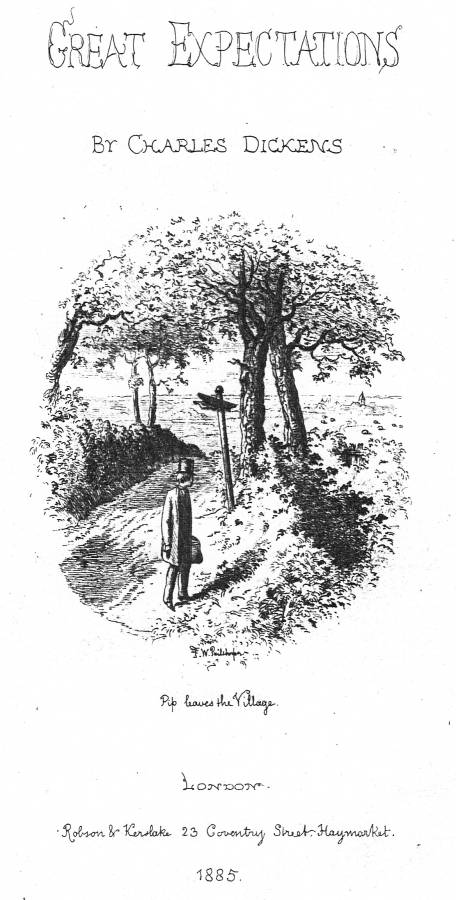

Frontispiece and vignette: Pip leaves the village hand-coloured lithograph for Charles Dickens's Great Expectations, first published as a black-and-white lithograph for the title-page of the Robson and Kerslake edition (1885), for Chapter XIX. 9 cm high by 7.8 cm wide (3 ½ by 3 inches). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Pip at the end of the "First Stage" bids farewell to the Village

I walked away at a good pace, thinking it was easier to go than I had supposed it would be, and reflecting that it would never have done to have had an old shoe thrown after the coach, in sight of all the High-street. I whistled and made nothing of going. But the village was very peaceful and quiet, and the light mists were solemnly rising, as if to show me the world, and I had been so innocent and little there, and all beyond was so unknown and great, that in a moment with a strong heave and sob I broke into tears. It was by the finger-post at the end of the village, and I laid my hand upon it, and said, "Good-bye O my dear, dear friend!"

Heaven knows we need never be ashamed of our tears, for they are rain upon the blinding dust of earth, overlying our hard hearts. I was better after I had cried, than before — more sorry, more aware of my own ingratitude, more gentle. If I had cried before, I should have had Joe with me then. ["The End of the First Stage of Pip's Expectations," Chapter XIX, pp. 174-175]

Commentary: Half-a-Century of Frontispieces and Title-page Vignettes for the Novel

Right: Phiz's title-page vignette for Martin Chuzzlewit (July 1844) likewise shows the hero setting out for the metropolis by stagecoach, and likely served as a model for Pailthorpe: At the Finger Post.

Writing in the tradition of Cervantes, Henry Fielding, and Sir Walter Scott through his first six novels, Charles Dickens deviated from the picaresque in that his protagonist, although something of an outsider, is never roguish or wilfully deceptive — nor is Pip undeveloped, for through his experiences he gains insights into human nature and into his own character that are not characteristic of the picaro. His progress is not merely physical, but moral and emotional, as he reacts with people of all social classes and conditions. The essentially good-hearted but somewhat obtuse Mr. Pickwick, accompanied by his own Sancho figure, the street-wise Cockney Sam Weller, may travel out from London, having misadventures on the high road, but he is no Jonathan Wilde. Nevertheless, the episodic structure, the high road being a metaphor for life as well as a literal highway from London to the provinces, inform novels as widely different as The Pickwick Papers and Martin Chuzzlewit. Pailthorpe, modelling his title page vignette on that for the latter novel, is pointing out one of the key elements of the picaresque form that occurs in Great Expectations, Pip's leaving the village on the marshes for the modern Babylon, the finger post and young traveller in Pip leaves the Village being directly modelled on Phiz's title-page vignette A New Pupil, but significantly Pip is departing rather than arriving and is utterly alone on the great road through the woods. The title-page vignette in the 1885 edition, then, shows Pip as similar to Dickens's earlier picaresque heroes, and yet unique, particularly in his narrative voice; and whereas Martin is a disinherited heir at the beginning of the story, a child of privilege, but his grandfather's heir at the close of the story, Pip is lower-middle class orphan at the beginning of the novel, elevated to education, social status, and significant "expectations" in the middle, and a disinherited clerk who must make his own fortune at the end of the book. Both young men, however, learn humility through suffering and must go abroad before finding themselves. Like the classic picaros that preceded him, Martin has a "street-wise" guide and companion, Mark Tapley, whereas Pip loses his moral compass and must learn again the value of labour from his virtuous brother-in-law.

Despite the fact that the Robson and Kerslake (London) edition was published late in the century, its illustrations are in an earlier, "caricatural" idiom well suited to the illustration of Dickens's earlier novels, from Pickwick to the Christmas Books of the 1840s. A great friend of the earlier Dickens illustrator George Cruikshank, Frederic William Pailthorpe (1838-1914) has deliberately composed his images in the satirical caricature tradition of Hablot Knight Browne. Although only in his early fifties at the time, Pailthorpe was of the "old school" of book and magazine illustrators, as represented by his inspirational friend Cruikshank, whose influence on Pailthorpe's work is obvious throughout the series on Great Expectations and that on Oliver Twist, although less obvious in the title-page vignette than that of Phiz (H. K. Browne).

Lost in the Thames fog, the village has but one salient characteristic, the church spire, pointing hopefully upward. The figure of Young Pip, although dressed very much in nineteenth-century fashion, recalls the many picaresque protagonists from eighteenth-century novels setting out on their journeys through life, from Fielding's Tom Jones to Smollett's Roderick Random, figures that Dickens knew so well from his childhood reading. Above the village, on the bench above the tidal marshes, the finger-post points directly away from all that Pip has ever known. But it is spring (as evidenced by the trees in full leaf) and the morning holds promise of a fair day ahead.

A Cavalcade of Innovative Frontispieces, 1860 through 1910

Left: John McLenan's uncaptioned headnote vignette, The Gibbet on the Marshes; left of centre, Marcus Stone's 1862 frontispiece With Estella after all. Centre: F. A. Fraser's untitled title-page vignette Pip approaching the lime-kiln, Ch. 35. Right: Charles Green's frontispiece, "With you — Hob and Nob," returned the Sergeant, and Harry Furniss's frontispiece, Pip fancies he sees Estella's Face in the Fire. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Left: John McLenan's uncaptioned headnote vignette, The Gibbet on the Marshes (24 November 1860) in Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization.

The initial illustrations in any nineteenth-century illustrated book, the frontispiece (usually realising a significant scene later in the narrative) and the title-page vignette, usually focussing on the protagonist (often without a physical background or social context) set up expectations in the reader which the text must immediately begin to address. The 24 November 1860 illustration in the Harper's Weekly serial serves as both frontispiece and vignette, establishing not merely the physical setting of the opening part of the story, the Kentish marshes and the village of Cooling, but also telegraphing to the alert reader the issues of region versus metropolis, and of crime and punishment that dominate the lives of such characters as Magwitch, Jaggers, and Compeyson — the gibbet being the standard means of summarily dealing with so many criminal offences in the eighteenth century. The practice of transportation, introduced in 1794 and not wholly abolished until 1853, was judged the more humane alternative to capital punishment. The initial illustration puts the reader on the Medway marshes towards sunset on a winter's evening, consistent with the December 1860 publication of the first four weekly instalments of the novel in All the Year Round, and of three of the first four instalments in Harper's Weekly.

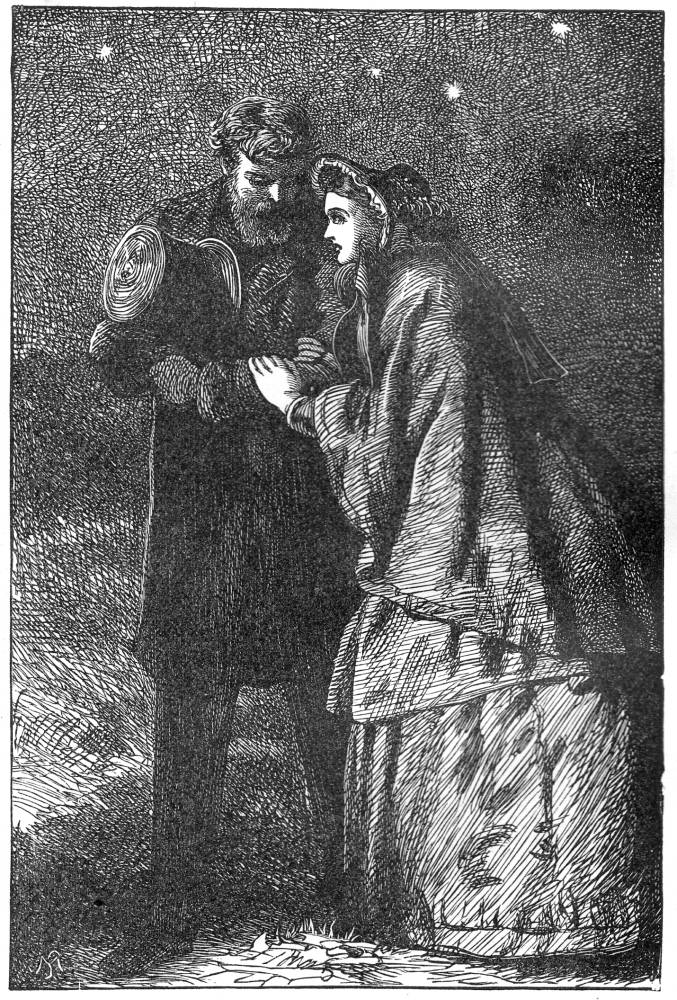

Right: Marcus Stone's 1862 frontispiece for the 1862 Illustrated Library Edition, With Estella after all.

Earlier editions place the emphasis elsewhere in the frontispiece and title-vignette. For instance, the frontispiece which Marcus Stone composed for The Library Edition (1862) at Dickens's own instigation after the completion of the serial run and the publication of the triple-decker in 1861, With Estella after all, focuses on the ultimate scene of the novel. Through this culminating dual portrait of the mature lovers Stone establishes the importance of the elements of romance in the story, and — most significantly — makes a compact with the reader at the very outset to resolve Pip's romantic dilemma in a manner satisfactory to both earnest protagonist and Victorian reader.

Left: F. A. Fraser's untitled title-page vignette Pip approaching the lime-kiln, Ch. 35.

Whereas the Household Edition's uncaptioned title-page vignette of Pip, much later in the novel, approaching the lime-kiln on the Marshes, demonstrates the protagonist's gullibility as he blithely walks into the snare which a vengeful Orlick has set for him, the facing frontispiece emphasizes Pip's uncomfortable relationship with Estella as he finds himself, a rank outsider in fashionable Richmond society, as part of a romantic triangle with Estella and Bentley Drummle. Thus, the opening illustrations of the Household Edition together characterise Pip's adult relationships, effectively juxtaposing the high society milieu imposed upon him by his expectations and the raw world of the village which he has never entirely put behind him.

Right: Charles Green's frontispiece, "With you — Hob and Nob," returned the Sergeant (lithograph, 1898).

The remaining frontispieces, by Green and Furniss, again set keynotes that the book immediately begins to elaborate upon: Green establishes the unexpected presence of soldiers and "Uncle" Pumblechook in Joe's forge, a scene realised in chapter five. more significantly, the scene implies that the party of soldiers will recapture the escaped felons and place them in the handcuffs whose locks Joe is about to repair. The military uniforms establish the setting as loosely within the era of the Regency and the Napoleonic wars, thereby implying that this is an historical novel that will transport the late Victorian reader back to the beginning of the century. And again the illustration involving the repair of the handcuffs prepares the reader for the novel's treating such matters as crime and punishment, the legal system, incarceration, and transportation of convicted felons.

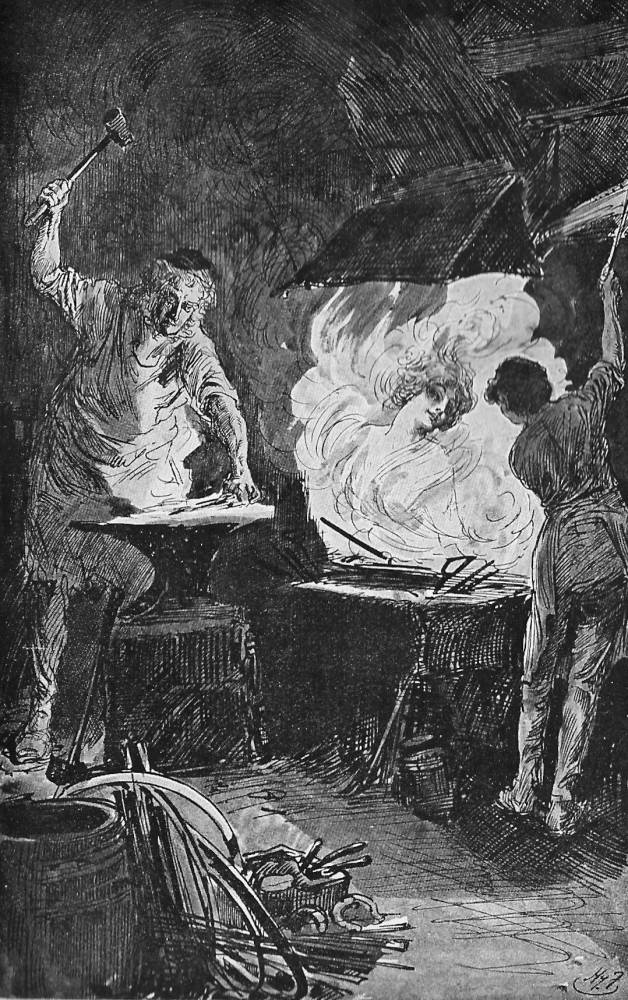

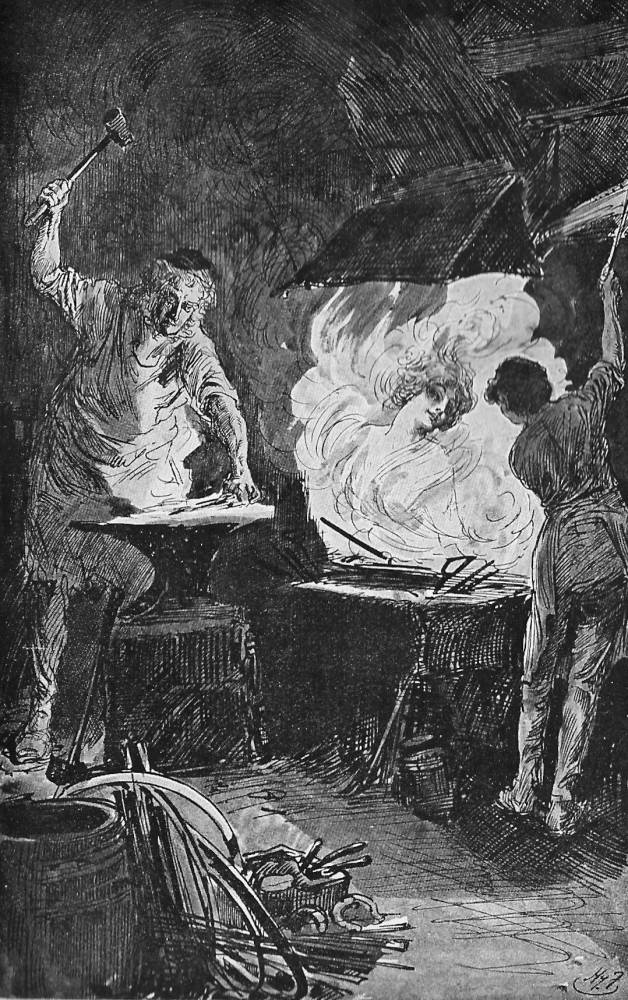

Left: Harry Furniss's frontispiece, Pip fancies he sees Estella's Face in the Fire (lithograph, 1910).

In contrast, although Furniss, too, sets his initial 1910 illustration in the forge, he uses this setting to juxtapose ironically Pip's identity as a blacksmith's apprentice with his romantic longings and aspiration to be elevated to gentlemanly status so that he will be worthy of the princess of Satis House, whose luxuriant form and feminine beauty he continually conjures up in the flames of the forge. Thus, Furniss establishes not merely Pip's unrealistic longings, but also his artistic imagination and sensitive nature, neither of which suit him for the vocation of blacksmith. In this juxtaposition Furniss may be alluding to such self-help narratives as Dinah Craik's 1856 John Halifax, Gentleman, an ironic title in that John Halifax, is an orphan growing up in the provincial town Norton Bury, in Gloucestershire, but determined to make his way in the world through honest hard work. He eventually achieves the success he desires, in both business and love, and becomes a pillar of the Victorian upper-middle class.

Related Material

- Dickens's Great Expectations in Film and Television, 1917-2000

- Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations

- Bibliography of works relevant to illustrations of Great Expectations

Other Artists’ Illustrations for Dickens's Great Expectations

- Edward Ardizzone (2 plates selected)

- H. M. Brock (8 lithographs)

- J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd") (2 lithographs from watercolours)

- Felix O. C. Darley (4 photogravure plates)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (8 wood engravings)

- Marcus Stone (8 wood engravings)

- John McLenan (40 wood engravings)

- F. A. Fraser in the Household Edition (29 wood engravings)

- Harry Furniss (28 plates)

- Charles Green (10 lithographs)

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "The Illustrations for Great Expectations in Harper's Weekly (1860-61) and in the Illustrated Library Edition (1862) — 'Reading by the Light of Illustration'." Dickens Studies Annual, Vol. 40 (2009): 113-169.

_____. Great Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. XIII.

_____. Great Expectations. Illustrated by F. A. Fraser. Volume 6 of the Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876.

_____. Great Expectations. Illustrated by F. W. Pailthorpe. London: Robson & Kerslake, 23 Coventry Street, Haymarket, 1885.

_____. Great Expectations. Illustrated by H. M. Brock. Imperial Edition. 16 vols. London: Gresham Publishing Company [34 Southampton Street, The Strand, London], 1901-3.

_____. Great Expectations. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. XIV.

_____. Great Expectations. Illustrated by Frederic W. Pailthorpe with 17 hand-tinted water-colour lithographs. The Franklin Library. Franklin Center, Pennsylvania: 1979. Based on the Robson and Kerslake (London) edition, 1885.

Harmon, William, and C. Hugh Holman. "Picaresque Novel." A Handbook to Literature. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2000. Pp. 389-390.

Paroissien, David. The Companion to "Great Expectations." Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 2000.

Created 21 January 2014 Last modified 28 October 2021