he Victorian era saw the development of Christmas traditions and among them of Christmas cards. But what were they exactly? In a period of economic development and industrialization, they came to be much more important for the middle classes than we can imagine. In order to prove their good taste, they would have to follow the subtle etiquette that surrounded them (Rusch). If these little objects were sent from one family to another to celebrate the end of the year, much like contemporary ones, they also played a major role in bringing art to the Victorian homes, and their importance extended way beyond Christmas time. More than simply a sentimental object and a testimony of friendship and love, the visual and textual content of the cards must be taken into account to further understand their meaning to the Victorians. Indeed, the great variety of cards that still exist today testifies to the importance of this object for the Victorians. They were kept for decades in albums or scrapbooks which made it to the present day” (Conan).

Using the Christmas cards we were able to find in British museums, we shall examine the role of those cards in making art more accessible to the wider population. We first look at the general Victorian context which enabled the development of Christmas traditions and notably the industrialization to better understand the production context of the cards, then we will see how those cards were illustrated by looking at the religious influences and the implication of high art in their design, and finally we will see the popular designs that emerged (in opposition to high art) and how Victorians turned the Christmas cards into domestic pieces of art by collecting them.

New Christmas Traditions and major personalities: the impact of the Royal family and Charles Dickens

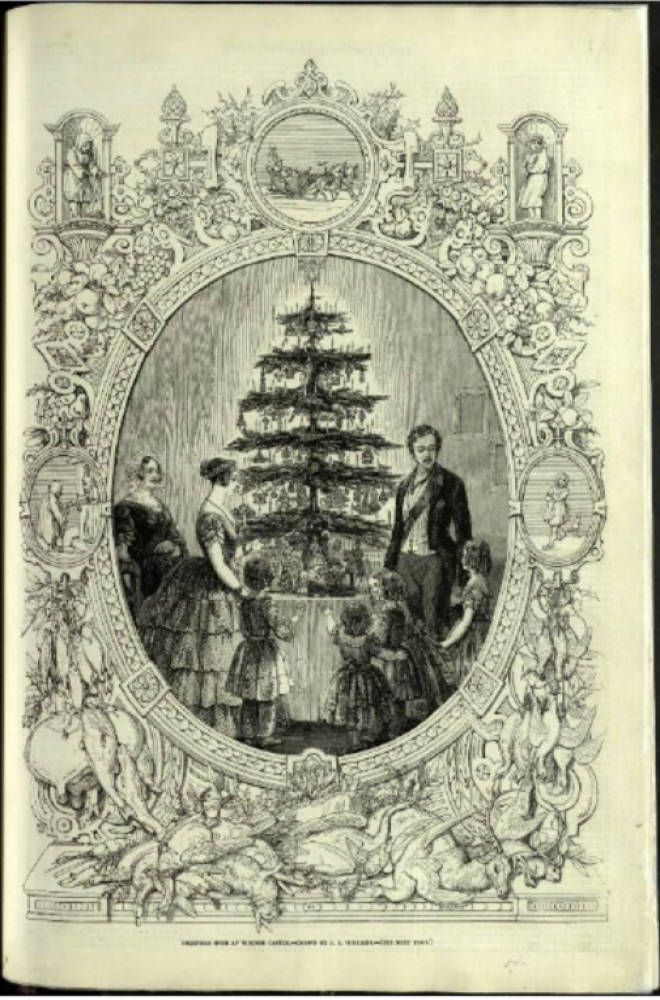

Christmas tree at Windsor Castle from the Christmas supplement to The Illustrated London News (December 1848). Click on images to enlarge them.

In the early nineteenth century, Christmas looked nothing like it does today. “Many businesses didn’t consider it to be a holiday” at all (“Victorian Christmas traditions”), which meant that people had to work, making it hard for them to celebrate with their families. It was not until the 1871 Bank Holidays Act defined public holidays, Before then it was up to the employers whether to give days off or not. Different personalities contributed to add new Christmas trends that are now integral to a British Christmas. We can point to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert who popularised Germanic traditions, when they recreated in Britain the kind of Christmases that they enjoyed as children. According to Kathryn Jones, the assistant curator of decorative arts at the Royal Collection, Prince Albert is associated with popularising the Christmas tree, but the Royal Family had had trees before, since Queen Victoria’s mother was also German. A famous engraving of the Royal Family was published in the Illustrated London News in 1848. It portrayed them celebrating Christmas at Windsor around a decorated Christmas tree, which introduced it to the British. Jones points out that “for most people in Britain the idea of having a tree inside was completely new” (Migley). Local army barracks and schools received decorated Christmas trees sent by the Royal family. The Royal Christmas tree was decorated by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert themselves, prompting British families to do the same and to personalise the decoration. The habit caught onquickly, with the first advertisements for tree ornaments appearing in 1853 (“Victorian Christmas traditions”). The Royal family also gave each other Christmas cards, and Queen Victoria’s children “were encouraged to make their own” (“History of Christmas”).

Charles Dickens also contributed greatly to Christmas imagery. Many of his novels took place at Christmas, most notably A Christmas Carol in December 1843. He also wrote numerous Christmas stories in “his weekly magazine Household Words (20 March, 1850- 28 May, 1859) or its successor All the Year Round” (Alligham, “Dickens ‘the man who invented Christmas’”, The Victorian Web). His Christmas stories contributed to establish the concept of the white Christmas.

Christmas Eve at Mr. Wardle's by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) from the January 1837 "Christmas" number of Dickens's Pickwick Papers. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

According to his biographer Peter Ackroyd, “during the first eight years of his life there was a white Christmas every year” (Alligham, “Dickens ‘the man who invented Christmas’”, The Victorian Web) which had an impact on his perception of Christmas. In Professor Philip Allingham’s words, he “fixed our image of the holiday season as one of wind, ice, and snow without, and smoking bishop, piping hot turkey, and family cheer within.” (Alligham, “Dickens ‘the man who invented Christmas’”, The Victorian Web) These motifs are recurrent on Christmas cards, showing the big impact that he has had.

The development of the Royal Mail and the technical improvements of the Industrial Revolution

In 1840, a reform of the Royal Mail in the UK led to the creation of the Uniform Penny Post by Rowland Hill. This reform reduced the cost of shipping letters, and made it possible for the whole population to send letters at a cheap price. These ideas of safety, speed and cheapness became essential in the democratization and the proliferation of Christmas cards in the UK. The new postal system was a financial disaster as it allowed a larger population to send letters and cards at a cheap price. Though it was later on abandoned, it served a great purpose in facilitating communication in a period of population growth.

Moreover, the introduction of the halfpenny postage rate on postcards in 1870 consolidated the popularity of the Christmas cards. Patrick Joyce argues that “675 million letters were delivered nationally in 1864 and 800 million in 1870; plus, in 1871, 75 million postcards.” (Joyce, The State of Freedom: A Social History of the British State since 1800, 65). Consequently, people could buy cheap Christmas cards in bookshops and stationers and send them cheaply too, with the assurance that they would be received quickly.

It was in this context that the first Christmas card was created. In 1843, Sir Henry Cole, who would become the first director of the Victoria & Albert Museum, commissioned a Christmas card to his friend John Horsley who designed it. This card was sold in his shop in 1846, with a stock of 1,000 copies.

The First Christmas Card designed by John Horsley for the predecessor museum of the V&A.

However, these first cards were really expensive, as they were “printed using a process called lithography. The outlines then had to be hand-coloured by a professional colourer.” (Trainor, Victorian London Slums Seven Dials, 194). As the cards were hand-produced, their cost of production was high. Consequently, not everyone could afford buying one as “they were sold for one shilling each, which incidentally was far more than the daily wage for many Victorian workers at that time” (Trainor, 194).

If the idea of a Christmas card started to emerge thanks to the reform of the postal system and to the commercial genius of Cole, it was the context of the Industrial Revolution that propelled this iconic Victorian object. The Second Industrial Revolution, which started around 1870 and ended around 1914, greatly helped in bringing the Christmas traditions in Victorian homes. Indeed, the changing methods of production led to the creation of new technologies, such as new printing methods which reduced the cost of production and made it possible for a certain number of objects to be mass produced. This meant that the sale price was reduced and that people, notably from the middle class, could now afford those objects as the economic growth of the period improved their living standards “in the form of higher per capita incomes and greater consumer choices.” (Spielvogel, Western Civilization, Volume II: Since 1500, 631).

The Christmas card thus benefited from the technical improvements of the 1860s-1870s with the invention of chromolithography, a much cheaper technique than lithography. The development of the high-speed steam press, associated with the process of chromolithography permitted to produce faster and cheaper prints. Indeed, “chromolithography made printing beautiful color cards inexpensive and fast.” (Anderson, Victorian Advertising of Gloucester, 1). With the advent of this new technique, a large number of publishers started to commercialize Christmas cards, such as Charles Goodall & Son. Originally playing-card manufacturers, they launched a series of Christmas cards in 1862. Others, such as Robert Canton, originally a Valentine cards publisher, started selling a collection of cards in the 1860s.

Many others joined the industry between 1860 and 1880, such as Benjamin Sulman, Dean & Son, Marcus Ward & Co, De La Rue & Co, Eyre & Spottiswoode, Raphael Tuck & Sons, Siegmund Hildesheimer & Co, Hildesheimer & Faulkner, Augustin Thierry, Herman Rothe, Birn Brothers or Thomas Stevens.

Illustrating Christmas cards: religious influences and the coming of high art in a popular medium; or a pagan festival steeped in Christian imagery

Left: The Saviour Lead Thee Thro’ the Year. Right: The Lord Bless Thee and Keep Thee. 1880. From the Brighton Museum Collection of Christmas Cards.

As T.H.S. Escott puts it, “The Victorian age is in fact above all others an age of religious revival.” (Social Transformations of the Victorian Age, 399). Indeed, some historians like Owen Chadwick note that the clergy became more zealous from the middle of the 1850s, they “conducted worship more reverently, knew their people better, understood a little more theology, said more prayers, celebrated sacraments more frequently, studied the Bible, preached shorter sermons” (151).

There were references to Christian imagery in all visual arts and literature, as these were codes that all Victorians would understand regardless of their personal beliefs, since it was so prevalent in society. They would view both poetry and prose through this interpretive filter. There is therefore nothing surprising in seeing Christmas cards featuring Jesus, angels, crosses, sheep as well as full Bible verses or mentions of the Lord and wishing that he will watch over the person receiving the card.

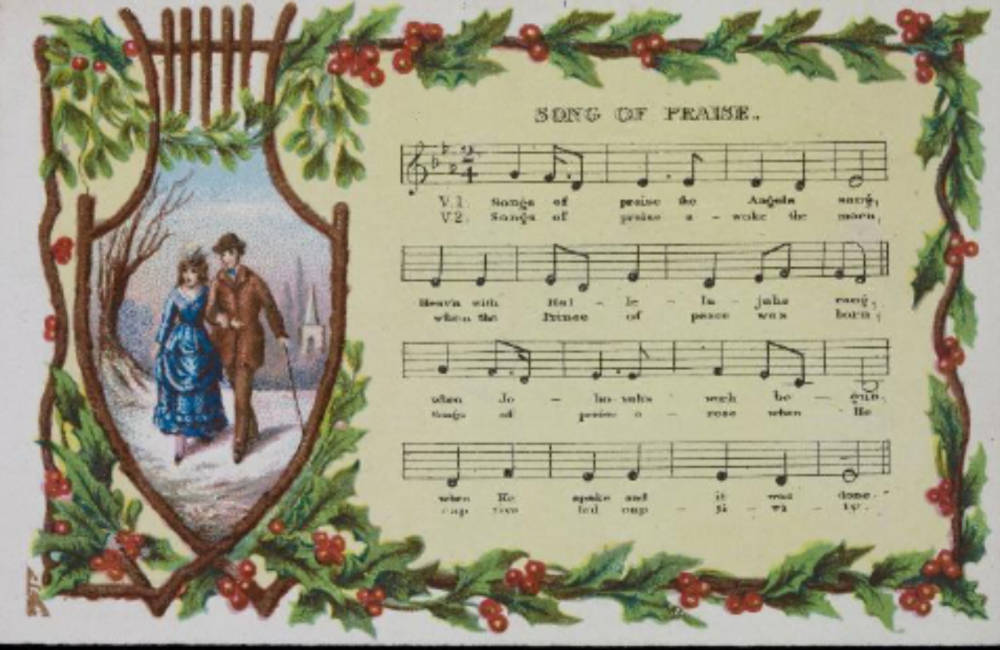

Some Christmas cards also featured carols. They existed before the nineteenth century, but they were “revived and popularised” (Anonymous, “History of Christmas”, BBC) at that time. The most popular carols were “O Come all ye Faithful” (1843), “Once in Royal David’s City” (1851), “See Amid the Winters Snow” (1868) and “Away in a Manger” (1883) (Johnson).

From the Victoria & Albert Museum Christmas card collection. It reads: “Song of Praise. Songs of praise the Angels sang, Heav’n with Hallelujahs rang, when Jehovah’s work begun, when He spoke and it was done. Songs of praise awoke the morn, when the Prince of peace was born; Songs of praise arose when He captive led captivity.

High art and popular culture: the role of Christmas Cards in democratizing art and making it accessible to the wider audience

The Christmas card, in the Victorian era, was already conceived as a combination of words and pictures. As such, it used extracts of literary works, poems and illustrations, sometimes made by well-known painters of the Victorian period. Lorraine Janzen Kooistra thus argues that illustrated gift books “celebrated the association of poems and images, seeing mass production as a means of disseminating the elites arts of poetry and pictures to an audience in need of cultivation. In this respect, the technologies of the age of mechanical reproduction play a crucial role in the story of this artefact, connecting the “high art” of painting and exhibition culture with the mass art of print culture” (2). This definition can very well apply to Christmas cards. Indeed, they played a role in the diffusion of high art among the population. This constitutes the ambivalent status of the Christmas card as an object of popular culture and at the same time as a vehicle of high art, or in the words of Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, as “a product of large scale cultural production that carries with it some of the symbolic value of restricted cultural production.”. As such, Christmas cards can also be viewed as educational tools used for the diffusion of culture. They participated in breaking down the barriers between an elite culture and a popular culture in a period of economic and cultural growth and of deep interest in the arts and crafts that the nation produced. They presented knowledge in an easily accessible way (Williams).

The numerous art magazines of the time took an interest in this growing phenomenon. The Art Journal, the most prominent Victorian magazine of art announced that

MARCUS WARD & CO., of Belfast and London, have issued their season collection of Christmas cards. They are such as justify their claim to lead in this class of Art work, good in design, and excellent in execution, and fully sustaining the firm in the high position they occupy among producers of illustrated publications. (“Minor Topics”).

This meant that the beauty of the cards was worth speaking of in a major art magazine and that the cards came to be recognized as pieces of art. The same way, the editor of the art magazine The Studio, Gleeson White, underlined the “‘courageous attempt’ on the part of the designers and the publishers of the cards to bridge the ‘great division which separates so many of the applied arts of commerce, and the higher art” (Zakreski). Sara M. Dodd adds that “the gap between “high art” and “popular design” was closing. Royal Academicians were sometimes brought in by publishers to raise the status of Christmas cards” (48). Indeed, many publishers requested Christmas cards to be signed by Royal Academicians and fine artists, such as Walter Crane, William Coleman, Rebecca Coleman, or Henry Stacy Marks, John Callcott Horsley, Herbert Dicksee and William Frederick Yeames (Zakreski). Raphael Tuck & Sons even launched a “Royal Academy series” in 1882 (Zakreski). Some artists launched their career by designing Christmas cards before becoming famous in the profession, such as Kate Greenaway who became a member of the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours in 1889.

Christmas greeting card by Kate Greenaway circa 1880, Chromolithograph, Marcus Ward & Co.

This shows that this popular industry was a pool of fine artists and not amateurs. We can say that with the development of Christmas cards, high art left the galleries and exhibition walls to enter the homes of middle-class Victorians. The great circulation of cards made possible thanks to the reform of the postal system and to mass production led to little pieces of art being disseminated in many households throughout the Empire. The Reliquary, an archaeological journal, stated in 1881: “Christmas Cards are decidedly to the fore as art educators of the people [. . .] [T]hey bring high art—really high art—along with loving words and friendly wishes to the poorest cottages, and thus, while pleasing the eye and educating the mind, cheer and warm the heart, raise the spirits, and help to bring joy and happiness to the home” (quoted by Zakreski)

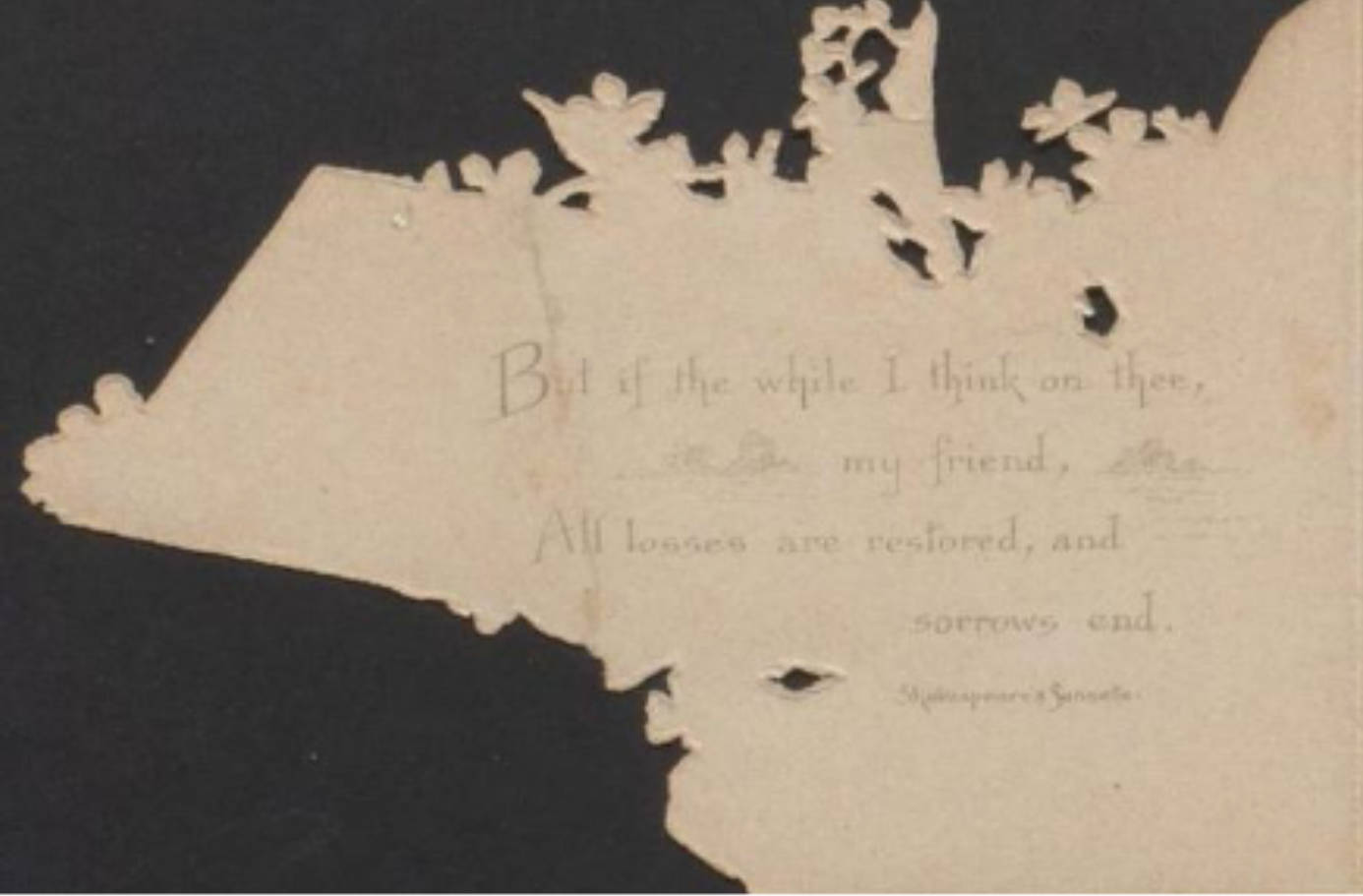

More than just wishing a happy new year and a merry Christmas, the textual elements of the cards also comprised references to the high art of poetry. It is interesting to see that people associated short verses with their personal messages. They combined the two as if they had appropriated the poems, sometimes not even mentioning the name of the poet. It added a layer of refinement to the card. The verses and the illustration chosen were thus a way of showing the taste of the person who sent the card.

Moreover, the poems and phrases written on the cards testified to the existence of a shared culture among the middle-classes. They would write references to Dickens’s novels, to eighteenth-century poets like Robert Burns or to traditional hymns like “Good Tidings of Great Joy” or “Peace on Earth”. Christmas cards thus became a seasonal celebration of the British culture. They highlighted both the textual and visual savoir-faire of the nation, through the references to well-known poets and the participation of fine artists in the creation of those cards. Fine art could finally be enjoyed and shared by the masses and not solely by an elite.

This Christmas card contains verses from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 30: “But if the while I think on thee, dear friend, All losses are restor'd and sorrows end.

Popular designs in Christmas cards and the creation of middle-class “home galleries.” or how to keep a little bit of art at home.

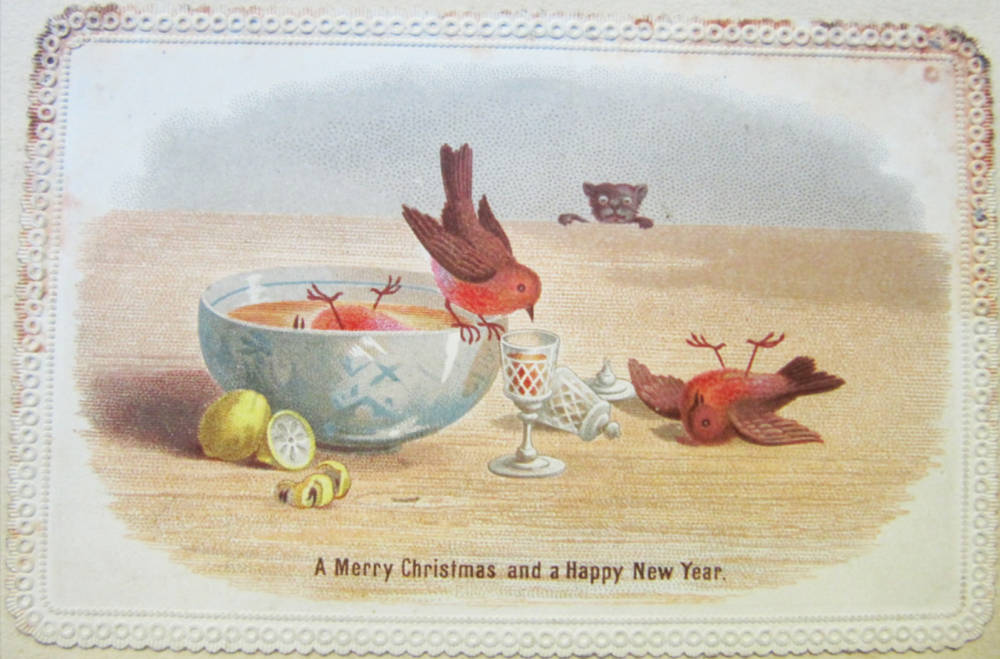

A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. c. 1876. NLI Ref.: Arthur Conan's Xmas Scrapbook, 4188 TX (2). The library site comments, “These robins have been imbibing the Christmas Spirit a little too freely, and the cat in the background looks as if all his Christmases have come at once...”

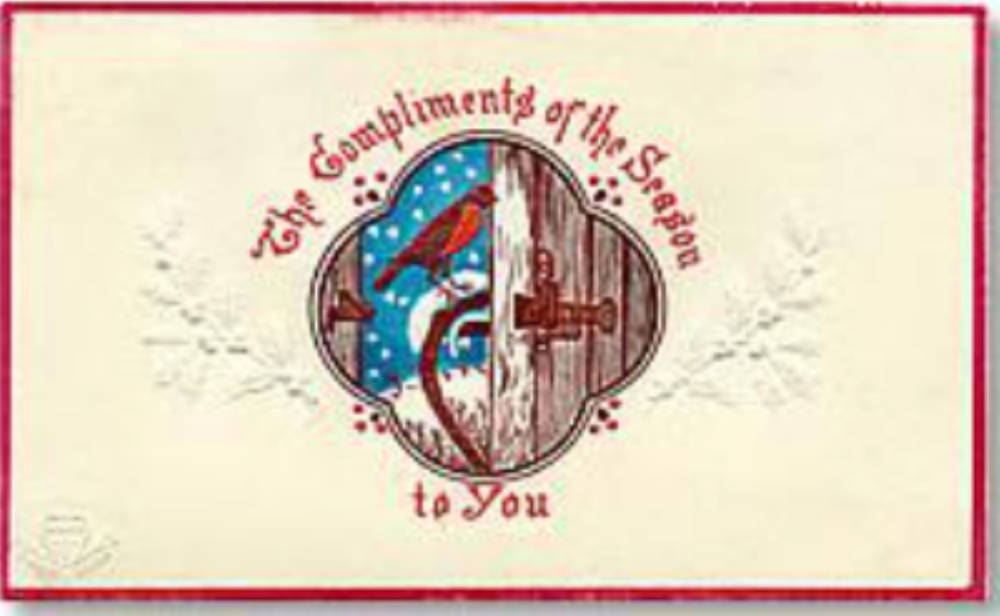

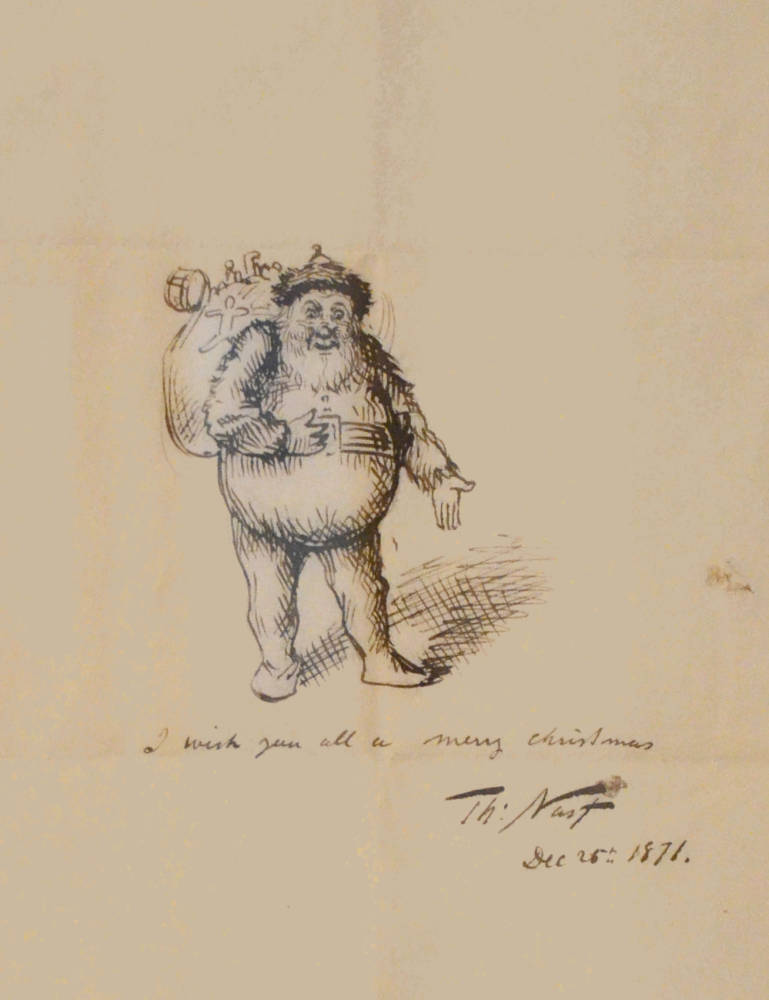

As we saw earlier, Christmas cards could focus on aesthetics rather than depicting seasonal elements. Fine arts motifs were frequent, showing animals, flowers and foliage along with seasonal greetings. These cards would not be easily identified as Christmas cards in today’s eyes if it were not for the seasonal greetings. Flowers often appeared, not only for their aesthetic qualities, but also because Victorians were fond of floriography and collecting flowers in scrapbooks. Pets appeared often, they were a reminder of the family home, especially dogs who were symbols of loyalty. Birds were also depicted; alive or dead. They might reference people who are not fortunate enough to celebrate Christmas and die in the cold. Dead robins could also be a reference to the Irish good-luck ritual which took place on December 26 called “Wren Day”. The “political cartoonist Thomas Nast” (Baghsaw) was the first one to represent Santa Claus in a way that we would recognize in Harpers Weekly in 1881, which became a recurring character with variations on Christmas cards. Other imagery included “seascapes, snowless landscapes”, “smoking and writing utensils” (Baghsaw) as well as more conventional seasonal motifs.

Two by the great American political cartoonist and book illustrator, Thomas Nast: Left: Merry Old Santa Claus. Harper's Weekly (1 January 1881): 8-9. Right: I wish you all a Merry Christmas. 1871. From pr1vate collection. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

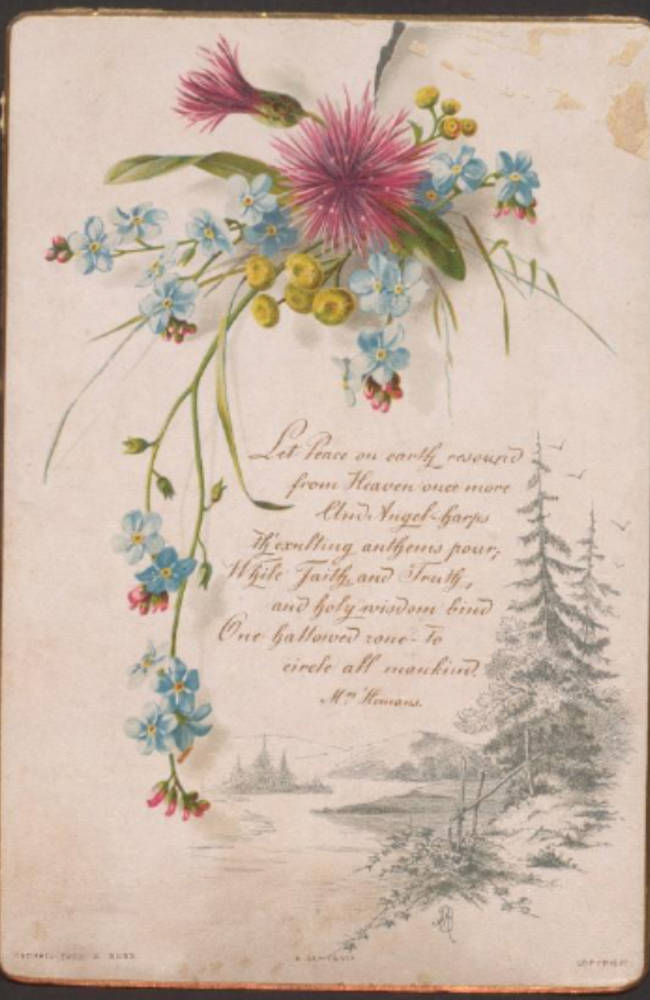

Some cards also featured original poetry, with some authors specialising in Christmas verses, like Helen Marion Burnside (1841-1923). She was a “prolific writer of songs, poems, tales, and card verses” (Reilly, 73). Rather known poets whose verses featured on Christmas cards include: Eliza Cook, Frances Ridley Havergal, the poet and farmer Robert Burns, who wrote poems that “celebrated aspects of farm life, regional experience, traditional culture, class culture and distinctions, and religious practice and belief” (Brown, “Robert Burns”, Poetry Foundation); the Romantic poet Felicia Hemans and the Irish writer Samuel K. Cowan. More obscure poets include Charlotte Murray, E.E. Griffin, Frederick Lanbridge and M.R. Jarvis. Christmas verses tended to be quite short, which made them easy to memorise, and carried positive words like “love”, “peace” and “wisdom” as well as religious sentiment with words like “Heaven”, “Angel”, “Faith” and “holy” (see examples below). They tended to follow familiar rhyme patterns as well, putting them somewhat on equal footing with other types of poems like H.M Burnside’s enclosed rhyme or Felicia Hemans’s couplet quatrain (see below).

Tow examples from the Brighton Museum collection of Christmas cards. The one at left features a poem by H.M. Burnside, whicch reads, “Christmas. Tis but a tiny fragile spray/ Reft from the wealth of summers prime, Which thus through winters frost and rime, Bears you my love on Christmas Day”. The one at right reads: “Let Peace on earth resound from Heaven once more/ And Angel harps exulting anthems pour; While Faith and Truth and holy wisdom bind/ One hallowed zone to circle all mankind.”

Collecting and displaying Christmas Cards: a Victorian habit

The great diversity of cards and designs as well as their quality makes us understand why so many of them still exist today in large collections in a variety of museums such as the Brighton Museum or the Victoria & Albert Museum. A Christmas card was a precious object for the Victorians, both because it carried with it personal and sentimental messages, and because it served as an aesthetic object that could be displayed in the house or kept in albums. Christmas cards were kept because of their social and artistic dimensions. They were “gifts to be presented and then displayed: aesthetic objects combining instruction, entertainment, decoration, cultivation, and conspicuous consumption” (Janzen, , 2).

Christmas cards thus became a huge part of the collecting mania of the Victorian era. According to Jacqueline Yallop.

In 1856, Henry Cole came to the conclusion that “the taste for collecting” was now “almost universal”, and, by the end of the 1860s, The Graphic, an illustrated political journal, was able to go a step further by claiming that “this is the collecting age”. From enthusiastic shoppers to expert connoisseurs, the collecting habit was becoming entrenched in the homes of the Victorian middle classes. (33)

From a scrap album.

As we know that Victorians were fond of collecting any type of objects, the process of collecting and keeping Christmas cards is easily understandable. Their sizes, usually not exceeding the size of a postcard, made them easy to display and to collect. Moreover, many of the cards did not represent the traditional Christmas images we know today but instead focused on images of the countryside or of flowers and thus evoked the coming of spring. Christmas cards could therefore be reused independently of the season, which extended their use beyond Christmas time. Some of them were even made to be displayed on a chest of drawers for instance as they “stand up and may have several layers or depths to create a truly dimensional effect” (Pegler, 371).

Large collections of Christmas cards were thus created thanks to scrapbooks and albums during the Victorian era, which permitted people to look at the different pieces of art they had gathered over time. They could share their collection with their family and their friends through the year. Consequently, we can say that the power of the Victorian Christmas cards resided in their status as everyday works of art.

Christmas Card c. 1880.

Even though midwinter festivals had been celebrated in Britain for a long time (Johnson), it is during the Victorian period that it grew into the well-loved festival that we know today. The humble Christmas card reflected these cultural shifts, incorporating popular art, high art and both religious and pagan imagery. It embodied a society torn between industrial progress that allowed cheap art to be mass produced and the wish to make aesthetically refined, moral art. It also drew upon other practises common at the time, like scrapbooking or the overwhelming death representations that seem quite bizarre to us today. As Linda Peterson points out, “competing discourses operated within Victorian culture, [and] the language and thought of religion jostled with secular ways of knowing and being in the world” (149). As the Christmas card is such a humble object, efforts to study it and keep its meaning alive have been slight. However, they have crystallised the different interests of their time and testify to the spirit of an age that we may have lost. Hopefully the new additions of family collections to museums might rekindle an interest in this subject, since they were so meaningful to people at the time, and very little research have been done on the subject.

Related material

- A Victorian History of Valentine’s Day Cards

- (Review of) Neil Armstrong's Christmas in Nineteenth-Century England

Bibliography of Print Material

Anderson, Kenneth. Victorian Advertising of Gloucester. Gloucester: Kenneth Anderson, 2008.

Anonymous. “Minor Topics.” The Art Journal. 18 n.s. (1879)London: George Virtue, .

Arnstein Walter, Bright Michael, Peterson Linda. and Temperly, Nicholas. “Recent Studies in Victorian Religion”. Victorian Studies, Vol. 33 no1. Indiana: Indiana University Press, Autumn 1989.

Chadwick, Owen. The Church of England, Vol 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966.

Dodd, Sara. “Conspicuous Consumption and Festive Follies: Victorian Images of Christmas.” Christmas, Ideology and Popular Culture. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008.

Escott, T.H.S. Social Transformations of the Victorian Age. London: Seeley, 1897.

Janzen, Kooistra, Lorraine. Poetry, Pictures, and Popular Publishing: The Illustrated Gift Book and Victorian Visual Culture, 1855-1875. Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2014.

Joyce, Patrick. The State of Freedom: A Social History of the British State since 1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Pegler, Martin. Visual Merchandising and Display. 5th Edition, Bloomsbury Academic: Fairchild Books, 2006.

Reilly, Catherine. Mid-Victorian Poetry, 1860-1879. London and New York: Mansell Publishing Limited, 2000.

Spielvogel, Jackson. Western Civilization: Volume II: Since 1500. Wadsworth: Cengage Learning, 2011.

Trainor, Terry. Victorian London Slums Seven Dials. (s.l): Terry Trainor, 2012.

Yallop, Jacqueline. Magpies, Squirrels and Thieves: How the Victorians Collected the World. Great Britain: Atlantic Books Ltd, 2011.

Zakreski, Patricia. “The Victorian Christmas Card as Aesthetic Object: 'Very interesting ephemer' of a very interesting period in English Art-production'”. Journal of Design History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, November 2015.

Articles on the World Wide Web

Allingham, Philip. “Dickens ‘the man who invented Christmas’” The Victorian Web, 14 Dec. 2009, http://www.victorianweb.org. Accessed 14 Apr. 2019.

Anonymous. “History of Christmas”. BBC, 2014. Accessed 14 April 2019.

Anonymous. “Victorian Christmas traditions”. Victoria & Albert Museum, Dec. 2016. Accessed 15 April 2019.

Anonymous. “Uniform penny postage.” The Postal Museum, n.d. Accessed 14 April 2019.

Baghsaw, Marcus. “Origins of the Victorian Christmas card”. Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove, 23, Nov. 2018. Accessed 14 April 2019.

Brown, Mary Ellen. “Robert Burns”. Poetry Foundation, 2019, Accessed 8 April 2019.

Conan, Arthur. “Xmas Scrapbook, 4188 TX (2)”. National Library of Ireland, Circa 1876, Image obtained from Flickr. Accessed 10 Apri; 2019.

Johnson, Ben. “A Victorian Christmas.” Historic UK., n.d.. Accessed 14 April 2019.

Midgley, Emma. “Queen Victoria popularised our Christmas traditions”. BBC, 15 December 2010. Accessed 14 April 2019.

Rusch, Barbara. “The Secret Life of Victorian Cards”. The Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America, n.d., Abaa.org. Accessed on 27, Sep. 2019.

Williams, Raymond. “On High and Popular Culture.” The New Republic (22 November 1974). Accessed 15 April 2019.

Created 14 Apri 2019

Last modified 21 November 2021