In transcribing the following article I have used the Hathi Trust Digital Library’s generally accurate text (most of its errors take the form of extra spaces within words), and I have added a few subtitles to make reading easier. — George P. Landow

“Drawn by Florence Caxton”. Click on image to enlarge it.

o one seems to know at what period the ‘Postman’s Knock’ — that peculiarly decisive kind of ‘rapping’ — began to be specially heard on St. Valentine’s Day. Two or three quidnuncs have propounded this question, to be answered by other quidnuncs; but the answer has not yet come. As to the worthy saint himself, who lived sixteen hundred years ago, he appears to have been an unconscious originator of a system which has culminated in the sendlng of anonymous love-letters (sincere or satirical, as the case may be) on the 14th of February. At Rome, long before the Christian Era, there was a festival about the mlddle of February, during which the written names of young wo men were put into a box, and drawn out by the young men present, as a preliminary to a sort of chance love-making. The Christian priests in later ages, willing to divert the thoughts of the 'people into a different direction, substituted the names of saints for those of young women; but the people, finding this not half so exhilarating, reverted to their old practice. And so it gradually came about that, on or near the Feast of St. Valentine, young persons were accustomed to select their lovers and mistresses by a sort of lot or chance. In more recent times the custom spread to other countries, modified in its details. We learn from Chambers’s ‘Book of Days’—a storehouse of curious information not easily accessible elsewhere—that Misson, a learned traveller about two centuries ago, described a pretty custom as then prevailing in England and Scotland on the eve of St. Valentine’s Day:—‘An equal number of maids and bachelors get together; each writes their true or some feigned name upon separate billets, [178/179] which they roll up, and draw by way of lots, the maids taking the men’s billets, and the men the maids’; so that each of the young men lights upon a girl that he calls his Valentine, and each of the girls upon a young man whom she calls hers. By this means each has two Valentines; but the man sticks faster to the Valentine that has fallen to him than to the Valentine to whom he has fallen. Fortune having thus divided the company into so many couples, the Valentines give balls and treats to their mistresses, wear their billets several days upon their bosoms or sleeves; and this little sport often ends in love.’ There does not appear to be any antecedent partiality provided for in this programme: it is simply a love-lottery or raffle between the maidens and bachelors—‘all prizes and no blanks.’ And indeed destiny, or something distinct from mere will and determination, has often been accepted as the ruling power in this matter. It was an old English belief that the birds select their mates on St. Valentine’s Day; and that an influence or potency was inherent in the day which rendered in some degree binding the lot or chance by which any bachelor or maiden was at this time led to fix his or her attention on a person of the opposite sex. Another popular belief was, that the first maiden whom a bachelor might see, or vice versa, on the morning of the 14th of February, would be, not only the Valentine, but in good time the destined spouse; and hence sundry little cunning contrivances—such as lying in bed to a late hour, or looking the other way, or shutting the eyes—to insure that the first person seen should be some special or already-selected favourite. Herein a small attempt was made to circumvent Destiny by Inclination.

But the ‘Postman’s Knock’ is another aspect of the affair, and, as we have said, is not easily traceable to its origin. It is not known when the custom began of sending pictorial love-letters by post, with no signature to denote from whom they came. Comparatively modern it certain is. When we take into account the artistic and poetic quality of nine-tenths of these missives, we cannot escape the conclusion that St. Valentine has but little reason to be proud of his votaries. There are no direct means of ascertaining how many valentines are sent by post, or by any other channel; seeing that valentine-makers do not communicate to each other the extent of their trade, and that postmen are not authorized to peep too curiously inside the envelopes, even were they so inclined. The authorities at the General Post Office, about ten years ago, ascertained that, in the week containing the 14th of February, 800,000 more letters passed through the post than in the average of weeks about that period of the year; but we suspect that the valentines which are actually sent must now far exceed this number.

As for the productions themselves, as combinations of pictures and verses, they are pretty readily separable into three groups or classes — the elegant, the vulgar, and the sentimental. The elegant valentines are those which have come into fashion in recent years, since ornamental stationery has been produced in such excellence, and at the same time so cheaply. The vulgar valentines are those well-known caricatures of cooks, housemaids, nursemaids, coachmen, ‘Jeameses,’ gardeners, grooms, butlers, ‘buttons,’ policemen, tailors, tinkers, cobblers, &c.; servants and work people, extravagantly drawn and gaudily painted; and accompanied by verses about as good (or as bad) as the pictures: while some of the specimens at the lowest extremity of this group are so exceedingly gross as to be fit only for the dens of Holywell Street. The sentimental valentines have been humorously described thus :—‘Hearts transfixed by darts; turtle-doves apparently commiserating each other on the absurdity of the position they are made to occupy; a profusion of small fat boys, principally remarkable for their disinclination to patronize the cheap clothing establishments of the day—descendants, we always imagine, of our progenitors [179/180] the ancient Britons, whose costume was principally flesh-colour, with the addition of a little paint; pretty, but otherwise highly insipid young gentlemen; and mincing young ladies, looking fit for anything but useful domesticated wives.’

[The Manufacture of Valentines in Victorian England]

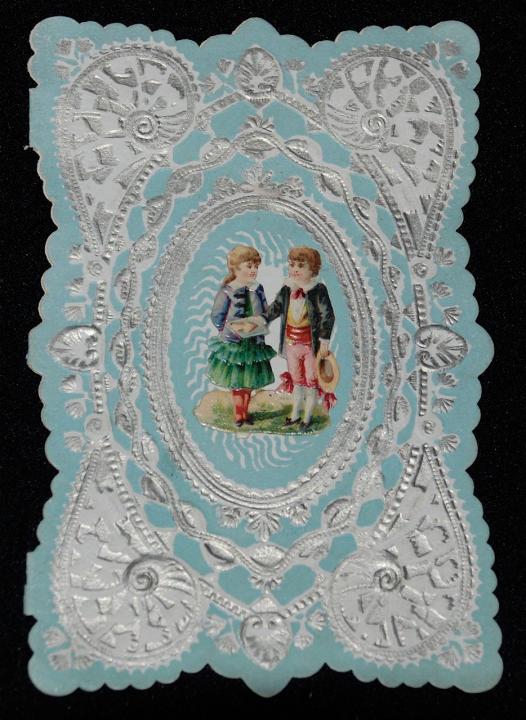

Left: German Valentine’s Day Card, c. 1850. Right: American Valentine’s Day Card. Both images come from Catherine Golden’s essay on Victorian valentines (see below). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

There are some noticeable features connected with the manufacture of valentines. It is not one that requires large factories. Although the numbers made annually must be reckoned by hundreds of thousands, yet—as there is a whole year available for producing that which is wanted for one single day only—small establishments will suffice. There are many such in London, and probably in some of the larger provincial towns. The actual printing, from stone, wood, or type, is the work of men and boys in the usual way; but nearly all else is fabricated by women and children—a light employment, paid for as women’s and children’s work usually is, humbly. The valentines which we have placed in the ‘vulgar’ class are, when printed, handed over to children, who daub them with staring, bright colours, in imitation of a pattern set before them — not always such patterns as young eyes and minds should be called upon to attend to. In the ‘sentimental’ valentines of the last generation, before lace-papers and coloured gelatine-sheets had come into vogue, the process of manufacture was the same in kind but better in quality, the printing being finer, the colours of the ‘loves and doves, hearts and darts’ more care fully managed, and the tender romantic versification written in a ladylike hand instead of being printed. The ‘elegant’ valentines of the present day, however, are far more preten tious affairs, calling for the exercise of some inventive power—not of a high order, it is true, but still some thing a little out of the common. The materials, very varied in character, are procured from diverse sources. Lace-paper, a really beau tiful production, wrought by a combined process of stamping and perforating; lace-cardboard and cards, of similar character; colour-printed sheets of small leaves, twigs, fruit, berries, flowers, birds, butterflies, &c., ready to be cut out by scissors; plain-printed sheets of Cupids, Hymen, angels, fairies, cherubs, altars, flames, hearts, wreaths, and other prettinesses, to be coloured by hand, and then cut out; thin sheets of richly-coloured adhesive gelatine — that beautiful substance brought into use a few years ago; small pieces of satin, silk, and velvet, painted by hand (often by women of taste, whose lot in life is below the level of their accomplishments); small productions in coloured cambric and other material, such as are fabricated by or for artificial flower makers; embossed papers and cards, with or without gold and silver as parts of the embossment; plain tissue-paper and cardboard of various kinds—such are the component elements of the more expensive and elaborate class of valentines.

And then comes the process of putting together. The master (or mistress) of the workshop must be a person of some tact and taste, able to devise new forms and combinations, and to superintend the arrangements for realizing them in the finished valen tine. Scissors and gum are greatly in request. If we follow the example of that famous juvenile hero who made experimental researches on the pneumatic principles of a pair of bellows—or, at any rate, if we spend a few pence on an ‘elegant’ valentine, and analyze it, with a view to discover ‘its mode of production—we shall find that a good deal of ingenious work is bestowed upon these little productions: much more than seems consistent with the small price at which the articles are sold. All is head-work or finger work in these making-up work shops, aided by a few small simple tools: no scope for large machines and apparatus after the sheets have once been printed, stamped, and embossed.

The principal valentine-makers must necessarily have some little capital to fall back upon. During the greater part of the year they are paying for labour and materials to produce articles which are only pur chased by the public for one single day’s use, and by the shopkeepers [180/181] chiefly in the month of January, in good time for the eventful 14th of February. The invested capital need not be large, however, for the costly valentines are few in number, and all the rest are very cheaply produced. The ‘Trade’ have their talk about valentines at three, five, seven, ten, and even a greater number of guineas each; of royalty sending such elegancies to royalty; of a wealthy cit [sic] who was wont some time ago to give to each of his daughters a five guinea valentine every year. These, however, are the ‘Upper Ten Thousand’ of the valentine world, exert ing very little influence on the trade in general; and we may fairly sur mise that secrecy is not sought for nor maintained in regard to the name of the sender of such expensive presents.

[Advertising Valentines with “trade-circulars”]

When the end of the year is approaching, and the shopkeepers are laying plans for new enterprises after the Christmas and Twelfth Night trinkets shall have been all sold, the principal valentine-makers send their trade-circulars to their customers to denote what temptations are in store for the 14th of February. These circulars are curiosities in their way. Each maker has been striving during the year to strike out something new; and in this, as in muslin-printing and many other trades, a new pattern will by a lucky chance prove an immense success, a ‘sensation,’ not at all guessed or anticipated beforehand; while others, regarded as equally hopeful in the first instance, fall dead upon the market. One such success, a year or two ago, was the valentine with a slide, door, curtain, or other little mechanical contrivance, revealing certain amazing secrets when drawn aside—such as Mr. Caudle nursing the baby, while Mrs. C. is comfortably lying between the sheets; or the removal of a false head of hair from a fashionable beau; or the un-crinolining of an old young lady, exhibiting her as a skinny-de-leany; or the opening of a cupboard-door, and bringing to the light of day a policeman or a clandestine lover. The trade-circulars of which we have spoken contain multitudes of such choice bits as the following :—‘ Octavo embossed Comic and Sentimental, sorted.’ ‘ Cupid hovering over the Forget me-Not (bouquet in satin back ground).’ ‘Satirical Alphabet Valentines (of which one specimen is, “S stands for Sneak, the name reads a bitter one; and yet, truth to speak, for you there’s no fitter one”).’ ‘Butterfly Valentines (with printed verse under the wing).’ ‘Slightly Comic (of which one is, “ Oh, name the happy day when I shall call thee mine!” lift up the centre, and there stands the Old Gentleman. NB. This will be sure to take).’ ‘Comic tinted envelope Sell Valentines (packets of “Comforts for Old Maids,” and “Discomforts for Bachelors,” neatly packed up in envelopes, with appropriate mottoes).’ ‘A neat Comic Valentine (the picture poster for Monkeys, Jackasses, Bores, Puppies, Slovens, and other worthless animals).’ ‘The Valentine Blind (“Pray gently lift the window-blind, the lesson there you’ll find”).’ ‘A very neat imitation of a straw hamper, which, when opened, contains two little boys, with words in writing, “I send you a present, to add to your joys, and make life more pleasant, two nice little -——” with label at tached to the cover, “Pledges of affection”).’ ‘ Companion to the above, containing the clothes.’ ‘The Arrow of Love, and Wheel of Fortune (arrow moves round a circle, and points to the fortune of your love).’ ‘Coloured drawings, rather funny, with appropriate written mottoes (such as a picture of a gentleman examining his shirt and exclaiming, “Not a single button on!”).’ ‘Silver-faced Clock Valentines, on which you can move the hands to point out your friend’s sore places.’ ‘Cupid’s Letter-box, gilt and decorated (words outside denoting the tenderness within ; inside there is a touching love—letter, stamped and ready for despatch).’ ' Trifles towards housekeeping (various domestic articles attached to octavo lace-paper: such as a pair of scissors, bellows, a broom, a chopping-board, dust-shovel, &c., with illustrative words).’ ‘Caught at last (effective landscape background, [181/182] with miniature jointed fishing-rod, line, and hook baited with a heart).’ ‘The Glove Valentine (octave lace lift; large satin centre, 'with words written on satin, “My Love, the Glove I send above, I mean not you should wear; but with your aid, my dearest Maid, we’ll join and make a pair”).’ ‘Comic Heraldic Series (such as Coat of Arms for a Donkey, “My Brother dear”). ‘Photo graphic Tom-cat (likeness of your self).’ Such are samples of the satirical and the humorous valentines, according to the measure of strength in those who invent them; of course the merely elegant cannot so easily be described in words. We will not penetrate into the mysteries of trade so far as to ascertain what ratio the retail prices of such articles bear to the wholesale; but it is quite fair to mention that the profit ought to be good, because the shopkeeper never knows how many valentines he may have left upon his hands when the all-important day is past.

Related material

- The Victorian Revolution in Letter Writing

- Valentine’s Day: Love and Derision “By the Bushell”

- Victorian Christmas Cards: an Everyday Work of Art

[You may use the image above without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Hathi Trust Digital Library and Cornell University and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. — George P. Landow]

Bibliography

“A Chat about Valentines.” London Society 5 (1864): 178-83. Hathi Trust Digital Library online version of a copy in the Cornell University Library. Click on image to enlarge it.

Last modified 4 June 2020