Click on images to enlarge them and to obtain more information about them.

llen Wood’s Verner’s Pride was Keene’s final series for Once a Week. He provided seventeen illustrations for this sensational tale of inheritance and property, which also includes the stock-features of romance and the supernatural. Keene’s designs appeared from 28 June 1862 to 7 February 1863. Described by Reid as ‘splendid’ (p.123) and by Goldman as ‘masterly’ (p.233), these images are perhaps the most sophisticated and telling of his treatments, although they were never reprinted and have never previously been the subject of detailed analysis. As in the case of Evan Harrington so too with Verner’s Pride there was no contact between the artist and author – who seems to have taken no part whatever – and Keene was appointed, once again, on the basis of Lucas’s judgement.

The rationale for his commissioning of the artist may have been informed by a desire to mitigate what he would have seen as the exaggerated visual style of so many of the illustrations accompanying the Sensation novels appearing in periodicals such as M. E. Braddon’s Belgravia and George Smith’s Cornhill Magazine. Though he published Sensational novels in order to build an audience Lucas disliked Sensationalism and the formulaic responses of illustrators such as Louis Huart (in Belgravia), and his appointment of Keene is quite possibly informed by his desire to present images by an artist whom he knew would give a reading of integrity, based on what he found in the text rather than what he thought the illustrations should look like. Keene’s chameleon-like capacity to make his style fit the writing had already been demonstrated in his treatment of A Good Fight and Evan Harrington, and Lucas knew he could trust Keene to produce a response that would not fall into the conventionalities, so common among Sensational illustrations, of exaggerated, melodramatic gestures, modish modernity and fierce confrontations. Du Maurier provided exactly this sort of lurid excess in his engravings for Charles Adams’s thriller, The Notting Hill Mystery, and again in his designs for Reade’s Foul Play. Published in 1862 and 1868 in Once a Week, these series define the sort of visceral, overpowering experience that Keene denies in his work for Verner’s Pride.

Keene’s response to Wood’s novel is generally one in which he provides an alternative text, transforming the fiction from a straightforward thriller into a more reflective tale of change and sentiment. His approach can be conceptualized in terms of the ways in which he treats each of the key elements of the genre.

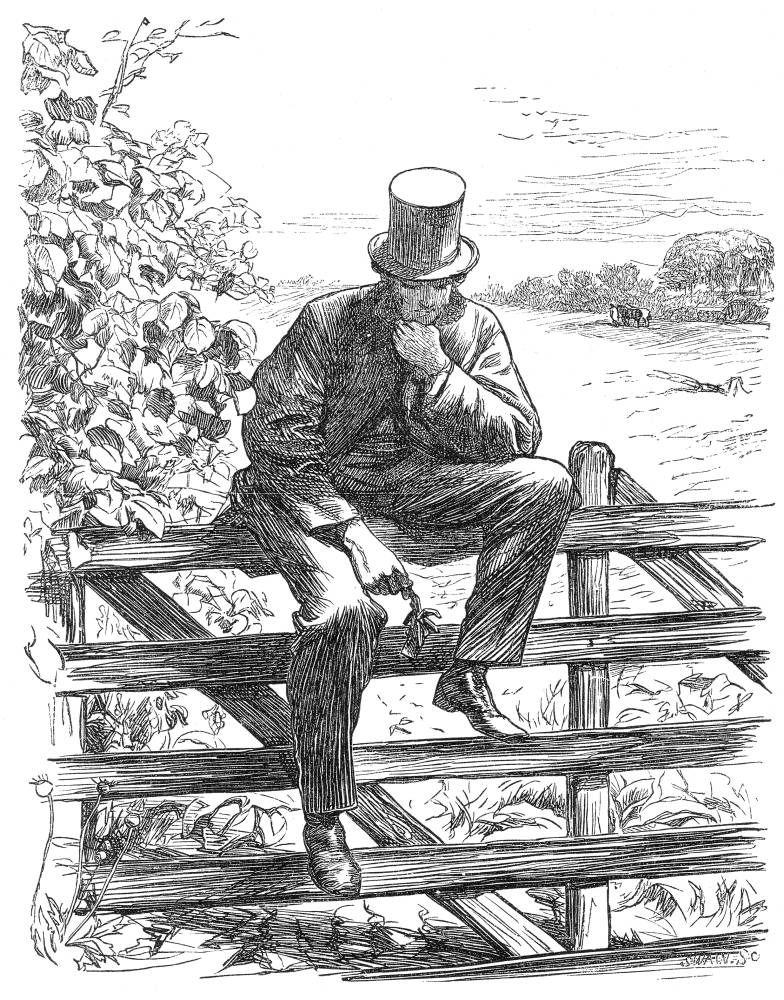

His visualization of Wood’s rapidly moving narrative seems on the face of it a conventional piece of prolepsis in which the opening design propels the viewer/reader forward, posing a question that demands to be answered by reading on. This is one of the central characteristics of Sensational illustration, a feature explored in detail by Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge. However, it is noticeable that Keene chooses scenes that are not necessarily the most significant in terms of moving the story forward; there is little of Wood’s sense of urgency and a clear avoidance of the climactic moments. The illustrator retains the basic units of dialogue between paired characters, but he repeatedly explores information which seems irrelevant. For example, in the second illustration he privileges a single line which notes how Lionel Verner had heard of Rachel’s death ‘in the village’ (7, p.71), and is equally oblique (in a fine piece of pastoral imagery) depicting a conversation with Robin (7, p.239). These illustrations visualize inference and listening rather than sharp exchanges; Wood’s novel is charged with the energy of dialogue and incident, but Keene transforms it into a more tenuous drama of interpretation.

Left to right: (a) [This scene shows the moment when rumours of Rachel’s death are circulating]. (b) [Robin discovered in the garden].

In so doing he necessarily emphasises moments of thought and deduction which slow the narrative. Instead of flurried crises of the sort pictured in his designs for A Good Fight, he visualizes quietude and reflection and makes the reader progress slowly from one weighted but ambiguous event to the next. The illustration of Frank’s contemplative day dream is a good example. Wood provides the bare bones of a style concerned with moving the story forward, noting only how he ‘sat perched on the gate of a ploughed field, softly whistling, His brain was busy, and he was holding counsel with himself’ (7, p.131). In the illustration, however, we have an image of intense inwardness; recalling Millais’s many images of rustic reflection, it compels the reader to engage with his state of mind in a way that the writing does not, and arrests the narrative in a single, poetic moment.

[Frederick in contemplation]

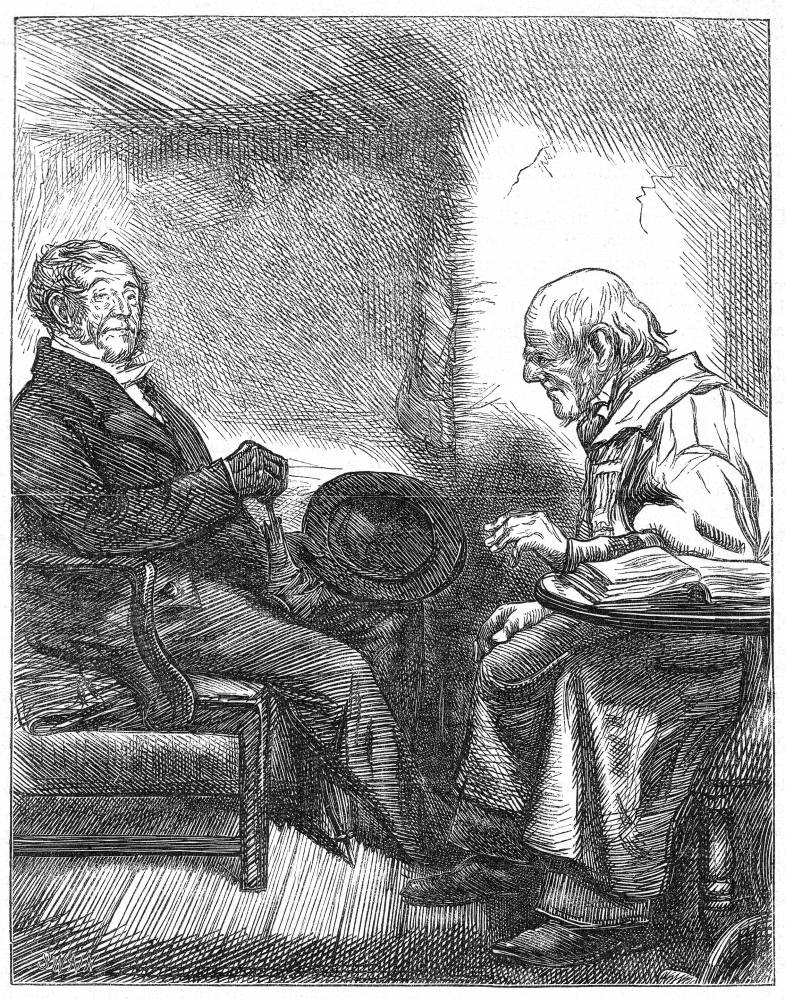

This slowing of pace and exploration of weighted moments has the effect of deepening the novel’s psychological effects. While not lacking in resonance, Wood’s characters are essentially the Sensational puppets of the story-telling; in Keene’s illustrations, on the other hand, the artist suggests a greater complexity. The emphasis on reflection notably deepens the characterization by showing the personae in moments of reverie, and in each case Keene adds subtle touches of implication and allusion. Lionel Verner is converted from a type into a more convincing individual and so is Robin. Wood describes him in the garden only as ‘sitting in a still attitude, his arms folded, his head bowed’ (7, p.242); yet when we look at the illustration we find Keene makes several important changes. Instead of depicting him with his arms folded, he shows him looking into space (7, p. 239); the conventional pose has been replaced with the greater psychological resonance of looking blankly at the world, while his face, detailed in the manner of Idyllic artists such as Frederick Walker, carries a weight of grief and despair. All of this is missing from the text. Keene constructs patterns of sympathy which are undeveloped in the story, and the artist amplifies his psychological effects as the series progresses. It is especially noticeable how Keene returns to the character of Robin when he is contemplating the site of Rachel’s suicide. Wood notes how ‘Lionel strode towards the figure and caught it by the arm’ (7, p.354), and it is only then that we realize its identity. However the illustration is more direct: the old man is shown as pathetically bent, his infirmity suggested by the curve of his outline, and we immediately realise his hopelessness. None of this is traditionally Sensational, and Keene ensures the slowed pace is matched by an expansion of the characters’ resonance.

Left to right: (a) [Robin discovered in the garden]. (b) [Lionel strode towards the figure and caught it by the arm]. (c) [Robin in conversation].

In this respect his strategies bear some relationship to Du Maurier’s interpretation of M.E. Braddon’s Eleanor’s Victory, which succeeded Verner’s Pride in 1863. As I have argued elsewhere, Du Maurier significantly deepens the characters in Braddon’s text, converting them from stage-types into plausible individuals. The same can be said of Keene’s approach, and by placing Verner’s Pride next to Eleanor’s Victory we can see a distinct pattern of ‘improving’ on the text. This may reflect Lucas’s intervention, even though he allowed other unreconstructed texts, such as The Notting Hill Mystery, to be extravagantly visualized in the manner of Grand Guignol.

Keene’s approach converts Wood’s excess into resonant psychological drama in which the characters are more than stock-types, but he adds other, enriching nuances as well. Critics of Wood have noted her interest in working class people, and Keene’s visualization richly develops this element. The author and artist are unity in the treatment of Rachel; Wood presents her in elegant terms, as a servant who is essentially a lady of delicate sensibility whom she describes as

A very beautiful girl. Her features were delicate, her complexion was fair as alabaster, with a mantling colour on her cheeks. But for the modest cap upon her head, a stranger might have puzzled to look upon her condition of life. She looked gentle and refined as any lady, and her manners and speech would not have destroyed the illusion. [7, p. 17]

This is strong material and Keene re-inscribes Wood’s signs in a powerful portrait in which he stresses her delicacy (signalled in the posture of her hands) and gentility (the down cast gaze, the beauty of her face). Moreover, Keene applies this sensitive approach throughout the text. Working with only textual clues, he represents Robin in convincing terms, and does the same for both the servants in the house and the yeomen who appear only peripherally. Sympathetic to the lower orders, Keene presents a re-reading of the text in which they seem very much a part of the fabric of middle-class life; Wood’s fiction, whatever Rachel’s part in it, is essentially a bourgeois tale, but the artist makes it seem far more democratic than the writing on its own seems to suggest. Robin, yeomen and the villagers appear in ten of the seventeen illustrations, and are emphasised far beyond their textual existence. This privileging of the commonplace is also developed in the showing of rural life which lies outside the enclosed spaces of troubled middle-class interiors. The village green (3, p.183), open fields (8, p.127; 7, p.127) and Robin’s garden (7, p.239) are all shown as evocative backdrops.

Left to right: (a) [Rachel observed by Frederick Massingbird]. (b) [A visual conclusion that focuses on ‘the company of all grades’ who welcome Lionel’s carriage.].

Pursuing a distinctly individual reading of his own, Keene changes and ameliorates the claustrophobic setting of Wood’s conventional tale, ventilating its action both literally – by opening up spaces around the characters – and socially, by showing their wider engagement with society. Wood’s characters, like those of all Sensational novelists, are essentially a social elite occupying a limited world of restricted action, moving from one interior to the next; Keene’s, conversely, seem relatively free to move within a larger physical world and a wider social milieu.

So Keene’s response to Wood is in many ways a piece of revisionism. Though tracing exciting events, he develops the characters and their situations. This approach underplays the Sensational elements and privileges the elements of domestic drama. What Keene does not do is show the novel as if it were a melodramatic play in the manner of Barnes’s designs for Reade’s Put Yourself in His Place (The Cornhill Magazine, 1869–70), or Huart’s illustrations for Braddon’s Dead Sea Fruit in Belgravia (1867–68).

Keene’s innovative series for Verner’s Pride, A Good Fight, and Evan Harrington might thus be viewed as fine examples of the sophistication of his style as well as his capacity to offer highly nuanced responses to a range of diverse texts. There is nothing formulaic in his treatments, and each is a sensitive and ingenious reading in which the writing is discovered afresh and interpreted anew. Though underrated, Keene is clearly an important illustrator of fiction and one who bears comparison with Millais, Leighton and Walker. More than anything else, he demonstrates once again how graphic art of the Sixties was as flexible a medium as the earlier styles of Cruikshank and Phiz.

Works cited and sources of information

Adams, Charles Warren]. ‘‘The Notting Hill Mystery.’ Once a Week (November 1862–January 1863). London: Bradbury & Evans, 1862–3.

Braddon, M.E ‘Dead Sea Fruit’Belgravia1867–68. Illustrated by Louis Huard.

Braddon, M.E. ‘Eleanor’s Victory.’ Once a Week (March–October 1863). Illustrated by George du Maurier. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1863.

Cooke, Simon. ‘George du Maurier’s Illustrations for M.E. Braddon’s Eleanor’s Victory in Once a Week.’ Victorian Periodicals Review 35:1 (Spring 2002): 89–106.

Cooke, Simon. Illustrated Periodicals of the 1860s: Contexts and Collaborations. Pinner: PLA; London: The British Library; Newcastle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2010.

Brothers Dalziel, The. A Record of Work, 1840–1890. 1901; new ed. London: Batsford, 1978.

Goldman, Paul. Victorian Illustration: the Pre-Raphaelites, the Idyllic School and the High Victorians. Aldershot: Scolar, 1996; new ed. London: Lund Humphries, 2004.

Hammerton, J.A. George Meredith: His Life and Art. London: Grant, 1911.

Houfe, Simon. The Work of Charles Samuel Keene. Aldershot: Scolar, 1995.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. The Artist as Critic: Bitextuality in Fin-de-Siècle Illustrated Books. Aldershot: Scolar, 1995.

Layard, G. S. The Life and Letters of Charles Samuel Keene. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co., 1892.

Leighton, Mary, and Surridge, Lisa. ‘The Plot Thickens: Towards a Narratology of Illustrated Serial Fiction in the 1860s.’ Victorian Studies 51:1 (2008): 65–101.

Muir, Percy. Victorian Illustration. London: Batsford, 1971.

Pennell, Joseph. Pen Drawing and Pen Draughtsmen. London: Macmillan, 1897.

Ray, Gordon. The Illustrator and the Book in England from 1790 to 1914. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 1976.

Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Eighteen Sixties. 1928; rpt. New York: Dover, 1975.

White, Gleeson. English Illustration: The Sixties, 1855 –70. London: Constable, 1897.

Wood, Mrs Henry [Ellen Price]. ‘Verner’s Pride.Once a Week 7–8 (28 June 1862 to 7 February 1863). Illustrated by Charles Keene.

Wood, Mrs Henry [Ellen Price]. Verner’s Pride. 3 vols. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1863. This, the first bound volume, was issued without Keene’s illustrations.

Last modified 12 May 2014