The Burning of Edward Underhill on the Tower Green. — George Cruikshank. Eighth instalment, August 1840 number. Sixtieth illustration and twenty-sixth steel-engraving in William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. A Historical Romance. Illustration for Book the Second, Chapter XX. 10 cm high x 14.1 wide, framed, facing p. 256: running head, "The Stake." The scene affords Cruikshank an unusual opportunity in his program to indulge his taste for the bizarre and the horrific as the Protestant fanatic and would-be assassin of Mary Tudor meets a gruesome death at the stake, a tour-de-force of state-sponsored sadism with which Cruikshank ends the eighth monthly instalment. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

A deep and awful silence now prevailed throughout the concourse. Not a breath was drawn, and every eye was bent upon the victim. He was seized and stripped by Mauger and Wolfytt, the latter of whom dragged him to the stake, which the poor zealot reverently kissed as he reached it, placed the iron girdle round his waist, and riveted it to the post. In this position, Underhill cried with a loud voice, "God preserve Queen Jane! and speedily restore her to the throne, that she may deliver this unhappy realm from the popish idolaters who would utterly subvert it."

Several voices cried "Amen!" and Wolfytt, who was nailing the girdle at the time, commanded him to keep silence, and enforced the order by striking him a severe blow on the temples with the hammer.

"You might have spared me that, friend," observed Underhill, meekly. And he then added, in a lower tone, "Have mercy upon me, O Lord, for I am weak! O Lord heal me, for all my bones are vexed!"

While the fagots were heaped around him by Mauger and Nightgall, he continued to pray fervently; and when all was made ready, he cried, "Dear Father, I beseech thee to give once more to this realm the blessing of thy word, with godly peace. Purge and purify me by this fire in Christ’s death and passion through thy spirit, that I may be an acceptable burnt-offering in thy sight. Farewell, dear friends. Pray for me, and pray with me."

As he spoke, Nightgall seized a torch and applied it to the fagots. His example was imitated by Mauger and Wolfytt, and the pile was speedily kindled. The dry wood crackled, and the smoke rose in thick volumes. the flames then burst forth, and burning fast and fiercely, cast a lurid light upon the countenances of the spectators, upon the windows of Saint Peter's chapel, and upon the grey walls of the White Tower. As yet, the fire had not reached the victim; the wind blowing strongly from the west, carried it aside. But in a few seconds it gained sufficient ascendancy, and his sufferings commenced. For a short space, he endured them without a groan. But as the flames mounted, notwithstanding all his efforts, the sharpness of the torment overcame him. Placing his hands behind his neck, he made desperate attempts to draw himself further up the stake, out of the reach of the devouring element. But the iron girdle effectually restrained him. He then lost all command of himself; and his eyes starting from their sockets—his convulsed features — his erected hair, and writhing frame — proclaimed the extremity of his agony. He sought relief by adding to his own torture. Crossing his hands upon his breast, and grasping either shoulder, he plunged his nails deeply into the flesh. It was a horrible sight, and a shuddering groan burst from the assemblage. Fresh fagots were added by Nightgall and his companions, who moved around the pyre like fiends engaged in some impious rite. The flames again arose brightly and fiercely. By this time, the lower limbs were entirely consumed; and throwing back his head, and uttering a loud and lamentable yell which was heard all over the fortress, the wretched victim gave up the ghost. A deep and mournful silence succeeded this fearful cry. It found an heco in every breast. [Chapter XX. —"How Edward Underhill was Burnt on Tower Green," pp. 255-256]

Commentary

Cruikshank's illustration of Underhill's being executed not as an assassin but as a religious radical is a metonymy for the persecution of Protestants under the reign of Queen Mary I, and a grisly piece of realism in a "romance." W. H. Chesson in his small book on Cruikshank as a book illustrator singles out this illustration for special mention as stirring visceral feelings of revulsion and horror:

In Underhill, the Hot Gospeller, burning at the stake, his finger nails riveted to his bare shoulders while he bawls his last agony, Cruikshank shows the longevity of the Marian crime — the crime of creating fears and loathings, for here we have absolutely a reflective shudder, a naked confidence from an abominable place which we thought was cleansed by merciful years. No other figure in the gallery of Cruikshank's "Tower" is so vital as this dying man, but he drew a handsome Wyat, an executioner as repulsive as a ghoul, and groups — for instance Elizabeth and her escort on the steps of Traitor's Gate — which a stage manager of melodrama might to imitate. [Chesson, pp. 82-85]

The place at which the "Gospeller" Edward Underhill meets his death was the site of a number of other executions, to which a plaque now bears testimony. In addition to the two wives of Henry VIII to whom Ainsworth alludes, executed on 19 May 1836 and 13 February 1542, at a scaffold on that spot the following members of the nobility met their deaths: William, Lord Hastings (June 1483); Margaret, Countess of Salisbury (27 May 1541); Jane, Viscountess Rochford (13 February 1842); Lady Jane Grey (12 February 1554); and Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex (15 February 1601). However, all of these members of the nobility fell under the blade of the headsman's axe, except for Anne Boleyn, whose head was severed by a French executioner's sword. Such an execution as Underhill's would hardly have been conducted within the precincts of the Tower of London. Moreover, as a traitor or one guilty of sedition (for he had made an attempt on the Queen's life), he would probably have been hanged, drawn, and quartered. No heretic was ever burned at the stake on Tower Green, although Mary certainly ordered the execution of a number of leading Protestants. Ainsworth connects the immolation of the fictional Underhill with such historical figures as Ripley by stipulating that he "was condemned for his religious opinions only" (254) as Mary had pardoned him as an assassin.

In this vivid illustration of Marian excesses, Cruikshank contrasts the "moody silence" of the spectators with the vigorous actions of the executioners: Nightgall to the left, Mauger to the right, and Wolfytt left of centre. The sooty black of the smoke above the roaring flames echoes the black garments of the Catholic prelates in the left-hand corner, while the flames of the growing conflagration illuminate the Chapel in the background and the faces of the impassive onlookers. Thus, Ainsworth synthesizes the historical fact of the Marian immolations with his fictional characters. Significantly, in the previous chapter Mary, visiting the Menagerie, is shocked to learn from Bedingfeld that the council has ordered Underhill's public execution since she had expressly pardoned him (if he agrees to a public recantation of his Protestant faith). Mary elects the time and place: "To-morrow at midnight, on the Tower-green" (247). Through this brief dialogue Ainsworth exonerates Mary of complete responsibility for the horrific execution, although with a sigh she acquiesces in the judgment of her council and signs the death-warrant, and Underhill adamantly refuses the opportunity that Mary has given him to save himself.

Other Scenes at St. Peter's Chapel on the Green

Above: Cruikshank's simple redering of the backdrop for the grisly execution of Edward Underhill, South view of St. Peter's Chapel on the Green. (wood-engraving, August 1840) [Click on image to enlarge it.]

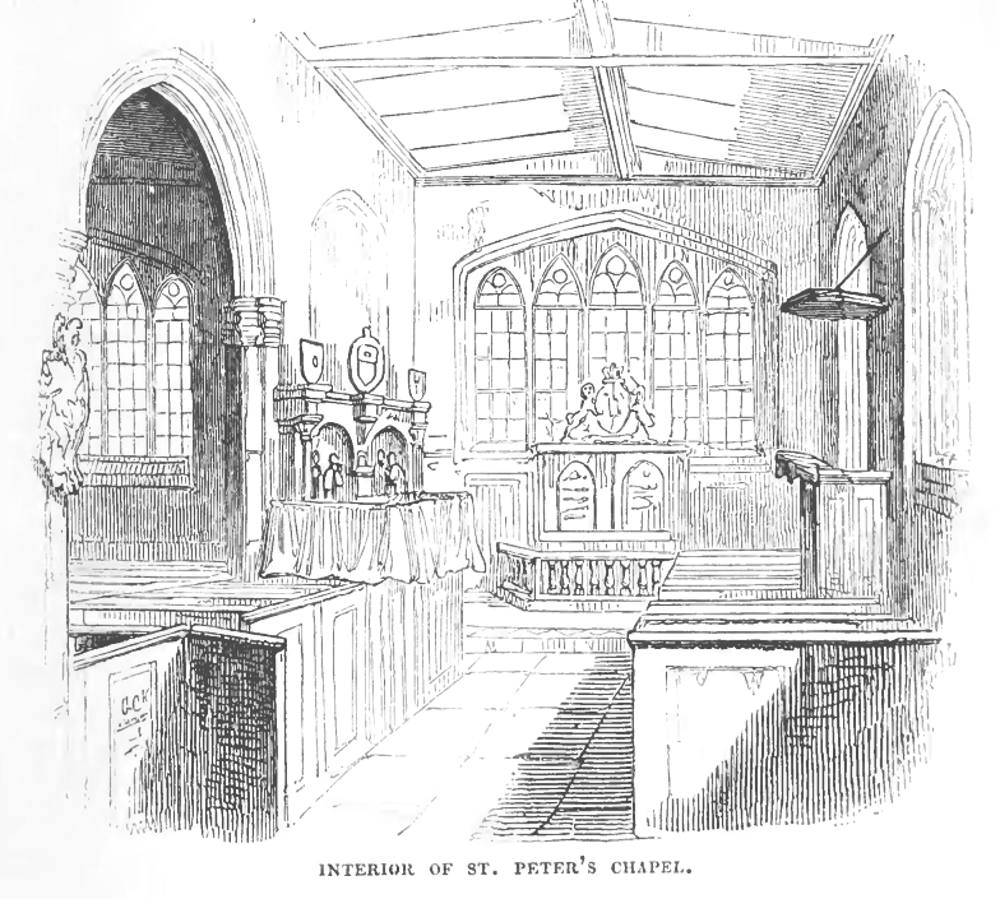

Above: Cruikshank's earlier wood-engraving of the quiet interior of the Chapel as it appeared in 1840, Interior of St. Peter's Chapel. (February 1840) [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. 11 September 2017.

Department of Environment, Great Britain. The Tower of London. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967, rpt. 1971.

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Pitkin Pictorials. Prisoners in the Tower. Caterham & Crawley: Garrod and Lofthouse International, 1972.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 25 October 2017