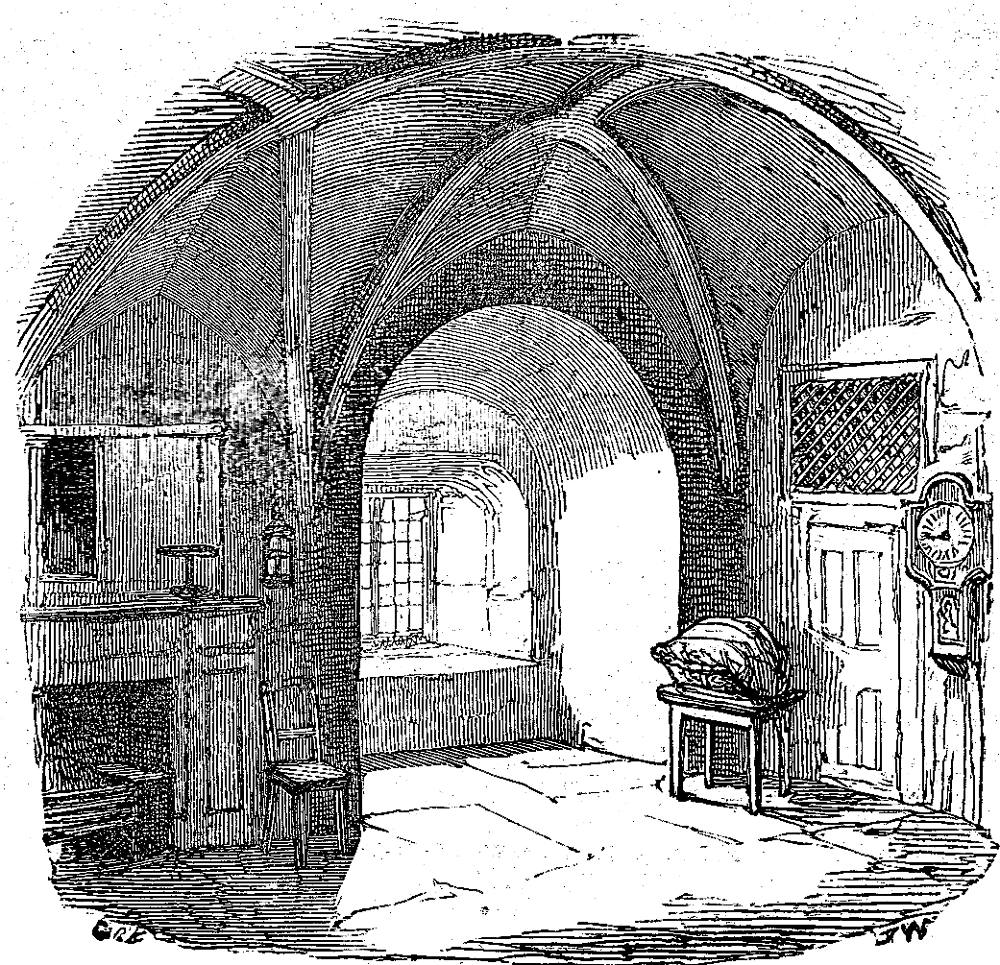

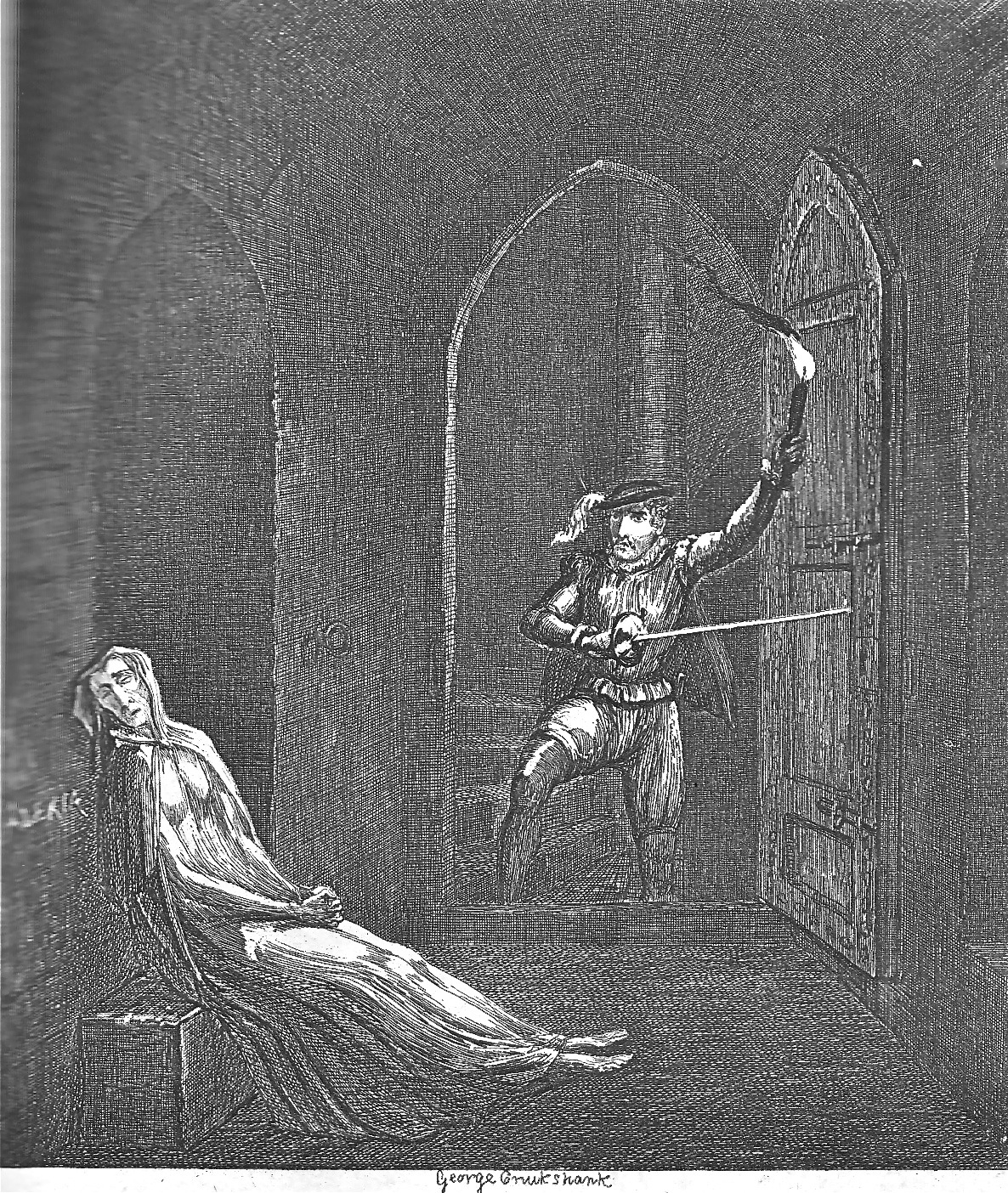

Dungeon Beneath the Devlin Tower. — George Cruikshank. June 1840 number. Forty-second illustration and twenty-fourth wood-engraving in the sixth (June 1840) instalment of William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. A Historical Romance. Illustration for Book the Second, Chapter XI. 6.7 cm high x 9.2 wide, vignetted, middle of p. 191. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Complemented

Having, at Xit's suggestion, armed himself with a torch and materials to light it, and girded on a sword which he found reared against the wall, the esquire followed his dwarfish companion down a winding stone staircase, and speedily issued from the postern.

The night was profoundly dark, and they were therefore unobserved by the sentinels on the summit of the Byward Tower, and on the western ramparts. Without delaying a moment, Cholmondeley hurried towards the Devilin Tower. Xit accompanied him, and after some little search they found the secret door, and by a singular chance Cholmondeley, on the first application, discovered the right key. He then bade farewell to the friendly dwarf, who declined attending him further, and entering the passage, and locking the door withinside, struck a light and set fire to the torch.

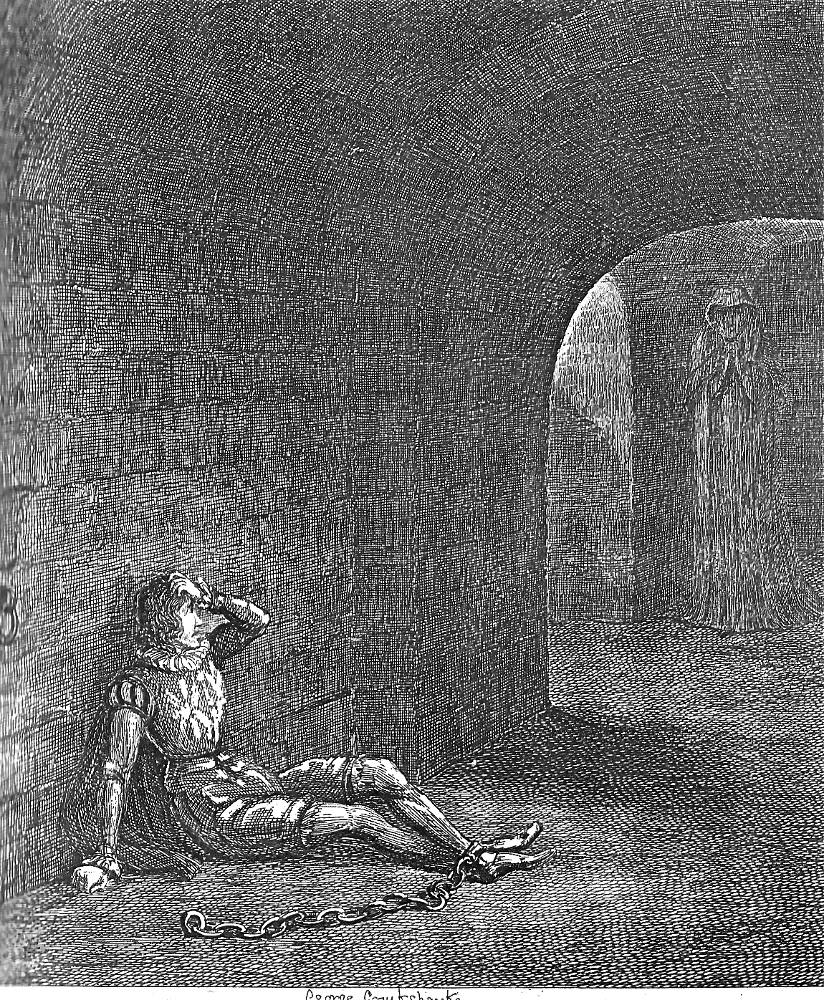

Scarcely knowing whither to shape his course, and fully aware of the extent of the dungeons he should have to explore, Cholmondeley resolved to leave no cell unvisited, until he discovered the object of his search. For some time, he proceeded along a narrow arched passage, which brought him to a stone staircase, and descending it, his further progress was stopped by an iron door. Unlocking it, he entered another passage, on the right of which was a range of low cells, all of which he examined, but they were untenanted, except one, in which he found a man whom he recognized as one of the Duke of Northumberland's followers. He did not, however, dare to liberate him, but with a few words of commiseration passed on.

Turning off on the left, he proceeded for some distance, until being convinced by the hollow sound of the floor that there were vaults beneath, he held his torch downwards, and presently discovered an iron ring in one of the stones. Raising it, he beheld a flight of steps, and descending them, found himself in a lower passage about two feet wide, and apparently of considerable length. Hastily tracking it, he gradually descended until he came to a level, where both the floor and ceiling were damp and humid. His torch now began to burn feebly, and threw a ghastly light upon the slimy walls and dripping roof. [Chapter XI. — "How Cuthbert Cholmondeley Revisited the Stone Kitchen; and How He Went in Search of Cicely," p. 189]

Commentary

We now move from the Beauchamp Tower in the middle of the western side, but to which tower? Ainsworth asserts that another name for the Devlin Tower, located at the extreme eastern of Tower Wharf, is the "Deveraux" Tower, which in fact is a different edifice located near the Beauchamp and By-ward Towers. Whereas the Devlin was built during the reign of King Edward I, in 1282, the Deveraux was built earlier, during the reign of King Henry III (1238-1272), and is much closer to the action that precedes Cholmondeley's going in search of the heroine in the maze of tunnels and cells underneath the Devlin Tower. (How he knows that this is where he should prosecute his search and thereby violate the terms of his incarceration agreement remains unclear.) This tower would be one of the logical places for the Nightgall to incarcerate Alexia and Cicely in the novel since "The tower consists of two stories, with an apartment in each, joined by a spiral stone staircase. Secret passages once ran from the Devereux Tower to the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula and the Beauchamp Tower" ("The Devereux Tower," English Monarchs).

The gothic romance plot now follows Cholmondeley, who is determined to find Cicely, whom he is certain Nightgall has abducted from Sion House and imprisoned somewhere in the Tower. Having stolen Nightgall's keys, the shifty dwarf, Xit, presents them to Cholmondeley so that he can free Cicely, Mistress Potentia's adopted daughter — if he can locate her in the maze of passageways and chambers under the Devlin Tower. Xit and the young esquire leave the precincts of the Stone Kitchen, setting for the novel's comic relief, in order to search for Cicely. After all those well-appointed towers suitable for lodgingprisoners of state such as the Dudleys and Lady Jane Grey, Ainsworth returns readers to a more lurid and Gothic aspect of the Tower of London, the torture chambers, oubliettes, and dungeons which he introduced in the February 1840 number when Nightgall assaulted and abducted Cholmondeley. These, however, the authorities used for the torture of prisoners only insofar as it would serve the purposes of interrogation, so that Nightgall's abuse of power, using the dungeons to pursue his perverted designs, is a little farfetched. With an antiquarian aside, Ainsworth justifies his use of the Devereaux Tower as the site of Cholmondeley's next adventure:

Of a style of architecture of earlier date than the Beauchamp Tower, the Devilin, or, as it is now termed, the Devereux Tower, from the circumstance of Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, the favourite of Queen Elizabeth, having been confined within it in 1601, has undergone less alteration than most of the other fortifications, and except in the modernising of the windows, retains much of its original character. In the dungeon into which Cholmondeley had penetrated, several curious spear-heads of great antiquity, and a gigantic thigh-bone, have been recently found. [p. 191, immediately beneath the illustration, which, since it shows a cell with a window, can hardly be the pit in which rats are devouring the prisoner.]

Ainsworth seems to have deliberately conflated the north-westerly Devereux and the south-easterly Devlin Tower, the tower furthest removed from the western fortifications at the eastern end of Tower Wharf, in order to stage manage a horrific scene in which Cholmondeley saves another of Northumberland's adherents. When the young esquire opens a trapdoor and descends to the lowest level, he discovers the poor fellow, nakedand up to his knees in moat-water. Cholmondeley rescues the prisoner from the Thames water-rats, and sees to his comfort in an upper cell before returning to his search for Cicely. Like the mysterious Alexia, whom Cholmondeley met while imprisoned in Book One, and Cicely, the sufferer has been imprisoned by the malignant jailor.

Illustrations of the Devlin Tower's Dungeons

Left: The wood-engraving of the dungeons that artist and author visited in 1840, Interior of the Devlin Tower — Basement (June 1840). Centre: Cruikshank's fanciful use of the Devlin dungeons in Cholmondeley discovering the body of Alexia in the Devlin Tower (June 1840). Right: The initial appearance of the gloomy regions beneath the Devlin Tower, Cuthbert Cholmondeley surprised by a mysterious figure in the dungeon adjoining the Devilin Tower (February 1840). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The wood-engravings are a record of what Ainsworth and Cruikshank saw on their monthly perambulations of the Tower of London; they do not contribute anything to the atmosphere of Gothic romance, but serve as reminders of what the buildings have become in the nineteenth century — lumber-rooms with no trace of their significance in the history of the English nation. In the case of these dungeons or lower-storey rooms in the Devlin Tower, the large windows seem quite counter to Ainsworth's descriptions of dank, gloomy, ill-lit passages and cells. The somewhat prosaic wood-engravings, however, possess a singular virtue: they enable the serial readers of 1840 to visit these precise locations, to imagine Ainsworth's action unfolding in these rooms, and to put themselves in the positions of Lawrence Nightgall, Cicely, and Cholmondeley in the world of romance, and of Lady Jane Grey, the Princess Elizabeth, Mary Tudor, and Simon Renard in the parallel historical plot. The arches and doorways are real, but the figures and situations from the novel readers visiting the Tower and studying the wood-engravings of 1840 must construct for themselves.

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. 11 September 2017.

Department of Environment, Great Britain. The Tower of London. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967, rpt. 1971.

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

"The Devereux Tower." English Monarchs, http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/tower_london_18.html.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Pitkin Pictorials. Prisoners in the Tower. Caterham & Crawley: Garrod and Lofthouse International, 1972.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 17 October 2017