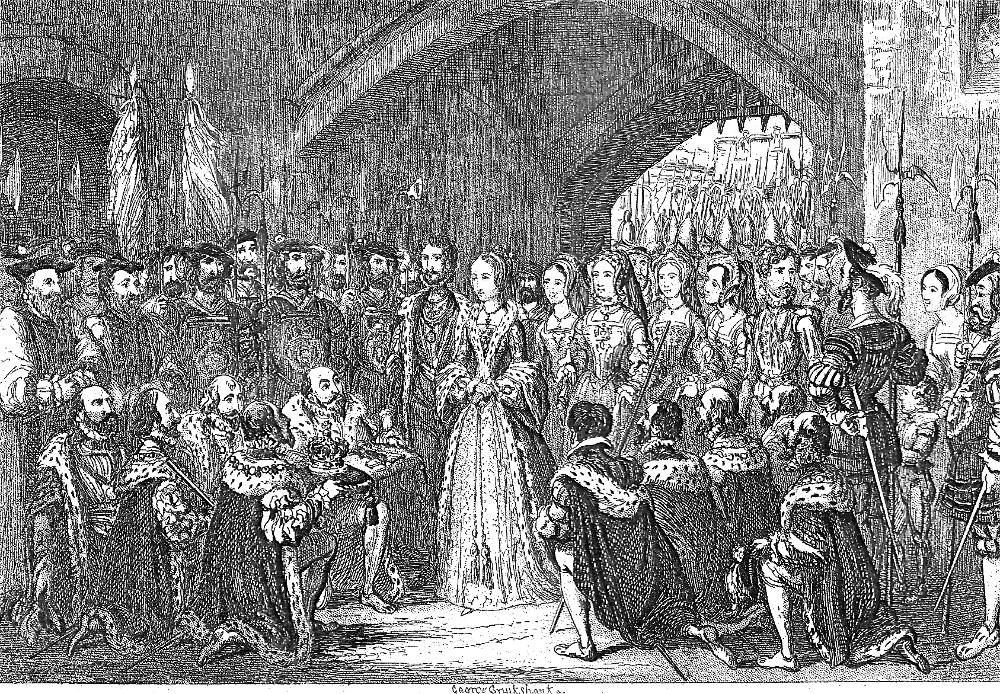

Queen Jane's Entrance to The Tower. — George Cruikshank. January 1840. Sixth illustration in William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. 9.7 cm high by 14.5 cm wide, framed, facing page 16. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

Proceeding along the platform by the side of a low wall which guarded the southern moat, Jane passed under a narrow archway formed by a small embattled tower connected with an external range of walls facing Petty Wales. She next traversed part of the space between what was then called the Bulwark Gate and the Lion’s Gate, and which was filled with armed men, and passing through the postern, crossed a narrow stone bridge. This brought her to a strong portal, flanked with bastions and defended by a double portcullis, at that time designated the Middle Tower. Here Lord Clinton, Constable of the Tower, with the lieutenant, the gentleman porter, and a company of warders, advanced to meet her. By them she was conducted with much ceremony over another stone bridge, with a drawbridge in the centre, crossing the larger moat, to a second strong barbican, similarly defended and in all other respects resembling the first, denominated the Gate Tower. As she approached this portal, she beheld through its gothic arch a large assemblage, consisting of all the principal persons who had assisted at the previous ceremonial, drawn up to receive her. As soon as she emerged from the gateway with her retinue, the members of the council bent the knee before her. The Duke of Northumberland offered her the keys of the Tower, while the Marquess of Winchester, lord treasurer, tendered her the crown.

At this proud moment, all Jane's fears were forgotten, and she felt herself in reality a queen. At this moment, also, her enemies, Simon Renard and De Noailles, resolved upon her destruction. At this moment, Cuthbert Cholmondeley, who was placed a little to the left of the queen, discovered amid the by-standers behind one of the warders a face so exquisitely beautiful, and a pair of eyes of such witchery, that his heart was instantly captivated; and at this moment, also, another pair of very jealous-looking eyes, peering out of a window in the tower adjoining the gateway, detected what was passing between the youthful couple below, and inflamed their owner with a fierce and burning desire of revenge. [Book One, Chapter I. — "Of the Manner in which Queen Jane Entered The Tower of London," p. 17]

Commentary

It has been, for years, the cherished wish of the writer of the following pages, to make the Tower of London — the proudest monument of antiquity, considered with reference to its historical associations, which this country or any other possesses, — the groundwork of a Romance; and it was no slight satisfaction to him, that circumstances, at length, enabled him to carry into effect his favourite project, in conjunction with the inimitable Artist, whose designs accompany the work.

Desirous of exhibiting the Tower in its triple light of a palace, a prison, and a fortress, the Author has shaped his story with reference to that end; and he has also endeavoured to contrive such a series of incidents as should naturally introduce every relic of the old pile, — its towers, chapels, halls, chambers, gateways, arches, and drawbridges — so that no part of it should remain un-illustrated. — William Harrison Ainsworth, "Preface," pp. iii-iv.

In this particular engraving, Cruikshank's forty architectural studies in the book's wood-engravings combine with his dramatic realisations in steel-engravings of key scenes in the action of the novel, producing a binary effect, of seeing the Tower and its precincts as they were in 1840, and of seeing those same environs as the theatrical setting of grand events that played out on the national stage in 1553. Ainsworth was indeed fortunate to have the opportunity to collaborate on this mixed-media project with that "inimitable Artist" George Cruikshank, established in the minds of the reading public as the illustrator of both The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress and Sketches by Boz Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People, and therefore as something of a visual authority on London. As a present-day writer has remarked of the forty-eight-year-old graphic designer's contribution to the project,

George Cruikshank has given concrete life to the Tower's past, creating figures that convincingly take command of the stage offered by its charged spaces and, like the acting of Henry Irving, appear as if momentarily illuminated by flashes of lightning. Cruikshank’s pictures stand alone, like glimpses of a strange dream, drawing the viewer into a compelling emotional universe with its own logic, peopled with its own inhabitants and where it is too readily apparent what is going on. [Gentle Author, "The Bloody Romance of the Tower," 2010]

Such is very much the case with Cruikshank's depiction of Jane's initial, triumphal entrance to the Tower of London and Ainsworth's romance. The crowded scene of Queen Jane and her procession of courtiers and guards might be any Renaissance group study of a female monarch and her attendants (Queen Elizabeth I or Queen Mary Tudor, perhaps). However, Cruikshank here emphasizes the presence of so many armed men to imply the constant threat under which she lives once she accepts the crown. The accompanying passage at the close of the first chapter reveals what the illustrator does not — Lady Jane Grey's tears as she apprehends her vulnerability as the Duke of Northumberland's puppet-queen (and, she realizes too late, a mere place-holder until he can seize the reins of power for himself). Her all-too-normal reaction to such stress indicates her sensitivity, renders her more worthy of the reader's sympathy, and brings a somewhat shadowy historical figure to life. Although Cruikshank may make her too wasp-waisted, his intention seems to have been to foil the high drama of 1553 with the tranquil scenes that the Tower presented himself and Harrison Ainsworth in their monthly research walks about the place in 1840.

Cruikshank describes neither the recent storm nor the discharge of ordnance from the riverside batteries that has announced her arrival. Although five Dukes in ermine-lined cloaks flank her slender figure on either side, the lines of halberdiers to one side and behind her through the open portal and raised portcullis reveal that, in modern parlance, security is tight. Although Cruikshank has positioned Jane's ambitious husband, Lord Guildford Dudley, to her right (stage left), "his esquire, the young and blooming Cuthbert Cholmondeley," Ainsworth's romantic hero, is absent from the frame since no such youth in white satin is evident. The balding nobleman nearest Jane to the left must be the power-broker, Northumberland, for he is presenting her with the keys to the Tower on a velvet cushion; beside him, the Marquess of Winchester holds the crown. Her arch enemy, the demonic Spanish ambassador, Simon Renard (right), fingers the hilt of his sword. The nobleman turned to Renard is De Noailles, another sworn enemy of the young Queen. Thus, although Ainsworth makes Cholmondeley his focus, Cruikshank focusses upon the slender-waisted Lady Jane Grey and her adversaries. However, if the viewer studies the composition carefully, he or she will discover a malevolent visage from by a turret window, exactly as in the text.

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. 11 September 2017.

The Gentle Author. "The Bloody Romance of the Tower." Spitalfields Life. 17 May 2011.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 29 September 2017