnard's approach in the 1872 Chapman and Hall Household Edition composite woodblock engraving Tom's Reverie on the very last page presents Tom as a social isolate. This image of Tom emphasizes his leaving behind his sister and brother-in-law (likely the shadowy figures in the background of this dark plate) and entering another sphere as his hands assume very specific places on the twin keyboards. Consequently, we might reasonably view Harry Furniss's 1910 interpretation of Tom as an imaginative response to Barnard's atmospheric but realistic 1872 composite woodblock engraving and Phiz's more fanciful 1844 invention.

Relevant Illustrations from Other Editions: 1844, 1867, and 1910

Left: Hablot Knight Browne's Frontispiece (July 1844), a perfect riot of poetic invention. Centre: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Phiz-inspired but much more realistic frontispiece for the Diamond Edition, Tom Pinch (1867), in which the artist is quite alone with his art. Right: Harry Furniss's Chapter LIV illustration foregrounds Tom as an instrumentalist who attends to both his music and his auditor, perhaps, then an exemplification of Dickens the novelist: "Touch the notes lightly, Tom" (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1844.

_______. Martin Chuzzlewit. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1863. Vols. 1 to 4.

_______. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_______. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit, with 59 illustrations by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872. Vol. 2. [The copy of the Household Edition from which this picture was scanned was the gift of George Gorniak, Proprietor of The Dickens Magazine, whose subject for the fifth series, beginning in January 2008, was this novel.]

_______. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872. Vol. 2.

_______. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 7.

Guerard, Albert J. "Martin Chuzzlewit: The Novel as Comic Entertainment." The Triumph of the Novel: Dickens, Dostoevsky, Faulkner. Chicago & London: U. Chicago P., 1976. Pp. 235-260.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 15: Martin Chuzzlewit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 267-294.

Jackson, Arlene M. Illustration and the Novels of Thomas Hardy. Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1981.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

"Martin Chuzzlewit — Fifty-nine Illustrations by Fred Barnard." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington and London: Indiana U. P., 1978.

_____. "Martin Chuzzlewit's Progress by Dickens and Phiz." Dickens Studies Annual 2 (1972): 119-149.

Steig, Michael. "From Caricature to Progress: Master Humphrey's Clock and Martin Chuzzlewit." Ch. 3, Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978. Pp. 51-85. [See e-text in Victorian Web.]

Steig, Michael. "Martin Chuzzlewit's Progress by Dickens and Phiz." Dickens Studies Annual 2 (1972): 119-149.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Created 3 February 2008

Last updated 28 November 2024