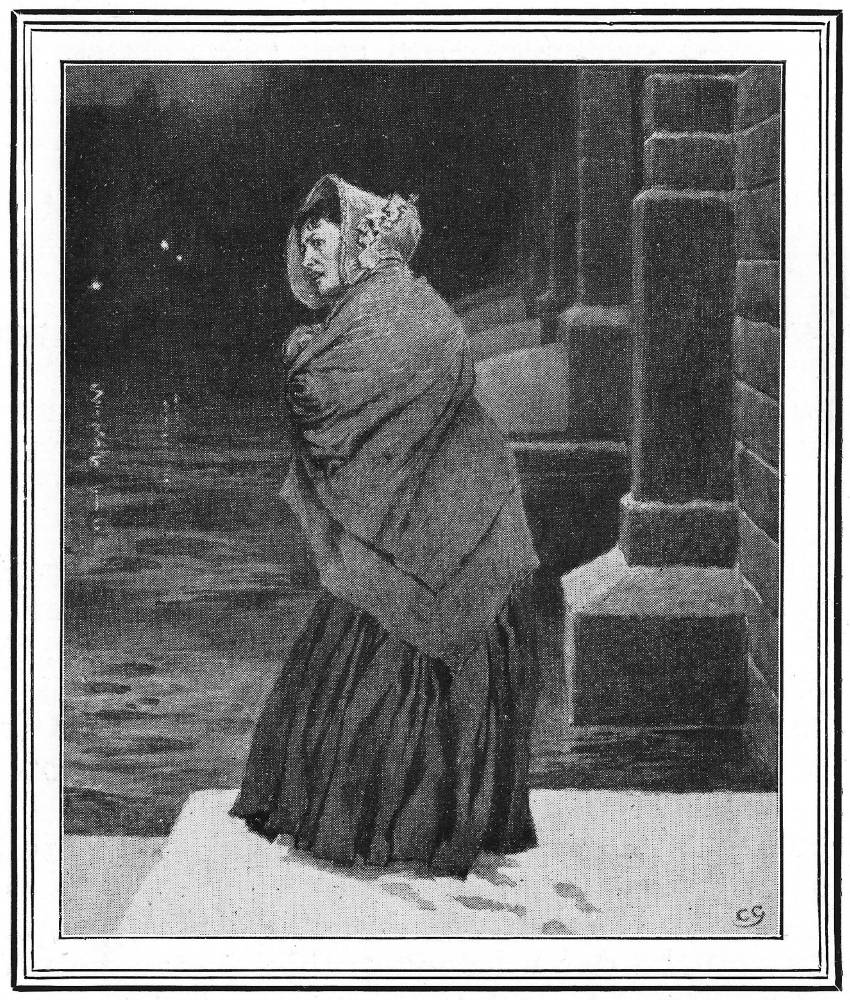

Meg at the River's brink

Charles Green

c. 1912

9.3 x 7.5 cm, exclusive of frame

Dickens's The Chimes, The Pears' Centenary Edition, II, 138.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Charles Green —> The Chimes —> Charles Dickens —> Next]

Meg at the River's brink

Charles Green

c. 1912

9.3 x 7.5 cm, exclusive of frame

Dickens's The Chimes, The Pears' Centenary Edition, II, 138.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

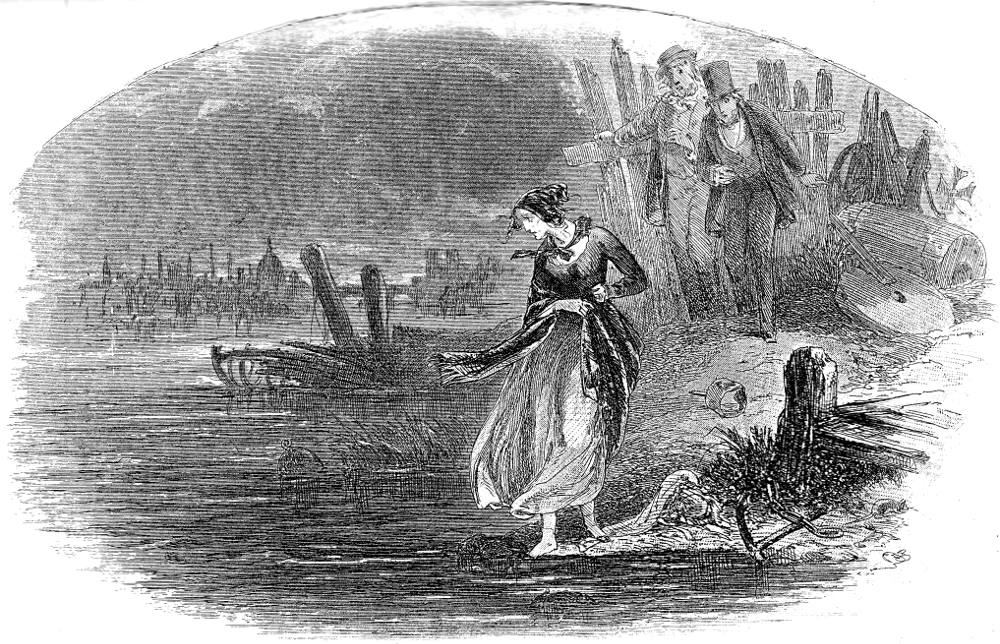

Putting its tiny hand up to her neck, and holding it there, within her dress, next to her distracted heart, she set its sleeping face against her: closely, steadily, against her: and sped onward to the River.

To the rolling River, swift and dim, where Winter Night sat brooding like the last dark thoughts of many who had sought a refuge there before her. Where scattered lights upon the banks gleamed sullen, red, and dull, as torches that were burning there, to show the way to Death. Where no abode of living people cast its shadow, on the deep, impenetrable, melancholy shade.

To the River! To that portal of Eternity, her desperate footsteps tended with the swiftness of its rapid waters running to the sea. He tried to touch her as she passed him, going down to its dark level: but, the wild distempered form, the fierce and terrible love, the desperation that had left all human check or hold behind, swept by him like the wind.

He followed her. She paused a moment on the brink, before the dreadful plunge. He fell down on his knees, and in a shriek addressed the figures in the Bells now hovering above them. ["Fourth Quarter," 137-38, 1912 edition]

Neither The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang An Old Year Out and a New Year In (1844) has a precise equivalent for this scene, when Meg, having been turned out of her lodgings for the landlord, Tugby, determines to throw herself and her child into the Thames, there being no future for either of them in a world dominated by the Cash Nexus. The 1844 illustration of Meg on the brink of the river is Richard Doyle's headpiece for "The Fourth Quarter," Margaret and her Child (see below), although realistic revision of 1912 lacks the metaphysical dimension of the ghostly Trotty and the goblins of the Chimes as impotent observers of the unfolding tragedy. Although Doyle shows Margaret on the bank of the Thames holding "her" child (not Lilian's, as Will Fern suggests), Green actually includes the pylons of New London Bridge (right), built in 1831; on the boat steps, lightly covered in snow, Meg in bonnet and shawl, looks upon agitated (though hardly "rolling") waters, desperation clearly written on her face. The caption for Meg at the River's brink is a lengthy quotation drawn from the previous page, so that the reading of the text and of the visual complement is integrated: "To the rolling River, swift and dim, where Winter Night sat brooding like the last dark thoughts of many who had sought a refuge there before her." The illustration, then, emphasizes Meg's enacting the role of many a desperate young woman before her, young woman homeless and friendless like the "fallen woman" Martha Endell in David Copperfield, which contains a similar scene for the novel's August 1850 instalment: The River (see below), by Dickens's usual illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne. Two years later, philanthropist Angela Burdett Coutts would approach the famous writer regarding her scheme for setting up a home for the rehabilitation of "fallen women" (prostitutes), Urania Cottage. However, Meg's situation is somewhat different from that of Martha Endell, for, although both are seamstresses who fall on hard times and contemplate suicide as the only escape, Meg has never stooped to prostitution, and is a widow with a young child, whereas Martha's fall has been occasioned not so much by dire economic circumstances, but by her own moral weakness. Nevertheless, in The Chimes Dickens does seem to be exploring in a preliminary fashion a highly wrought emotional state as well as a controversial issue into which he delves later in much greater depth — perhaps as a result of his experiences with the inmates of Urania Cottage.

Left: Doyle's scene of Meg's desperate final act, Margaret and Her Child. Right: Barnard's version of Martha's suicide averted, "Oh, the river!" she cried passionately. "Oh, the river!" (1872).

Above: Phiz's's August 1850 steel engraving of Martha's contemplating suicide by throwing herself into the Thames at Westminster, The River.

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes. Introduction by Clement Shorter. Illustrated by Charles Green. The Pears' Centenary Edition. London: A & F Pears, [?1912].

_____. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang An Old Year Out and a New Year In. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Daniel Maclise. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1844.

_____. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang An Old Year Out and a New Year In. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Daniel Maclise. (1844). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978. 137-252.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

Created 16 April 2015

Last modified 25 February 2020