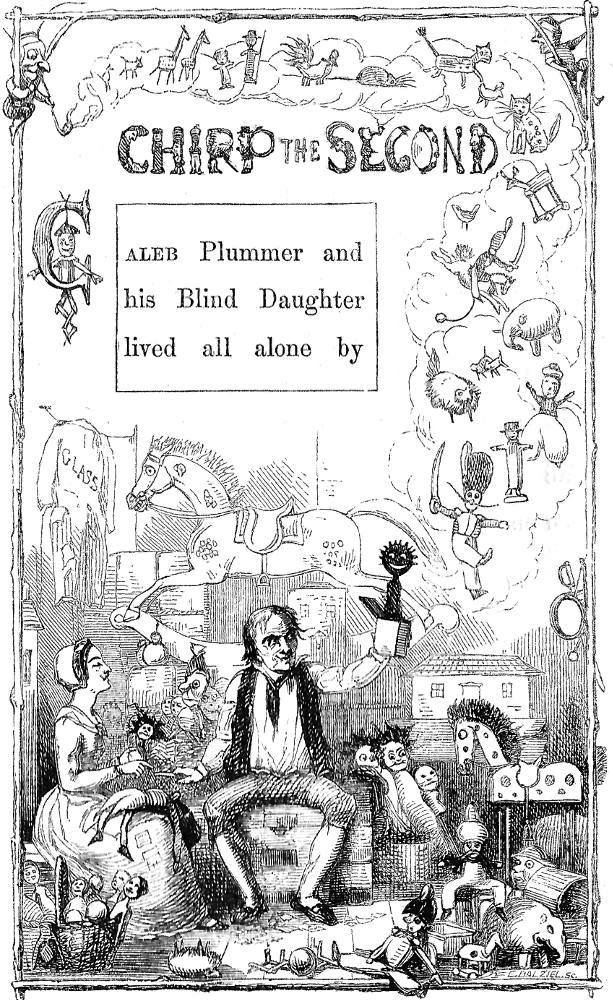

Chirp the Second

Richard Doyle; engraver, Edward Dalziel

1845

Wood engraving

11.5 cm high by 6.7 cm wide (4 ½ by 2 ⅝ inches), framed

Full-page illustration with integrated text for Dickens's The Cricket on the Hearth, "Chirp the Second," 54.

Text enclosed: Caleb Plummer and his Blind Daughter lived all alone by. . . .

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. ]

Passage Illustrated: The Toymakers' Cottage

Caleb and his daughter were at work together in their usual working-room, which served them for their ordinary living-room as well; and a strange place it was. There were houses in it, finished and unfinished, for Dolls of all stations in life. Suburban tenements for Dolls of moderate means; kitchens and single apartments for Dolls of the lower classes; capital town residences for Dolls of high estate. Some of these establishments were already furnished according to estimate, with a view to the convenience of Dolls of limited income; others could be fitted on the most expensive scale, at a moment's notice, from whole shelves of chairs and tables, sofas, bedsteads, and upholstery. The nobility and gentry and public in general, for whose accommodation these tenements were designed, lay here and there, in baskets, staring straight up at the ceiling; but in denoting their degrees in society, and confining them to their respective stations (which experience shows to be lamentably difficult in real life), the makers of these Dolls had far improved on Nature, who is often froward and perverse; for they, not resting on such arbitrary marks as satin, cotton print, and bits of rag, had superadded striking personal differences which allowed of no mistake. Thus, the Doll-lady of distinction had wax limbs of perfect symmetry; but only she and her compeers. The next grade in the social scale being made of leather, and the next of coarse linen stuff. As to the common people, they had just so many matches out of tinder-boxes for their arms and legs, and there they were — established in their sphere at once, beyond the possibility of getting out of it.

There were various other samples of his handicraft besides Dolls in Caleb Plummer's room. There were Noah's arks, in which the Birds and Beasts were an uncommonly tight fit, I assure you; though they could be crammed in, anyhow, at the roof, and rattled and shaken into the smallest compass. ["Chirp the Second," pp. 57-58]

Commentary: Comic Relief, Fanciful Toys, and Social Commentary

Since John Peerbingle and family constitute a middle-class domestic menage, throughout "Chirp the First" Dickens's vision of the carrier's family, ably supported by the fireside scenes of Leech and Doyle in particular, constitute a marital and familial idyll. Not so the scenes involving toymaker Caleb Plummer and his blind daughter, Bertha, who constitute the exploited proletariate, despite the picturesque nature of their workshop. For them there is no distinction between private life and work, but Caleb puts a good face on their economic plight. In other words, in the first two "Chirps" Dickens presents two worlds, that of the comfortable middle-class and that of the disadvantaged under-class. "A point of this [second] chapter is for the reader to see what is happening in the dual world — ordered and chaotic — of the Plummers. Few chapters in all of Dickens's works are so insistently preoccupied with words relating to sight as the opening of Chirp 2" (Patten, 181). And the key to readers' seeing the Plummers' external reality (not the sugared version Caleb gives his blind daughter) is the three illustrations of the toymakers at work, the second being John Leech's Caleb at Work on page 61. Caleb in these plates delights in his creations which surround him. "Moreover, the reader sees what Caleb sees, in three illustrations, one by Richard Doyle and two by Leech" (Patten, 181), the third being Mrs. Felding's Lecture on page 103.

They depict the same room and in the first two images the same occupants, but are not the same. One might say that Dickens was simply careless about these three illustrations, though that would be at variance with his customary practice. Or perhaps the variations in interpretation of the room and figures bespeak how differently each of us "sees" what is before us, and how that vision is screened and interpreted through filters from past experience. The first version, by Doyle . . . , has Bertha sitting on a stool wearing a cap over her hair, holding dolls on her lap, while Caleb, with rather a frightening face, displays a jack-in-the-box which, obviously, his daughter cannot see. [Patten, 181]

Doyle here brings to life in vivid and myriad detail the toymaker's shop, and the dynamic, middle-aged widower and adolescent daughter. Everything emanates from the hands and head of the ill-kempt Caleb, who takes far more care over his creations than he does of himself, and Doyle depicts the shop in most admired disorder, with the upper right register showing toy animals (presumably for the ark) and several soldiers that Caleb is (presumably) thinking of creating at this moment. To the left, hanging on the clothesline, is the (supposedly) marvellous topcoat actually made of packing cloth labelled "glass." Thus, the illustration represents both Caleb's fancy and the Plummers' chaotic reality.

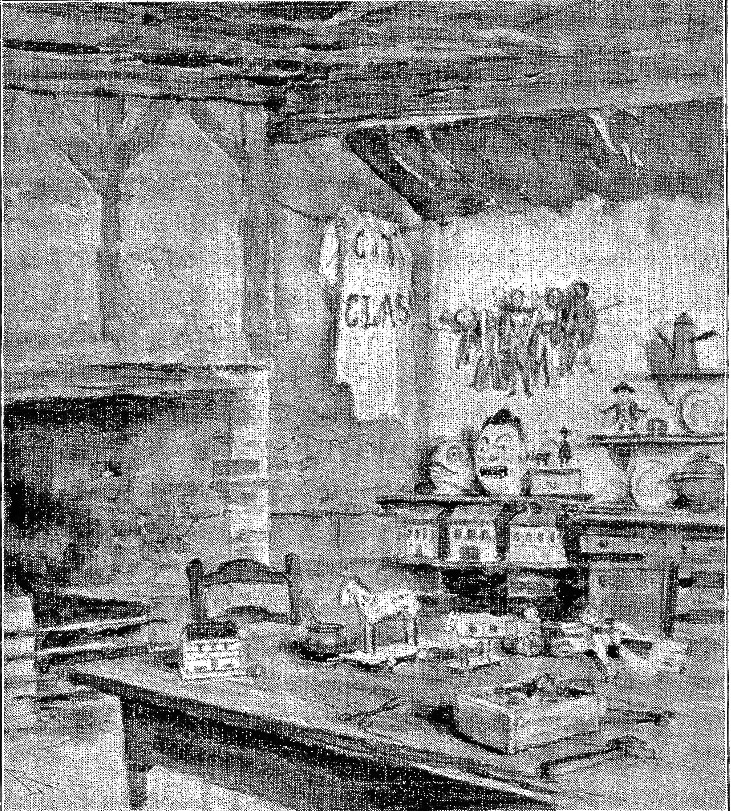

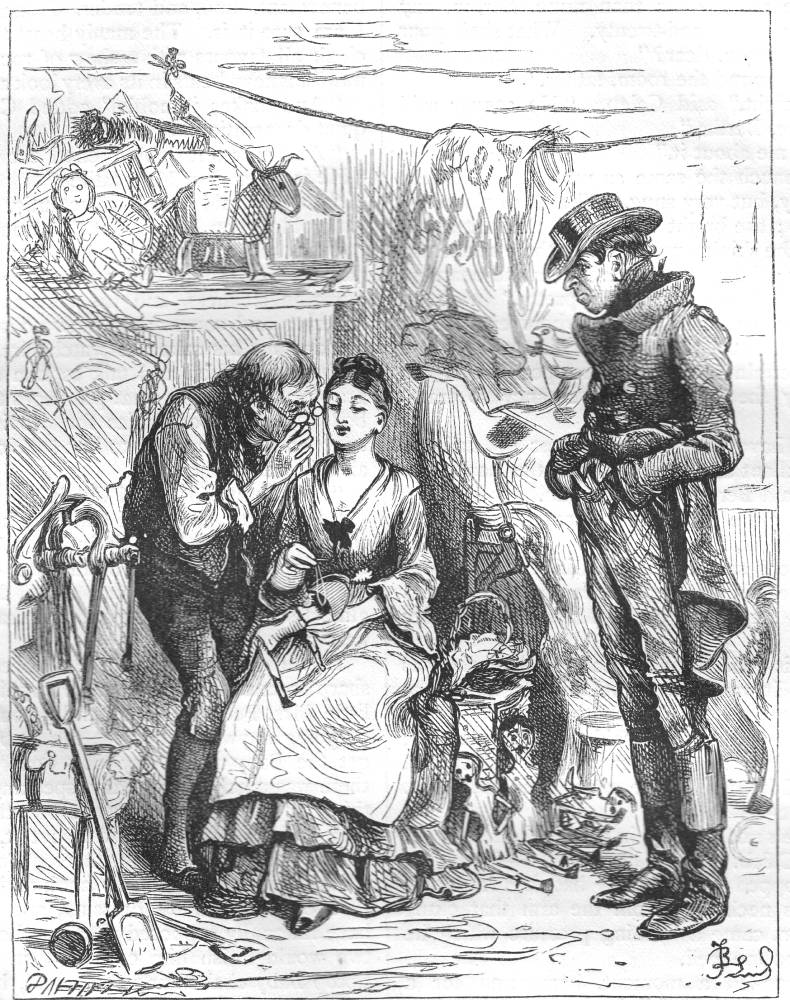

Relevant illustrations from the 1845 and Later Editions

Left: John Leech's surprisingly realistic rendition of the careworn Caleb Plummer, unshaven and bleary-eyed, in Caleb at Work (1845). Centre: Luigi Rossi's realisation of the toymakers' workroom without Caleb and Bertha, Caleb Plummer's Working Room (1912). Right: Fred Barnard's realisation of Caleb and Bertha Plummer in their cottage parlour-cum-workroom, Caleb, Bertha, and Tackleton (1878): for these cottage-industry members of the proletariate there is no distinction between "labour" and "leisure."

E. A. Abbey's realistic study of Bertha and her father at work on a dolls' house, "Halloo! Halloo! said Caleb. "I shall be vain presently!" (1876).

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Cricket on the Hearth. A Fairy Tale of Home. Illustrated by John Leech, Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Edward Landseer. Engraved by George Dalziel, Edward Dalziel, T. Williams, Thompson, Graves, and Swain. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846 [December 1845].

Patten, Robert L. Chapter 8, "Chirping." Dickens, Death, and Christmas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023. 169-199. [Review]

Victorian

Web

Illus-

tration

Richard

Doyle

Cricket on

the Hearth

Next

Created 20 February 2001

Last updated 29 May 2024