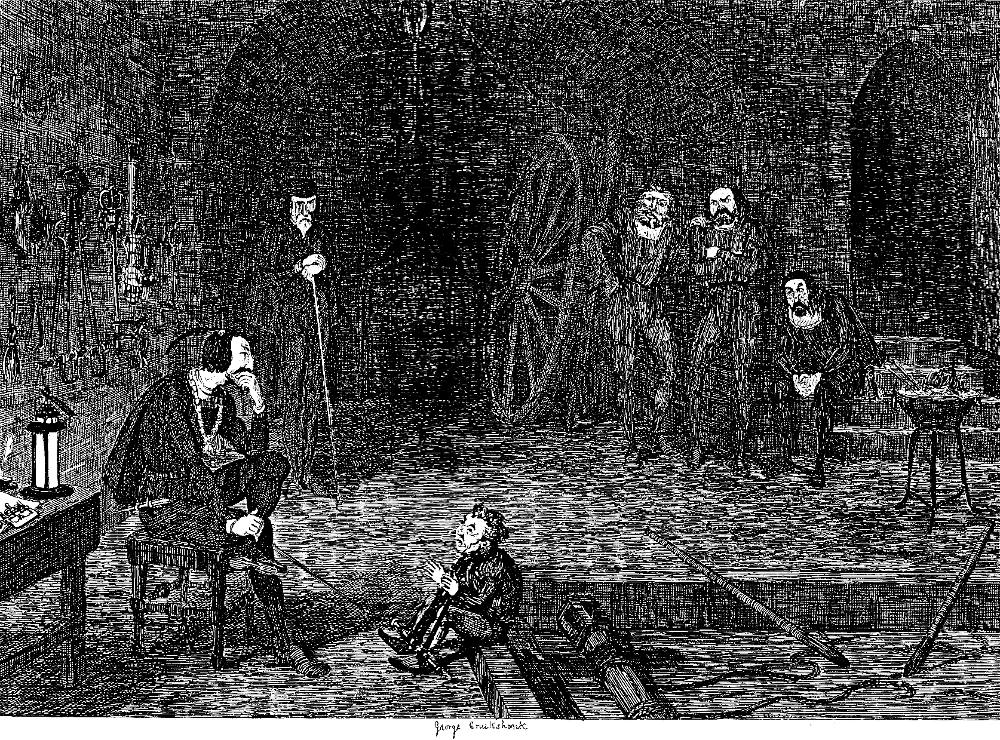

Xit wedded to the "Scavenger's Daughter. — George Cruikshank. Ninth instalment, September 1840 number. Sixty-fourth illustration and and twenty-eighth steel-engraving in William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. A Historical Romance. Illustration for Book the Second, Chapter XXIII. 10 cm high x 14.2 wide, framed, facing p. 279: running head, "The Scavenger's Daughter." The dark plate does not suggest the extent of Xit's sudden depression as he realizes that his having assisted Courtenay in his recent escape is now resulting in Nightgall's torturing him in order to extract information about those responsible. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

"Bring forward the prisoner," cried Renard, with a stern voice, but without turning his head.

Upon this, Nightgall seized Xit by the hand, and dragged him towards the table. A quarter of an hour elapsed, during which Renard continued writing as if no one were present; and Xit, who at first was half dead with fright, began to recover his spirits.

"Your excellency sent for me." he ventured, at length.

"Ha!" ejaculated Renard, pausing and looking at him, "I had forgotten thee."

“A proof that my case is not very dangerous," thought Xit. "I must let this proud Spaniard see I am not so unimportant as he seems to imagine. Your excellency I presume, desires to interrogate me on some point,” he continued aloud. "I pray you proceed without further delay."

"Is it your excellency's pleasure that we place him on the rack?" interposed Nightgall.

"Or shall we begin with the thumb-screws," observed Mauger, pointing to a pair upon the table; "I dare say they will extort all he knows. It would be a pity to stretch him out."

"I would not be an inch taller for the world," rejoined Xit, raising himself on his tiptoes.

"I have a suit of irons that will exactly fit him," observed Wolfytt, going to the wall, and taking down an engine that looked like an exaggerated pair of sugar-tongs. "These were made as a model, and have never been used before, except on a monkey belonging to Hairun the bearward. We will wed you to the 'Scavenger's Daughter,' my little man."

Xit knew too well the meaning of the term to take any part in the merriment that followed this sally.

"The embraces of the spouse you offer me are generally fatal," he observed. "I would rather decline the union, if his excellency will permit me."

"What is your pleasure?" asked Nightgall, appealing to Renard.

"Place him in the irons," returned the latter. "If these fail, we can have recourse to sharper means."

Xit would have flung himself at the ambassador's feet, to ask for mercy, but he was prevented by Wolfytt, who slipping a gag into his mouth, carried him into the dark recess, and, by the help of Mauger, forced him into the engine. Diminished to half his size, and bent into the form of a hoop, the dwarf was then set on the ground, and the gag taken out of his mouth.

"How do you like your bride?" demanded Wolfytt, with a brutal laugh.

"So little," answered Xit, "that I care not how soon I am divorced from her. After all," he added, "uncomfortable as I am, I would not change places with Magog."

This remark was received with half-suppressed laughter by the group around him, and Wolfytt was so softened that he whispered in his ear, that if he was obliged to put him on the rack, he would use him as tenderly as he could. "Let me advise you as a friend," added the tormentor, "to conceal nothing."

"Rely upon it," replied Xit, in the same tone. "I'll tell all I know — and more."

"That's the safest plan," rejoined Wolfytt, drily.

By this time, Renard having finished his despatch, and delivered it to Nightgall, he ordered Xit to be brought before him. Lifting him by the nape of his neck, as he would have carried a lap-dog, Wolfytt placed him on the edge of the rack, opposite the ambassador's seat. He then walked back to Mauger, who was leaning against the wall near the door, and laid his hand on his shoulder, while Nightgall seated himself on the steps. All three looked on with curiosity, anticipating much diversion. Sorrocold, who had never altered his posture, only testified his consciousness of what was going forward by raising his lacklustre eyes from the ground, and fixing them on the dwarf.

Wheeling round on the stool, and throwing one leg indolently over the other, Renard regarded the mannikin with apparent sternness, but secret entertainment. The expression of Xit's countenance, as he underwent this scrutiny, was so ludicrous, that it brought a smile to every face except that of the chirurgeon.

After gazing at the dwarf for a few minutes in silence, Renard thus commenced — "You conveyed messages to the Earl of Devonshire when he was confined in the Bell Tower?" [Chapter XXIII. — "HowXit was Imprisoned in the Constable Tower; and How he was wedded to the 'Scavenger's Daughter'," page 279]

Commentary

The surgeon is the only new character introduced in the interrogation scene. Simon Renard, the Spanish ambassador, having had Wolfytt install Xit in the compression machine devised by the Master of the Tower under Henry VIII, seems bemused. And well he might: Xit, desperate to buy time in order to effect an escape from the Constable Tower, tells his torturers Mauger, Nightgall, and Nightgall's assistant and the cunning Renard that the author of Courtney's escape from the Tower was Queen Mary herself, rather than Sir Thomas Wyat and the French ambassador, De Noailles. The figures in Cruikshank's illustration, set in the torture-chamber below the Constable Tower, correspond to those in the narrative: Renard, looking quizzically at Xit, is in the foreground; in the background, standing to the left, is the chirurgcon Sorrocold:

his attenuated limbs appearing yet more meagre from the tight-fitting black hose in which they were enveloped, The chirurgcon wore a short cloak of sad-coloured cloth, and a doublet of the same material. His head was covered by a flat black cap, and a pointed beard terminated his hatchet-shaped, cadaverous face. His hands rested on a long staff, and his dull heavy eyes were fixed upon the ground.

The bare-headed Mauger is the centre of the trio in the background to the right; the other two are Nightgall (seated) and Wolfytt. The dungeon itself is necessarily somewhat gloomy, but Cruikshank has provided every detail that Ainsworth has described:

On the side where Renard sat, the wall was decorated with thumb-screws, gauntlets, bracelets, collars, pincers, saws, chains and other nameless implements of torture. To the ceiling was affixed a stout pulley with a rope, terminated by an iron hook, and two leathern shoulder-straps. Opposite the door-way stood a brasier, filled with blazing coals, in which a huge pair of pincers were thrust; and beyond it was the wooden frame of the rack, already described, with its ropes and levers in readiness. Reared against the side of the deep dark recess, previously mentioned, was a ponderous wheel, as broad in the felly as that of a waggon, and twice the circumference. This antiquated instrument of torture was placed there to strike terror into the breasts of those who beheld it—but it was rarely used. Next to it was a heavy bar of iron employed to break the limbs of the sufferers tied to its spokes. [Chapter XXIII. — "HowXit was Imprisoned in the Constable Tower; and How he was wedded to the 'Scavenger's Daughter'," page 278]

Through the judicious use of chiaroscuro Cruikshank throws the bodies of the supporting cast into the deep shadows of the dungeon while highlighting in particular the faces of Simon Renard and Xit in the foreground with the lantern, lower left. The picture admirably fills out the scene which Ainsworth narrates chiefly through dialogue.

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. 11 September 2017.

Department of Environment, Great Britain. The Tower of London. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967, rpt. 1971.

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Pitkin Pictorials. Prisoners in the Tower. Caterham & Crawley: Garrod and Lofthouse International, 1972.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 22 October 2017