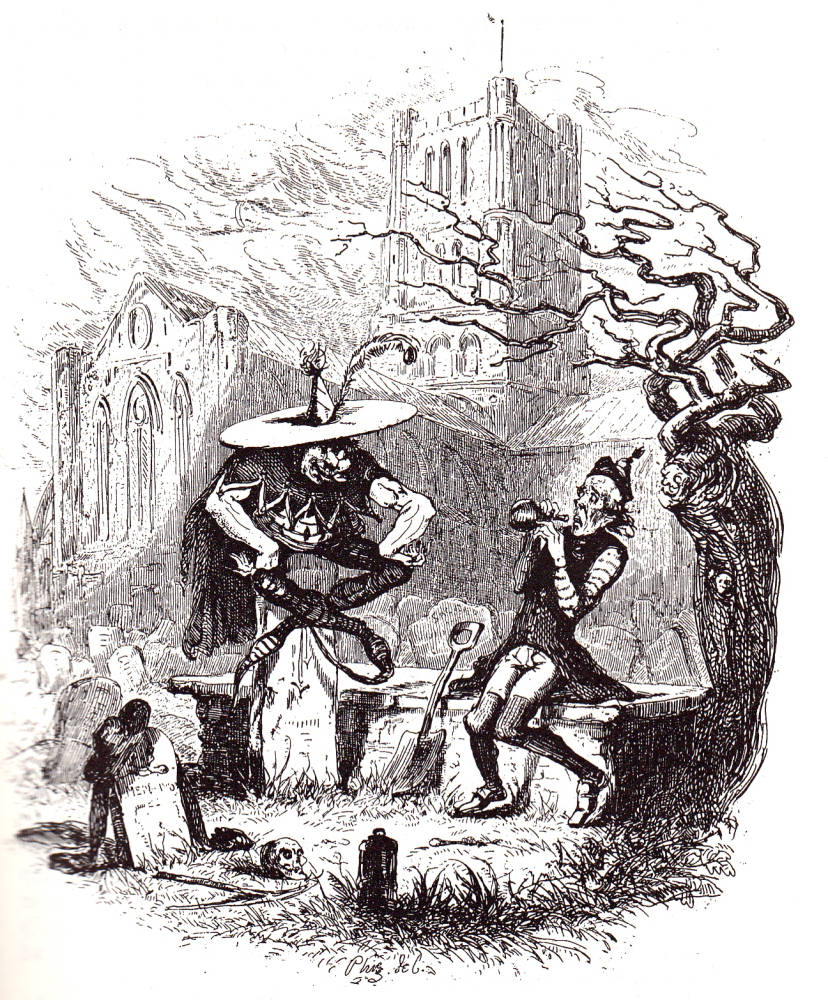

he tenth instalment of The Pickwick Papers (31 December 1836) had contained as 'a

good-humoured Christmas Chapter' (XXVIII), "The Story of the Goblins who stole a

Sexton." The tale's protagonist, the solitary, old bachelor-curmudgeon, the grave-digger

Gabriel Grub, is the prototype of Ebenezer Scrooge. The visions and the beatings which

the goblin king and his constantly smiling courtiers deliver serve to reintegrate the

misanthropic Grub socially and restore him into a state of charity with the rest of

humanity. This inset tale bears some obvious points of resemblance to A Christmas Carol, written seven years later.

he tenth instalment of The Pickwick Papers (31 December 1836) had contained as 'a

good-humoured Christmas Chapter' (XXVIII), "The Story of the Goblins who stole a

Sexton." The tale's protagonist, the solitary, old bachelor-curmudgeon, the grave-digger

Gabriel Grub, is the prototype of Ebenezer Scrooge. The visions and the beatings which

the goblin king and his constantly smiling courtiers deliver serve to reintegrate the

misanthropic Grub socially and restore him into a state of charity with the rest of

humanity. This inset tale bears some obvious points of resemblance to A Christmas Carol, written seven years later.

Right: The original Phiz steel-engraving for the Christmas ghost story in the January 1837 (tenth) part of Pickwick, The Goblin and the Sexton, Chapter 29.

Although he had always venerated Christmas, Dickens did not consider writing another such story using the seasonal setting until 5 October 1843. Invited to speak at the first annual general meeting of the Manchester Athenaeum (an adult education institute for the working class of that highly industrialised city), Dickens had stayed with his beloved older sister Fan (now Mrs. Henry Burnett), one of whose two young sons was a frail cripple. The prototype of Tiny Tim (in the initial draft named "Fred," after Dickens' younger brother) died early in 1849, following the death of his mother on 2 September, 1848 (when Dickens was at work on the last of the Christmas Books). Sharing the speakers' platform with the notable politicians Benjamin Disraeli and William Cobden, Dickens alluded in his address to the Ragged Schools, self-help institutions for the urban poor that Dickens was encouraging his friend, the banking heiress and millionaire-philanthropist Miss Angela Burdett-Coutts, to support.

These elements — the "Condition of England" Question, the Ragged Schools, the Manchester Athenaeum, Dickens' first-hand experiences with industrialism and prisons on his recent American reading tour, the need for reconciliation between the working and governing classes — combined with Dickens' pressing need for extra income and recent recollections about his childhood at No. 16 Bayham Street, Camden Town (including the unseasonably cold Christmases of 1812-1820), form the background of the first Christmas Book. Beginning on the 13th of October after his return from the Midlands, Dickens finished the novella in six weeks.

Ironically, this, one of the best loved stories in the English language, at first lost the author money, for his income on sales of the first 6,000 copies was but £230 while costs he incurred in suing Peter Parley's Illuminated Library for pirating the Carol amounted to £700 when the malefactors declared bankruptcy. Ackroyd in Dickens (1990) speculates that it was Dickens' Pyrrhic victory in the Carol suit that produced his loathing and disgust for the legal system. The matter of profits from the sale of what was undoubtedly one of the most successful publications to date brings us to a consideration of the role of the writer and the modes of commercial publication available to the writer in the 1840s. Here are some significant facts about what a reader might pay in that decade:

- Triple-decker novel Jane Eyre (1847): one-and-a-half guineas;

- One 32-page instalment of Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-4): one shilling (19 parts as 20, the last a double number = one pound);

- A six-part novel in Fraser's Monthly Magazine at half-a-crown a number: fifteen shillings total;

- A Christmas Carol in five "staves" (chapters): five shillings.

Dickens was very particular about producing a high-quality, reasonably-priced product for the Christmas book trade. The slender volume was bound in red cloth, with a gilt design on the front board and spine, and edges trimmed and gilt. Sixty per cent of the cost was incurred in the binding and the hand-tinting of four of the eight plates by Punch magazine artist John Leech. Only sixteen per cent of the costs of the book involved the actual printing. By the close of 1844 the book had sold almost 15,000 copies — but at a profit to Dickens of only £726. In contrast, Dickens received £200 for each instalment of the nineteenth monthly instalments of Martin Chuzzlewit and three-quarters of the profits on monthly sales averaging 20,000 a number (and never rising above 23,000).

The Structure and Theme of A Christmas Carol(1843)

Over the course of a single Christmas Eve (1842?), Ebenezer Scrooge (who has absorbed not only his dead partner Jacob Marley's possessions but also his identity over the seven years since Marley's death) re-lives five incidents from his past, visits scenes from the present Christmas to Twelfth Night, then is given a pre-vision of a potential future which connects his own death to that of the child of his poor clerk, Bob Cratchit. Whereas Marley is a Germanic geist (human spirit), the three Christmas spirits are genii. In the spiritual dimension human time stands still (the spirits accomplish all their revelations in one night, not three or four as it first seems to Scrooge) or is restructured so that Scrooge can see himself as child, youth, and mature man of business in breath-taking succession. Edgar Johnson has identified the three Christmas spirits as personifications of memory, example, and fear. As with the British dramatisations of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, the name of the actor who played the monstrous and terrifying agent of the protagonist's doom was designated in playbills and published scripts as * * * * * *.

Michael Slater in his preface to the Penguin two-volume Penguin edition of The Christmas Books (1971) has proposed that all the works in the series, as products of the Hungry Forties, share seasonal settings, supernatural agents, and spiritual conversions, along with a special intimacy of tone and colloquial style not found in Dickens' big novels. The five novellas suggest a common motif of familial love and the beneficial effect of memory on the moral life. Although The Christmas Books are interesting as full-scale novels in embryo, the general critical opinion of them is epitomized by Steven Marcus's comment in Dickens from Pickwick to Dombey (1965), which describes Dickens's Christmas Books as "minor fictional works" (272) of the 1840s. He feels that "The first of these, A Christmas Carol, is the only one of genuine literary interest" (272).

The final scene of A Christmas Carol, in Scrooge's office on the day after Christmas, recapitulates the novella's chief themes. Bob is physically "behind his time" (as Scrooge has been spiritually), but instead of threatening him with termination or reduction in wages Scrooge raises his salary (the respectable, middle-class term for "wages") and offers to help Bob raise his family, especially Tiny Tim. The words "and to Tiny Tim, who did Not die, he was a second father" do not appear in the Carol manuscript (now in the Pierpont Morgan Library); these Dickens must have added in proof. The line told to great effect on Dickens' first public audience of 2,500 on 28 December 1853 at Birmingham Town Hall, and the following year on an audience of 3,700 at Bradford's Educational Temperance Institute. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph for 11 December, 1855, reports that the whole assembly rose spontaneously on that line to cheer Dickens. Truly A Christmas Carol had become over those fourteen Christmasses, as the rival novelist William Makepeace Thackeray had remarked, "a national benefit."

Related Materials

- The Christmas Books by Charles Dickens, 1843-1848

- Dickens — "The man who invented Christmas"

- An Introduction to A Christmas Carol

- Dickens's Childhood Experiences and A Christmas Carol — An Introduction with Discussion Questions

- Sympathy and the Spirit of Capitalism in Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- Ebenezer Scrooge to the Charity Collectors — "Are There No Prisons . . . Are There No Workhouses?"

- Scrooge

- Sympathy for the Poor and Christmas Present — An Introduction with Discussion Questions

- Sentimentality: The Victorian Failing

- Two Contemporary Responses in The Illustrated London News

- Washington Irving and Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- Vocabulary Notes for A Christmas Carol

- Recent editions particularly useful for students and scholars

- Recent editions particularly useful for students and scholars

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Allingham, Philip V. "The Naming of Names in Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol." Dickens Quarterly 4:1 (1987): 15-20.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol in The Christmas Books, 2 vols., ed. Michael Slater. Illustrated by John Leech. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1993. Vol. II: pp. 33-134.

Johnson, Edgar. Charles Dickens: His Tragedy and Triumph. 2 vols. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1952; i vol., revised and abridged, New York: Viking, 1977.

Marcus, Stephen. Dickens from Pickwick to Dombey. New York: Clarion; Simon and Schuster, 1965.

Patten, Robert L. Dickens, Death, and Christmas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023. 344 pages. ISBN 978-0-19-286266-2. [Review]

Slater, Michael. "Introduction to A Christmas Carol." The Christmas Books, 2 vols. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978. Vol. 1, 33-36.

Thomas, Deborah A. Chapter 4, "The Chord of the Christmas Season." Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982, 62-93.

Created 28 February 2003 Last modified 23 August 2024