This an extended and updated excerpt from a more widely-ranging article, "Girls' Education and the Crisis of the Heroine in Victorian Fiction," originally published in English Studies, Vol. 75 (1), January 1994: 34-45. The images are from Vols. I and II of the Illustrated Cabinet Edition of the novel published in Boston by Dana Estes & Co., c.1900, uploaded to the Internet Archive by the University of California Libraries. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on the images for larger pictures.]

exing no less than vexed, Maggie Tulliver in The Mill on the Floss, is widely taken as the most autobiographical of George Eliot's heroines, and with good reason. "That little girl" (54) growing up at Dorlcote Mill near the town of St Ogg's, with her elder brother Tom, is clearly the focus for authorial reminiscence in the first brief chapter. The two children here were even born in the same years as Eliot and her brother Isaac (see Haight 5). Moreover, Eliot's involvement with her heroine's childhood is implicit in her admission to her publisher that "my love of the childhood scenes made me linger over them" (Letters 3: 374). But the old question of how far the novelist's characters were modelled from life is as pertinent here as elsewhere, and must be given the same answer. Maggie is not her author, but rather, as Rosemary Ashton says of a very different character, Casaubon in Middlemarch, a "compound of George Eliot's self-knowledge, self-criticism, elements from other difficult temperaments with which she was acquainted, and material fresh from her own mint" (15). In particular, Maggie differs from her creator in continuing to suffer from the inadequate challenging and directing of a keen mind. Uncountered, this deprivation is perhaps the single most important factor in the memorably tragic outcome.

exing no less than vexed, Maggie Tulliver in The Mill on the Floss, is widely taken as the most autobiographical of George Eliot's heroines, and with good reason. "That little girl" (54) growing up at Dorlcote Mill near the town of St Ogg's, with her elder brother Tom, is clearly the focus for authorial reminiscence in the first brief chapter. The two children here were even born in the same years as Eliot and her brother Isaac (see Haight 5). Moreover, Eliot's involvement with her heroine's childhood is implicit in her admission to her publisher that "my love of the childhood scenes made me linger over them" (Letters 3: 374). But the old question of how far the novelist's characters were modelled from life is as pertinent here as elsewhere, and must be given the same answer. Maggie is not her author, but rather, as Rosemary Ashton says of a very different character, Casaubon in Middlemarch, a "compound of George Eliot's self-knowledge, self-criticism, elements from other difficult temperaments with which she was acquainted, and material fresh from her own mint" (15). In particular, Maggie differs from her creator in continuing to suffer from the inadequate challenging and directing of a keen mind. Uncountered, this deprivation is perhaps the single most important factor in the memorably tragic outcome.

Girlhood

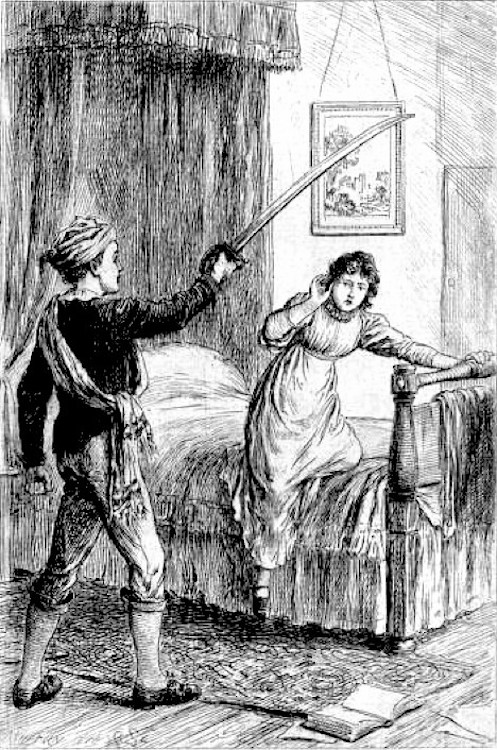

Right: "Tom frightening Maggie," an original (and telling) etching by C. O. Murray. Illustrated Cabinet ed., I: 254. Tom is just showing off here, and pretending to be the Duke of Wellington. But, says Maggie later, "You have always been hard and cruel to me, even when I was a little girl" (450).

Maggie's intelligence is never considered an asset. Her early facility in reading provokes a mixture of pride and anxiety in her father, and admonition and patronage in the auctioneer, Mr Riley. When she talks to the latter about the book she is poring over (which happens to be an illustrated edition of Defoe's History of the Devil), and explains that it concerns the drowning of a poor woman suspected of being a witch, he views her with as much suspicion as if she were the victim herself. As many have noted, the subject matter here gives an early indication of the role of Maggie's reading material in the text. From this point onwards, such books not only give us insight into her character, but "develop themes, and foreshadow the plot" (Golden 80). But what stands out at first is mainly the precociousness of her reading, and how her elders react to it. "Too 'cute for a woman" (59-60) admits her father, even though the "straight black-eyed wench" is so dear to him (60). She can expect no encouragement from the Tullivers in this area, then; no direction as to choice of subjects, or discussion of the ideas that she encounters. Her father had, in fact, bought Defoe's book in a job lot, which he judged by the binding; her mother, soon to be described as "from the cradle upwards ... healthy, fair, plump, and dull-witted" (62), believes that her daughter's "'cuteness ... all runs to naughtiness" (60)

The situation never improves. The Rev. Walter Stelling, her brother Tom's tutor, disparages the growing girl's aspirations with astonishing bluntness. When the ten-year-old asks him, "couldn't I do Euclid, and all Tom's lessons, if you were to teach me instead of him?" she gets notoriously short shrift from both males, young and old:

"No; you couldn't," said Tom indignantly. "Girls can't do Euclid; can they, sir?"

"They can pick up a little of everything, I daresay," said Mr Stelling. "They've a great deal of superficial cleverness: but they couldn't go far into anything. They're quick and shallow." [220-21]

If not unopposed, this conception of the female intellect was nonetheless current throughout the nineteenth century: "the biological model" was applied not only to their reading (see Golden 79) but to their mental powers in general. At the very beginning of the Victorian period, an advocate of co-educational pauper training condescendingly suggested that girls' "quick perception" could serve as a sort of spur to the "stronger minds" of boys (Fourth Annual Report, 298). Decades later, the situation had changed little. George Meredith, himself a keen promoter of women's rights, has young Crossjay in The Egoist (1879) say tauntingly about girls, "[t]hey're flash-in-the-pans" (58). In other words, the powers that be (men) were still growing up with the idea that something in girls' very make-up meant that, whatever their capacity to aspire and even inspire, they could neither go deeply into their studies nor (literally) stay the course.

The sad result of such an ingrained expectation in The Mill on the Floss is that while a boy like Tom Tulliver, who dislikes reading, goes to be educated as a "scholard" (65) and is still stumbling through his lessons at sixteen, his sister, who lives in her books, spends a year at the local school in St Ogg's and is so starved of reading matter at home that she is sometimes driven to read the dictionary (176). Her doubtful advantage of a spell at a girls' boarding school with her "pink-and-white" cousin Lucy Deane (164) is then cut short by her father's financial ruin in his ill-advised law suit, and stroke, when she is still only thirteen. Maggie's experiences at Miss Furniss's establishment in Laceham teach her to greet Tom's old schoolfellow Philip Wakem in the street with due propriety (263). But, when she turns over some of her old schoolbooks from Laceham later, she feels dissatisfied, recalling that even at the time "she had often wished for books with more in them: everything she learned there seemed like the ends of long threads that snapped immediately" (379). The sewing metaphor is significant. Maggie's formal education (no Euclid here, of course; and nothing to offer her "effectual wisdom," 380) has not taken her much beyond the training at patchwork to which her mother had once put her.

Ironically enough, Tom's own education proves totally unsuitable for the role into which he is quickly thrust by his father's losses. Mr Tulliver thought right from the start that Mr Stelling would be "a'most too high-learnt to bring up a lad to be a man o' business" (72), and when Tom goes to his uncle Deane (Lucy's father) for help in finding a job, he confirms it. His "good eddication" (347), as his father calls it, counts for nothing, and he has to attend evening lessons in more appropriate subjects: "book-keeping and calculation" (331). The point is not that young people should all study Euclid, logic and the classics but that they should all be educated according to their gifts and needs.

Young Womanhood

Left: "Maggie and Lucy," a photo-etching from a drawing by W. St John Harper. Illustrated Cabinet ed., II: frontispiece. Sweet-natured Lucy is the perfect foil to Maggie, who is the very type of the "dark-haired, demonstrative, rebellious girl" (85). Maggie pushes her into the mud once as a child, but is fond of her all the same: "Maggie always looked at Lucy with delight" (117). She will look up at her again with great feeling on their last meeting: "Lucy never forgot that look" (643).

With such a background as hers, the heroine's frustration can only increase. Later, in a setting that reminds us of the first nightmarish window episode in Wuthering Heights, Maggie ("Poor child!" still, and "as lonely in her trouble as if she had been the only girl in the civilised world of that day") is filled with a "wide hopeless yearning," and longs desperately for the kind guidance she has never had — that of "elder minds" (381). Her window ledge, like the one in Catherine Linton's old room at Wuthering Heights, has books on it, and she picks up from it the shabby old volume of Thomas à Kempis's Imitation of Christ, which suggests to her a way out of "all the miseries of her young life" (384) — renunciation of the self. Inspired by this one book, the untutored girl now embarks on the deliberate starving of her mind, rejecting Philip Wakem's offer to lend her a copy of Sir Walter Scott's The Pirate, on the grounds that "it would make me long to see and know many things — it would make me long for a full life" (402). Such an ambition was exactly what the opponents of girls' education feared, less because they thought their dream of expanding their intellectual horizons biologically doomed anyway, than because they felt that the pursuit of it would rob women of their "maidenly modesty" (England's Daughters, 9). Maggie, it seems, has now taken on board society's suffocatingly narrow expectations.

Though Maggie then accepts Philip as her mentor for almost a year, meeting him clandestinely in the Red Deeps, his influence is limited. The only book we see actually passing between them is Corinne, which he expects (with some trepidation) that Maggie will be inspired by, but which she stops reading, again because of her personal frustrations. Her cri de coeur is as notorious among commentators on the novel as Mr Stelling's put-down: "I've determined to read no more books where the blond-haired women [conventional and compliant beauties] carry away all the happiness" (433). Corinne may not have been the ideal model for Maggie, but this intellectual Amazon gave the impetus to many gifted girls of the nineteenth century, including, for example, Elizabeth Barrett Browning (see Moers 174, 177). Thus denial is compounded by self-denial, and Maggie's sense of being painfully thwarted, the fate of so many other heroines in Victorian fiction, continues to vitiate her intellectual development. The repercussions are devastating: a young girl who, as Philip recognised, held the promise of turning into a brilliant woman, is finally (and again, it must be remembered, quite unlike Eliot herself) unable to find her footing in the world.

What makes this so sad is that Maggie does try to establish herself in it. When we meet her again after Mr Tulliver's death, we learn that for nearly two years she has maintained her independence by teaching little girls in a "third rate schoolroom" (494) at a school reminiscent of Jane Eyre's Lowood, where she has had to mend the children's dresses, and eat watered-down rice-pudding. Now she wants to improve herself. Just before her first encounter with Stephen Guest, the young man whom Lucy expects to marry, she tells her cousin that she is saving up for lessons. What she has in mind is not the kind of tuition calculated to expand her intellect, broaden her mind, give her self-belief and enable her to lead the kind of life she had once set her heart on. But it would at least give her enough "accomplishments" to find "a better situation" (481). This would be something.

At the same time, however, and despite putting money by, Maggie seems to be losing heart. She admits to Lucy:

It is with me as I used to think it would be with, the poor uneasy white bear I saw at the show. I thought he must have got so stupid with the habit of turning backward and forward in that narrow space that he would keep doing it if they set him free. One gets a bad habit of being unhappy. [481]

The image speaks directly to modern sympathies, and suggests that Maggie cannot see any real possibility of change or escape. The caged creature's plight is being subtly internalised. In fact, the very day before the ball at which Stephen shows his feelings for her, Maggie tells Lucy that she is returning to the treadmill. She has accepted the offer of their old teacher Miss Firniss, to take three of her present orphaned charges to the coast in the holidays. She will then try out as a teacher with her. If not the "menial" position that her aunt, Mrs Pullet, calls it later (575), this is still most unworthy of the intelligent Maggie. But her options are so limited. Aunt Pullet herself, a hypochondriac much concerned with dressing in the height of fashion, thinks her niece would be better employed as her companion, and doing her sewing for her — provided, of course, "she wasn't wanted at her brother's." The eldest of Mrs Tulliver's sisters, Maggie's demanding aunt Glegg, deplores Maggie's leaving too, since she had "laid caps out on purpose for her to make 'em up" (575-76). Such were the prospects of a dependent woman within the family.

The Tragic Outcome

Right: "Maggie Tulliver in the boat," a photo-etching from a drawing by F. S. Church. Illustrated Cabinet ed., II: 355. In "The Final Rescue," Maggie's black hair is streaming, and Tom sees her in the boat opposite him "with eyes of intense life looking out from a weary, beaten face" (654).

Maggie's schooling, such as it was, has left her not only without adequate attainments, but, worse, with

a soul untrained for inevitable struggles ... with much futile information about Saxon and other kings of doubtful example, but unhappily quite without that knowledge of the irreversible laws within and without her which, governing the habits, becomes morality, and developing the feelings of submission and dependence, becomes religion.... [381]

Simply not equipped to forge her own way in life, she is now "made half helpless" in another way — this time by her attraction to Stephen (586). When circumstances conspire for the pair to take a boat trip together to nearby Luckreth, Stephen's "stronger presence" seems "to bear her along without any act of her own will" (588). Not only Maggie's will, but her memory and her very consciousness of her surroundings are lost, and she suffers the "fits of absence" to which she has been liable since childhood (589). Once she realises that Stephen has rowed on past Luckreth, she blames him, but also herself: "She had reproached him for being hurried into irrevocable trespass — she, who had been so weak herself" (591). However, even while knowing that she should have avoided this situation, she lacks the strength and confidence to take control of it. Again she gives way, and allows Stephen to carry her on, so that the pair spend the night together on the poop bearing them to Mudport, as the first stage, Stephen hopes, of an elopement.

However innocently spent, this night makes matters far worse. Maggie has now lost any chance of putting things right with Lucy, or indeed with Philip, who had thought that only Tom's hostility was preventing them from marrying. Awakening in the early hours, Maggie herself realises that "[t]he irrevocable wrong that must blot out her life had been committed — she had brought sorrow into the lives of others — into the lives that were knit up with hers by trust and love" (597). Only now does she gather the resolve to return alone. Things may yet improve for Lucy and Stephen; and Tom is so implacable, so much the stern father figure now (see Sadoff 85), that Philip might never have won Maggie. It is Maggie herself who is worst affected. Her reputation is well and truly lost. The repetition of the word "irrevocable" sounds the note of doom for her; her life, impossibly limited as it was before, is about to become even more unbearable.

Book Seventh of the novel, "The Final Rescue," traces Maggie's last futile efforts to find a role for herself in St Ogg's under the protection of the kindly Rector, Dr Kenn. But these efforts come to nothing. She is now overwhelmed by a debilitating fear of her own weakness. Even if she made a fresh start in life, away from the gossips of St Ogg's, would she not simply "struggle and fall and repent again"? She is filled with something worse than despair — "self-despair" (649). Yet when the flood rushes into Bob Jakin's house, where she has found shelter, she acts decisively. Having woken Bob, she manages to reach Dorlcote Mill by boat, towards the end with a new "sensation of strength" (652). Here, she summons Tom from the mill which is already partially engulfed in water. Maggie therefore initiates the final reunion with her previously censorious brother, restoring him to a state of childhood innocence before bulky fragments of machinery loosed from a wharf bear down on them and consign them together to a watery grave. The euphoria of that one "supreme moment" together (655) must be offset by the sheer irony of Maggie's having again found the power to act only when it is already too late, at least for happiness in this world. Moreover, it is hard to see this reunion as involving what it most obviously purports to involve: a joyful return to an idyllic brother-and-sister relationship. As Kathryn Hughes rightly reminds us, such a relationship had hardly existed in the first place (227).

To many, this cataclysmic ending represents the author's own submission to the fantasy of an eternal brotherly embrace: "Maggie's powers and frustrations have less to do with Tom for us than for George Eliot" (Byatt 39). It is well known that Eliot's rejection by her brother Isaac, who disapproved of her relationship with G. H. Lewes, had hurt her deeply. But such a reading again stems from too close an identification of the heroine with her creator. Among the most convincingly argued interpretations are Elizabeth Ermarth's, that Maggie's death is the last act in (to use Philip's words on an earlier occasion) her "long suicide" of self-denial (429); and Paul Yeoh's, that Maggie's "genuine impulse" to renounce the self (5) leads to what is, in effect, a modern form of martyrdom, in which she redeems her brother as well as herself. As for the latter, Tom himself senses in her arrival at the flooded mill "a story of almost miraculous, divinely-protected effort" (654). These readings need not be mutually exclusive. When Maggie is reprimanded by her brother for her first indiscretion, her meetings with Philip in the Red Deeps, she responds, "you are a man, Tom, and have power, and can do something in the world" (450). She has not been able to "do something in the world," and, turning in on herself, has found an alternative in self-renunciation, tending towards both masochism and (more positively) martyrdom.

There is certainly more to this novel than "a negative critique of disabling social categories" (Yeoh 19). Eliot was evidently influenced by the ideas of Darwin, and more specifically of her close friend Herbert Spencer (see Byatt 22), and nature as well as nurture plays a part in Maggie's fate. The unruly girl clearly inherits her father's contrariness together with the Tulliver colouring; like her aunt Moss on her father's side, she might always have been "too impulsive to be prudent" (304-05). Yet Maggie's very inadequate education, intended only to fit her for "the woman's situation with its enforced passivity and pathos, and the stifling of the individual by artificial social roles" (King 78), must be considered a major determinant of the tragedy. As well as vitiating her intellectual potential and preventing her from finding a role in life commensurate with it, it hampers her ability to govern herself, and to deal in a timely fashion with the particular problems that come her way.

The Literary Context

Left: An upward-looking George Eliot, as shown on the Illustrated Cabinet Edition binding, picked out in gold against the deep olive green of the cover.

The schools that Eliot herself attended in Nuneaton and Coventry should not be dismissed as "of the dames' schools variety" (Fleishman 5). She was much influenced by the Evangelical Maria Lewis at Miss Wallington's in Nuneaton, where about thirty girls boarded (Cross 15), and Rebecca Franklin of the Miss Franklins' boarding-school in Coventry was reported to be "a lady of considerable intellectual power" (Cross 18). It was, however, "a typical middle-class girls' education" (Fleishman 11), and she had to make her own efforts to add Latin, Greek, some Hebrew, and other modern languages to her French and German; also to build on her history, and study philosophy and the sciences. She continued to deplore girls' narrow educational opportunities in her later novels. At Mrs Lemon's in Middlemarch, described as "the chief school in the county" (123), Rosamond Vincy learns how to play the piano to great effect, embroider, sketch, get in and out of carriages properly, and so on; Dorothea, tutored both in England and Lausanne, has fared little better with that "toy-box history of the world adapted to young ladies which had made the chief part of her education" (112). Both these young women suffer as a result, Rosamond's husband, however, more than she does — a danger Mary Wollstonecraft had warned men of in the last century, in A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792). All the same, it is Maggie Tulliver who suffers most dramatically of all. However we read it, her final escape from her trials evokes a real sense of waste. For some ills, as the author warns in her own conclusion, "there is no thorough repair" (656).

Vituperation rather than guidance is offered to "difficult" (that is, intelligent) young girls in the works of other Victorian novelists; cruel and unusual punishments are regularly meted out to older ones who want something more than to conform to the expected pattern. Their wits have to be blunted, subdued; their ambitions and their very identities crushed. Not every heroine has the guts of a Catherine Linton or a Jane Eyre, to resist such onslaughts herself; fewer still go on, like Jane, to develop their own abilities, self-belief, and independence. Most are left to struggle with their disability, effectively disempowered for life — in every sense. One of Maggie's predecessors is Louisa Gradgrind/Bounderby in Dickens's Hard Times (1854), whose schooling is inadequate in a different way from hers, having been based only upon facts. An "intelligent sister" with "nothing to fall back upon" (122), she too has a close sibling attachment to a brother called Tom, and experiences a "Great Temptation" by an unsuitable man — in her case, the rakish James Harthouse. For Louisa too there is no conventionally happy ending: "Such a thing was never to be" (267). In 1853 Dickens sent his own daughter Katey to the recently founded Bedford College, London, where she learnt to become "an accomplished painter" (Tomalin 247). In the last paragraph of his novel he looks up from the page, as it were, and appeals directly to his readers. It is up to us, he implies, to ensure that children are not blighted by their childhoods, but are, instead, equipped to lead full and fulfilling lives. George Eliot evidently felt the same way.

Bibliography

Ashton, Rosemary. "Lunch with the Rector: George Eliot and Mark Pattison Revisited." The Times Literary Supplement. 31 January 2014: 14-15.

Byatt, A. S. Introduction. The Mill on the Floss, by George Eliot. London: Penguin, 1979. 7-40.

Cross, John, ed. George Eliot's Life as Related in Her Letters and Journals. Vol. I. New York: Harper 1885.

Dickens, Charles. Hard Times. London: Penguin, 1994.

Eliot, George. The George Eliot Letters. Ed. Gordon Haight. Vol.3. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954.

_____. Middlemarch. Ed. W. J. Harvey. London: Penguin, 1965.

_____. The Mill on the Floss. Ed. A. S. Byatt. London: Penguin, 1979.

England's Daughters: What is Their Real Work? (London, 1870): 9.

Ermarth, Elizabeth. "Maggie Tulliver's Long Suicide." Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900. Vol. 14, No. 4, Nineteenth Century (Autumn, 1974): 587-601.

Fleishman, Avrom. George Eliot's Intellectual Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Fourth Annual Report of the Poor Law Commissioners for England and Wales (London, 1938): 298.

Golden, Catherine J. Images of the Woman Reader in Victorian British and American Fiction. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2003. See especially Golden's excellent chapter 3, "Prophetic Reading," on Maggie Tulliver.

Haight, Gordon. George Eliot: A Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968.

Hughes, Kathryn. George Eliot: The Last Victorian. New York: Cooper Square Press, 2001.

King, Jeannette. Tragedy in the Victorian Novel: Theory an Practice in the Novels of George Eliot, Thomas Hardy and Henry James. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Meredith, George. The Egoist: An Annotated Text, Backgrounds, Criticism. Ed. Robert M. Adams. New York: Norton, 1979.

Moers, Ellen. Literary Women. London: The Women's Press, 1978.

Sadoff, Dainne F. Monsters of Affection: Dickens, Eliot and Brontë on Fatherhood. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1982.

Tomalin, Claire. Charles Dickens: A Life. London: Viking, 2011.

Yeoh, Paul. "'Saints' Everlasting Rest': The Martyrdom of Maggie Tulliver." Studies in the Novel. Vol. 41, No. 1 (spring 2009): 1-21.

Created 20 February 2014

Last modified 14 February 2024