Dante Rossetti revolutionized painting and poetry, and he had a parallel affect on the development of mid-Victorian illustration. He only contributed to four books, producing a mere twelve illustrations, but his art had far-reaching implications. Widely admired, his work is the subject of a variety of interpretations, and it is probably impossible to arrive at a consensus of opinion. My aim here is to characterize his approach to illustration by outlining some of the key themes.

Rossetti, illustration and the use of painterly imagery

In keeping with the style of the Sixties, Rossetti transferred the language of painting to the arena of graphic art. Working initially in the late fifties, when illustration was still dominated by the comic cartoons of untutored designers such George Cruikshank and Richard Doyle, he was one of the first of the new generation to insist that book-images should enshrine the fundamental seriousness and academic standards of painting. Rossetti's approach, like that of his contemporaries, was comprehensive. In place of caricature, he emphasises anatomical correctness and draughtsmanship; humour is replaced by intellectual critique, psychological drama, yearning and idealized beauty; contemporary life, by medieval fancy and sexuality. Never less than idiosyncratic, Rossetti's illustrations are a curious blend of painterly exactitude, unexpected distortions, strange ornaments and private iconography. Intimate, personal and characterized by an absolute sense of expressive purposefulness, they naturally extend the 'poetic' vision of his paintings.

Lizzie Siddal's face in Rossetti's illustrations — The Weeping Queens from the illustration of "The Palace of Art"in the Moxon Tennyson. [Click upon thumbnails for larger images.]

Indeed, Rossetti viewed illustration as a smaller version of his image-making on oil or paper. The imagery of his painting makes a seamless blend with his illustration, and there are many examples of a cross-over from one domain to the other. This process is exemplified by the switch between the figures of the grieving queens in his work for Tennyson's Poems (1857) and his intimate drawings of Elizabeth Siddal. In the illustrations for Tennyson generally, the female characters have Lizzie's face: the ideal of beauty in the painting becomes the icon in the graphic design. There are also marked similarities between the treatment of space in the illustrations and the spatial schemes of his paintings. His graphic designs display the angular treatment of space that features in his watercolours of the fifties. Pictures such as The Marriage of St George and Princess Sabra (1857, Tate Britain, London) are intricate, intimate domains, liminal voids of doors and recessions, and the same is true of the cramped schemes appearing in The Music Master (1855), Tennyson'sPoems (1857), and his two books for his sister, Goblin Market (1862) and The Prince's Progress (1866).

Left: Beata Beatrix. Right: St. Cecilia from the illustration of "The Palace of Art"in the Moxon Tennyson.

[Click upon thumbnails for larger images.]

In each case, the imagery of the paintings nourished the imagery of the illustrations. Conversely, book-art allowed Rossetti to experiment with new visual schemes and ideas, and some of his printed images anticipate later developments in his paintings. It is noticeable, for example, that the figure of St. Cecilia in 'The Palace of Art' (Tennyson, 1857) is a clear prefiguration of the central figure in his later oil, Beata Beatrix (1862-64, Tate Britain, London). In both of these we have the eroticised treatment of the woman, neck outstretched, in Rossetti's own term, 'rapt' between heaven and earth, the sexual and the spiritual. The illustration even includes an annunciatory dove, a figure that returns in Beata Beatrix, where it is turned into a crimson dove bearing a poppy flower.

This process of synergy and symbiosis is typical of an artist whose poetry further embodies his artistic vision. In a certain sense, painting, illustration and verse are parallel schemes, modes of signification which draw strength from each other and are used alternatively, as a method of exploring and expressing Rossetti's singular artistic vision.

Rossetti as a visual interpreter of literary texts

As noted above, Rossetti's approach to the illustration of text is a complicated issue, the subject of extensive discussion. Taken as a whole, however, his treatments can be characterized as a matter of imaginative interpretation, rather than straightforward illustration. Uninterested in slavishly reproducing an author's details, he approached his written source as a starting point, as raw material which he interpreted in whatever way he saw fit. As he remarks in a famous and much-quoted letter to William Allingham, the only good commission is one which allows the artist to 'allegorize (on his) own hook on the subject of the poem, without killing for (himself) and everyone a distinct idea of the poet's' (quoted in Reid, 31-32). The effect he seeks (and largely achieves) is one of imaginative enhancement, a grafting on of new layers and dimensions of meaning which extend the text's resonance, complicate its range of implications, and suggest ever-expanding ways of making sense of it.

That said, Rossetti's illustrative strategy is resistant to easy categorization. The immediate question is a simple one: if his images interpret their texts, how is this done? And what, in terms of manipulation, does the artist do to interrogate his source material? Exploration of these issues does not yield to general answers, but is best explained by considering three examples of Rossettian visualization: his single illustration to Allingham's The Music Master; his treatment of Tennyson's 'The Palace of Art'; and the pictorial frontispiece and title page for his sister's collection of poems, Goblin Market .

Rossetti and The Music Master

Rossetti's The Maids of Elfen Mere. [Click upon thumbnail for larger image.]

Rossetti's earliest work in the field of illustration was a single design for William Allingham's book of poems, The Music Master (1855). The volume contained one other Pre-Raphaelite illustration by Millais, and seven apprentice pieces by the novice Arthur Hughes. Rossetti's illustration, for 'The Maids of Elfen Mere' (facing 202), is a work of extraordinary distinction: intensely beautiful as a work of art in its own right, it persuaded Edward Burne-Jones to give up holy orders and become an artist.

The aesthetic quality of the design needs no justification, but more demanding is the nature of Rossetti's response to Allingham's melancholy verse. Presented with material which is not easy to visualize, his interpretation reflects a close reading of the text's ambience and emotion.

Rossetti recreates some of Allingham's details. He shows the three maids of Elfen Mere 'Singing Songs' (202) as they spin, and he includes the 'Pastor's Son' (203) who loves them. He positions them in the 'spinning room' (202) and he includes other small details such as the village clock (although this incorrectly shows 1:15) rather than the 11.00 stipulated in the poem).

These details create a linkage, an oscillation of text and design, but Rossetti's prime interest is the re-visualization of the text's melancholy tone. Allingham's poem is an elegy, a lament for lost love and innocence, and Rossetti visualizes this idea in the form of the maidens. These are the very embodiment of ethereal wistfulness: sharing the same face, they gaze yearningly into some distant space which is contained outside the room and eerily suggests the existence of a mystical time 'Years ago, and years ago' (202).

Rossetti also visualizes the Pastor's Son who listens to their singing, but his averted gaze suggests that the maidens are entirely imaginary, the product of his yearning for some distant time or ideal state. The expression on his face implies that he has already lost them at the very moment that they appear to be in the room: at once alive and (perhaps) already dead, Rossetti shows him as a figure wrapped (like so many of his characters) in a sort of unwholesome dream.

Seeming to exist in a specific time and outside time, Rossetti's illustration is a powerful interpretation of a poem in which causality and sequence appear to have been lost. Loss is the theme, and this pervades the moment he shows, positioning his characters, in counterpoint to Allingham's, between here and now, what is and what was. It is a curious, haunting design, and one which offers and abstract representation of an opaque and troubling poem. At once a piece of personal 'allegorizing', here, at least, Rossetti preserves both his own interpretation and a 'distinct idea of the poet's'.

Rossetti and the Moxon Tennyson

Published by Edmund Moxon in 1857, and generally known as the Moxon Tennyson, Tennyson's Poems was the first to showcase the talents of all three of the leading Pre-Raphaelites. These were printed alongside a series of designs by the established (but old-fashioned) talents of Creswick, Horsley and Clarkson Stanfield. Rossetti contributed just four out of the total of more than fifty.

The most complicated of his contributions is the first illustration to 'The Palace of Art' (113). This intricate image embodies his emphasis on personal interpretation, and of all Pre-Raphaelite designs it is undoubtedly the most controversial. Rossetti's treatment of Tennyson's allegory does not yield to a simple reading: in part an illustration of the spirit of the poem, it also reads as an insolent parody that ridicules its high-minded verse. The artist's critical stance is epitomized by his choice of scene.

Presented with a dense catalogue of images, he illustrates St. Cecilia and the angel, a moment which is not, on the face of it, a particularly relevant one. Tennyson lists this as one of several epiphanies which register events of insight or ecstatic reverie. His lines provide the barest of details:

In a clear-walled city on the sea,

Near gilded organ-pipes, her hair

Wound with white roses, slept St. Cecily;

An angel looked at her [118].

This is simply a 'mood of mind' (117) to be relished by the narrator as part of a collection of psychological conditions. However, in Rossetti's treatment much has been changed. Tennyson's Cecilia is asleep, Rossetti's is ecstatically playing the organ; the poet's saint is merely looked at by the angel, while Rossetti's swoons under a passionate kiss. He also makes changes by introducing several new and (apparently irrelevant) details, notably the tiny figures drawing water and docking a ship; the sundial; and the curious guard who introduces a touch of the comic grotesque as he vacantly bites on an apple.

None of this makes any immediate sense in relation to specific lines, but the image can be decoded as a reading of the poem as a whole. Positioned as a head-piece, Rossetti's St. Cecilia reads not as a literal showing of a character who incidentally features in the text, but, I suggest, as a symbol of the narrator, the isolated soul who builds a 'palace of art' in which to contemplate every worldly 'mood' and spiritual experience. In Tennyson's treatment this vicarious engagement with the world ultimately leads to a sense of spiritual emptiness and guilt; Rossetti's, on the other hand, it is purely a matter of physical sensation. Figuring the narrator as a young woman in a state of arousal, he visualizes his character as a person sated by desire. Her body is distorted into an exaggerated emblem of female sexuality, her arms are outstretched, her throat exposed, and her back provocatively arched. The poet finds psychological emptiness, yet Rossetti only finds glut, the weary physical condition brought on by sensory overload. Tennyson suggests that the narrator/poet who experiences the world from afar must always undergo a sort of spiritual collapse, but Rossetti's figure symbolizes the poet who is perpetually wearied. Tennyson's is a notion of the moral writer; Rossetti's, one might say, of the exhausted Decadent. Rossetti's reading is in this sense a calculated subversion of the author's ethical seriousness, reducing his grand contemplation of the nature of experience and the way it is felt to a matter of sensuous or even sexual exhaustion.

Viewed in these terms eroticism is used to critique Tennyson's text. Yet Rossetti's attitude to his material is also characterized by a sort of wry humour. Tennyson speaks grandly of the perils of experiencing real life from afar, as a sort of intellectual exercise, but in Rossetti's design the 'real world' is shown in terms which are just as unappealing as the world of vicarious contemplation. The Palace of Art is described in the poem as a place where the best of humanity converge, from Shakespeare and Dante to Arthur and the classical gods; in the illustration, by contrast, humanity is systematically reduced from the heroic to the insignificant.

Rossetti's use of the mock-heroic is humorously realized by juxtaposing apparently unrelated details. For example, the ecstatic experience of the angel and saint is brought into bizarre conjunction with a soldier eating an apple. These seem utterly at odds, but in one move Rossetti ridicules the seriousness of the central group by placing it next to another image of earthly appetite. The eating of the apple becomes in this sense an ironic commentary on the sensuality of the saint and her angelic lover. One is reduced to the level of the other, and all experience becomes a matter of sating the senses. The grand is shrunk to the status of the gross; the unique to the level of the commonplace. The contrast mocks the notion of elevated experience and Rossetti completes his mockery by comparing the timeless saint with the frantic movement of the tiny figures around her. She may be the occupant of the idealized Palace of Art, but Rossetti implies that 'real life' is a matter of prosaic activity. All experience is in any case bound by time, and the artist reminds us of the limitations of earthly experience by including one of his signature emblems, a sundial.

Rossetti's response to Tennyson's poem is thus a curious mixture of inventive visualization — which uses a passing scene to condense its theme into a single frame — and critical pastiche. Fusing both seriousness and humour into one design, he celebrates the intense other-worldliness of Tennyson's imagery while simultaneously making fun of it. Such ambiguity of typical of Rossetti's 'allegorizing' for himself:aiming to respect and parody his source material at one and the same time, he expands the text by offering a shifting perspective, a variety of ways in which it should, or could, or might be read.

Rossetti's Interpretations of His Sister's Work

Goblin Market (1862) was the first of two sets of illustrations that Rossetti did for his sister. The second, The Prince's Progress , was completed in 1866, and for both works Rossetti provided a pictorial frontispiece and title-page, as well as two striking designs for the bindings.

Christina seems to have appreciated her brother's help. Writing in a letter of of 4 April 1865, she thanks Dante for his application of 'brotherly hands' (Letters of Christina Rossetti , 1, 244), and there is no doubt that her sibling's involvement was of material assistance in getting her work published and in procuring a readership once it appeared. What is not recorded is Christina's opinion as to how he had interpreted her poems: on this score, she was diplomatically (or perhaps instrumentally) silent. Such unresponsiveness is surprising, given that both sets of illustrations are deeply personal in effect, closely reflecting the artist's idiosyncratic approach to his material.

The illustrations for Goblin Market are downright provocative. Figured as a diptych of frontispiece and title-page, they represent a calculated movement between a sort of multifarious or open-ended interpretation — in which the artist struggles to register the title poem's curious fusion of apparent opposites — while privileging what he sees as the most important ingredients. These elements overlap and intermingle, creating a dense visual text.

The illustrated title-page is an intricate fusion of the poem's movement between innocence and experience, childhood and the travails of adult temptation. The image of the two sisters sleeping is a representation of the lines,

Golden head by golden head

Like two pigeons in one nest

Folded in each other's wings. [10]

Title-page, Cristina Rossetti's Goblin Market. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

and we can see how Rossetti suggests the sense of enclosure by bringing them into an embrace which is literally crammed into a tiny field (and is further stressed by the enclosing lines of the borders and title). But the artist keenly points to the ambivalence of the scene. The illustration is apparently child-like in its naivete, presenting the sisters as innocents; yet it subtly suggests that their intimacy is charged with a more adult awareness. Their embrace is more like that of lovers than of sisters, and their voluptuous forms barely accord with the idea of the sexual neutrality of childhood. In fact Rossetti shows them as both innocent children and eroticised young women: a reading which closely accords with the poem's bizarre alternation between the imagery of virginity ('two blossoms on one stem', 10) and sexual awareness (symbolized by the phallic detail of the 'wands of ivory', 11). This fusion of opposites is vividly extended in the interaction between the roundel above their heads, and in the treatment of their figures. The tiny vignette shows the goblin men with 'moon and stars' (11). This is drawn with a gaucherie that suggests the imagery of the nursery and, in so doing, strongly recalls the sing-song nature of the verse, and points to its status as a sort of cautionary tale for the very young. Yet the positioning of the roundel also suggests that the supernatural figures have invaded their dreams: no longer quite so naïve, the girls' thoughts are occupied, even at the moment when they are apparently at their most innocent, with thoughts of (goblin) men.

The title-page acts, in other words, like a true frontispiece, a visual prefiguration of the oxymoron that unfolds in the following pages. The title 'Goblin Market' implies 'fairy tale' or 'nursery tale', but Rossetti points to its curious mediation of adult themes in the form of a story for children. By combining adult and child-like imagery in one frame, he alerts the reader as to what should be anticipated in his sister's text.

Somewhat paradoxically, he is much less even-handed in the 'real' frontispiece, which is first image the reader sees when s/he opens the book. This makes no attempt to present a balanced interpretation of the text; on the contrary, it reads (or 'allegorizes') the poem entirely in Dante's terms, on his 'own hook'. Rossetti's prime interest is in suppressing the poem's spiritual content — which is often read as a representation of Christian resistance to temptation — by focusing on its shocking treatment of sexuality. To that end he privileges some elements, exaggerates or distorts others, adds details of his own, and extends the poem's expressive range by drawing on a variety of allusions. He further deepens the poem's psychological associations, the underlying mental condition which drives what he sees as its emphasis on sexuality. In both cases he deploys a variety of emblematic details. Lorraine Kooistra has written at length about the connection between Rossetti's work for his sister and emblem books, and there can be no doubt that he draws on a range of sign-systems that were intelligible to the original viewer, but have to be reconstructed for the reader/viewer of today.

He stresses the poem's eroticism by showing Laura as a voluptuous young woman with a sensuous face and throat, fleshly lips and a figure literally bursting at the seams. This type of representation is very much a commonplace of the time, stressing the stereotypical connection, as outlined in physiognomical textbooks, between voluptuous bodies and sexuality (Walker, 252-53). It also epitomizes the Rossettian type of sexuality, of body rather than soul, Fanny Cornforth rather than Elizabeth Siddal. Drawing on an imagery that otherwise appears in paintings such as The Blue Bower (1865, Barber Institute, University of Birmingham, England), Rossetti presents another version of what J. B. Bullen has described as the 'fantasy world of unlimited sexuality' which is located in 'remote historical (or entirely imaginary) period' (89).

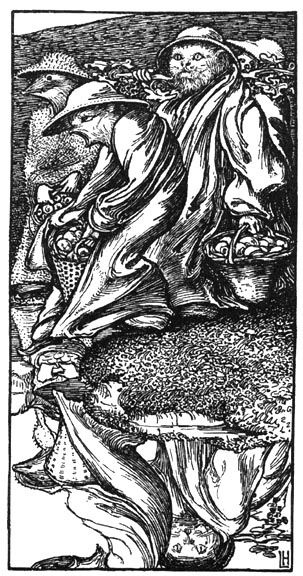

"Buy from Us with a Golden Curl", Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

Indeed, the illustration graphically illustrates a Laura whose 'last restraint has gone' (GM, 5). Described only as having a 'sweet tooth' (7), this version of the character is shown robustly leaning forward into the goblins' space, self-confidently paying for her experience by cutting her 'golden curl' (7). 'Buy from us with a golden curl' is the inscription Dante uses as the caption, and the significance of the act, of cutting the hair with a tiny scissors (an detail that does not appear in the poem) should not be misunderstood. In Christina's poem the clipping of the locks suggests a sort of magical giving, perhaps of the soul; but in Dante's illustration it acts as a symbol of the loss of virginity. 'Breaking' or 'cutting' the 'virgin knot' was a commonplace expression of mid-Victorian culture, and in showing Laura cutting her hair with a (phallic) pair of scissors — an image he also deploys in his watercolour, The Marriage of St. George and Princess Sabra (1857, Tate Britain, London) — Dante uses an expression which had contemporary currency. In Victorian literature and art the hair on a woman's head was frequently a metonym for pubic hair, and the illustration's emphasis on this act, rather than the eating of the fruit, figures it as a bold and explicit representation of what Rossetti saw as the poem's central event.

The sexual theme is supported by many of the other details. Dante re-presents some of the exotic fruits and flowers described in the poem, and these would have been read at the time of production, as critics such as S. P. Smith have argued, as emblematic signs. Particular emphasis is placed on the apples (1), the symbols of temptation, here situated centre left, and again on the pomegranate (2), an emblem of yielding to desire, of biting the forbidden fruit, which recurs in Rossetti's late painting, Proserpine (1877, Tate Britain, London). Other details are more suggestive: registered on a microscopic scale, they underscore the sexual theme with the mischievous humour which was typical of Rossetti's response to even the most sonorous material. Most amusing is the treatment of phallic symbolism. Included perhaps only for voyeurs, Rossetti places sprouting mushrooms under Laura's knees; a bulrush to the centre left; and — entrapped in the bulrush's weedy stem — a lily, the eternal emblem of virginity. Apparently insignificant, this tiny detail crystallizes Laura's predicament in an acute visual form. Described in the poem as a 'lily from the beck' (5), Laura is indeed the innocent flower, metaphorically caught up and strangled by a weedy clump of (masculine) stalks.

Two illustrators represent the male figures in "Goblin Market": A detail from Dante Gabriel Rossetii's title page and three illustrations by Laurence Housman. Left: Rossetti's "Buy from Us with a Golden Curl". Three right: Housman's version of the animalistic men. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

The erotic theme is further developed in the visual treatment of the goblins. Critics have generally read the bestiality of the intruders as the symbols of animal instincts, and the same is clearly true of the illustration; animals and sexuality are connected in the poem, and explicitly in the pictorial frontispiece. However, the illustrator's interpretation of this linkage is typically idiosyncratic, and diverges from his sister's text. Dante noticeably re-drafts the connection by changing the manner of the linkage. In the poem the men as 'like' (GM , 19) animals, while in the illustration they are animals: simile becomes metaphor, and the comparison is reversed so that animal-like men become animals who only loosely resemble men (notably in their wearing of jakcets and trousers). In other words, the illustration intensifies the idea of bestiality by making the men quite literally into creatures: the anthropomorphic replaces the zoomorphic, and the artist places the bestiality of his 'men' at the forefront of his interpretation. This strategy differs quite radically from other visualizations, notably Laurence Housman's (1893), where the goblins seem to wear animal masks. In Rossetti's treatment, there can be no doubt whatsoever that these goblins are beasts: their animal natures are written in their very bodies and their animal instincts have transformed their shapes, like those of Odysseus's men at the hand of Circe, into the personification of baseness.

What is interesting, however, is Dante's enrichment of this idea by focusing on beasts whose associations have a direct bearing on the poem's central interest in Laura's psychology. The animals listed in the text generally connote her sexual desire, but the artist selects only those which explicitly connote sexuality and carry other meanings as well. These emblematic messages can be reconstructed by linking them the pseudo-scientific books of the time, notably James Redfield's Comparative Physiognomy: Resemblances Between Men and Animals (1852), which Rossetti almost certainly read.

At the rear of the pack is the rat, a straightforward sign of Laura's eroticism. Described by Redfield as an icon of sensuality, it visualizes her 'cupidity and lust' (70). Her sexuality is similarly stressed by the fish, the emblem of 'rapacious' appetite (81). The text details her insatiable desire, 'She sucked and sucked and sucked the more' (GM , 8), and the illustration grotesquely embodies it in the form of a staring piscine. But other animals take the reading into the more complicated domains of Laura's character. At the front of the pack is a purring cat, a symbol of cunning and unpredictability (Redfield, 30-31) which comments on Laura's incapacity to conform to her sister's narrow ideals. Like the cat, Laura is in need of sensual affection, and will do anything — including disobeying Lizzie — to get what she wants. Her quixotic nature is similarly suggested by the parrot, a creature that 'aspires to originality in everything' and is full of 'one-sided, strange, outlandish notions, the result of an unwillingness to follow' (321-2). Both animals suggest her curiosity and her desire to please herself, and these traits are re-visualized in the form of the owl. Often taken as the emblem of wisdom, it functions here as a sign of Laura's independence and desire to take control. It also suggests her duplicity: according to Redfield the owl is adept at subterfuge (37) and so, we might say, is the independently-minded Laura. Animal-imagery is thus used to suggest the workings of Laura's character. The poem shows her to be self-willed and easily tempted, but the illustration adds more layers to her psychological portrait.

So we can see how the frontispiece greatly enhances and complicates the reading of the poem. It seems, at first glance, to emphasise the sexual interpretation, but adds further information in the form of a neo-medieval bestiary. The effect is one of density and implication. Dante may be uninterested in the spiritual aspects of his sister's poem, but he vigorously represents Laura's sexuality and its underlying motivations.

Speaking more generally, Rossetti's frontispiece and title-page provide a complicated visual mediation of the poem's themes, linking the child-like and the adult, the sensual and the fairy-tale. The title-page seems like a voyeuristic scene from a proscribed visual text — the sort Victorian gentlemen perused in male company - while the frontispiece, with its caricature-style animals and condensed space, strongly evokes children's illustration. Such curious shifts and contrasts run through the poem and in making what seems a very singular interpretation Dante Rossetti ultimately achieves his goal of 'allegorizing...without spoiling a distinct idea of his own and the poet's'.

Bibliography

Allingham, William. The Music Master. London: Routledge, 1855.

Bullen, J. B. The Pre-Raphaelite Body. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998.

Cooke, Simon. 'Brotherly Hands: Dante Rossetti's Artwork for his Sister Christina'. 'The Review of the Pre-Raphaelite Society 14:3 (Autumn 2006): 15-26

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. Christina Rossetti and Illustration: A Publishing History. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2002.

Letters of Christina Rossetti, The. 2 vols. Ed. Anthony H. Harrison. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1997.

Redfield, James. Comparative Physiognomy, or Resemblances Between Men and Animals. New York: Redfield (for the author), 1852.

Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Eighteen Sixties , 1928; reprint, New York: Dover, 1975.

Rossetti, Christina. Goblin Market. London: Macmillan, 1862.

Smith, S. P. 'Dante Rossetti's Lady Lilith and the Language of Flowers' Arts Magazine , 53 (1979): 142-45.

Tennyson, Alfred. Poems. London: Moxon, 1857.

Walker, Alexander. The New Lavater. London: Cornish, 1859.

Last modified 6 November 2009