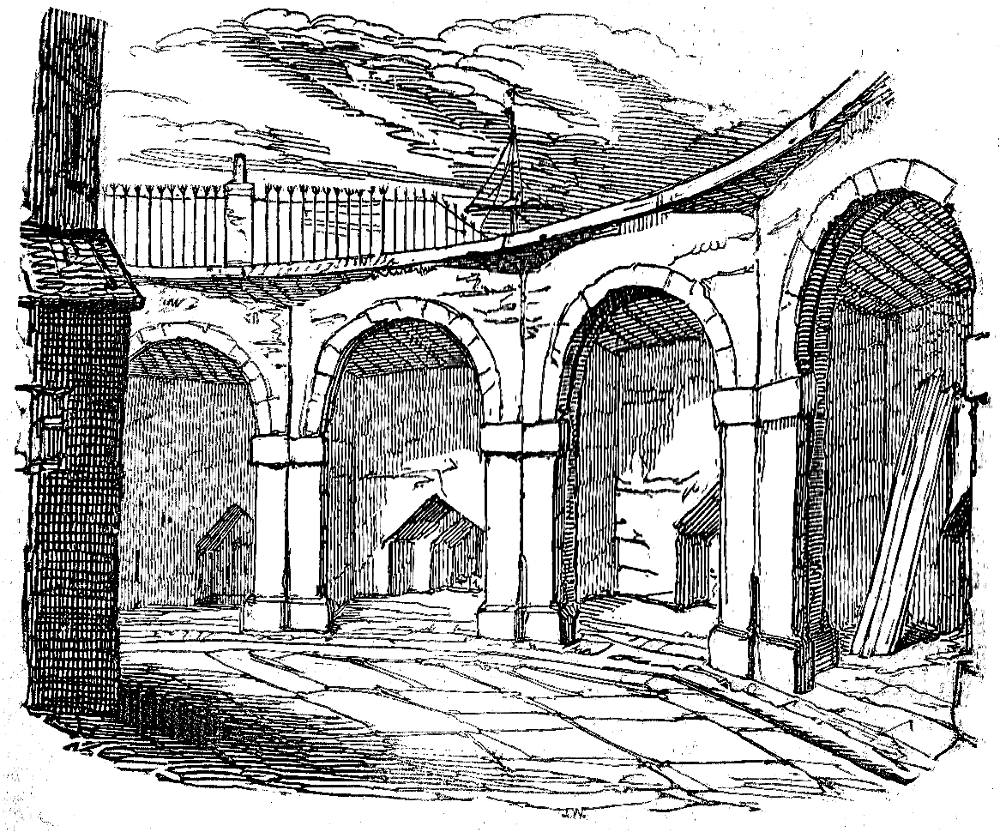

The Menagerie. — George Cruikshank. Eighth instalment, August 1840 number. Fifty-seventh illustration and thirty-third wood-engraving in William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. A Historical Romance. Illustration for Book the Second, Chapter XIX. 7.9 cm high x 9.6 wide, vignetted, p. 243: running head, "The Menagerie." [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Complemented

Mary had now removed her court to Whitehall. But she frequently visited the Tower, and appeared to prefer its gloomy chambers to the gorgeous halls in her other palaces. One night, an order was received by Hairun, the bearward, who had charge of the wild animals, that, on the following day, the Queen would visit the menagerie. Preparations were accordingly made for her reception; and the animals were deprived of their supper, that they might exhibit an unusual degree of ferocity. But though Hairun starved the wild beasts, he did not act in like manner towards himself. On the contrary, he deemed it a fitting occasion to feast his friends, and accordingly invited Magog, his dame, the two other giants, Xit, Ribald, and the pantler and his spouse, to take their evening meal with him. The invitation was gladly accepted; and about the hour of a modern dinner, the guests repaired to the bearward's lodgings, which were situated in the basement chamber of the Lions' Tower. Of this structure, nothing but an arched embrasure, once overlooking the lesser moat, and another subterranean room, likewise boasting four deep arched recesses, but constantly flooded with water, now remain. A modern dwelling-house, tenanted by the former keeper of the menagerie in the fortress, occupies the site of the ancient fabric. [Chapter XIX. — How Queen Mary visited the Lions' Tower; How Magog gave his Dame a Lesson; And How Xit conquered a Monkey, and was bested by a Bear," p. 540]

In this way, the meal was concluded, and it was followed by a plentiful supply of ale, hydromel, bragget, and wine. Nor did Peter Trusbut forget to slip the stone bottle of distilled water into Magog's hand, recommending him on no account to let Xit taste it — a suggestion scrupulously observed by the giant. His guests having passed a merry hour over their cups, Hairun proposed to conduct them over the menagerie, that they might see what condition the animals were in.

The proposal was eagerly accepted, and providing torches, the bearward led them into a small court, communicating by a low arched door with the menagerie. It was then as now, (for the modern erection, which is still standing though wholly unused, followed the arrangement of the ancient structure, and indeed retains some of the old stone arches), a wide semicircular fabric, in which were contrived, at distances of a few feet apart, a number of arched cages, divided into two or more compartments, and secured by strong iron bars.

A high embattled wall of the same form as the inner structure faced on the west a small moat, now filled up, which flowed round these outworks from the base of the Middle Tower to a fortification, now also removed, called, from its situation, the Lions' Gate, where it joined the larger moat.

Opposite the dens stood a wide semicircular gallery, defended by a low stone parapet, and approached by a flight of steps from the back. It was appropriated exclusively to the royal use.

The idea of maintaining a menagerie within the Tower, as an appendage to their state, was, in all probability derived by our monarchs, as has been previously intimated, from the circumstance of the Emperor Frederick having presented Henry the Third with three leopards, in allusion to his coat of arms, which animals were afterwards carefully kept within the fortress. Two orders from this sovereign to the sheriffs of London, in reference to a white bear, which formed part of his live stock, are preserved; the first, dated 1253, directing that fourpence a day (a considerable sum for the period) be allowed for its sustenance; and tho second, issued in the following year, commanding "that for the keeper of our white bear, lately sent us from Norway, and which is in our Tower of London, ye cause to be had one muzzle and one iron chain, to hold that bear without the water; and one long and strong cord to hold the same bear when fishing in the river of Thames." Other mandates relating to an elephant appear in the same reign, in one of which it is directed — "that ye cause without delay to be built at our Tower of London one house of forty feet long, and twenty feet deep, for our elephant; providing that it be so made and so strong, that when need be, it may be fit and necessary for other uses. And the cost shall be computed at the Exchequer." A fourth order appoints that the animal and his keeper shall be found with such necessaries "as they shall reasonably require." The royal menagerie was greatly increased by Edward the Third, who added to it, amongst other animals, a lion and lioness, a leopard, and two wild cats; and in the reign of Henry the Sixth the following provisions was made for the keeper: — "We of our special grace have granted to our beloved servant, Robert Mansfield, esquire, marshall of our hall, the office of keeper of the lions, with a certain place which hath been appointed anciently within our said Tower for them; to have and to occupy the same, by himself or by his sufficient deputy, for the term of his life, with the wages of sixpence per day for himself, and with the wages of sixpence per day for the maintenance of every lion or leopard now being in his custody, or that shall be in his custody hereafter." From this it will appear that no slight importance was attached to the office, which was continued until recent times, when the removal of the menagerie rendered it wholly unnecessary.

Dazzled by the lights, and infuriated with hunger, the savage denizens of the cages set up a most terrific roaring as the party entered the flagged space in front of them. Hairun, who was armed with a stout staff, laid about him in right earnest, and soon produced comparative tranquillity. Still, the din was almost deafening. The animals were numerous, and fine specimens of their kind. There were lions in all postures, — couchant, dormant, passant, and guardant; tigers, leopards, hyaenas, jackals, lynxes, and bears. Among the latter, an old brown bear, presented to Henry the Eighth by the Emperor Maximilian, and known by the name of the imperial donor, particularly attracted their attention, from its curious tricks. At last, after much solicitation from Dames Placida and Potentia, the bearward opened the door of the cage, and old Max issued forth. [Chapter XIX. — How Queen Mary visited the Lions' Tower; How Magog gave his Dame a Lesson; And How Xit conquered a Monkey, and was bested by a Bear," p. 242-44]

Commentary

The Lions' Tower, site of the royal menagerie, once occupied the westernmost location on Tower Wharf. For six hundred years the court could visit such outlandish creatures as lions, tigers, monkeys and elephants, zebras, alligators, bears, and kangaroos. Founded by King John in the early 1200s, the Royal Menagerie became home to more than sixty animal species, most of whom were exotic imports rather than indigenous to the British Isles. Courts all over Europe exchanged such exotic beasts as regal gifts, curiosities only the upper aristocracy could observe. During the reign of Henry III, for example, the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II, presented the English King with three leopards, about 1235. Historical records indicate that Edward I ordered the construction of the semi-circular bastion or barbican in 1277; this area was later named the Lion Tower, to the immediate west of the Middle Tower. Records from 1335 indicate the purchase of a lock and key for the lions and leopards, also suggesting they were located near the western entrance of the Tower. By the 1500s that area was called the Menagerie. By the 18th century, the menagerie was open to the public; admission cost three half-pence or the supply of a cat or dog to be fed to the lions. By the end of the eighteenth century, that admission price had increased to nine pence.

By the time that Cruikshank and Ainsworth were undertaking monthly perambulations of the Tower of London, the old bastion formerly housing the Royal Menagerie was devoid of life, as the present illustration showing empty enclosures indicates. Twelve years later, during the general renovation of the Tower of London, after the death of King George IV, the government decided to sweep away the unused menagerie cages and had the remaining animals relocated to the Regent's Park Zoo in North London. Perhaps Ainsworth's story of the dwarf Xit's encounter with a chestnut-stealing ape and the bear, Max, has its origin in contemporary accounts of a lion biting a soldier and a monkey biting a sailor, Ensign Seymour. A particularly famous inhabitant of the zoo was Old Martin, a grizzly bear which the Hudson's Bay Company presented to George III in 1811. The old barbican that housed the menagerie, however, remained until 1852 (much as Cruikshank had depicted it in 1840) because Copps, the last keeper, had been granted the use of the Lion Tower for life.

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. 11 September 2017.

Department of Environment, Great Britain. The Tower of London. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967, rpt. 1971.

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Pitkin Pictorials. Prisoners in the Tower. Caterham & Crawley: Garrod and Lofthouse International, 1972.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 19 October 2017